Performing Live: Acting, Authenticity, and Reality Television

Adrienne McLean / University of Texas – Dallas

This column is a rumination on some of the people we watch on reality television. It was prompted by several months of addiction to BBC-America’s Cash in the Attic, as well as by HGTV’s evening lineup in which more or less horrifying things are done to folks’ homes in the name of “updating” or “improving” (more on house porn next time).1 Of interest to me are shifts in the meaning of what is often referred to as TV’s “ontology of liveness,” in particular how liveness and reality and authenticity seem to have become virtually synonymous concepts on commercial entertainment television.

Anecdote 1: In the 2007 HBO series Tell Me You Love Me, which concerns a group of loosely connected couples with relationship issues, a wife poses the following question to her spouse, who is fiddling with his TiVo to avoid talking to her: “‘Are you ever going to watch live TV again?” He answers, “Not if I can help it.”

Anecdote 2: In November 2007, Entertainment Weekly featured the following letter in response to an article about changing television demographics and how they are measured: “The Nielsen ratings are antiquated and inaccurate. I don’t know anyone who watches live TV anymore: We’re using our DVRs or our computers. If the networks are listening to Nielsen, they should be airing The Ed Sullivan Show.”

Anecdote 3: This spring, I overheard a guy discussing how he had watched something “live” on his “smartphone.” He was referring to a popular YouTube video, not an event to which he had immediate access as it was occurring in the world.

What these anecdotes suggest to me is that the meaning of “live” has been substantially disconnected from its association with the immediate (re)presentation or broadcast of an event to the site and time of that event’s consumption, and I am fascinated by how this all interacts with what I have come to think of as reality-TV “acting.” In Cash in the Attic, as with endless other shows of this ilk, an emcee (the “host”) appears first, his job (in older episodes it’s a woman) being to explain where we are and why. However casual his manner, the host is an obvious show-business professional, and he addresses his performance directly to the camera. This also invokes liveness, though, in that as a style of performance it mimics that of the roving on-location newsperson, about to report on something that has not yet occurred—here, the visit to a household by one of two antiques experts who will rummage through the family’s stuff looking for things to sell at auction (an auction we will also attend and that will generate the suspense of whether the family will or will not make a certain sum of money). Once the expert arrives, everyone—host included—now studiously avoids looking at the camera, acting, in all senses of the term, as though the camera is not there, as though what is going on is simply being recorded as it happens. Moreover, the non-actors, in contrast to the host or even the expert, perform with what Robert Self refers to as “the ring of the amateur.”2 They are acting as themselves, but they aren’t very good at it—they’re usually a bit stiff, and if they try to be “lively” and “natural” it’s even worse. But it is important that there be “bad acting” in reality television by people who are not actors by trade, because that makes the people therefore real, believable; the “ring of the amateur” is itself the mark of the authentic.

It is not that “true” liveness has ever been common on commercial television; but as Jane Feuer pointed out long ago, whether something actually is live is not as crucial as the “impression of liveness” manufactured by television and its techniques and production values.3 Feuer claims that “as television in fact becomes less and less a ‘live’ transmission, the medium in its own practices seems to insist more and more upon an ideology of the live, the immediate, the direct, the spontaneous, the real.”4 Justin Lewis goes so far as to suggest that reality television, whether makeover show or the “more fanciful world of gamedoc captivity,” depends upon “the idea that we are watching real people in all their unscripted vulnerability.” 5 It is not too far from this to suggest that real people are the marker of the live and, or as, the unscripted.

Given that actual liveness is so rare, except in the case of news and the “breaking story” (including the grand finales of some competition-based reality shows), I think I’m suggesting that the value of liveness as the ontological characteristic of the televisual has been supplanted by, and is often confused with, what is proffered as “reality.” Reality is “what was once live” (rather than rehearsed and acted) and has come to be located more and more in modes of human performance (and spectatorship) even as other formal mechanisms of reality programming (camerawork and cinematography, editing, sound) take on all of the characteristics of “classical” film- and television-based storytelling. Authenticity and liveness have also become essentially interchangeable attributes, such that the “ring of the amateur” means authenticity, and authenticity in turn means liveness—the unscripted, the unrehearsed, the accidental (even when clearly things are rehearsed, are scripted, are not accidental). The complex interaction of notions of liveness, authenticity, and reality can of course be explored using any range of television texts, but I believe that “performing real” on television and in other digital technologies retains an association with “performing live,” an intersection that film, despite its long history of actualities, documentaries, and other modes of reality-based cinema (or, conversely, the consumption of film as television, through the burgeoning home-theater market, or as downloadable Internet content), does not yet share.6

