Notes on Children Unlike Others

by: Olivier Tchouaffe / FLOW Staff

This article’s modest aim is to analyze the evolution of two child soldiers–Ishmael Beah and Ocia Jacobs–from mercenaries to international peace activists, as a pretext for discussing the importance of global media’s intervention in the moral and ethical debate on pacifist policies against the travesties of biopolitical machines and regimes of exception. My aim is to highlight how these child soldiers have achieved authentic status as international standard-bearers of pacifist politics. Their public personae engage with Foucault’s warning in Discipline and Punish (1991) about the paradox of authoritarian regimes which constantly require their citizens to give up more rights in exchange for security, while hardly bringing peace. These former child soldiers signal that such regimes continually press their totalitarian thumbs on the population in order to industrially produce an incessant contingent of docile bodies in order to fight wars without end. In practice, Beah and Ocia’s argument suggests that long-lasting peaceful settlements are condition sine qua non for real security, rather than war without end.[i] This argument means rethinking notions of sovereignty in terms of social partnership driven by egalitarian relationships, rather than strictly racial, ethnic, or national boundaries.

The sight of an Ishmael Beah on American TV, exuding a credible boy-next-door charisma for a former child soldier, represents a unique opportunity to witness a fascinating act of career reinvention while simultaneously measuring the tenacity of one young man’s soul, revealing in the process the strong nature of a child’s resiliency[ii]. His image challenges the viewer not to look at the child soldier’s phenomenon in the exclusive term of victimization. Beah’s campaign clearly aims at resisting the media storm created around the image of the child-soldier, which seeks to immortalize these individuals in our global popular culture as an emblem, a strange, weird, soulless and cold-blooded creature [iii].Beah’s international media campaign, first and foremost, puts a face to these images and relies on his specific experiences as a former child soldier in order to redress the unbalanced reporting regarding African wars by “parachute journalists” or “Drive-By-Media practitioners.” Such media professionals seem charged by sensationalistic spectacles of limb amputations and horrendous atrocities, each described while floating over the crucial question of why idyllic, loving communities based on a strong millennial humanist traditions and respect for the elders can collapse in such sad, tragic and violent ways into a society of death. Consequently, this kind of journalism is nothing but a tissue of prejudiced anecdotes with no subtext beyond voyeurism.

Beah argues that it is important to understand that the child-soldier experiment is primarily an immoral and failed experiment that can happen anywhere in the world, not only in Africa. The child soldier phenomenon is above all the product of failed states, in which the postcolonial state government’s loss of control over populations and resources opens a way for the rise of what Achille Mbembe calls “private interest governments.” These governments constitute themselves as “war machines,” often redefining sovereignty largely through the capacity to dictate who must live and who must die. Political compliancy, within this context, is achieved through violence enshrined as the sole policy of management of resources and populations.

In practice, the role of these war machines is to wage war against “enemies of the state” which are peoples, actively or passively, resisting their dictatorships[iv]. These negative modes of power and thanatography can happen anywhere, as the child soldier is the product of the proliferations of these “war machines” globally. Consequently, there are 300,000 child soldiers active in close to 75% of ongoing conflicts across the globe in places such as Burma, Sri-Lanka, Colombia, Democratic Republic of Congo and Afghanistan. It is important to note that the first American casualty of the Afghan War occurred at the hand of a Taliban child-soldier[v]. Within this context, Beah’s experiences as a child soldier and his public message urge us to understand “war machines” as a way to make sense of the processes of the devaluation of human lives. His media appearances evoke the animalistic desperation emanating from lives reduced to bare-bones survival needs such as shelter, food and sex, the madness of indiscriminate mass-murders, the catch-22 of killing or being killed, the vicious cycle of revenge-killings embedded in the cocktail of ethnic, religious propaganda and hatred mixed up with drugs and alcohol on impressive minds. It is a vicious system where at the end it is difficult to tell the victims from the perpetrators because all the participants end up losing their souls[vi].

