XFL @ MSNBC.COM: Reflecting on a moment and looking to the future

Fred Mason / University of New Brunswick

Through the winter of 2001, I followed messages posted to MSNBC’s online bulletin board system (BBS) devoted to the XFL. It proved a difficult task due to the volume of traffic, and by the time the league’s only season came and went, I had downloaded over 3000 postings threaded through different topics. I originally planned to assess what sense football fans were making of the hyper-mediated broadcast style of the XFL. A large percentage of posts were concerned with media issues, as fans intelligently discussed many aspects of the overall broadcast package. Some of the further uses of the BBS surprised me, with a group of about 60 participants spending significant amounts of time following discussions that often verged far off the topic of football, into such things as other sports, national politics, family life and personal issues. In the days before Facebook and MySpace, back when we still questioned whether an “online community” was a possibility, I became enamored with the idea that we had a new technology allowing people both to come together, and to discuss and challenge the dominant forms of media and the way it presented things. Since then, social networking is a reality and we often hear of the emancipatory possibilities of Web 2.0. Meanwhile, after further years of teaching and researching the sports media, I’ve become more skeptical of the perspective that new technologies will offer “freedom” to the consumer, especially in regard to sport. Here, I want to look back on the XFL and MSNBC.com’s XFL BBS, with a view to seeing what the relatively recent past might tell us about the future of sport and the media.

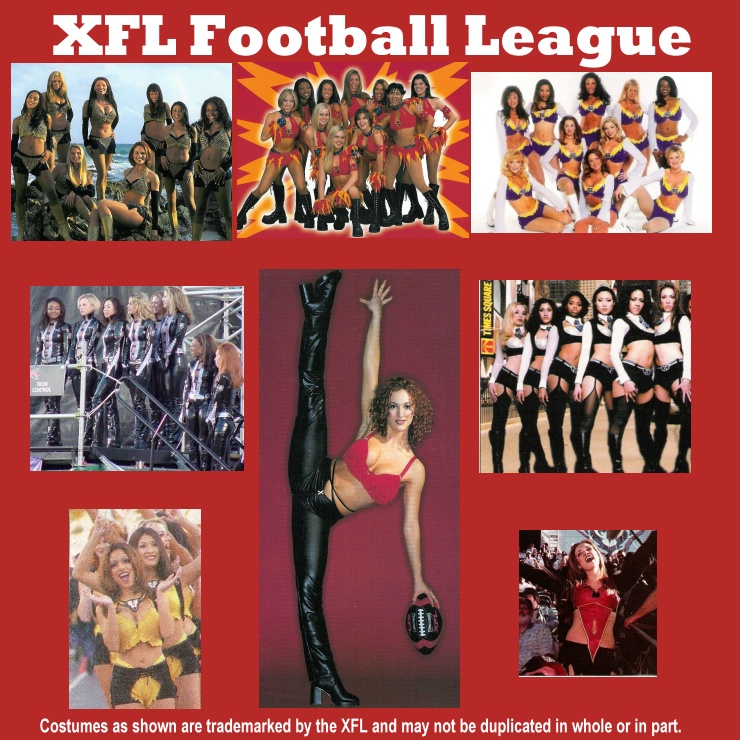

Those who remember the XFL probably remember it as an unabashed combination of sport and entertainment, the brainchild of World Wrestling Entertainment boss Vince McMahon and NBC sports guru Dick Ebersol. Conceived as an alternative league after NBC lost the rights to the NFL in 2001, it was designed to be more “smashmouth,” sexier and more viewer-friendly than what McMahon called the “No-Fun League.” 1 Featuring low-paid, “working-class” players, it attempted to make up for talent with attitude and camera penetration. Rules were changed to make the game more violent and exciting, such as doing away with the fair catch for kick receivers, and having a scramble for first possession of the ball rather than a coin toss. The scantily clad cheerleaders were highlighted more, and wrestling announcers such as Jim Ross and Jesse Ventura (then in his stint as Minnesota governor) called the color. New camera angles such as the overhead “Skycam” were brought in, players, coaches and referees were miked, and for the first time, the broadcast offered an inside view of huddles and locker room pep talks. It essentially took prevalent trends in the media coverage of sports to an extreme, adding in a little WWE showmanship.2

To make a short story shorter, the XFL started with a 9.5 Nielsen rating on its opening broadcast, but dropped to an all-time prime-time low (for programming of any genre) of 1.5 by the end of its regular season, nowhere near the 4.5 NBC had promised advertisers. Their initial curiosity sated, viewers found other things to do on Saturday nights, and the mainstream sports media outlets, perhaps unfairly, never gave it a chance. The league folded shortly after the end of the season, with NBC and WWE each losing a reported $35 million.3

Those who have seriously considered the XFL’s failure (rather than denouncing it from the beginning), argue that the hyper-mediated spectacle was not the primary problem; instead, the football product itself was poor and thus turned fans off, for many by not living up to its own hype.4 Newman, Grainger and Andrews take great pains to point out that the XFL really constituted an extension of the trends typical of sportscasting in the late capitalism era, and that the similarities between the NFL and XFL far outweighed the differences, at least in terms of media spectacle. They argue that to differentiate from the NFL, the XFL possibly needed to accentuate WWE-like production values even more.5 So this is the formula of which the XFL became a logical extreme. But what did consumers (those who continued to care) make of it?

