Everybody Hates Chris and the (Overdue) Return of the Working-Class Sitcom

by: Tim Gibson / George Mason University

Everybody Hates Chris

One of the best things I’ve seen on television recently was shot from the perspective of a garbage can. This particular shot comes in the middle of the pilot episode of Everybody Hates Chris, a semi-autobiographical sitcom that chronicles the middle-school experiences of comedian Chris Rock in early 1980s Brooklyn.

In the pilot, we learn the basic premises of EHC. It is 1982. The Rock family has just moved out of the projects and into their new home—a two-level apartment in Bedford-Stuyvesant. Young Chris is excited about the move and the adolescent adventures that await him now that he’s turned thirteen. His excitement vanishes, however, when his mother informs him that he’ll be taking two buses everyday to become the only black student at Corleone Middle School—all the way out in white working-class Brooklyn Beach.

In this way, two social spaces generate most of the show’s comic energy. Class issues are largely explored in Chris’s home life, while the show’s writers use Chris’s travails at Corleone to foreground questions of race.

This brings us to the garbage can. Early in the show, we learn that Julius Rock, Chris’s father, works two jobs and counts every penny. Julius, it turns out, has a particular talent for knowing the cost of everything. When Chris goes to sleep, Julius tells him, “unplug that clock, boy. You can’t tell time while you sleep. That’s two cents an hour.” When the kids knock over a glass at breakfast, Julius says, “that’s 49 cent of spilled milk dripping all over my table. Somebody better drink that!” And when someone tosses a chicken leg into the garbage, we see Julius peer over the rim, grab it, and exclaim, with a pained look on his face, “that’s a dollar nine cent in the trash!”

To be sure, as a former early 1980s middle-schooler myself, I enjoy the retro references to Atari, velour shirts, and Prince’s Purple Rain. But what I like most about EHC is how it foregrounds the experience of class inequality. Unlike other blue-collar comedies (e.g., According to Jim, Still Standing and King of Queens) which signify their characters’ working-class status via lifestyle choices (i.e., wearing Harley shirts, drinking beer, listening to Aerosmith, etc.), EHC generates much of its comedy directly from the class-based experience of struggling paycheck to paycheck and never having enough to pay the bills.

And so, in one episode, we see Julius buying the family’s appliances from Risky, the neighborhood fence, because the department store is simply out of reach. In another, Julius and Rochelle (Chris’s mother) agree to give up their luxuries (his lottery tickets and her chocolate turtles) in order to pay the gas bill. Things go haywire, however, when Rochelle (now reduced to getting her sugar fix from pancake syrup) catches Julius sneaking out to play the Pick 5.

And during one dinner, when Chris finally gets up the courage to ask for an allowance, Julius delivers a lecture familiar to every working-class kid. “Allowance? I allow you to sleep at night. I allow you to eat them potatoes. I allow you to use my lights…Why should I give you an allowance, when I already pay for everything you do?!”

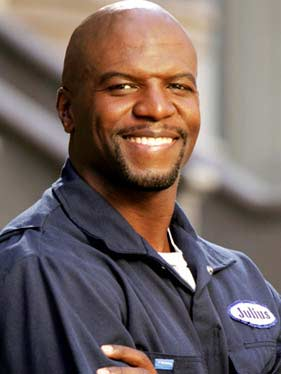

Terry Crews as Julius Rock

What makes this focus on class all the more remarkable is that it comes to us in the form of a so-called “black sitcom.” As Timothy Havens notes in his study of the global television trade, international buyers looking to pick up American sitcoms strongly prefer “universal” to “ethnic” comedies (their words, not Havens’). As Havens quickly makes clear, however, the term “universal” is essentially code for white, middle-class, family-focused shows of the Home Improvement variety.

Thus, in the international TV marketplace, a white, middle-class experience becomes universalized as something that will appeal to “everyone.” Steeped in this discourse of whiteness, distributors reflexively brand as “too ethnic” any shows that deviate from this norm, including especially sitcoms that, as Havens writes, “incorporate such features as African American dialect, hip-hop culture…racial politics, and working-class…settings.”

Given the important role played by international sales in the profitability of American television programs, this hostile distribution environment makes it less likely that shows with African-American casts will be produced in the first place.

The breakthrough success of The Cosby Show in the 1980s, of course, pointed a way out of this particular cultural and commercial box.

