Shooting for Fame: The (Anti-) Social Media of a YouTube Killer

Michael Serazio / University of Pennsylvania

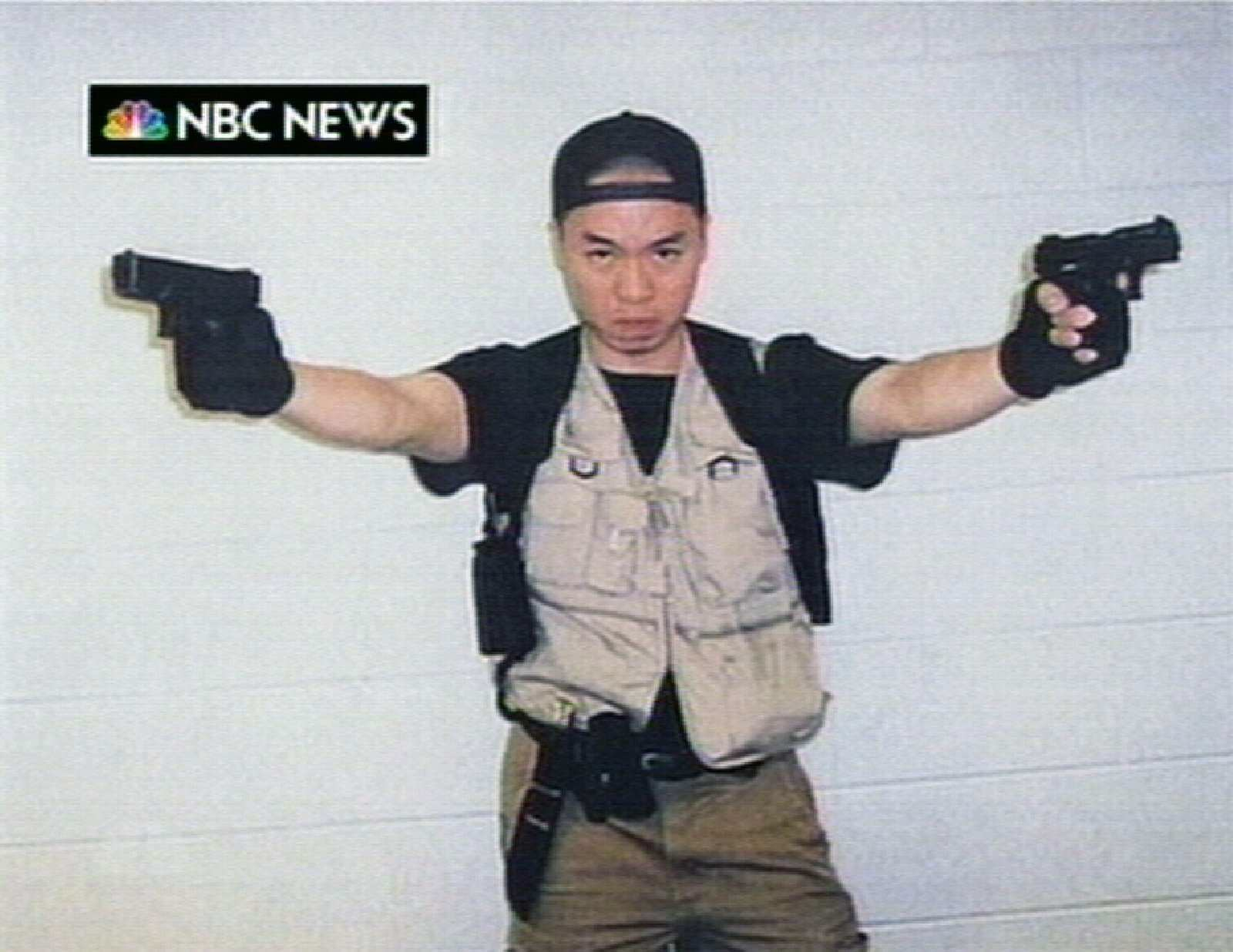

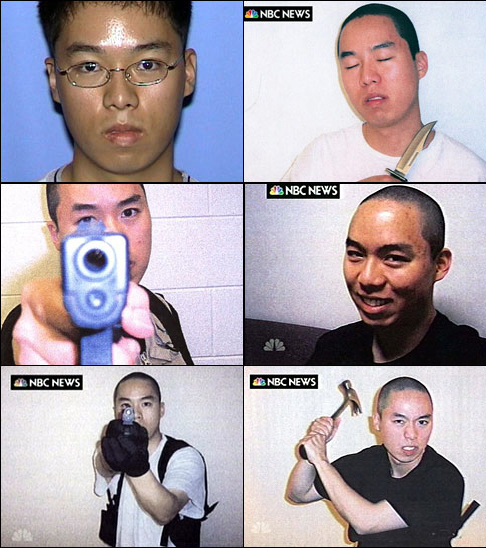

On the morning of November 7, 2007, a shy high school senior named Pekka-Eric Auvinen logged online and called his shots. Executing plans some eight months in the making, the 18-year-old Finnish student uploaded to his “Sturmgeist89” YouTube channel a sinister mash-up titled, “Jokela High School Massacre.” A slow-fade of his lakeside high school interrupted by crimson-tinted poses with him menacing a gun at the camera, and sound-tracked to throbbing industrial rock (KMFDM’s “Stray Bullet”), the posting served as postmodern communiqué: a DIY declaration of the bloodletting Auvinen would unleash just hours later, killing nine (including himself), unnerving Finnish society, and perhaps inaugurating the dystopian potential of (anti-)social media.

There is something tragically familiar about Auvinen’s act that recalls other school shootings of the past decade, yet there is also something disturbingly new given the networked media ecology of contemporary youth. At a juncture when digital technologies and cultural conditions are destabilizing the media landscape and giving way to a kind of celebrity anarchy, such violence is not only premeditated (planned in advance), but pre-mediated as well (that is, packaged in advance). Whether or not “old media” gatekeepers choose to run with the user-generated information subsidy may quickly become irrelevant. In Web 2.0 biosphere, we are all broadcasters and we are all witnesses.

