Hysterical Horowitz and The Culture of Television

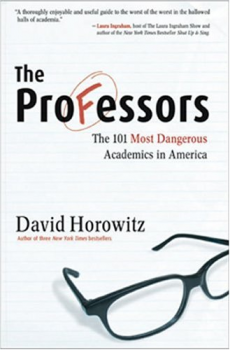

When the editors of Flow invited me to write the guest column for the inaugural issue of volume 4, I enthusiastically agreed. I saw it as an opportunity to take another light-hearted look at some aspect of our media culture. But I'm afraid this column is going to be neither clever nor funny despite the fact that its subject matter is hysterical. When people hear the word “hysterical” today, they often associate it with uncontrollable laughter. And I must admit that when I first picked up David Horowitz's new book, The Professors: The 101 Most Dangerous Academics in America, and began to page through it, I couldn't stop laughing. Now, that would scarcely be worth stating if the book was intended to be funny. I assure you, it's not. On the contrary, it's “hysterical” in the traditional, dictionary sense of the term: “behavior exhibiting overwhelming or unmanageable fear or emotional excess.”

Before I go any further, let me briefly describe this book for those readers fortunate enough not to have seen or heard about it yet. The Professors is a (black)list and brief biography of 101 left-leaning professors in the U.S., though the book refers to them as “radicals.” Now if books could crap their pants in fear, this one would be shitting itself by the inside flap, which barks, “Coming to a Campus Near You: Terrorists, racists, and communists–you know them as The Professors. … Today's radical academics aren't the exception — they're legion. And far from being harmless, they spew violent anti-Americanism, preach anti-Semitism, and cheer on the killing of America soldiers and civilians — all the while collecting tax dollars and tuition fees to indoctrinate our children.” As I said, hysterical!!!

The book goes on to “imply” — it doesn't squander its precious pages employing something academics call “logic” — that award winning teachers and scholars the likes of bell hooks, Fredric Jameson, Angela Davis, Howard Zinn, Dana Cloud, Noam Chomsky, and Robert McChesney are indoctrinating students with “evil” liberal ideology and an utter disregard for the truth. As near as I can discern, Horowitz's hysterical rhetoric is fueled by the fear that an immense army of “radicals” is teaching students what to think, rather than how to think (p. xxvi). I, too, think that educators have a professional responsibility to teach students how to think, so that they can form their own opinions and judgments on matters of social importance. But I also think that educators have a responsibility to teach students how to think well (i.e., rationally, soundly, and logically). That said, students should read Horowitz's book. More specifically, they should read it in an introductory argumentation class as an exemplar of fallacious reasoning.

My aim in this column is not to defend the professors on Mr. Horowitz's list. My sense is that most, perhaps even all, of them don't need to be defended. Instead, I'm going to take a few minutes and illustrate how The Professors can productively be used to teach college students the fundamentals of faulty reasoning. Let's start with a definition — a common tool for constructing arguments and something virtually absent from The Professors. “A fallacy,” according to William Foster (1917), “is an error in the reasoning process. It is an unwarranted transition from one proposition to another” (p. 190). You may have noticed that my definition comes from an expert — something else conspicuously absent throughout much of the book. If you've read The Professors, then you recognize that there is simply no way I could recount all of its logical fallacies. To quote a book I recently read, they “aren't the exception — they're legion.” So, instead, I'm going to highlight four of my favorite fallacies:

1. Hasty generalization – this fallacy arises when a broad conclusion is drawn from too small of a sample, from an unrepresentative sample, or ignores key exceptions (Foster, p. 193). For instance, if I concluded that Mr. Horowitz is simple-minded based upon his “logic” in The Professors, I would be making a hasty generalization, as I have not read enough of his work yet to properly draw that conclusion. For all I know, The Professors is an exception to his otherwise fine thinking. The central, if implied, claim of Horowitz's book is that American Universities are under siege from 30,000 radical professors, who are using their authority to indoctrinate students with leftist ideology (p. xlv). His “data” is drawn from biographical sketches (about 2-3 pages each) of 101 professors that he helped to edit and write (p. xlvi). Even if all of the professors Horowitz identifies actually do indoctrinate their students (a highly dubious assumption), they would constitute only about 3% of the total number of so-called “radical professors” in the U.S. — this according to Horowitz's own numbers (p. xivi). But since he selected faculty that he specifically considers “the 101 most dangerous,” they are by definition not representative. You can't study the “most colorful” fish in the sea, and then reasonably conclude that all fish are equally colorful. That's just plain stupid.