As Sut Jhally and Justin Lewis note, Cosby struck an implicit bargain with white audiences in the Reagan era. In exchange for white viewers inviting the Huxtables into their homes, the show’s producers would banish explicit references to the politics of race and keep the narratives focused on “universal” family themes. You’ve seen the show. Theo gets a “D” in math and receives a stern lecture from Cliff. Cliff’s attempt to cook dinner for the family ends in disaster. A slumber party for Rudy gets hilariously out of hand.

But, equally importantly, because white audiences have historically associated poverty with “blackness” and coded middle-class status as “white,” The Cosby Show placed these family-friendly stories in a context dripping with wealth and class privilege. In the end, this complex interpenetration of class and race in the dominant cultural imaginary allowed many white viewers (who might otherwise have been reluctant to watch a “black sitcom”) to read the Huxtables—an upscale African-American family focused on the peccadilloes of everyday life—as “white” and therefore “just like us.”

The commercial fortunes of The Cosby Show have thus left an ambiguous legacy. Its path-breaking success has undoubtedly provided subsequent producers of African-American sitcoms with rhetorical ammunition to take into the pitch room (“Cosby made $600 million in its first year of syndication!”). In an industry built on the endless repetition of past success, this is no small contribution.

Yet the middle-class, family-focused formula for African-American sitcoms—the model that signifies “universality” to international distributors and buyers—has also proven to be an ideological straight-jacket. To get on the air, in short, class must be dismissed. Thus, shows like The Fresh Prince of Bel Air, The Bernie Mac Show, and My Wife and Kids reproduce the upscale Cosby formula in exacting detail. Even programs like Girlfriends—shows that jettison family-focused themes for a more hip and youthful sensibility—nonetheless take great pains to place characters into high-end, even lavish, settings.

This raises the question of how EHC got on the air in the first place. Undoubtedly, the star power of Chris Rock, the show’s co-creator and narrator, played a central role. This said, I would love to know more about exactly how artists like Chris Rock draw upon their accumulation of symbolic capital—including their professional prestige, their network of connections, and their track record of commercial success—in order to overcome the ideological limitations of the industry’s commercial “common sense”

Indeed, perhaps this is a question that future political-economic work in television studies could productively explore. If we knew more about the conditions in which such accumulations of symbolic and social capital can be strategically applied to open new ideological spaces in the industry, we could create cultural policies that encourage this process.

In the meantime, I’m rooting for the future success of EHC. Admittedly, I’ve only seen the first season DVDs, so disappointments may be waiting. Still, for placing the struggles of working families at the center of its narratives, and for presenting the working-class experience as more than a matter of consumer choices, EHC has earned a valued place in my Netflix queue.

Chris Rock and Tyler James Williams

Notes:

Timothy Havens, “‘It’s Still a White World Out There’: The Interplay of Culture and Economics in International Television Trade,” Critical Studies in Media Communication, vol. 19, no. 4 (December 2002): 387.

Sut Jhally and Justin Lewis, Enlightened Racism: The Cosby Show, Audiences, and the Myth of the American Dream (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1992).

The $600 million revenue figure came from Yahoo.

Image Credits:

1. Everybody Hates Chris

2. Terry Crews as Julius Rock

3. Chris Rock and Tyler James Williams

Please feel free to comment.

Another show which places the working class family at the center (or one of the centers) of the narrative is Ugly Betty. Like EHC, Salma Hayek is the star executive producer. While this is more a question than a comment, I wonder how representations of Latino-ness and the working class experience compare with EHC? How is the African-American community responding to this show? Is this a new trend in the network family sitcom? Or as Gibson questions, does star power perhaps trump everything?

Adoro esse seriado…….

Beijos…..

Aqui no Brasil TODO MUNDO ODEIA O CHRIS é sucesso!!!!

One of the really great things about Everybody Hates Chris is that it works as a “universal” family sitcom while at the same time addressing the issues of race and class. So many other shows only do one or the other. The Cosby Show focused only on the family and issues that would apply to any affluent and functional family of the time. On the other hand, other sitcoms featuring African American families, such as Good Times, mostly focused on race and class, thus alienating many white and middle class viewers. The Rock family is portrayed as a family that everyone can relate to regardless of the viewer’s background. The Rocks face the same issues as most other families, such as petty arguments and unruly children, while at the same time never forgetting who they are and where they come from. Their race does not disappear as it did with the Cosby family, but at the same time, it is not the main focus of the program. The Rock family maintains a delicate balance between racial identity and personal identity.

