A Tale of Two Fan Girls

Bambi Haggins and Anna Jonsson / University of Michigan

On April 13, 2008, Bambi Haggins and Anna Jonsson, two self identified television scholars, continued a conversation about our evolving television viewing practices: in other words, we talked about being TV fan girls. If indeed the ways that we watch television reflect and refract evolving notions of both fan practices and communities, our attempt to mine our experiences may provide a basis for further rumination on fandom. Thus, this piece, an excerpt of a candid but cautious conversation, is casual discourse rooted in highly personal experiences—part lay theory, part critical/cultural theory. Our long-standing shared fan experiences allowed for a conversation interrogates our personal histories of fandom and its shifting definition, how the way we watch impacts what and how we watch and, in broader theoretical terms, whether or not different viewing practices make a different fan.

First of all, we need to explain what we mean by “fan girl.” We define this experience of fandom as involving the emotional, intellectual and social investment we’ve made in a handful of television series. We both intuitively think about being “fan girls” as participating in a community experience. However, interestingly enough, the actual earliest experiences of fandom did not fit the vision of friends gathered around the television. Haggins’ childhood love of M*A*S*H caused weekly arguments with her younger sisters (The Wonderful World of Disney fans): “Half the time, I would lose but, if I got Pop to watch with me before the whining about Disney started, I’d win.”

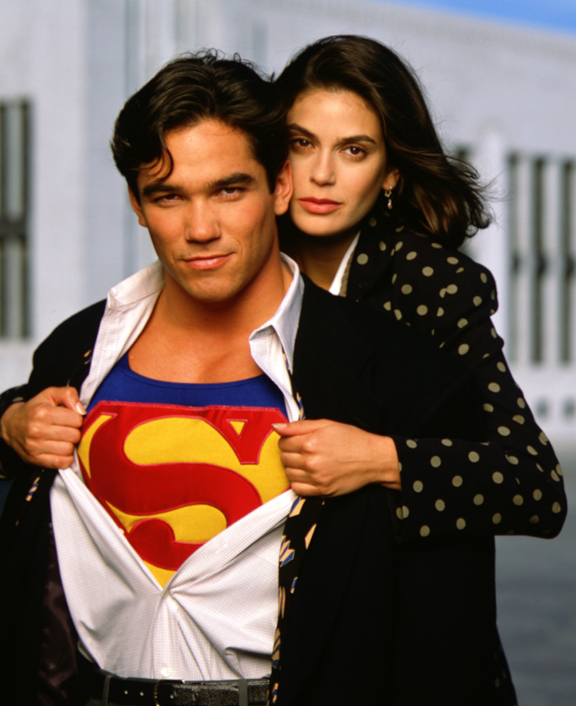

Although one of us (Haggins) asserted that fandom was a communal endeavor, her first example of fandom was an assertion of taste that was not shared by all. On the other hand, as aptly noted by Jonsson, the other’s first example of fandom exhibited “little taste at all” but provided a template for future fannish practices. Her show was Lois and Clark: the New Adventures of Superman (Sundays, ABC). As a “really big science geek,” the fannish practices of her Trekkie science teacher (although not the fandom) had an impact: “A group of geek girls and our teacher always started the week by swapping opinions on the last night’s show.”

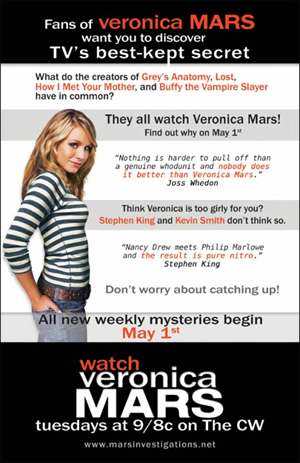

There was a time when a fan would have to be home on Sunday night for M*A*S*H, Lois and Clark or The X-Files. During the VCR era, taping was not preferable to watching the series in real time, because “appointment viewing” helped to establish a viewing community. Back in the day, meeting up with a group of like-minded folks and watching the series (on the day it was first aired) acted as personalized event programming: a mini-con of friends indulging in their fandom with others. This kind of viewing, designed for old school network/ netlet broadcast platforms, has waned. By Veronica Mars, alternately loved and hated by many fans (both of us included), it was harder to maintain the weekly get together and easier to watch on the UPN/CW website, iTunes or stored at home with TiVo. While varying formats for viewing may alter the circumstances of a shared spectatorial moment, being able to archive episodes on DVR or to expect the quick turnaround onto DVD has made the marathon viewing experience a commonplace way to watch television programming. Although one may miss whatever your particular salad days of televisual fannish practice might have been, one fact remains constant: fan girls are made and not born.

