Don Knotts: Reluctant Sex Object

Sexual inadequacy is the default setting of many male comedians.1 Of course, there have always been the swaggering, abrasive jokers, but the truly winning comics are more often the pathetic losers who just can’t seem to get it on. Why do these types appeal? In the very prurient post-Code comedies of the 1950s and 60s, like That Touch of Mink (1962) and The Moon is Blue (1953), “seduction” is often a thinly coded euphemism for rape. In this context, the desexualized, man-child comics come as quite a relief; they seem to be the only ones not trying to force their way into their leading ladies’ pants. Indeed, as a child watching Martin-Lewis movies on TV, it was Jerry who appealed more to me, not simply because he was goofy and infantile but because Dean seemed to be “only after one thing,” as they used to say, while Jerry, in addition to being funny, was not a sexual predator.

In the film version of The Celluloid Closet (1995), a writer from the post-Code era calls films of the Doris Day ilk “DF pictures.” The “happy ending” of such romantic comedies wasn’t really the ringing of wedding bells that closed the films. It was the Delayed Fuck. It’s hardly a secret that many movies of this era were about having or not having sex, but it is wonderful and startling to hear the creators of such pictures lay it all on the line so explicitly. For some comedians, though, the delay was endless. In his numerous film and television roles, Don Knotts simply never made it to the “F.”2 Even as a pornographer in The Love God? (1969), he remains a virgin, though, in the end, he is tricked into thinking he has been deflowered.

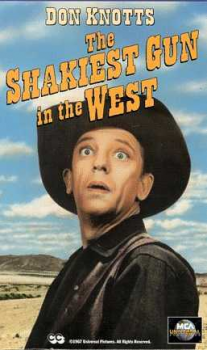

Knotts referred to his comic persona as “the nervous man,” a character who was, as the New York Times wrote shortly after his death in February 2006, “absolutely flappable.” At first glance, Knotts might seem to be a one-trick pony–a pair of scared, googly, bug-eyes attached to a pipe cleaner body. While it is true that Knotts did his eye-popping routine over and over again (and, I might add, it was funny each and every time), there was much more to Knotts’ performance than simply nervous energy in response to frightening situations. In fact, Knotts’ act was often based around his sexuality, the joke being that he had none, mainly because of his slight frame. As he stutters–shortly before fainting–to a buxom seductress in The Shakiest Gun in the West (1967), “I always thought I was too thin for marriage.” Knotts was, I believe, a walking repressive hypothesis, his skinny body a constant reminder that sex was not an option for him. In not being sexual, of course, Knotts was really about sex much of the time.

To fully understand the nature of Knotts as reluctant sex object, it is helpful to turn to the history of his development as a performer. Knotts’ mother was a born-again Christian; the fundamentalists of the Depression years were adamantly opposed to gambling, liquor, make-up, cigarettes, and, of course, Hollywood films. Luckily for Knotts, as he explains in his autobiography, his mother thought that the prohibition on films was a bunch of “hogwash,” and she often took her son to the movies.3 Though he found Laurel and Hardy films inspirational, he was also drawn to Edgar Bergen and Jack Benny on the radio, and as he trained himself in performance he soon turned to ventriloquism, using a dummy, “Danny,” handcrafted by a neighbor. (Danny looked much like Don, but with a stronger hairline.) Since he was underweight, to join the service during World War II Knotts had to sign a waiver in case basic training killed him. Having officially listed his profession as “ventriloquist,” he was soon reassigned to the U.S.O., where he and Danny performed in a show called “Stars and Gripes.” After the war, Knotts moved to New York City, where he couldn’t afford to attend Broadway shows, but he was able to get free tickets to radio shows, where he carefully studied and took notes on performance strategies. Eventually, he landed a role as a secondary character on a boy’s adventure radio show, which was a mild success for several years.

The films he attended with his mother may have inspired him to become an actor, but it was mastery of sound, not image, that initially kicked off Knotts’ career as a performer. Knotts’ formative years working with his voice, rather than his body, were crucial, for he never really learned to use his body fully as a comic tool. He was the most oral and facial comedian imaginable, though he did master a swagger, which I will discuss shortly, as well as a fake karate shtick.