2. Ad hominem – this fallacy occurs when one attacks a person's character rather than his or her argument (Foster, p. 204). If, after reading his book, I were to proclaim, “Mr. Horowitz is a lunatic, who should be institutionalized to protect the public,” I would be committing the fallacy of ad hominem. Although most of his book is ad hominem, my favorite instance is the repeated character assassination of those professors who have raised questions about the war in Iraq or attempted to understand the motivations of the 9/11 terrorists. To even ask these “questions” gets one branded “anti-American” in The Professors (pp. 3, 7, 75, 110, 164, 178, and 189). Rather than debate the “justness” of U.S. foreign policy, the Iraq War, or even war in general (Horowitz is critical of the entire field of Peace Studies [p. xxv]), Horowitz lobs verbal grenades at the character of these distinguished professors. I suspect this is because if he were to engage them rationally on these issues, he would find himself on the losing side.

3. Ad populum – this fallacy results when one appeals to tradition or prejudice rather than to reason (Foster, p. 205). Were I to imply, without offering evidence, that The Professors is just your typical right-wing, extremist, fear-mongering, irrational malediction that would be ad populum. Likewise, when Horowitz lumps a tremendously diverse array of academics under the label “radical,” it is calculated to appeal to his readers' prejudices. Rhetorically, it works to erase their vast differences and to make them “guilty” by association … with each other (they are, after all, on the same list) and activist organizations. The book further appeals to readers' prejudices by “outing” various professors as Marxists, communists, socialists, feminists, and queer theorists (pp. 13, 23, 61, 64, 92, 120, 160, 169, 177, 180, 186, 217, 293, 308, 323, 329, and 346). Given that Horowitz does not define these perspectives or clearly articulate his objections to them, it would appear that they are deployed specifically to evoke fear, rather than as part of a rational argument. As the book is “A Main Selection of the Conservative Book Club,” such fear appeals may be effective, if fallacious.

4. Shifting ground – this fallacy involves unreflectively changing the proposition initially offered (Foster, p. 208). Should I posit that Mr. Horowitz loves poor reasoning, but only demonstrate that his book is poorly reasoned I have shifted ground. Horowitz is constantly shifting ground in The Professors. He claims that his objection is not to professors' biases, but to their imposition of those biases on students (p. xxvi), and yet example after example in the book is draw from professors' statements outside of the classroom. He repeatedly quotes their scholarship, public remarks, and other non-classroom sources to illustrate his point. But these things don't illustrate his point; they silently and unreflectively shift the ground of argument, fostering the false impression of evidence.

I could go on and on, as The Professors is filled with logical contradictions, bold unsupported claims, and flat out non-sequitors. But what's my point and what does it have to do with our media culture? My point is that in a society flooded with information, it is more vital than ever that we teach students to critically assess and evaluate that information. If it is built upon faulty reasoning, then we should judge it accordingly. Poorly reasoned, hyperbolic rhetoric such as The Professors undermines healthy public debate. Let me close with a hypothesis of my own, for which I will proffer at least some initial evidence. Feel free to add your own. Thesis: David Horowitz's The Professors mirrors the decline of rational public discourse often attributed to television culture (see Hart; Postman). Argument by analogy: Like television, it is little more than spectacle and tabloid, a distraction from the truly significant social and political issues that deserve our sustained attention. Like television, it is a character driven fiction, not a rational expository argument. Like television, it privileges superficiality over substance, and surface over depth. Like television, it is entertainment, not scholarship.

In The Sound Bite Society, Jeffrey Scheuer argues that television is increasingly altering the very form of political discourse today (p. 9). The rise of sound bites and image politics, he further contends, serves the rhetorical and ideological interests of the Right. Since their messages tend to view the world in simple, absolutist, and binary ways, they are particularly well suited to the new fragmented, electronic landscape. The Republican majorities in the House and Senate, the majority of state governorships, and the occupation of the White House would all seem to support Scheuer's claim and to suggest that if there is a growing ideological hegemony in the U.S., it is not, as Horowitz hysterically decries, coming from the Left.

Works Cited:

Foster, W. (1917). Argumentation and debating (rev. ed.). Cambridge, MA: The Riverside Press.

Hart, R. (1994). Seducing America: How television charms the modern voter. New York: Oxford University Press.

Postman, N. (1984). Amusing ourselves to death: Public discourse in the Age of show business. New York: Viking.

Scheuer, J. (2001). The sound bite society: How television helps the right and hurts the left. New York: Routledge.

Hysterical Rhetoric in the Guise of Argument Cited:

Horowitz, D. (2006). The professors: The 101 most dangerous academics in America. Washington, DC: Regnery Publishing, Inc.

Image Credits:

Please feel free to comment.

Ott’s Fallacy

This article does a fine job of pointing out some of the many problems with Horowitz’s brand of “scholarship,” which might be slightly more difficult than shooting fish in a barrel. But then it contradicts its own logical critique in the final two paragraphs.