In a way, that’s an odd turnabout. When school shooters kill, the media – both singular and plural – is/are traditionally taken to task, as well as the subculture(s) fostered. A succession of targets over the years – most notably, circa-Columbine, Marilyn Manson, The Matrix and Doom – has been scourged by pundits to shoulder the blame for these recurring nightmares. Yet even the existence – or lack thereof – of demonstrable evidence about media effects on youth shooters misses an emergent point: The question increasingly may be as much what youth shooters do to, with and through media as much as what media do to youth shooters.1

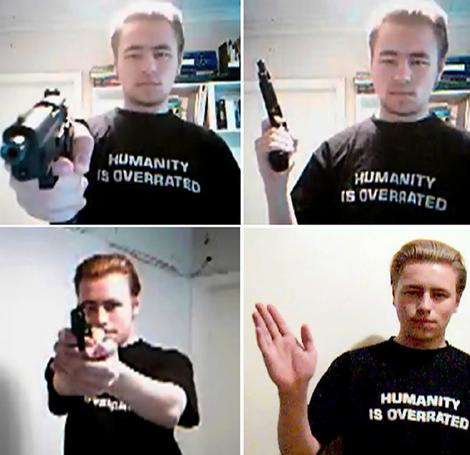

Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold’s home videotapes, Seung-Hui Cho’s NBC multimedia package, and, most emblematically, Pekka-Eric Auvinen’s online portfolio signal narcissistic, notorious youth armed as much with the participatory media of convergence culture as with the firearms they used to author their calamities.2 As Lance Strate points out on his blog, “Guns and cameras are both methods by which people communicate, sending messages to their target and to bystanders alike.”3 The dizzying convergence of producer and consumer roles vis-à-vis social media content as the digital generation comes of age has introduced a new scale, pace or pattern in human affairs and troubled youth like Auvinen develop their “sense ratios” within this technological context.4 In an era when some argue fame is more fragmented and egalitarian than ever before, (anti-)social media lends a frightening pulpit to those who would seek infamy.