The typical desexualized man-child comedian–Harry Langdon, Jerry Lewis, even SpongeBob SquarePants–has a dynamic or, at least, an interesting body.4 It is flabby or pliable or, more broadly, polymorphously perverse. Such excessive bodies are funny. But Knotts’ body was rarely pushed, pulled, prodded, or palpated. For the most part, his head was his only expressive bodily part; with his bulging eyes, pursed mouth, and popping neck veins, in fact, one might read Knotts’ head as a stand-in for the below-the-waste mechanics that he seemed unable to activate. Even when his body is “in action,” it does not fulfill comic expectations. When he finally makes it into space in The Reluctant Astronaut, for example, his zero gravity performance is more than a little underwhelming: He squirts some peanut butter out from a tube and floats about a bit.

The closest Knotts comes to a bravura physical feat is in The Shakiest Gun in the West, in which he plays a nervous Old West dentist “forced to switch from gums to guns.” In a sequence that is both an homage to and a departure from the W.C. Field classic, The Dentist, Knotts attempts to treat a female patient who refuses to open her mouth. Knotts finally notes, casually, “I’d like very much to see you socially sometime.” A pleased Miss Stephenson opens her mouth to answer, and Knotts inserts his fingers. In a textbook Freudian moment, the castrating Miss Stephenson immediately clamps down on Knott’s fingers. He yanks his fingers out, and the two get in a punching match, she striking the first blow. Somehow, the patient ends up standing, Knotts’ legs wrapped around her pelvis as she swings him about wildly. Her back against the wall, at one point, this resembles nothing so much as a reverse coitus, with Knotts as receptive vehicle and the patient as penetrator. Suddenly, oddly, the camera cuts away, a loud thud is heard, and, cut, Knotts is leaning over the knocked out patient performing his dental procedure. Though Knotts wins the scuffle, we don’t see the winning move. Did he really suddenly turn phallic and knock her cold? Or did she simply bump her own head? The Fields version of this encounter is, of course, quite different insofar as Fields acts as sadistic aggressor, pounding away at his resistant patient, whereas Knotts, though technically positioned as the one who wants to penetrate the mouth of Miss Stephenson, is visually presented as the penetrated party.5

The gender reversal ante is upped in the climactic scenes of Gun. Knotts has married a comely gunfighter who has no sexual interest in him, and his honeymoon has been infinitely deferred. After she is kidnapped by “injuns” (undeniably racist caricatures), Knotts infiltrates the camp and ends up dressed up like a “squaw,” in full redface. When a smitten Indian will not be deterred from pursuing Knotts, he retaliates by flirting with another Indian, placing the Indian’s hand on his knee. When the two enamored fellows get in a fight over him, Knotts slips away. He ends up in a shoot-out (still in drag), but the camera cuts away at the last minute. Knotts wins, but we don’t see it, and the anticlimactic effect is rather like the sequence with the cold-cocked dental patient. Knotts rides into town with the Indians in the end, still in drag (for no narrative reason), and is almost carried away by his would-be Indian lover. When he can’t get out of the man’s arms, he looks at his wife, shrugs, and nuzzles into the Indian’s neck. She punches out her rival, however, and drags Knotts off-camera, in a final, light-hearted, oddly Sapphic moment.

Knotts’ Emmy-winning performance in The Andy Griffith Show landed him the lead in The Incredible Mr. Limpet (1964), in which he is turned into an animated, Nazi U-boat fighting fish. This film, in turn, won him a contract with Universal, with whom he made The Ghost and Mr. Chicken (1965), The Reluctant Astronaut (1967), The Shakiest Gun in the West, The Love God?, and How to Frame a Figg (1971). Knotts claims that Figg bombed because by the early 70s the market for family films had bottomed out. On the other hand, The Love God? was doomed because Knotts had already made his name as a “clean” actor whose persistent problem was emasculation and (implicitly or explicitly) the inability to succeed with women–a scenario, of course, which was both clean and dirty at the same time. In The Love God? (rated M, for “mature audiences”) Knotts is tricked into becoming a pornographer. His backers set him up in a fancy penthouse, with tons of girls, studly capes and caps, and an enormous bed with scoreboard headboard. Though Knotts has no luck with his live-in ladies (and does not even try to score), the sexual content here was clearly over the top for viewers who expected a pseudo-desexualized Knotts. A few years later, Knotts would retaliate with a popular CBS TV special called The Don Knotts Nice Clean Decent Wholesome Hour.

