The Making of My Mothering Movie: Birthright

Becoming a mother shocked my sense of self as a social being. Having given birth to two children before tenure, six years later I still crave sleep. Before the birth of my first son, I did not expect the daily minute-by-minute joy and beauty, the painful attachment, the difficulty of returning to work, and the powerful desire to stay home. Devote myself completely to childrearing? Guilt—a slow ever-present, torturous companion to my new life—accompanied this consideration. I finish my book, get tenure, teach and mentor, contribute to faculty governance, travel and through every sleepless night, work as if it was my last contribution to the world. In the mirror, the bags under my eyes shout the astounding need to sleep. After the birth of my second child and the difficult recovery that required six weeks of bed rest, I never asked for medical leave. The pressures to produce work and the pressures to care for myself and my family conflict, creating what Gail Weiss calls the conundrum of the mother-intellectual who can’t be “and” or “both,” but only “neither” and “nor.”1

I started reading up on mothering—to find a language, learn from others, and create a work—to name the experience and disseminate new knowledge so as to help capture not only my own concerns but to expose others. I learned that the pressure I experience is what Sharon Hays calls the conflicted “ideology of intensive mothering,” and that most women feel it, regardless of their economic situation, their culture or ethnicity, and even whether they work or not.2 It’s that simultaneous pull women feel: that the proper care work responsibilities belong to them. Can one be a good mother and a good worker? Is that an impossible dream that requires not only family but funding, community, fair and humane laws and gender equality?

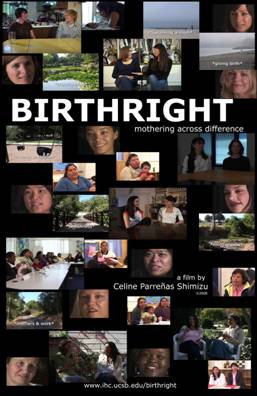

The result of this quest: Birthright: Mothering across Difference. Through interviews with approximately 50 mothers in the Santa Barbara area, my experimental ethnographic film offers a multi-class and multi-racial account of mothering. Santa Barbara epitomizes the stratified society of the United States, where the extremely rich and extremely poor live side-by-side in the “new economy.” In the context of this disparity, how is mothering experienced?

What I find is that within the incongruent economies and racial divisions in Santa Barbara, communities and friendships form across the dynamics of race, class, gender, and sexuality. All of the interviews involve the critical act of talking in ways that challenge the private/public divide in order to address the ways in which women of various communities face challenges and negotiate neoliberalism today. I discover that neoliberalism, with its resulting stratified labor market and policy of privatization, leads us to form different types of alliances and forces us to revisit the racialized, gendered, classed, and sexualized experiences of mothering. We see a wealthy woman speak immediately after a poor woman and we hear a diversity of racial and ethnic experiences—and in opening their lives to each other and to us, connections are made.

A working class woman tells me she feels no guilt with working, knowing her kids will be proud of her for attempting to juggle it all. From a wealthy woman, I learned about feeling the “pressure of not working” and that they are “not quite cutting it because they are not juggling it all,” even as they meet the idealized version of who should care for kids. One woman, a former VP of a bank, assessed that women are lying when they say they have it all: “as workers, we must suppress so much of ourselves, as stay-at-home women we must suppress so much of ourselves.”3 A poor woman celebrates her ability to endure and get through another day.

Mothering is a site where women are disciplined and identities are formed. It offers the opportunity for forging new friendships as well as for subjugating others who don’t fall under normal categories of good motherhood. In it, we can witness the pressures women face to mother in a certain way. We also see the incredible challenge of work and life issues that women wrestle with painfully. Mothering is a tremendous challenge to one’s identity in a capitalist, neoliberal society where the self and the individual are privileged. The film shows how mothers live in difference and mother differently, while also sharing certain commitments. In this way, I seek to illuminate the challenges all mothers share without eliminating their differences. I conclude with the powerful way women forge alliances and connections as they become mothers. These new bonds help them survive the everyday demands that consume women’s lives as well as fuel them with incomparable joy.