It is hard to argue that these young men were not, in large part, shooting for fame with their ghastly actions. A century of mass media accumulation has made fame the dominant currency of postmodern social capital. It has accelerated, if not created, a cult of worship, a “national obsession” – that pervasive and inveterate desire for personal celebrity that shows up embarrassingly on reality TV, gauchely in one’s thousands of MySpace “friends,” and gruesomely in the bodies of work by those like Auvinen (who created before destroying). Yet social media introduces deep volatility into fame as currency in a way prefigured by Leo Braudy: “As each new medium of fame appears, the human image it conveys is intensified and the number of individuals celebrated expands.”5 Before television, this was the vague, distant seduction of film fame; after television, it suddenly appeared open to all; and with the dawn of the Internet era (that Auvinen exploited so fiendishly), those studio walls have been fully knocked down commencing a hyper-mobility of images and avatars. Yet the technologies that empower the Web 2.0 “produser” are the same advances that cheapen the classical definition of fame and its existential appeal: singularity, ubiquity, permanence. It’s hard to stand out in a crowd-source: Here comes everybody, which ultimately makes “You” – Time’s 2006 “amateur-revolutionary” Person of the Year – still a nobody.

To that end, Auvinen’s manifesto (posted to a Finnish social networking site) reads like a Frankfurt School temper tantrum: “Collective deindividualization is a phenomenon where the individual will be trained as part of the mindless herd… It is just done so that people will think they are free and don’t realize they are being enslaved… But not me! I am self-aware and realize what is going on in society!… You can say I have a ‘god complex’, sure… then you have a ‘group complex’! Compared to you retarded masses, I am actually godlike.”6

For Auvinen, the solution to that alienation is found in the spectacle of infamy – now, virally transmitted as (anti-)social media and desperately spotlighting the “me” in meme. This nexus of savagery and celebrity, of course, stretches back decades to Lee Harvey Oswald, the Zodiac killer and Son of Sam. But the new media of the digital era ushers in a user-generated revolution that frighteningly augments the potential to narrate tragedy. The means are there to self-publish as a celebrity killer; only the ends are needed. Because of this, preparation for the act is documented obsessively for posterity.

Again, Auvinen was not the first in this regard. Klebold and Harris had homemade videotapes that showed them fantasizing about their posthumous portrait: “’Directors will be fighting over this story,’ Klebold said – and the boys chewed over which director could be trusted with the script: Steven Spielberg or Quentin Tarantino.”7 In the midst of his own grisly rampage in April 2007, Seung-Hui Cho sent NBC News an 1,800 word manifesto, 43 photographs, and 25 minutes of videotape. In earlier media eras, the celebrity-seeking youth shooter had professional gatekeepers in the way; that Cho, in 2007, pre-mediated by sending NBC a P.R. kit seemed technologically anachronistic. Today’s youth terrorist can, through an (anti-)social media web, be “producer, director, star” and, now, distributor as well.8 It is for this reason that Auvinen became known as the first “YouTube” killer: He demonstrates a disturbing devolution of the mash-up ethos; his cyber-evidence bespeaks the dark potential of Web 2.0. If Cho’s egomania – fertilized by the current climate of technology and celebrity – meant mailing a packaged narrative to NBC, Auvinen knew that he could land on countless screens without needing a broadcast network intermediary. His online presence was prolific; he wrote in English rather than Finnish to maximize his audience; and his home computer contained mash-ups (many of which made their way online) omnivorous in texture: pastiches of Auvinen himself, Hitman video game footage, a Discovery Channel docudrama on Columbine and, taking the viewer fully through the Baudrillardian looking-glass, a remix of Natural Born Killers. But immortality is born of inspiring copycats and, appallingly, Auvinen’s YouTube horror was not the last visited upon Finland. Less than a year later, a 22-year-old vocational student announced, via video, on a social networking site, “You will die next.” Days later, he killed ten.