Undoubtedly, our fan moments were highly influential in terms of our personal notions of distinction, identification, pleasure and quality: our fandom provided methods of carving out social space. However, the evolution of our specific taste cultures—whether designed to assimilate or to differentiate ourselves from the dreaded “mainstream”—remains an integral part of our fan girl identities. Throughout our coming-of-ages as fan girls, separated by two decades, we continued to re-position ourselves among shows that articulated a discourse about taste that wasn’t available outside of television. The interplay between “hipster” and “geek” was a common theme in our choices and in the style of these particular narratives: The X-Files and Buffy the Vampire Slayer are built on elaborate mythologies constructed with deadly seriousness as well as self-reflexive humor. Our investment increased as series’ taste positions were revealed, allowing us to enter and engage with the shows’ fan communities.

According to Haggins, the fan girl experience is associated with the passion for a series “and the need to make others understand it in the same nuanced terms that I do. It also has to be a show that not everybody will immediately appreciate.” While love for quickly lauded series (i.e. The Wire) does not require a fannish offensive to convince others of its quality, the fact that series like Buffy seem to need fans inspires our defensive loyalty. Furthermore, the imagined and real interaction between creative forces and those who, through repeated viewings, blogging and fan discourse, have gained series’ expertise feeds the desire to build community and to bring more people into the fold—whether on old school fan sites like David Duchovny Estrogen Brigade and The Bronze, or the fan boy/girl Mecca, Television without Pity. Haggins adds, “the conversion process and the joy of the viewing parties are huge parts of my fan girl ethos. …more with Buffy than X-Files. Heck, I developed a class to convert the masses. ‘Give me 5 episodes, I’ll make you a fan.’ Most the time I succeeded.”

“Making fans” became a pleasurable challenge and required a nuanced perspective on taste, cutting across “high” and “low” culture alike. Yet “making fans” also describes a process of self-education that we both identified as being critical to our experiences. The Internet was a frequent tool for gathering and collecting pieces of information, news, and gossip. In short, these were collected pieces of social capital to be exchanged and compared as part of the fan community. Jonsson describes what first made her feel like a fan girl: “Downloading sound files of BtVS quotables. I had all these sound files on the family computer, but I didn’t know what to do with them.”

While we both understand and exercise fan-making behaviors, Jonsson, who grew up an online forager is comfortable with the notion that you can seek a community online that you can’t find at home. Haggins, a lurker, is not. Jonsson says, “I watch TV online on my own time (though I made a point of going downstairs to the big TV during the writers’ strike). I’m a fan of the podcast The Planet (for The L Word fans). I’m really more dedicated to the podcast than the show itself.” The podcast often positions itself in conflict with the series and provides a participatory collection of show knowledge and listener input, without which, it could not thrive. Jonsson cites having “limited expectations given the fact that the hosts have real lives and they’re doing this in their free time.” This does not negate the fact that fan investment—the effort, energy and time dedicated to develop a fluency regarding the narrative, production history and fan culture of a given show—also breeds high expectations.

The annals of our girl experiences end in the same vision of watching Veronica Mars—although Haggins saw it as a transition point in terms of a loss in the shared group experience of watching shows at the time they aired. We may no longer privilege the friends gathered around TV image but we still crave the fan exchange of ideas and expertise. Undoubtedly due, in part, to a global audience that will not be constrained by the inconvenience of regional broadcasting, something is happening to “liveness” that alters the way both of us assert ourselves as fans.

Fan girls know that—whether podcaster, lurker or scavenger—the more closely you monitor, the more you are rewarded as a fan. If constant practices of monitoring and marathon viewing overtake the “live moment” of a show’s original broadcast, do the social and community aspects of fandom change? Or is it possible that we might just become better fan girls?