Perhaps this explains why so many (mostly younger?) people call scheduled television programming “live,” because it is in opposition to that which they choose to watch on their own time in a particular place (and a “smartphone” makes things live because they can be accessed anywhere). And while this liveness might be fake on certain obvious levels, it exists, or it matters, because we want to believe that somewhere there is liveness in which we might choose to partake but which we don’t have to watch as it happens. In other words, the ultimate paradox, for me, is that reality television may work in this moment partly because real live television is much, much too scary, too unpredictable, too disturbing.

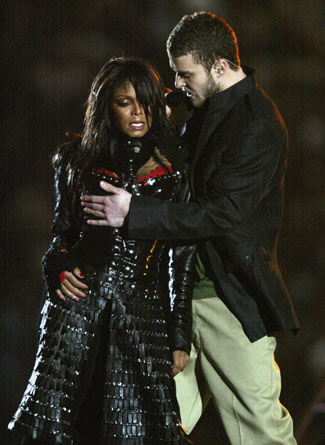

It’s not hard to notice that the attempts to make reality programming seem live and immediate are also ultimately protective—we are never going to see anything that’s out-of-control live (much less true “dead time”), the way live “used to be.” Reality TV and its acting styles now substitute for and are read as the live, perhaps in some melancholy or earnest or deluded attempt to keep the real live world where it safely belongs—someplace where we can control it, or where we can sooth ourselves that it all comes down to voting with our cell phones for whom we think deserves to win Dancing with the Stars.7 It’s much too horrible when what looks like a movie turns out to be real, and live, and immediate; much better, much easier, that what looks real, and live, and immediate, turns out to be just entertainment.

Image Credits:

1.) The Hosts of BBC’s Cash in the Attic

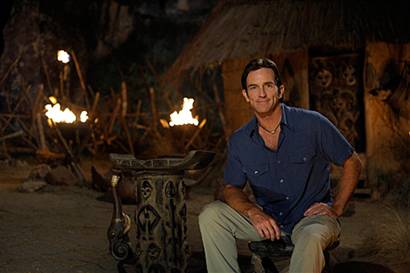

2.) Survivor host Jeff Probst Evoking Liveness

3.) Live Television at its Scariest, Most Unpredictable…

Please feel free to comment.

- There’s an HGTV version of Cash in the Attic too, to which all these comments pertain, but I find its “attics” much too boring. [↩]

- Robert T. Self, “Resisting Reality: Acting by Design in Robert Altman’s Nashville,” in Cynthia Baron, Diane Carson, and Frank P. Tomasulo, eds., More Than a Method: Trends and Traditions in Contemporary Film Performance (Detroit, Mich.: Wayne State University Press, 2004), 142. [↩]

- Quoted in Rhona J. Berenstein, “Acting Live: TV Performance, Intimacy, and Immediacy (1945-1955),” in James Friedman, ed., Reality Squared: Televisual Discourse on the Real (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2002), 27. [↩]

- ibid [↩]

- Justin Lewis, “The Meaning of Real Life,” in Susan Murray and Laurie Ouellette, eds., Reality TV: Remaking Television Culture (New York: NYU Press, 2004), 288. [↩]

- As Arild Fetveit puts it in “Reality TV in the Digital Era: A Paradox in Visual Culture?,” the “simultaneity of the digital ‘revolution in photography’ and the proliferation of visual evidence seems paradoxical. It seems as if we are experiencing a strengthening and a weakening of the credibility of photographic discourses at the same time” (in Friedman, 119). [↩]

- To me, this seems borne out by the increasing significance of the Internet and its user-driven content—see recent coverage of events in Iran, among many possible examples—as the locus of “the live” as well. [↩]

Now you play dvd on windows 10 online without having any problem.