To blame television for broadsides like Horowitz’s is Shifting Ground, using a careful account of his argumentation to lateral into a poorly substantiated condemnation of TV. It is a Hasty Generalization, attempting to sum up an entire medium that offers a huge range of programming, genres, and styles using broad strokes like “spectacle and tabloid” and “character driven fiction” – not to say those elements are not prevalent on the medium, but they cannot stand-in for the medium as a whole. It is Ad Populum, tapping into a broad rhetoric of “blame the media” without substantiating such claims – and appealing to “experts” who use similar shoddy argumentation. It also begs a central question: if Horowitz exhibits “television logic” (whatever that means), why does he do it in book form? Should we condemn the medium of the book for allowing such diatribes?

I certainly believe that certain trends in TV have had negative impacts on political discourse, but to blame the entire medium is to use the blunt weaponry of demogogues like Horowitz. As a television studies website that seeks to bring academic voices outside the academy, I hope we can look at television with more historical specificity and precision. If we cannot, then what are we adding to the public discourse?

Soundbite Culture

This is the kind of book that is designed to get “profiled” on Hardball. I think what is meant here by TV logic is a) particularly post-network (see cable + flipper = need for “attention grabbers”) and b) in a long tradition of American anti-intellectualism. For example, whenever I fly I look through the book section of whatever airport I am in and pick up the latest political/business book and it always strikes me that these things are written in a way that a producer for a show (typically someone with a BA) can “get it” quickly and then schedule that guest. If you want to move units you need to write in a style that seems to leave nuance in the dust and instead offers a reader a convenient set of binary oppositions that stand in lieu of an in depth argument.

Now, I guess this is something that we are trained NOT to do and something we hope our students understand is poor writing/thinking — or at least should. But I can’t get over the thought that I have seen Horowitz on TV at least 20 times more than all of the above mentioned professors combined. Yes, he is better funded. But he does not have to write in a nuanced manner for peers who expect, ahem, an attempt at finding the truth. For Horowitz and his audience the truth, with all of its nuances, is inconvenient. One has political aims and the other is worried that us scholars can’t get our argument out in a digestible manner before the channel gets changed.

That said, I do think that we need to understand that layer of TV production that feels it really needs those who are thoughtful communicators. In other words, Horowitz is a crap scholar, but is a pretty decent communicator because he understands what at least one element of his audience wants and needs: words that summarize rather than explain. It would be great if we could expect someone on CNN to give us a large chunk of time to communicate, but they won’t nor can they. If we want to hold a forum in a culture that validates soundbites, can’t we do some of that as well as do solid scholarship? Rather trying to explain every aspect of our argument, could we find a way to offer audience tempting words rather than boring lectures. I mean, I go to conferences all the time and I find it is the rare academic who is a truly effective communicator, myself included. It is a skill and one worth honing. Indeed, it’s worse when you see academics on TV. Here is a medium in which we need to understand that their audience often only wants to be tempted to go deeper and, if they do, they may do so. And yes, we don’t have Regnery on our side, but we do have public libraries, many of whom will stock our titles (I know, I have seen many of my peers books at my local branch). But let’s be honest as well: we may complain about living in a soundbite culture, but rather than simply complain (complain all we want it will most likely continue to exist) or we can think of soundbites as an effective tactic and one we need to learn how to better utilize.

A half-good analysis

i agree with the previous post that a well-aimed critique goes seriously astray in its closing salvo. Horotwitz sounds like a prize prat (and a dangerous one too), but this is not say that we must accept all what the ‘professors’ say, without finding flaws. I can remember, for example, Hart expounding his theories (at a media literacy conference in North Carolina) about the negative effects TV had on civility and political awareness in the USA. He claimed that ‘the media’ (TV in particular was generating tremendous cynicism about the ‘three pillars’ of American life (military, church and government. My response, as a non-American (aka ‘alien’)was that Americans needed to be even more cynical about institutions, and it was great if the media was indeed leading them in this direction.

I presume there is a counter collection, of “The 100 Most Dangerous Right-Wing Lunatics in America”?

Mittel’s Mis-takes

Jason might have a point about fallacies in Brian Otts article if Ott HAD blamed TV for a ‘the decline of rational discourse’ exhibitede by Horowitz’ hysterical ‘book’. Jason may feel an blame-it-on-TV proposition lurks implicitly between the lines of Ott’s writing. But, what Ott actually says is that the ‘decline of rational public discourse’ displayed by Horowitz is similar to pathologies OTHER PEOPLE have attributed to TELEVISON CULTURE.

Two points here.

First ‘television culture’ is not the medium itself, but would address the way it has come to be used within broad common practices. This may have nothing to do with the television medium itself. Rather, some third factor (or an overdeterming array of factors) may be making both political discourse and televisual discourse getting a case of the stupids.