Image Credits:

1. Lois and Clark was a first foray into fandom.

2. I still want to believe in Mulder and Scully.

3. Inspiring Whedonists Everywhere: Joss Whedon and the cast of Buffy the Vampire Slayer (Season 5).

4. The L Word fandom via podcasts from The Planet.

5. Fans—some with industrial cred—showed love and saved Veronica Mars (at least one time).

Please feel free to comment.

Pingback: A Tale of Two Fan Girls « Serial Anna

I have been wondering this same thing for the last several years, whether the shift towards “on demand” viewing and the marathoning of shows (which I do myself with “Bones” right now) might impact fannish responses. Given how my friends tend to freak out after new episodes of their favorite shows – the “Torchwood” finale was quite the humdinger apparently – I don’t think that sense of simultaneous engagement and shared experience is going away entirely any time soon.

But I could see a split developing between people who watch a show live and then get together and talk about it versus people who watch in clumps or later on. It could be as innocuous as a fan feeling slightly late to the party, or it could reduce the number of people taking part in fandom depending on how much time passes from the airing of an episode (people who come to shows late, especially if the show goes off the air, may miss the active phase of a fandom entirely).

Stephanie, you raise a great point about the split(s)in fan viewing practices. It’s funny when Anna and I started working on this piece; it was all about the viewing party for me–a dip into nostalgia about my early days of fandom as group work. Given the ridiculous number of X-Files VHS tapes that I have hauled all over the country with me, it seems that TiVo, On Demand or DVD releases were not requirements for staging fan making marathons back in the day. However, having come late to the BSG game and having viewed Seasons 1-3 on DVD or online, my viewing practices are markedly different: I have actually stockpiled 3 episodes of BSG because watching just one (the season premiere) made me crazy. If the split between “view it now” and “view a lot of it later” folks is about more than just comfort (with platforms) and convenience (on demand viewing), how and why do our fan practice often vary and which practice makes us “feel” like better fans?

well, not everyone has access to emerging tv technologies like TiVO, so some of us still watch TV “the old-fashioned way”. plus, I just can’t get used to watching TV on my computer. it’s so uncomfortable! computers discourage communal viewing and encourage solitary viewing, something I don’t necessarily enjoy. my computer is for post-show follow-up – reading reviews and posting comments about ‘last night’s episode.’ I do know people who like to ‘binge view’ – they’ll watch a season’s worth of a show in a day or something. that also assumes you have the leisure time necessary to devote to such viewing practices. I find all of this fascinating, especially as someone who is working on the fan practices of female RTV viewers, but there’s a lot that still needs unpacking. We take a lot of ideas and practices around TV viewing for granted.

in some ways, I think binge viewing takes away from fannish responses – it makes TV more disposable than it already is. I tend to forget about a show a lot quicker when I watch it over a short period of time, as opposed to slowing building a relationship with it (i.e., characters, plot lines) over a longer period of time. no doubt, all of these technological changes have altered fan practices, in many ways making them very disperse and fragmented. definitions of fandom are changing altogether. It would be interesting to think about ‘resistant’ fan practices as well and how some people have been slow to accept or adopt new technologies, preferring pre-technology practices instead.

I feel like the way a show is viewed has nothing to do with fan practices at all anymore. Since the dawn of the Internet, fandom communities have been, for the most part, online. I think that the community viewing that was mentioned in this article was just a precursor for the online community, which is now global. Fan practices now boil down to what you contribute to the community, not when you view the show. Henry Jenkins III mentions in his article, “Star Trek Rurun, Reread, Rewritten: Fan Writing as Textual Poaching”, that the fans become an active participant in the show. From personal experience, writing, drawing and discussion are what now separate the fans from regular viewers. And for this, viewing times does not seem to make a difference so long as one makes insightful comments for the community. It is the ability to watch certain scenes of a show again in order to notice something new and make interesting observations that currently. So yes, I suppose I would have to say that the community aspect of fandom has changed. It has gotten to a point where fans themselves are judged on their ability to write, etc. and the show is just the backdrop for this to take place. Unlike Jenkins’ article suggests, in order to express yourself within the fandom, you must play by the rules since the communities, as a whole, have become stricter with what is “acceptable” thanks to the technology that allows people to monitor shows.