As we live in the moment where mothering is celebrated and idealized in popular culture, my film intervenes with a more complete story of the joy and pain of becoming a mother. I look at a variety of specific groups of women who organize under shared interests: organic lifestyles, queer families, multicultural/national families, Spanish-speakers, or Family Literacy. By collaborating with three local non-profit organizations devoted to supporting mothers, I wanted to capture the ways in which communities are formed as well as fortified when encountering difference during the intense years of early childrearing.

From our intense hope that we are making the right choices, the questions we need to ask are not only what are women doing to mother well, but what is society doing? How do we cope with institutional mechanisms that attempt to address the needs of women but often privilege men? What are institutions doing to help with birthing and child-rearing, and to help different women get through these important times in life?

A year and a half of reading and pre-production, half a year of shooting, and a year and a half of post-production—nearly four years of intellectual pregnancy, and finally the film is born. It premieres at the Reelheart Film Festival in Toronto, Canada on June 24, 2009 and is available for distribution from www.progressivefilms.org for institutions and individuals. Recently, one of the women in the film told me she’s pregnant again. For her, I feel a surge of happiness, fear and hope. I am reminded of the life and death involved in giving birth, what my informant calls the true meaning of beauty and the sublime: the power of bringing oneself to the edge of existence and the commingling of terrible pain and happiness.

Today, my children are less dependent on me. They ask me to go away and do my own work as they build Lego cities. I realize that I myself am finished with birthing and a tremendous sadness fills me. I realize not only my own mortality but the incredible generosity required in mothering work, for which I have limits. Mothering makes me more aware than ever of how media has the power to express these experiences and shed new light on communities that people think they already know. I hope playgrounds and stroller brigades become more recognized in our society as sites and events where women struggle to make sense of our lives, the losses and the gains, and our hopes that we are choosing and doing right for and beyond ourselves.

Image Credits: All images provided by the author.

Please feel free to comment.

- Weiss, Gail. Refiguring the Ordinary. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, c2008. pp 199-201. [↩]

- Hays, Sharon. The Cultural Contradictions of Motherhood. New Haven, [Conn.]: Yale University Press, c1996. p 173. [↩]

- Birthright: Mothering Across Difference. Dir. Celine P. Shimizu. DVD. Progressive Films, 2009. [↩]

This is fascinating!

I am especially interested in the idea that women experience motherhood– and the pressures of motherhood– similarly across ethnic and economic borders, because that is not obvious in scholarship today. The way women mother, and the choices that women make when determining whether or not to be working mothers, seems highly culturally prescribed in much of the literature out there. I feel like the trend is to pinpoint how women experience motherhood differently based on these socio-economic factors, in order to resist upholding any one dominant idea as “common experience.” But there is still beauty in expressing commonality through difference, especially when looking at how external factors shape the ways women imagine ideal motherhood.

I look forward to seeing your film!

All the best,

Laura

Thanks for your comment, Laura. This was an unexpected finding for me to identify the shared gendered constraints these mothers experienced—while recognizing inequality and difference. I asked the diversity of women the same questions about their intentions to become mothers, how they imagined becoming or living as a mom versus the reality, intimate relations with partners, work, family… and with the help of my research assistants identified the best answers–the most surprising, precise, truthful and revealing. Each response showed differences in privilege and power—between wealthy/poor/working moms, differently racialized women, working/nonworking/part time moms. When juxtaposed against each other in editing, these women clearly experienced different kinds of penalties and punishments that revealed the strength of gendered pressures–the specter of the ideal mother that informs their intimate mothering and their identities as mothers. What is striking to me ultimately in the making of the film is the importance of not making judgments about each other—which is a major groundrule of several of the mothering groups to which many of the interviewees belong–and this informed my filmmaking as well. I hope the film invites viewers to listen and hear these women attempt to reach other—and us— with analysis that comes from the frontlines of mothering as socially important acts and identities.