Interestingly, Knotts may have actually been least desexualized on The Andy Griffith Show. It was only after he moved onto his film career, after five years on Andy Griffith, that he was suddenly denied sexual success across the board. Thus, at exactly the moment when films were getting more risqué and TV was supposedly clean, it was on TV that Knotts was allowed a degree of sexual proficiency. As Barney Fife on Andy Griffith, between break-ups and make-ups with girlfriend Thelma Lou, Knotts ended up in a number of make-out sessions (“smoochin’; parties,” as Andy says in “The Rivals” episode). Most shockingly–for a squeaky clean show in which “sugar on the jaw” (a kiss on the cheek) was construed as heavy-duty romance–in the “Barney on the Rebound” episode Andy walks in on Barney and Thelma Lou in the dark on a love seat. Barney makes a beeline for the couch while Thelma Lou flees the room, and then Andy turns on the light to find Barney, nonchalant, sipping a cup of coffee with his legs crossed (!), his hair wild, and his face covered with lipstick. Barney, for once, is extremely relaxed, as he casually explains that he and Thelma Lou have been “talking.” Leaving behind his nervous man routine, we see Knotts’; range here, and, implicitly, that it took a sexual release to drain him of his usual hopped-up style. The joke here is that while, on the one hand, the supposedly sexually unattractive Barney has actually seen some action he has, on the other hand, clearly been more ravaged than ravager. Even as he has succeeded he has failed, in masculinist terms, as he is sexual object, not subject.

Though Knotts relied mostly on his voice and facial expressions for comic effect, he did make some use of his body. In particular, he swaggered when he was feeling confident. On Andy Griffith he used the swagger when he felt (falsely) self-assured, and this swagger would carry over to his film performances, as well as, of course, his role as Mr. Furley, the would-be swinger of Three’s Company. In The Love God?, he gets pimped out in a variety of flashy outfits and flaunts his swagger, walking in place in a montage sequence, with pretty girls in matching outfits at his side, all against a variety of rear-screen projection backgrounds. (It is moments like these that make one question the need for films like Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery (1997). When the kitschy 1960s originals are so outrageous, why bother with parody?)

But Knotts more frequently signaled rare moments of confidence not with his whole body but only, more economically, with a smile and a back-and-forth swing of his head. Indeed, it would be hard to imagine a more “neck up” performer. Consider the scene in The Reluctant Astronaut when Knotts walks into a fancy NASA control room, a large floor waxer in hand. Buster Keaton would end up riding the device like a horse. Lucille Ball would end up hanging off the drapes, after they got sucked into the waxer. Jerry Lewis would end up using the irregular thump and whir of the waxer as a backbeat for one of his brilliant jazz pantomime sequences. And Don Knotts ends up…waxing the floor! There’s simply no room for physical pratfalls or prop comedy in the Knotts universe.

In fact, outside of the leg-wrapping sequence in Gun, The Ghost and Mr. Chicken is the only film in which Knotts engages his body from the neck down in any serious fashion, in three separate scenes: he falls down a coal shoot, flips into an elevator, and, having already pretended to know karate and having explained that his “whole body is a weapon,” hurls himself like a projectile at a villain. Unfortunately, these three physical moments are disappointing, as they are clearly performed by doubles. These are athletic stunts, not comic performances. Clearly, Knotts could not meet the challenge of physical comedy. But the point here is not that Knotts was a poor comedian–though there is certainly no doubt that he was a lesser talent than Ball, Keaton, or Lewis. Rather, I would argue that Knotts, so voice and face centered, so consistently presented as non-sexual in his film roles, simply could not be represented as an active body. Knotts the ventriloquist must himself be ventriloquized by a stuntman to be represented as a physical force.

