Pow! Ooomph! Skadoosh!: Combat Aesthetics and Intermediality

Matthew Ferrari / University of Massachusetts-Amherst

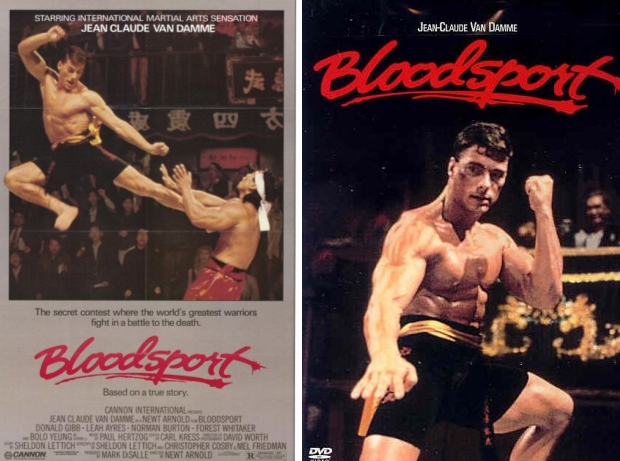

A few years ago I somewhat sheepishly confessed to one of my professors that I wanted to write about mixed martial arts (MMA) media. This apparently required some clarification because he asked what I meant exactly. “You know, The Ultimate Fighting Championship.” “Oh, that,” he replied. “…It’s like all those Jean-Claude Van Damme movies from the 80’s came to life.” At home my partner’s uptake was perhaps less savvy to these cinematic antecedents. Once, during the first weeks of my regular MMA viewing, she accidentally (or mockingly) called it “extreme wrestling.” Upon reflection, though, the theatrics of MMA events do share a likeness to professional “wrestling’s” carnivalesque excess. For months she readily accepted that I was watching it as “research” into taboo (by our standards at least) cultural exotica overlapping with some of my existing theoretical and thematic interests; and generally that it hailed me – simultaneously repelled and attracted me to be more precise. But key to the rhetorical strategy of such “reality” programming is to take you beyond surfaces by cultivating a formal literacy and technical proficiency, so you can perform as “critic”/commentator alongside those in the show. Before I knew it I was enthusiastically calling said partner into the living room to behold this improbable “kimura,” or that spectacularly timed “flying knee.” (To no avail; it never quite took with her). What I get now is a rather fatigued, “are you done watching people beat themselves up yet?” Well, as it just so happens, I’ve been watching “people” spectacularly beat themselves up since the 1980’s within the fictions of film and video games. Why now, with its ascendancy to full-fledged “actuality,” should I feel depraved for taking pleasure in it?