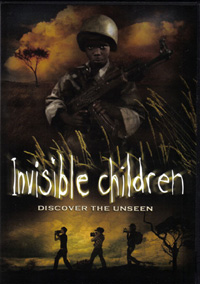

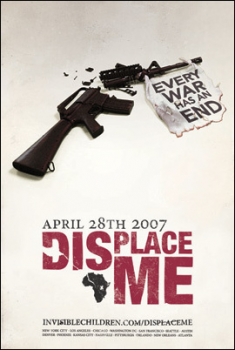

Through a different amalgamation of media, Ocia Jacobs and Invisible Children (2005) are putting many individual faces on the totem of the child-soldier and internationalizing its repertoire with “Displace Me” events. The movement stems from a documentary featuring three film students, Jason Russell, Bobby Bailey, and Lauren Poole, and their work in Northern Uganda with child soldiers being abducted into the insurgency of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA). The LRA was formed in the 1980s when citizen Alice Lakwena claimed to have received a command from the “holy spirit” to overthrow the Ugandan Government. As the result, this 20-years-old conflict between the LRA and the Ugandan government has displaced more than 1.4 millions people from their homes. More than 30,000 children have been abducted into the LRA to serve as soldiers, and in the case of young girls, as sexual slaves. The documentary makes the claim that these children constitute the bulk of the LRA forces. One of the main characters of Invisible Children (2006) is Ocia Jacobs, who was abducted into the LRA as a child, but managed to escape and hide in the bush for many months in fear of being recaptured. Ocia Jacobs is now one of the famous faces of the recovered child soldiers and a spokesperson for “Displace Me.”

“Displace Me” events, organized by Invisible Children Inc., are designed to simulate the lives of child soldiers, in which young people build cardboard huts and share small rations of crackers and water, with no bathrooms or showers, are organized to simulate the lives of child soldiers. The events make the resounding statement that children are all the same regardless of as national identity, race, class, education or gender, which in this case, are no longer considered sources of divisions but limitless potentialities for community. The organizers also ask participants to write letters to lawmakers requesting help for the child soldiers. Here in Austin, this event took place at the Travis County Exposition Center on Saturday, April 28, 2007. Furthermore, this year, Invisible Children Inc. organized thirteen teams to present their documentary in churches and schools across America.

Beah and Ocia’s media campaign are examples of the practice of pacifist politics that embrace a basic universal condition of loyalty to all humanity, reminding viewers that this loyalty has an instinctive, personal statement. Moreover, the pacifist movement frames itself as part of a larger culture which has demonstrated results throughout history with moments such as the abolition of slavery, the independence of India, the Civil Rights Movement in the United States, the campaigns to end the war in Vietnam, and the work of contemporary international tribunals putting war criminals such as Charles Taylor on trial[vii]. Consequently, pacifist politics presents itself as a serious commitment to humanity, an urgent political discourse of hope, an incessant contribution to peace against the absolute totalitarianism of biopolitical machinery. Absolute totalitarianism, represented by warlords such as Charles Taylor, is directly opposed by the political statement that their kind of mass-murderer will never be strong enough to escape the international criminal justice system. The institutions of such international justice, such as The Hague International Tribunal where Charles Taylor will soon be put on trial, have the international legitimacy and legal instruments necessary to hold war criminals personally responsible for the mayhem they have brought to their countries. Within this context it is not warlords or powerful politicians leading the way, but ordinary people–such as Beah and Ocia–following their own ethical and moral conscience. Pacifist politics, therefore, begin with recognizing that peace, not war, best serves the interests of security. Within this context, even warlords are not above the law.

Pacifist politics, consequently, is the recognition that the other is the beginning of morality and that by treating him well, we are signaling how we ourselves want to be treated as well. Therefore, the powerful lessons that Beah and Ocia are bringing forth into our contemporary media discourse suggest that every generation must define itself, even if this requires breaking away from families and the parts of the past that caused the community to descend into savagery in the first place, namely clanism, tribalism, ethnocentrism, racism and other prejudices. Within this context, the rule of law is entrenched as more powerful than the pre-democratic and anarchic violence of tribal linkages and loyalties which must, therefore, remained confined to the state of nature, not the state of civilization. Within this context, pacifist politics become a form of ethical exigency in order to enforce and practice a language of democracy against a language of oppression even coming from the intimacy of the family or the community.