When I mentioned to a friend that I was “busy watching Don Knotts” films, he quickly corrected me: “There are Jerry Lewis films; Don Knotts made movies.” There is something to this. Lewis, of course, was an “auteur,” his films “metacinematic in that they are heavily interspersed with quotations from other films, parodies of film genres, gags lifted from other films [and] self-quotation…”6 There is “a systematic deconstruction of comedy itself in Lewis' films.”7 This level of sophistication is clearly lacking from the Knotts oeuvre. Knotts never directed films, and, given a shot at producing his own TV variety show, he failed miserably because he simply couldn’t crank out the comedy fast enough, and he couldn’t manage the writing staff at maximum efficiency. If this was no Jerry Lewis, this was also no Sid Caesar. Still, Knotts should be of interest to us on several counts, even if he wasn’t “the best” comedian of his time.

First, comedy of the Cold War years was clearly strongest on television and in live performance with figures like Lenny Bruce. Tony Randall, Lewis, and Knotts were among the few performers of this era to successfully make the transition to film. The dominant film comedy of this era was romantic, featuring actors who could do comedy, like Jack Lemmon or Jimmy Stewart, rather than comedians per se. Though TV performers such as Ernie Kovacs, Jack Benny, and Milton Berle all took a swing at film, none ever forged a real career in the medium. Knotts not only pulled in reasonable box office from his Universal efforts but also went on to have a career in Disney films–sometimes in a major role, as in The Apple Dumpling Gang (1975) and, at other times, tragically underused, as in Gus (1976), in which he plays the coach of an ailing football team rescued by a field-goal kicking mule.

Second, Knotts reveals the potential of bodiless comedy. He was all face and voice, but he was always funny. Honestly, could you make it through a single episode of Andy Griffith without Barney Fife? The only contemporary performer who I think comes close to this level of non-corporeal facial performance is Steve Buscemi. In fact, in the Coen Brothers' segment of the omnibus film Paris je t’aime (2006), Buscemi seems to be channeling Knotts in his short comic vignette. The world is waiting for Buscemi-as-Knotts in a made-for-TV biopic!

And, finally, as I have tried to show, Knotts’; nervous man was a consistently sexually derailed persona. We might go so far as to label him “queer,” insofar as his sexuality was “abnormal,” seeming to endlessly swerve around the closure of intercourse. And he was queer in a rather unique way compared to other comedians of his generation. Man-child Jerry Lewis could transform into Buddy Love in The Nutty Professor (1963), whereas Knotts is unimaginable as sexual conqueror. Uncle Miltie was sometimes in drag, but was not a consistently queer persona, on or off stage.8 Tony Randall, Paul Lynde, and Jack Benny are in the running as queer comedians, but, were, arguably, more overtly gay in their representations. Knotts’ performance was queer, but not specifically gay. He didn’t seem to “really” desire men underneath it all. Instead, he seemed heterosexual yet also virtually incapable of sexuality, and it is in this very putative impossibility that I discern queerness. It was only funny for Knotts not to be sexy if he was linked to sex over and over again. On trial for obscenity in The Love God?, for example, Knotts (playing birdwatcher Abner Peacock) does a classic “slow burn” routine, as he is attacked by the Attorney General: “Look at his face! It is the face of a smut-monger. Look at his body, THIN, wasted away by the sin and debauchery of a life of unspeakable orgies and depravity…He does look innocent, until you look into his eyes. They’re the eyes of a man obsessed by sex… a man whose lust knows no bounds… The Marquis de Sade would have regarded Abner Peacock as a peer in his search for lechery.” As the Attorney General makes his case, the camera cuts between the apoplectic Knotts and the increasingly turned on middle-aged ladies in the courtroom. Between the lascivious female extras (many recognizable from Disney films) and the reference to the Marquis de Sade, it’s clear why this film went too far for 1969 viewers who came to theaters expecting a “family film.”