Much of the rhetoric surrounding social media springs from a hopeful archetype, probably rightly so. Auvinen may well be one in a million (existentially, that seemed to be his grudge). Nonetheless, his despicable handiwork betrays a grim alternative for these networked tools and the flattened hierarchy of media for “Generation Mash-Up”.9 The ever-increasing supply of amateur content populating the Web means that when the next school shooting does arrive, there is a fairly decent chance that journalists – and all online audiences, really – will find a cyberspace trail of hyperlinked, hybridized, media-saturated presentations of the self: narcissism unhinged. If the youth killer’s diary was once only open to reporters at the crime scene, the youth killer’s blog or newsfeed is a much more open book. To narrow the blame to specific media texts that “caused” the killer might be missing the forest for the trees when those texts themselves are poached and scrambled and reconstructed with savage bricolage. When it comes to (anti-)social media, the shooting starts well before the killing begins.

Michael Serazio is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg School for Communication whose research interests include popular culture, journalism, new media and religious media. He has work appearing or forthcoming in Critical Studies in Media Communication, Popular Music & Society, Journal of Media & Religion and Journal of Popular Culture. He also works as a journalist and filmmaker and his dissertation examines the rise of guerrilla advertising. His website is michaelserazio.googlepages.com.

Image Credits:

1. Pekka-Eric Auvinen from his YouTube video “Jokela High School Massacre”

2. Seung-Hui Cho in the Video Sent to NBC before the Virginia Tech Shooting

3. Pekka-Eric Auvinen

4. Pre-Meditated and Pre-Mediated

Please feel free to comment.

- This rephrases Elihu Katz’s discipline-synthesizing framework: Katz, Elihu. “Media Effects” International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences. Eds. Neil J. Smesler and Paul B. Bates. Oxford: Elsevier Science, 2001. 9472-9. [↩]

- Jenkins, Henry. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: NYU Press, 2006. [↩]

- Strate, Lance. “Guns and Cameras.” Lance Strate’s Blog Time Passing. 20 Apr. 2007 http://lancestrate.blogspot.com/2007/04/guns-and-cameras.html [↩]

- McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1964. [↩]

- Braudy, Leo. The Frenzy of Renown: Fame and its History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986. [↩]

- http://oddculture.com/2007/11/07/the-pekka-eric-auvinen-manifesto/ [↩]

- Gibbs, Nancy and Timothy Roche. “The Columbine Tapes.” Time 20 Dec. 1999 http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,992873,00.html [↩]

- Kellner, Douglas. Guys and Guns Amok: Domestic Terrorism and School Shootings from the Oklahoma City Bombing to the Virginia Tech Massacre. Boulder, CO: Paradigm, 2008. [↩]

- Serazio, Michael. “The Apolitical Irony of Generation Mash-Up: A Cultural Case Study in Popular Music.” Popular Music and Society 31.1 (2008): 79-94. [↩]

Really interesting piece. It reminds me of Bambi Haggins’s volume 7 discussion of Dexter (http://flowtv.org/?p=942) and the role of the sociopathic murderer in contemporary television. How does a fascination with Dexter or Tony Soprano compare to a fascination with Auvinen or Klebold and Harris? How are youth versus adult murders distinguished and represented in media? How does self-representation differ from fictionalized representation? What does each have to say about the other and the cultures from which they have emerged? About good, evil and moral gray areas? Can we ever see school shooters as morally ambiguous the way we see Dexter or Tony? Though obviously there are serious problems with comparing fictional television drama and user-generated digital media (not least of which is the issue of who are the media gatekeepers), both embody the “potential to narrate tragedy” (and potentially history) and to construct the meaning of tragedy in fascinating ways.

Pingback: Companies find value in the fame motivator « MediaBug

Pingback: » You say you don’t love youtube? Liar! Ideas for Discard