I welcome comments on this piece.

Sources

[i] I take the opportunity to recognize that this piece is exclusively from a male perspective. Girl soldiers do also exist. They will be the subject of a subsequent article.

[ii] Beah made appearances on the Jon Stewart’s “The Daily Show” on February 14, 2007 on Comedy Central and on C-Span Book-TV on 5/9/2007.

[iii] See also films such as Lord of War (2005) and Blood Diamond (2006).

[iv] See Achille Mbembe, “Necropolitics.” Public Culture 15, 1 pp. 25-40 (2003).

[v] Jimmie Briggs lecture: Wednesday, Nov. 15. 2006, University of Texas at Austin; also, Innocents Lost. Basic Books, New York, NY, 2005.

[vi] This has roots in the work of social psychologists such as Philip Zimbardo, who began his research with the famous Milgram Experiment in the Stanford Prison Experiment in 1971 in order to demonstrate that pressure to conform can lead stable people to practice antisocial, sadistic behaviors. In The Lucifer’s Effect (2007), he tackles the breakdown of the chain of command in the Iraqi prison of Abu-Ghraib and the sadistic orgy of sex and violence that ensued.

[vii] On Tuesday June 20th, 2007, Charles Taylor, former president of Liberia and one of Africa’s most brutal warlords, was secretly flown under heavy security from Sierra Leone’s Special Court to The Hague, where he is due to stand trial for his part in the atrocities—including the conscription of child soldiers, sexual slavery and mutilation—carried out by rebel militias he backed during Sierra Leone’s savage 11-year civil war. The surprise move came just four days after the United Nations Security Council had voted unanimously to authorize his transfer.

InvisibleChildren.com

The New York Times

Image Credits

Olivier,

Thanks for an engaging and enlightening article! Like Hector’s article about the children in Hutto’s Detention Center, this article speaks, at least to me, of the ways that children are continuously evoked to raise awareness of issues–presumably because the general public will express more indignation and perhaps act if we say, “look at how children are being used/abused/etc.” Additionally, by providing insight into what children (or adults who speak of their childhoods) have to say when they speak, these articles also implicitly raise the issue of how children are, within adult ideologies of war and immigration, particularly silenced by those adults who, for the sake of agendas, actively choose not to see children as human beings but rather weapons in those wars.

As you argue, not just for children, but for the sake of global humanity, we must each evaluate what we can do, and what we can incite our governments to do, to stop machineries of domination that daily divide us and in the process destroy the very fabric of our future.

I want to thank Olivier for raising such important issue as children soldiers. It is a huge human rights problem and a philosophical one that reminds us of the ways in which ideas of citizenship construct puzzling social practices. Most of the cases that Olivier mentions (e.g., Colombia, Congo, Burma) are cases where the children become soldiers not under the official tutelage of a nation. Most of these children soldiers are recruited to fight against nation-states, as these are represented by military forces with the power to draft from civilian populations. Anti-government forces, often without resource to traditional politics or legal drafting powers, must engage in long conflicts against the state and eventually may need to abduct children in order to “man” their armies, and they do. I am not clear about how to think about citizenship in these cases, since most of the discourse used trying to protect the children soldiers, as Olivier correctly points out, borrows from human rights discourse. Is this because national discourses of national rights are insufficient? Consider this. In the US, our armies do not officially have the power to draft or abduct; yet, children soldiers are also present in our armies. Since the invasion of Afghanistan, the American armies have been aggressively recruiting high-school students, who often enroll and go to training while in school, and while they are officially children, without the right to vote, drink, or the legal power to enter into contracts. The Supreme Court has decided that this practice is ok thus forcing us to question fundamental definitions of citizenship. If children are otherwise legally defined as always in need of protection by the state, why is this practice legal? I have a cynic’s answer to this one. In the US, like in Congo or Colombia, children are assets that can and will be used by “citizens” to further their political goals. Children are property. Furthermore, our ideas about citizenship and rights are based on naive understandings of the state as a benevolent organization, in spite of the fact that history shows the opposite. States, and the discourses of rights and citizenship, are borne out of violence and violence has remained at the center of the discourse of citizenship.