As with any BBS, random users posted ‘flames’ aimed at the XFL and its fans, and others rose to their defense. As with any sport-related BBS, fans engaged in a certain amount of the horrendously named BIRGing (Basking in Reflected Glory) when their teams won.6 However, as noted above, many posters displayed much knowledge about football and its mediatization, with threads discussing the commentary, the camera angles, the “add-on” features and the potential effects of television ratings on advertising and the league’s very survival. Participants discussed at length which of the rule changes added to the spectacle, or served to impact negatively on the “football product.” Many supported the “working-class heroes” of the league, and juxtaposed them against athletes in the NFL and other sports. Throughout the season, a large number of regular BBS users (approximately 100), critically discussed the relationship of football to the media and how this played out practically on their television screens.

There is a huge “BUT” here, though. BBS users could be very critical of the media package presented to them, but no one ever questioned the televised sport manhood formula on which the XFL traded. While they discussed whether the cheerleaders lived up to the hype, they never addressed the XFL’s concept of them being more available and less clad. Similarly, while there was intense discussion of how much the XFL lived up to its “smashmouth” marketing campaign, the tenets of that campaign (violent body contact, hypermasculinity, injury and bodily sacrifice) never, ever, came up. In thousands of posts, no one thought to question the dominant forms of sport and whether they were a good thing.

I find this surprising, because there was a lot of discourse on the XFL’s sleaziness in the mainstream sports press. Many sportswriters, including those with a national audience, reacted negatively to Vince McMahon’s involvement and never gave the XFL a chance. Even Hunter S. Thompson, known to like a good spectacle on occasion, wrote negatively from the beginning in his ESPN.com column. Expressing the wider opinion in his own style, he wrote that, “If the TV ratings start looking weak, the Lewdness level will be the first thing to change – if only because it will be a lot easier to hire naked cheerleaders than go out & find better players…We are stuck with this fraud for a while. But it is a lot better than being in Prison.”7 Perhaps the press discourse did not cross over to XFL supporters, or perhaps they ignored it as being disingenuous coming from writers who regularly promote the same sorts of things in everyday sport, if less overtly. In any case, while the BBS users on MSNBC.com expressed very critical and insightful opinions on the broadcasting of the XFL, they rarely thought, if ever, to question the dominant structures of professional sport, of the “normal” ways of doing things.

Looking back, it frustrates to consider that even with a new form of technology, and a new voice to express themselves with, football fans were not able to break with dominant visions of the sports world and how it should be. Looking forward, I wonder if we won’t continue to see more of the same. While we have good bloggers and participatory journalism of new and interesting forms, I don’t expect mainstream media outlets, with sport particularly, to loosen their stranglehold just yet. Professional, elite level sports have been built around deep relationships with beat reporters and television networks, and it is within their interests, promotionally and financially, to maintain these relationships. As with the XFL BBS, new possibilities and directions will open up, but with professional sports at least, old formulas will still hold a lot of power because there’s just too much at stake.

Fred Mason is an Assistant Professor teaching sport sociology and sport history in the

Faculty of Kinesiology at the University of New Brunswick. His longstanding

sociological interests are in sport and the media, with a focus on gender, disability

and multiculturalism. He is currently working on projects related to media coverage of

disability sport and sport in science fiction.

Image Credits:

1. XFL Logo

2. XFL Cheerleaders

3. Homer Simpson, a true XFL fan?

Please feel free to comment.

- Brett Forrest, Long Bomb: How the XFL Became Television’s Biggest Fiasco, (New York: Crown), 2002: 13-15 [↩]

- Joshua I .Newman, Andrew D. Grainger and David L. Andrews, “Even Better than the Real Thing? The XFL and Football’s Future Imperfect,” Football Studies, 6.2 (2003): 7-8, 17-18. [↩]

- Forrest, 51, 211, 219-220. [↩]

- For example: Keith A. Willoughby and Chad Mancini, “The Inaugural (and Only) Season of the Xtreme Football League: A Case Study in Sports Entertainment,” International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, (Sept-Oct. 2003), 227-235. [↩]

- Newman, Grainger and Andrews, 16-17.)

One of the clearest enunciations of the dominant pattern of televised sports coverage calls it the “televised sports manhood formula.” Conducting a textual analysis across a range of sports programs on different networks, the authors drew out a number of themes, including sport’s representation as a man’s world with women as objects for consumption, and a celebration of aggressiveness, violence and sacrifice of the body. They note that the formula provides a “stable and concrete view of masculinity as grounded in bravery, risk taking, violence, bodily strength and heterosexuality.” ((Michael A. Messner, Michele Dunbar and Darnell Hunt, “The Televised Sports Manhood Formula,” Journal of Sport & Social Issues, 24 (2000): 392. [↩]

- Christian M. End, “An Examination of NFL Fans’ Computer Mediated BIRGing,” Journal of Sport Behavior, 24 (2001), 168-173. [↩]

- Hunter S. Thompson, “Lynching in Denver,” ESPN.com (Feb. 5, 2001). Reprinted in Hey Rube: Blood Sport, the Bush Doctrine, and the Downward Spiral of Dumbness (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004): 38-40. [↩]