Monkey Magic

Karen Lury / University of Glasgow

This year the BBC hired the animator/illustrator Jamie Hewlett and the musician (ex-Blur front man) Damon Albarn to produce a 2 minute 10 second Olympics trailer that could be cut up into a variety of different stings. The result – the ‘Monkey’ Olympics trailer – has been the focus of extensive British press and web interest since the BBC’s coverage of the Olympics began. The 2-D animated film is in a sense a spin-off (a progeny?) of existing work by Albarn/Hewlett. Their collaboration began in 1998 with the emergence of the ‘virtual’ animated pop group Gorillaz and more recently with a fully fledged ‘Electro-Mandarin’ Opera – ‘Monkey: Journey to the West’ – which has played to rave reviews in Manchester, Charleston and most recently, the Royal Opera House in London.1 This week also sees the release of what one journalist called the ‘melancholy electro-ghost’ of the opera: the album ‘Journey to the West’ by the ‘band’ Monkey. Yet, all three monkeys are different, not just in terms of form but in tone, mood and appeal. As an Olympics ‘special’, I’m hoping to show readers something straightforwardly beautiful that you may not have seen, but I also want to suggest that the trailer might offer a particular and revelatory twist on those familiar concepts of hybridity, adaptation and convergence. In fact, I’ll stick my neck out over the finishing line to suggest that ‘Monkey’ offers a cross-platform, cross-culture concept that is satisfyingly dangerous, playful and open-ended.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yr5ZWYRaAyw[/youtube]

The narrative of the film follows very closely the opening title sequence of the Nippon (NTV) live action television series Monkey co-produced by the BBC and shown first in the UK in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The television series was itself a reflection of the folding hybridity of the ‘Monkey’ concept. Loosely based on an original seventh century Chinese novel Journey to the West (later attributed to Wu Cheng’en), the series was shot with Japanese actors in China and Mongolia. When it was transmitted on the BBC the actors’ voices were famously and – perhaps deliberately – very clumsily dubbed over with English dialogue using cod ‘Oriental’ accents. The four main characters are: Monkey, a brash, ‘punk’ immortal Monkey King who has been given a ‘wishing staff’ by a Dragon princess; Pigsy, a charming, but gluttonous pig monster banished, like Monkey, from heaven; Sandy, a cannibalistic water demon/monster; and Tripitaka, a gentle Buddhist priest who is a man but played by a woman (the characters themselves seem to recognise that he is both actually a man – since he is ‘their master’ – but also somehow and consistently actually that ‘she’ is also/and a woman).

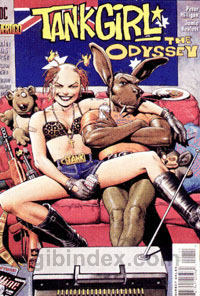

A playful, irreverent choice then: a trailer that reverses a mythic journey (from West to East) and which pays overt homage to a cult TV series that was never – in any coherent sense – an ‘authentic’ reflection or interpretation of Chinese culture or mythology. The music (which less enamoured critics have dubbed ‘Chin-easy listening muzak’) is a response from Albarn to his extensive immersion (three years worth) in Chinese music and culture but is clearly comprehensible to Western listeners who respond to it as both melodic and hip. The animation itself reproduces certain static poses and a colour scheme that may have been inspired by Chinese illustration and Japanese Manga; but for Hewlett fans, this is recognisably a Hewlett world – a world that is both menacing and cute (and where ‘cute’ is revealingly close to its roots in the freakish world of the side-show). It is funny and slightly unsettling as Pigsy smirks provocatively or when Monkey opens his mouth to reveal his dirty and surprisingly sharp teeth. Hewlett’s grotesque yet seductive style is reflected in his most famous creation before Monkey – the comic-strip post-punk heroine Tank Girl (whose boyfriend was a kangaroo). In interviews, Albarn and Hewlett are clear that they were happy to acquiesce to specific requests from the BBC.2 On the other hand, they are also clear that this is their ‘Monkey’ (however playfully this ownership is claimed.) For instance, they gleefully remind interviewers that they were both born in 1968 – the Chinese year of the Monkey. Not co-incidentally, this means that they are also the right age to have once been part of the original, obsessive and loyal audience for the TV series – made up mainly, but not solely, of prepubescent boys.

It is not cynical to point out that however distinctive it may be, the trailer is not just promoting the Olympics (and the BBC) but the Monkey ‘concept’ and therefore the Monkey ‘products’. However, it is mistaken, I think, to regard the concept and film as corrupt, inauthentic or ‘demeaning’ to the Olympic athletes and/or Chinese culture as some critics have suggested. Flow readers may have their own opinions but I want to comment on just two elements that seem to me central to its effect and potential: the representation of animals and the feeling of ‘lift’ generated by the music and style of animation.