These days it is slightly unusual to see a working-class sitcom that focuses on an African American family. So often when a show’s central family is black, they are also wealthy, or at the very least earning a comfortable living, such as on The Hughleys and My Wife and Kids. This is perhaps because the connection of race with class is a very sensitive subject which is not easily tackled within the limits of a family sitcom. As mentioned in this article, Everybody Hates Chris is different from other shows from its genre because “unlike other blue-collar comedies…which signify their characters’ working-class status via lifestyle choices…, EHC generates much of its comedy directly from the class-based experience of struggling paycheck to paycheck and never having enough to pay the bills.” It is not an easy thing to do to put an African American family on television and have them struggle to make ends meet, while at the same time making it clear that it is their situation, not their race, which is the cause for this struggle. With today’s murky ideals of race and class and presumed racial equalities, many viewers have a tendency, as explained by Darnell M. Hunt in his essay Making Sense of Blackness on Television, to believe that “black Americans who had not achieved the American Dream had only themselves to blame.” Everybody Hates Chris portrays a different side to this way of thinking, showing that a family can work hard and save money the best they can, but still struggle. First and foremost, however, this is a family sitcom, and the show never looses sight of how despite all of the obstacles the Rock family faces, the most important thing is that they have each other. This is a message that all families can embrace, regardless of race or class.

According to the terminology used in Gibson’s article, Hannah Montana would fall under the deceitfully-termed category of “universal” comedy, as it is considered white, middle-class and family-focused. In order to maintain its “universality” it pretty much avoids serious racial or class issues. In fact, since it’s a comedy the writers and producers seem to think it’s harmless to perpetuate disturbing stereotypes. How could it be dangerous to subconsciously impart these stereotypes on future generations at such a young age? Apparently Disney doesn’t have an inkling of a clue.

One of the best examples of the stereotyping and caricaturizing of a non-white character is with the character Roxy. Roxy is Hannah’s tough, overprotective bodyguard who used to be a U.S. Marine and fits perfectly the stereotype of black women having attitude. She’s also sort of dehumanized as she compares herself to an animal with one of her catchphrases, “Roxy like a puma!” In one episode, she concocts some sort of voodoo-type potion for her employer. I couldn’t help but be reminded of a similar stereotypical persona of the housekeeper and attendant –Dorita- from the Chevy Chase movie, Modern Problems, whose use of witchcraft and voodoo serves as a sort of caricaturized cultural distinction that is supposed to be humorous.

There is a specific episode, “School Bully,” from season 1, in which Roxy has a relatively prominent role. Hannah is being picked on by a bully, a white girl who seems, by her appearance, to be lower-class and who happens to be nicknamed “Cracker,” as she cracks her knuckles a lot. The double meaning, which I guess was lost on Disney (yeah right), becomes apparent when Roxy chases the bully in Hannah’s defense saying, “Come on, this puma’s hungry for some cracker.” See for yourself at the link below at around 3mins 50 seconds:

http://www.youtube.com/watchv=.....re=related

In addition, Hannah’s two biggest nemeses are Ashley who is African-American and Amber who is Asian-American. Both are the popular girls who are portrayed as superficial, mindless and mean to Hannah. It’s odd that they are often the only non-white characters in the show, and their sole purpose is to serve as Hannah’s air-headed, depthless rivals.

As far as how class is represented, Hannah’s family seems to have been a middle-class family who suddenly got rich through her musical career. There are a number of references that seem to support their portrayal as sort of under educated, country bumpkins who have suddenly come into money. Hannah’s dad usually drops all of his gs and says things that poke fun at southern euphemisms. For example, he says, “You know what they say, every now and then even a blind pig snorts up a truffle.”

This southern bumpkin image is magnified when uncle Earl comes to visit. He storms in with a potbelly, suspenders over his flannel shirt and a potato sack carrying roadkill that he “ran over in Texas” and wants to grill up. The show survives on unabashedly perpetuating stereotypes.

“Everybody Hates Chris” reminds me of the dark sitcom being represented in “It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia” The series allows for a lot of delicate social commentary to be explored. Take for example the episode entitled “The Gang Goes Jihad” where we follow the gang as they try to save their bar from being destroyed by the property’s new owner, who happens to be Israeli. Another storyline in the same episode provides a look into rich versus poor as we watch Frank and his estranged wife argue over money.

