The Wii-volution will not be Televised:

The XNA-cution of a Business Model

by: Casey O’Donnell / Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute

In May of 2005, Nintendo announced the Revolution, a system designed to bring new modes of user interaction, maintaining backward compatibility with the GameCube, and leveraging Nintendo's back catalog of video game intellectual property (IP). Just under a year later the system was handed a new name, the Nintendo Wii, complete with Wii Remote (Wii-mote), weather channel (Wii-ther Channel), and personal avatar army (Mii's). There has been massive critical acclaim as well as lamblasting. Six months later and explosive demand for this new system, despite its technological lagging behind Microsoft's Xbox 360, or Sony's Playstation 3, has resulted in empty store shelves. But the latest wiz-bang hardware was never the point of the system, it was about revolutionizing the way we play games; and if demand, buzz, and developer excitement are any indication, Sony and Microsoft's Bastille is in trouble.

But, what if I told you that a much larger revolution was going on? What if I told you that despite the Wii's impressive new controls and user experience, that Microsoft was fundamentally changing the way video games get created? What if I told you that this change, if unanswered by Sony and Nintendo, who have built their empires on the way console games are currently made, will find themselves with consoles that require more effort to create games, and fewer developers experienced in developing games for their systems?

“In the 30 years of video game development, the art of making console games has been reserved for those with big projects, big budgets and the backing of big game labels. Now Microsoft Corp. is bringing this art to the masses with a revolutionary new set of tools, called XNA Game Studio Express, based on the XNA™ platform. XNA Game Studio Express will democratize game development by delivering the necessary tools to hobbyists, students, indie developers and studios alike to help them bring their creative game ideas to life while nurturing game development talent, collaboration and sharing that will benefit the entire industry.”[1]

While this press release is correct (though I quibble with the word “democracy”) that game development for consoles has largely followed one particular business model, it leaves out the historical record. Where did this model come from and why did Microsoft follow it for their own Xbox, only to now want a change of tune for the Xbox 360?

The answer lies largely at the feet of Nintendo, who was attempting to learn from the lessons taught by the crumbling tower of Atari in 1983. The primary lessons learned was, “No Custer's Last Revenge,” and “Piracy is bad.” Which meant that they needed to create a mechanism for protecting production rights. The answer was found in US Patent Number 4,799,635, “System for Determining Authenticity of an External Memory Used in an Information Processing Apparatus,” or more commonly the 10NES lockout chip.

Every mainstream console system released since the NES has contained a mechanism for protecting production rights. A business model carved in the silicon of console hardware. Let that sink in for a moment. When Greg Costikyan took the stage at the 2005 International Game Developer Association Rant Session at the Game Developers Conference, he raged against the machine that now represents the business model of the console industry:

“Nintendo is the company that brought us to this precipice. Nintendo established the business model under which we are crucified today. Nintendo said, 'pay us a royalty not on sales, but on manufacturing.' Nintendo said, 'we will decide what games we'll allow you to publish,' ostensibly to prevent another crash like that of 1983, but in reality to quash any innovation but their own. Iwata-san said he has the heart of the gamer, and my question is what poor bastard's chest did he carve it from?”

That isn't to say that game developers haven't had their piece in this as well. We've traded our freedoms to play with the latest and greatest hardware. New hardware always holds a kind of siren appeal for developers, luring us away into swirling whirlpools of new tools, new pipelines, and frequently the need to reinvent the way games get created.

This is of course coupled with the non-disclosure agreements (NDA's) that frequently accompany the licensing deals with publishers or console makers. Then you get your development hardware along with some basic run of the mill build tools and some documentation that typically does things the hard way, so you don't really have an idea of what a real game looks like for a given console, and you often only have access to a few closed “discussion” forums or email lists where other developers are so busy they don't respond, or when they do, answers often indicate that if you knew anything you should already know that. Which means that we reinvent the wheel and recreate all of our pipelines at each generational change of hardware, if our company manages to survive that long.

This is the real revolutionary power of Microsoft's XNA Game Studio Express. While Microsoft's interest in Open Source Software seems to be love-hate at best, I do believe that Microsoft has put their finger on a different kind of pulse. That is the pulse of millions of amateur, independent, international, student, and open source developers who've been dying to take a crack at developing games for console systems.

Oddly enough, this demographic could provide a needed boost in the area that game development has been lacking, institutional or industry learning. By and large companies have not gotten any better at making games over the last 30 years. We still end up scrambling and running around like chickens with our heads chopped off putting in 80+ hour weeks in the hope that whatever we attach to our necks works. Open Source developers have proven that their real knack is in the area of hardware abstraction and creating reusable API's that span hardware and software configurations. Their timelines can span multiple projects. You get group investment into a common code base. Sounds exactly like what we need. Take a look at the forums of GameDev.Net and you'll see hundreds of hungry amateur developers helping one another learn the in's and out's of game development, and posting useful code tidbits. Too bad we haven't been able to do something like this more broadly.