Second, one can refer to something as a means of explaining one’s concepts without asserting that that something is true. For example, though, I might say that the illumination provided by an essay in FLOW mirrors the ispiration attributed to premies who have received The Knowledge from Guru Mahara Ji… without asking anyone to believe any of that mystical bs, or denegrating FLOW on the other hand. I have actually said the things are comparable in any way, only that the way people think about one thing may provide a useful model for thinging about something else that could be very very different.

Moving on, while Ott does not make any actual causal claims about TV whatsoever, he does make a series of attributions about TV which could be seen to be pejorative.TV, he says, is little more than spectacle, a distraction from truly significant social and political issues, a character driven fiction not a rational expository argument; it privileges superficiality over substance, and surface over depth; it is entertainment, not scholarship.

Some of these claims (re: rational argument & scholarship)are so obvious as to be trivial. Others are hardly extreme: to say that TV privileges surface ov er depth is not to say there is never any depth there. And a claim that TV privileges depth over surface would be, well, kinda silly. It seems to me this leaves Ott with only one claim that is highly arguable: that TV is little more than spectacle. TV is certainly has no shortage of empty spectacle, but in its multi-channel plenitude and polysemy, TV contains a LOT more than spectacle. A primary example for me would be The Apprentice, a weekly lesson in how race class and gender function in late capitalism.

Obvious, plausible, or overtstated, Ott’s theses are still descriptive. They don’t say that TV causes anything or is caused by anything just that it is like something.

It strikes me that Ott may have been trying to be very linguistically precise, in contrast to Horowiz intemperate jabs, in carefully limiting his critique of TV, and indicating that any depper theory being offered is done so suggestively, as food for thought, not the revealed truth that is the mode of right wing harrangues. And while historical specificity and precision are important elements of scholaship, so are big often wild and overreaching theoretical ideas that stir up our mental pots.

To be historically specifc, this line of thought reminds me (though I am sure this not Jason’s intent) of the moment in the 1980s when the powers that be in the Comm Arts department at UW-Madison decided there was too much ‘grand theory’ in media studies, and that what the field needed was history, precision and specificity (you know, like the historicism, formalism and move toward cognitive science in Bordwellian film studies), and all the TV scholars, who were all junior faculty, got run out of the program. Then a few years later, the University was able to land John Fiske, and he was prominent and established enough that the TV people got more or less left alone. However, there was a time there where the kind of critique Jason employed here would have been used to push him to exclude anything vaguely resembling what we would now identify as ‘Fiskean’ from his dissertation.

Horowitz, Adorno, and Enlightenment

I’m sure I’m over-simplifying here (not least because I’m setting politics aside here. There are other interesting parts of this story, after all), but I’m kind of amused yet worried by a strain of implied logic behind this book (and particularly its title … which Horowitz has said in interviews was a thing the marketing people came up with … but he signed off on it, so i feel happy in continuing):1. For a professor to be “dangerous” is to assume they have particular (“evil”) powers of persuasion over their students.2. which is to further assume that the students are vulnerable, and quite weak-minded (ie: this is a hypodermic needle model of teaching effects)3. but Horowitz often talks of how impressed he is with the resilience of some conservative students against such “brainwashing,” meaning that clearly these profs aren’t “dangerous” to all4. which means they’re dangerous to weak-minded/dumber students5. hence, this book would seem to be aimed at parents of dumb, peon-like, weak-minded children (which, dare I say, one would hope wouldn’t be accepted to the lofty heights of MIT, Columbia, and other common homes for “dangerous” profs in the first place)6. and it effectively declares that a large number of students are such dumb hunks of stupid.

I am very disturbed by particularly this last point. And it smells very familiar — we’re back to a wholly dubious notion of third person effects: “that show had absolutely no effect on me … but I’m very worried about that guy over there.” Horowitz and many of his key allies are so very condescending, then, to today’s youth when they talk of professors in such terms. By all means, I hope to have *some* form of effect on my students, but I’m under no illusion that they’re becoming little Jonathan Grays.

I wonder, then, how Horowitz would feel to know that he shares some very key ideas of contemporary society with renowned Marxist Theodor Adorno?

The Proof is in the Pudding

These comments by “alleged” readers of Horowitz’s book, are really the proof that he has a legitimate claim to liberal bias.

Sure, I’ll Bite

What? I’d love K.Painter to explain to me how one column and 5 responses (a few of which don’t even really discuss Horowitz’s claims of bias) equate to “proof” that our universities are biased. How does this follow logically, in any way shape or form? First, since when can we make quantitative claims about the American academy based on such small numbers (even smaller than 101)? But over and beyond that, how does Painter presume to know that the supposed “liberal”-ness of these posts (not even at all obvious in a couple of them) indicates bias at their *teaching* level? Is Painter’s point that merely having an opinion and expressing it is proof of “bias”? Or maybe liberals just shouldn’t be allowed to speak if holding any position of power or influence?

Here’s the Puddin’

Please do expand on your comment K. Painter.