Buy Robot

The Who belt out “My Generation” as we swoop rollercoaster-like through the shiny innards of some machine. Superlatives flash on the screen, and the voiceover kicks in: “Introducing the NS-5, the world's first fully-automated domestic assistant. What will you do with yours? Get ready for the 'I' generation.”

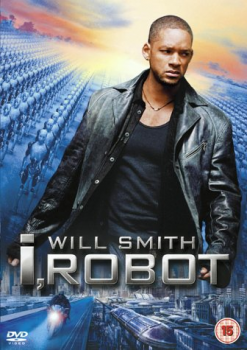

The advance promotion for Alex Proyas's 2004 Will Smith vehicle I, Robot never mentions the film. Neither does the website to which this teaser leads viewers. Instead visitors find a site modeled on automakers' sites, where one can see an explanation of the NS-5's features, read profiles of its designers and a history of its development, and customize a model whose image is then emailed for use as screen wallpaper.

Teasers for The Stepford Wives (2004) advertised robotic spouses. Ads for Resident Evil: Apocalypse (2004) pushed beauty products from the Umbrella Corporation. The Minority Report (2002) website includes a political advertisement endorsing the Precrime ballot initiative from the film.

This kind of film advertising reverses the practice of product placement. Instead of a real-world product appearing in the film's fictional milieu, a product from within that fictional world is projected into the quotidian world and treated as (mostly) real: packaged and marketed, but not delivered.

A number of films (e.g., The Blair Witch Project (1999), Artificial Intelligence: A.I. (2001), and Godsend (2004)) have used their websites to blur the boundaries between reality and fiction. I, Robot, in the relationship between the film itself and its promotional campaign, encapsulates this strange import/export business of product placement and projection.

Proyas's film tries to make a virtue of the oft-vilified practice of product placement. Abandoning subtlety, the film embraces its corporate underwriters, using the blatant appearance of a pair of Converse All-Stars as character development (the protagonist in our future world is a luddite, his apartment and clothing reflecting his refusal of modern conveniences), and using the appearance of a big-screen FedEx ad to contribute to the film's “realism” (“See, they still have package delivery in the future!”).

Given that the film's plot revolves around the impending release of a new and improved line of robot servitors, and the obligatory presumption that corporate greed motivates the murder that serves as the plot's initial engine, these overt product placements seem thematically consistent (though even a hint of ironic distance might be nice), and, to be fair, might contribute to the film's verisimilitude. The appearance of familiar corporate logos helps to tame the alien-ness of the science fiction setting. The FedEx Guy may be a FedEx It, but the logo is still recognizable, and so we know that what we're watching doesn't take place in a galaxy far, far away, but in our own near future (near enough that though FedEx has replaced its human workforce with automatons, it hasn't yet updated its brand image). That nearness makes any social commentary–on consumer culture perhaps–potentially more relevant.

The film's advance promotion, then, seems equally appropriate. If the film's world is expected to import real-world products, it's only fair that it gets to export one as well. Advertising the film's NS-5 robots functions narratively much like product placement. It blurs the boundaries between our experience and the film's world by adopting the stance that the NS-5 is real and available.

The commercial for Resident Evil: Apocalypse starts as a convincing mimic of an age-defying cosmetic commercial, but reveals its nature as a film advertisement. Neither the teaser nor the website for the NS-5 breaks the illusion. Both borrow heavily from the conventions of automobile advertising and the aesthetics of Apple's iMac promotion, the result of which is that the robots are far more convincing, more “realistic,” in the teaser and on the website than in the film.

This kind of advertising, this product projection, occupies a previously vacant spot in the continuum between the quotidian world and the fantastic settings of films. Product placement puts real brands into fictional worlds. Licensing can put fictional products into the real world (think Harry Potter's Bertie Bott's jelly beans), or nearly so–you can buy a replica light saber and hold it in your hands, but it won't cut much. Product projection occupies that liminal space between the two, providing the semblance of availability without being able to deliver.

Product projection, at least as practiced for I, Robot, gambles on transference of desire. If the ads for the NS-5 create an appetite for the product, it's a hunger that can't be satisfied by purchasing the robot. Instead viewers have to see the movie to get more of the NS-5, and so the practice is a kind of fantastic bait-and-switch in which consumers are drawn in by the promise of one product and then offered up a substitute. The teaser offers a personal domestic robot, perhaps the ultimate labor-saving device, the trailer reveals that the robot exists only as a nemesis for Will Smith (the real product here), and the film itself delivers a predictable science-fiction/action story with moderately convincing CGI effects.

With I, Robot, The Stepford Wives, Godsend, and Resident Evil: Apocalypse all employing some sort of product projection in their advertising, 2004 seems to have been some sort of breakthrough year for fantasy-to-reality export. Currently we see similar tactics being employed in the Oceanic Airlines and Dharma Initiative websites being used to give the ABC series Lost an increased sense of realism. The relatively small investment required to market online and the enormous potential of digital media to convincingly portray the unreal make it only logical that the mimicking of commercial promotional forms to hawk fictional wares has become a potent tool for the creation of verisimilitude. To sell is to be.

Image Credits:

4. Milla Jovovich in Resident Evil: Apocalypse

Please feel free to comment.

The age of cynicism?

I must admit that I am totally fascinated by virtual advertising, in which such complex ad campaigns only indirectly sell a product, and don’t actually sell that which they are created to pretend to sell. My biggest concern (perhaps not quite the right word) is that these ads have the potential to perpetuate cynicism in an age when many people already do not trust advertising. I’m not saying that we should trust advertising–however at some level I wonder if we shouldn’t be able to trust that at least an ad sells something that exists.

Or maybe I’m looking at this upside down, and we should praise these faux ads for pointing out what we all should know already: that advertising is inherently deceptive. And maybe it’s more “fun” when we can see through the deception, rather than feel liked we’re just plain being duped for no other reason than to sell a product that can’t live up to its advertising? At least with fake ads we know all along that we won’t actually get what’s promised?

I am extremely impressed together with your writing abilities as smartly with the structure to your blog. Is this a paid subject matter or did you customize it your self? Either way keep up the nice quality writing, it’s uncommon to look a nice weblog like this one nowadays.

Great article! This is the kind of info that are supposed to be shared across the internet.

Shame on Google for now not positioning this post upper!

Come on over and talk over with my site . Thank you =)