But we can now. All we have to do is sell our souls to Microsoft's C#, Windows Vista, and Direct X 10 API for this opportunity. All Microsoft gets out of it is an ability to disrupt the business model that has until recently kept them at the middle of the pack and gain the efforts of the hordes of developers itching to try their game development skills on a piece of next generation console hardware. Does it mean that they've given up control of distribution? Heck no. But there is a contest if you're interested.

So, Sony? Nintendo? The time has come for you to feel the winds of change. It's your game to lose, and your princess is going to be in another castle if you don't choose wisely. It's time to open things up a bit.

Notes

[1] Microsoft XNA Press Release

Image Credits:

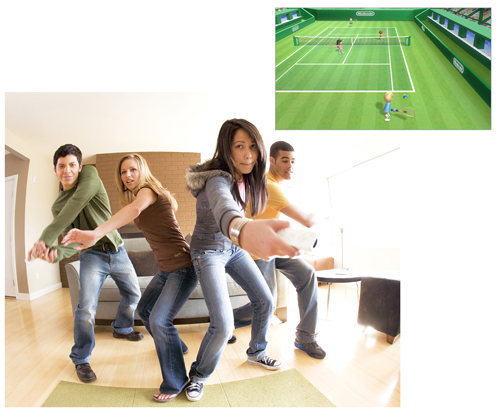

1. Wii Console

2. Wii Tennis

Please feel free to comment.

A very insightful and informative article. I know that the trend towards conglomerate control of entertainment intellectual property (IP) is nothing new…but I still feel quite conflicted about it. I understand that centralization of technology in the hands of companies that have sufficient capital to invest and reinvest in speculative ventures is one way that technology can advance so quickly. However, I cringe at the distribution of capital within that system, specifically that the “amateur, independent, international, student, and open source developers who’ve been dying to take a crack at developing games for console systems” who provide much of the creative IP don’t end up owning that property and only benefit to the extent that the corporation deems “competitive” in terms of compensation. Whether in this industry or other creative industries, it’s rare for “creative types” (the composers, the artists, the developers) to see substantial (or sometimes even livable) wages until they have some power within the system–some way to demand residuals, or some way to work their way up into management, i.e. overseeing the “creative types.” Call me cynical, but I can’t help but fear that Microsoft’s veneer of democratization is just another way to get a whole lot of creative labor for super cheap–so that the executives can reap the rewards in the marketplace.

compare industries

Though it might have its downfalls, making game developing a more “freelance” operation might help it. You can view this type of process like the music industry. You can create, compose, and present your music and if someone in a higher position thinks you’re on to something, you’re given an opportunity on a professional level. This makes the music industry more open to new, artistic, and original ideas that don’t necessarily follow the norms of all other present day forms. In the same way, this can benefit game developing and amateurs taking their shot at it.

This is a tough one…

Happy to see to folks make comments here. In many respects you’re both right. I think it’s a tough question.

Jean, you’re definitely right to point out that this sort of system is open to exploitation, and you’re right. Matt is also right that it’s a way to make your way into the industry. So the question is, how do you make it reciprocally useful?

While Matt is right that it opens doors to new ideas, I’m often frustrated by the game industry’s inability to fund innovation internally. I often use the statement, “Indy games are just too important to leave to indy developers.” It’s unfair for the industry to leave risk up to everyone else.

The other ironic piece related to the “exploitation” bit is that if these platforms were more open, developers would actually be contributing to the companies bottom lines. Instead they spend 50% of their time exploiting themselves so they can (crack) open up a system to further exploit themselves developing new things. The whole illegitimate aspect of homebrew just makes me confused.

My honest opinion (and if The Escapist Magazine will let me write the article for them…) is that one of the main reasons companies don’t want homebrew is because they don’t want emulators. They want to sell you the same game again. If more homebrew was focused on original development rather than emulation, it might be viewed as more legitimate.

I think the difference is really in that I hope that if there were more independent developers making games for these systems we might see more distribution of power. But right now, the urge by publishers to consolidate and the willingness of studio owners to sell undermines any kind of solidarity that could be gained by more players in the development community.

Pingback: New Media and Society Essay: Free/Open Game Development « Shambling Rambling Babbling

Pingback: The Price of “Closed” Hardware « Shambling Rambling Babbling