Before getting into that, let’s backtrack to the main characters. Mac, Charlie, Dennis, Dee, and Frank are owners of the failing Paddy’s bar on the wrong side of Philadelphia. All of these characters aren’t what you would call highly educated or financially well off, almost making their excessive behaviors excusable. These ingredients provide the groundwork for a very different look at race and class, much like “Everybody Hates Chris” does (though not nearly as extreme).

That brings us to the aforementioned episode, where the gang (Charlie, Dennis, and Mac specifically) does a series of childish stunts like toilet papering the property and lighting a bag of feces that inadvertently causes a building to explode. This is further complicated when they look like the perpetrators of a hate crime after the “Jihad Tape” they made (but weren’t going to show publicly) is accidentally left at the scene.

The most interesting aspect of this particular plot is the continuing argument about how to refer to the new property owner: Jew or Jewish? Specifically “what is the right context?” There is a continuing dilemma over what constitutes as a racial slur. However, none of them are the right people to ask as Dennis and Mac explain to Charlie that what is going on in Israel is a “War on Terror” against the country’s leader Saddam Hussein over the massive amounts of oil Israel has. Yes, ladies and gentlemen, they’ve confused Israel with Iraq, a mistake that is wrought with implications that will have to be explored another time. In the meantime, I believe it’s safe to say that what this episode has said about the topic of race is that some people don’t seem to understand it and come off as fools or racists in extreme cases.

Another storyline follows the relationship between Frank, his estranged money-hungry wife and their strapped-for-cash daughter Dee. We explore how the opposite ends of the economic spectrum collide through Frank’s insistence on getting back at his wife by stealing her beloved dog and the fight Dee and her mother have over a pair of earrings, the later completely ignoring Dee’s neck brace. This particular story is best summed up with one of the episodes last lines: “Why can’t you just die and leave your money to your kids like normal parents of America?” Proving that no matter what class is represented, the all mighty buck is very important to the family dynamic.

“The way It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia” approaches such topics reminds me of “The Simpsons” and “South Park”, two other shows that constantly blur the line of appropriateness for the sake of comedy and commentary.

i watch that show and i crack up so badly Chris your funny

Love the show! i even review it in my blog! :P

I love this show because it is something my whole family enjoys and I won’t have to worry about dirty jokes for my kids. Just the way he relates his life to something anyone can relate to is amazing. Thanks so much for making the show. It is my favorite comedy of all time.

i love tyler james williams cat

Sinceramente essa série é simplesmente incrível, pois Todo Mundo Odeia O Chris. Aliás o Brasil Odeia O Chris!!!

Although The Middle focuses on a white family, it too is a family sitcom based on the working class. In the article, Tim Gibson notes that Chris’s father works two jobs. Both of the Heck parents work multiple jobs to keep the family afloat. In one episode of Everybody Hates Chris. Chris asks for an allowance and his parents immediately turn him down. In The Middle, the youngest son brick asks his parents if they will buy him night vision goggles. They look at each other and Frankie replies, “you must be thinking of a different family”. The Heck’s economic struggle is a focal point of the show, much like it is on Everybody Hates Chris.

Everybody Hates Chris debuted before the economic crisis, so there was not as much of a demand for shows featuring working class families. Currently, there is a larger demand for shows depicting economically struggling characters, and there is a trend away from shows with wealthy characters. Shows like Shameless and Breaking Bad deal with the lengths that people will go to, to simply stay economically afloat. People want to see their problems reflected on the television screen, so that they do not feel so alone in their struggles.

Even though both shows deal with the hardships and strains that come with raising a family, they are warm and heartfelt at times. Ultimately, both programs show that it is worth it to have a family and that it is a deep and loving bond that cannot be broken by hard times. Both sitcoms are universal sitcoms that everyone can relate to, but they also deal with real issues. The readily accessible appeal of both these shows paired with the economic hardships that many people can relate to, allow these shows to be popular and successful with a large audience.

Todo mundo odeia o chris é o melhor seriado com certeza.

Aqui no brasil os episódios são bem repetitivos mas toda vez que assistimos rimos do mesmo jeito. o Brasil ama o chris!

Pingback: New Media Bias | Thoughts on digital culture from an accidental academic.