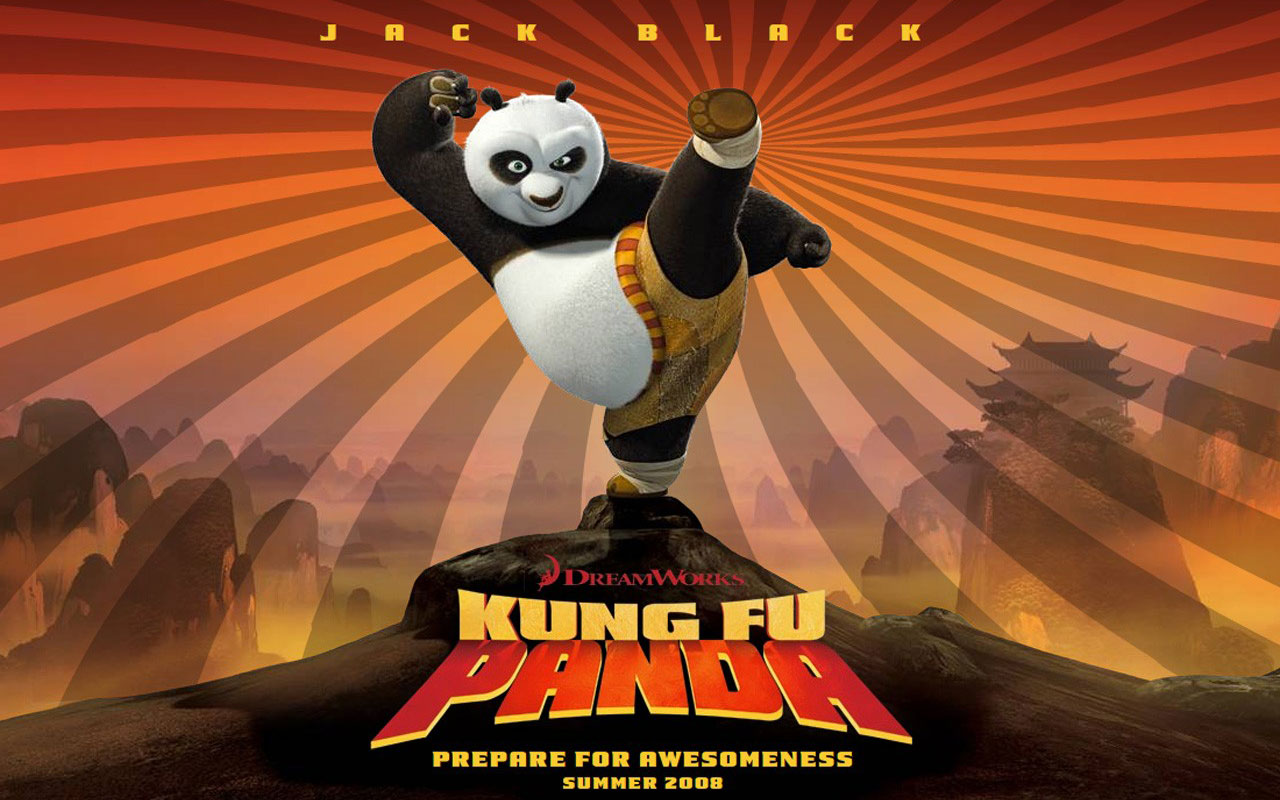

Recent work in genre theory by Paul Young considers the importance of considering genre in terms of “intermediality.” This is similar to the poststructuralist idea of “intertextual relay,” in which generic “horizons of expectations” are established in the audience’s mind even before the text arrives.1 Young maintains video game studies (“ludologists”) would greatly benefit from applying the concepts of film genre theorists to their objects of study (and vice versa for genre theorists). He discusses how video game designers have appropriated cinematic narrative conventions for use in video games.2 These circuits and cycles between media occur in multiple directions. My argument here is that the sale and promotion of the mediatized combat aesthetics of MMA benefit profoundly from existing generic regimes established in movies, video games, and comics. As I was gradually persuaded of the possibility for some “art” in mixed martial arts, the legitimate techné through which this prowess was channeled (in the best examples at least), I also grew more sensitive to the promiscuity of combat aesthetics and combat “play” across various media forms. These forms have sewn the seeds of a kinesthetic-aesthetic literacy for the vast appreciation of mediatized combat. These are aesthetics of power and domination, of blunt force trauma, of the “anaconda choke,” the “superman” punch, the prowess and potential of the body’s mundane instruments –hands, arms, legs. “Submitted by rear naked choke in the third round!” “Pow! Ooomph! Zowie!” as the old Batman program had it. Or, “Skadoosh!” as Jack Black’s Kung Fu Panda (2008) puts it.

The pleasures and continually evolving repertoire of combat aesthetics are deluged on us from the seemingly cuddly, childhood narrative product (foisting violent action “play” on children through anthropomorphized animals and moralizing narratives), through to the brutal and fearsome “gladiatorial” warriors of football, and now, in even more enhanced and explicit ways, MMA. Combat aesthetics –in their perpetual replay and fetishistic visual scrubbing and digital intensification– are fundamental to the sale and promotion of MMA product and programming, with a ready-made regime of cultivation materials in animation, action and martial arts cinema and video games. I have little doubt that my hailing by MMA combat media has roots in the tens (or hundreds?) of hours I spent as a kid (at friends’ houses only though! No electronic game consoles in my household) playing violent video games (and to be precise, they were: Street Fighter 2, Battle Arena Toshinden, Mike Tyson’s Punch Out, and Ninja Gaiden – how could I forget), not to mention all of the football and action films.

Media studies scholars are justifiably wary of direct transmission models of viewer/consumer behavioral responses to media exposure, careful to allow room for “negotiated” and even “oppositional” readings/responses to hegemonic cultural encodings.3 But mimetic play is a powerful force, especially among youth. Some anecdotal evidence: my four and seven year olds were utterly lost to imaginary Kung Fu fighting for days after they saw Kung Fu Panda. And for a less cuddly example, a recent New York Times article reported MMA making forays into a Massachusetts high school.4 Local martial arts schools once devoted to singular traditions are giving way to MMA programs conforming to the mixed combat aesthetic exploding on the small screen. (The most recent “explosion” was the September 16th premiere of season 10 of The Ultimate Fighter, which was the most watched cable program in its time slot with 4.1 million viewers. Completing the cycle from fictional media, to “real” (i.e. MMA), back to fictional, is the arrival of UFC Undisputed – the video game. I’ve never played it, but the website claims the game has replicated an “authentic and comprehensive UFC atmosphere.”