Firstly, in its use of animals rather than people it may seem that the trailer is suggesting that the athletes are animals (Monkeys? Pigs?) Or perhaps it implies that the origins and manifestation of Chinese culture is bestial (or worse perhaps) ‘cute’?

Yes and no. Athletes are animals (they achieve at the limits of the human) and in their performance they transform from the functional inscrutability of an embodied non-human animal (all body) to the expressivity of the emotional human animal (using tears, voice and gesture) and all within a split second. Is this association degrading? Possibly. But in Hewlett’s world (as in Chinese mythology) there is a real ambiguity about how we interpret or use the ‘difference’ between humans and animals (remember; Tank Girl’s boyfriend was a kangaroo, he didn’t ‘look like’ a kangaroo he was a kangaroo.) The animals here are not anthropomorphised Disney-style, instead they balance precariously at the very boundary of animal/human (like Tripitaka they both are and are not, one thing or the other). This is what animation allows for and this represents a different world order in which ‘man’ (or the image of man) is not at the pinnacle of a ‘hierarchy of species’.

Secondly, in my experience it is relatively rare that television – particularly television fiction – produces moments of ‘lift’. By this, I don’t mean moments which ‘lift the spirit’ but that actual sense of a visceral tightening, a physical response in which your diaphragm is ‘lifted’, produced – possibly – by a gasp that lifts the chest up and which contracts the throat. A feeling of lift that is a mixture of excitement and anxiety, provoked most commonly by circus acts and in particular trapeze walkers. In fact and again not co-incidentally, it is the sort of exhilaration inspired by the wire work acrobatics in the film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. In the Olympics this sense of lift – the work of force made by the athletes which is often against gravity – is present in all sports. It is an element that links all the competitors since it refers not to the winning or losing of the game, not to the ‘fastest’ or ‘strongest’, instead it recalls the work needed and the joy inspired by self-propulsion. It is important that this force is related to actual effort: for in CGI (the form of animation used predominantly in other Olympics trailers) this propulsion is smooth, effortless; nothing is impossible and the work expressed reveals itself as the work of a machine. To make it believable an ‘organic skin’ is layered on (to flex, strain and perspire in fantastic detail) but all too often I think I can still see the machine in the monkey skin. In contrast, in 2-D animation the perceptible ‘in-betweens’, the space between frames, poses and drawings leaves room for me to gasp, to leap imaginatively. While in the trailer a variety of authentic and inauthentic cultural ghosts circulate and participate, at the same time, the touch of the animator (his work) is visible and tangible (and he in turn has responded to the weight, volume and texture of Albarn’s music). CGI, in contrast, would only present a sealed ‘perfectly imperfect’ environment for its athletes. While 2-D is entirely less realistic than CGI it is altogether more open and perhaps perversely more plausible. However smoothed by digital transference and filled in by CGI moves this particular film may be I don’t know, but in this apparently 2-D film I know I feel a lift as I glimpse the effort of the monkey in the machine.

Image Credits:

1. BBC’s Olympic Monkey

2. Albarn and Hewlett

3. Tank Girl and her boyfriend

4. Front Page Image

Please feel free to comment.

- Commissioned by the director of the Theatre du Chatelet in Paris the opera is directed by Chen Shi-Zheng and employs a cast of thirty Chinese acrobats. [↩]

- For example, in an interview with the BBC’s listing magazine the Radio Times, Hewlett comments: ‘The BBC wanted a minimum of five sports covered and we managed to get nine in, so they’re very happy. There’s hammer, hurdling, sprinting, javelin, gymnastics, swimming, diving, tae kwan do and pole vault.’ (‘Monkey Business’, Radio Times, 2-8 August 2008, p.20) [↩]

Pingback: Tama Leaver dot Net » Blog Archive » Links for August 22nd 2008

I appreciate the analysis of man/animal that is not demeaning, but even suggests that perhaps the animal is at the top of the hierarchy, and thus the comparison of “man” to “animal” is actually a reverse of power dynamics.

Chinese Performer (share the culture)

Chinese performer Kenny is grateful for the support of the share the culture

http://www.kennyren.co.uk

The Oct. issue of Runner’s World has a Pearl Izumi ad in it with the following copy:

“Running hurts. It always has. Woolly mammoths didn’t just roll over onto a plate and serve themselves up to prehistoric man with fries and a shake. They had to be caught – and running down woolly mammoths was a bitch. Guess what? Running is still a bitch. But one with a purpose. It teaches us that good things do not come easy. it teaches us that we are capable of more than we think. It teaches us that hard work will be rewarded and laziness will be punished. Don’t expect to learn those life lessons from running’s shiftless stepchild, jogging. Next time you suffer on the roads or trails, suffer proudly. It means you run like an animal.”

I just thought you might find the man as athlete/animal comparison interesting – they’ve launched an entire ad site, RunLikeAnAnimal.com

Pingback: The Tank Girl you (might) want « Feminist Music Geek