At least some viewers, though, might have thought the lecherous extras were right on track. As John Waters notes, “Don Knotts has always been a holy man in my life… When he was young, he was really my type.” In his recent one-man show, “This Filthy World,” Waters confessed that he regularly called Knotts’ agents about getting Knotts in his films, though, he warned them, Knotts would have to audition, and he fully intended to “use the casting couch.” Waters also regularly invited Knotts to be his date for movie premieres. Waters admitted that he suspected Knotts never received his messages, and it's hard to believe that Knotts had even heard of Waters. Knotts was finally the true object of sexual desire, but did he even know it? One imagines a poignant moment–a screwball version of Letter from an Unknown Woman (1948)–when one of his managers finally tells Knotts, “This John Waters keeps calling you for dates.” Don, in a Mr. Furley polyester pantsuit and cravat, springs to attention, widens his eyes, and asks, “Who the heck is Joan Waters?”

Image Credits:

1.

Don Knotts

2. Barney Fife

Please feel free to comment.

- “When comedian comedy mocks the heroic masculinity affirmed in serious drama, it often does so by creating a feminized, antiheroic male hero who appropriates the positive, anarchic, ‘feminine’ principles comedy affirms.” Kathleen Rowe, “Comedy, Melodrama and Gender: Theorizing the Genres of Laughter,” in Henry Jenkins and Kristine Brunovska Karnick, eds. Clasical Hollywood Comedy (New York: Routledge, 1995) 39-59. Quotation from p.45-46. [↩]

- I must confess that I have not seen every Don Knotts performance. If I’ve missed the key film or TV moment when Knotts finally lost his virginity, I hope that someone can correct me. [↩]

- Don Knotts with Robert Metz, Barney Fife and Other Characters I Have Known. New York: Berkley Boulevard Books, 1999. [↩]

- Heather Hendershot, “Nickelodeon’s Nautical Nonsense: The Intergenerational Appeal of SpongeBob SquarePants,” in Hendershot, ed. Nickelodeon Nation: The History, Politics and Economics of America’s Only TV Channel for Kids. New York: New York University Press, 2004. 182-208. [↩]

- Technically it is Knotts’ stunt-double who is positioned as sexual object here. More on this anon. [↩]

- Marcia Landy, “Jerry Agonistes: An Obscure Object of Critical Desire,” in Murray Pomerance, ed. Enfant Terrible! Jerry Lewis in American Film (New York: New York University Press, 2002) 59-73. Quotation from p.63. [↩]

- Dana Polan, “Being and Nuttiness: Jerry Lewis and the French” Journal of Popular Film and Television 12.1: 42-46. Quotation from p.46. [↩]

- Berle asserted his heterosexuality via “masculine” traits such as frequent cigar chomping, and, off camera, boasting (reportedly with reason) about the size of his manhood. See Jeff Kisseloff, The Box: An Oral History of Television, 1929-1961. New York: Penguin, 1997. [↩]

Buscemi in ‘Fargo’

The Steve Buscemi parallel is an interesting one, especially in he and Knotts being so face-centric in their performances. One might chart his character’s downfall in ‘Fargo’ according to the condition of his face which, in the film’s latter third, endures a both a gunshot wound and axe-chop. Like Knotts in ‘The Love God?’ it’s the insinuation of sexuality from such a homely creature that creates comedy–Buscemi’s suggestion to find some girls upon arrival to Minneapolis is shot down by his associate’s insistence on finding a pancake house instead. The (black) comedic tone shifts abruptly when Buscemi’s sexual impotence is made explicit later on with a prostitute, the act interrupted by Shep’s intruding and beating his naked, curled-up body. That scene, tragi-comic and pathetic like so many others in the film, is a great reminder that while actors like Buscemi are best framed from the neck up, there’s meaning to be made in manipulating everything below the neck as well.

Pingback: FlowTV | Don Knotts: Reluctant Sex Object