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cBlfLxolRIs[/youtube]

The promotional video for upcoming UFC 104: Machida vs. Shogun contains new levels of digital augmentation and intensification in its highlight reel format, exhibiting a close visual affinity with video games and animation. Strikes (i.e. kicks, punches, elbow and knee strikes, etc.) are laced with popping sparks, and sweeping trails of white energy follow in their path. I’m transported back to my earlier days of puerile rapture with combat games like Street Fighter II and Battle Arena Toshinden (and the more recent ones I’m surely missing out on) where fighters can manifest blasts of pure energy against their opponents. But for the “adult” viewers of MMA, there are more tasteful nods to the “art” of combat. Take Tapout’s most recent commercial depicting the “flying armbar,” in all of its acrobatic glory, with the aid of slow motion, dramatic low-key mood lighting, and a romantic classical violin score.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NS6HcWSE7-M[/youtube]

Mediatized combat aesthetics are, to my mind, part and parcel of the dominant generic regime of masculine melodrama. Linda Williams explains that female melodrama has historically involved tears and excessive affect (the “weepie,” one of the “gross body genres”, along with porn and horror), while (I contend) masculine melodrama involves blood, sweat, and combat’s agonistic aggression.5 My own “submission” to the pleasure of MMA melodramas reminded me of the promiscuity and entrenched state of these aesthetic regimes. The seemingly innocuous act of letting our 4 and 7 year old boys watch Kung Fu Panda is, in all likelihood, the start of a much longer, and potentially dangerous, love affair.

Image Credits

1. Digital Augmentation in Video Games and UFC (author screenshot)

2. Mixed Martial Arts: “Jean-Claude Van Damme movies come to life”

3. Combat Aesthetics in TV’s Live Action Batman

4. Kung Fu Panda: Starting a Potentially Dangerous Love Affair

5. UFC 104 Preview

6. Tapout Commercial: Arm Bar as High Art

Please feel free to comment.

- The “horizon of expectations” is a well known concept in genre theory and criticism expressed originally by Hans-Robert Jauss. [↩]

- Young, Paul. 2008. “Film Genre Theory and Contemporary Media: Description, Interpretation, Intermediality.” In The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [↩]

- Hall, Stuart. 2006. “Encoding/Decoding.” Media and Cultural Studies: Key Works. Eds. Durham and Kellner. Malden, MA: Blackwell. [↩]

- Porter, Justin. “Mixed Martial Arts Makes its Way To High School.” The New York Times. November 17, 2008. [↩]

- Willams, Linda. 2004. “Film Bodies: Gender, Genre, and Excess.” In Film Theory and Criticism: Introductory Readings. Eds. Leo Braudy & Marshall Cohen. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [↩]

Thanks for a very interesting column, Matt. I really like how in this column you’ve moved outward from more immediate interests specifically in mixed martial arts and look at where else this discourses and aesthetics occur and how else they work to appeal to diverse audiences across time and place.

Thanks, Mabel. This comes from wanting to interrogate more my own subjective pleasures in MMA, and the challenge of separating that pleasure from all of these other media sites where a reverie for combat is implanted. I’m also troubled by how so many kids films are essentially action films with more explicitly moralizing narratives. Kung Fu Panda had my kids fake fighting, but the “fake” part becomes very tenuous when they enact/perform without inhibition, self-control, discipline, etc. as young kids are wont to do. (It’s like when dogs “playing” crosses that thin threshold to become dogs fighting). I have to say also that I would like to know more about female mma viewership and how their pleasures might be very different. Thanks for commenting. -Matt

This is a pertinent topic which over the coming years will only become more charged and convoluted. Further, the points discussed are brought about in a clear and near irrefutable manner.

However, the last charge of censorship with youths is of course a sensitive (and debatable) one. Should a child be sheltered from something for a period that might be construed as too long, then they are at risk of reacting to it in more extreme ways than should they have been exposed originally and allowed to interact with the material themselves and then educated and so forth. The contentions about male melodrama all address the dominant North-American male perspective, though the ways in which they transfer their beliefs to the coming generations is a complex one and cannot necessarily be contained by total protection.

Thanks for the comment, Jesse. Just to be clear, though, I am absolutely not advocating a censorship position (and don’t believe this is implied in the column), but rather simply calling attention to, and at most submitting a warning about, how these aesthetic regimes of violence are implanted at a very young age, often through apparently innocuous media (like Kung Fu Panda), which we would do well to at least recognize in the media diets of our youth. I’m not quite sure what you mean by “total protection,” but I’ll assume this is also about censorship. Above all my project here is to start tracing formal relationships across media that might not ordinarily be discussed in the same context, not to argue for content that needs to be censored. (after all, I let my kids watch it). In continuing the lines of this kind of comparative media analysis, a positive direction would be to start naming alternative youth media that avoids action-sensation and combat centered narratives. Suggestions? In general though, there has been very little discussion of why MMA (and of course the UFC in particular) is growing so rapidly. One starting point (the one I make here) is to consider MMA media’s combat focus as part of a broader constellation of related aesthetic forms situated across media, history, and audience demographics. -Matt