Trading Races: Black. White. on the FX Network

Black. White. is a six-week social and televisual experiment in which two families, one Black one white, attempt to experience what it is like as members of a different race. It is currently airing on the FX Network, with the last two episodes scheduled for April 5 and 12, 2006. It is produced by Academy Award-nominated and Emmy Award-winning documentarian, R.J. Cutler, and by rapper and actor, Ice Cube, who sings the program’s theme song (he also wrote the incendiary songs, “Black Korea,” and “F*** tha Police” when he was a member of N.W.A.). The producers state that the program is intended to expose the subtleties of racism, while at the same time, it doesn’t “aspire to say definitive things about race.”1

As I write about in my book on racialized servants on television, in approaching the topic of ‘the representation of race’ we are, essentially, talking about the representation of race relations2. Similarly, in this reality television set-up — one that doesn’t hide its expectation that things will heat up when you put these people into a house together — we witness interactions and hear statements made that are not ‘about race’ per se, but about the ramifications of being racialized. Such ramifications, of course, are confined and contrived within the context of a six-week Reality TV series involving individuals willing (and wanting) to be on television. Nonetheless, the program offers insights into racial discourse. Moreover, as one reviewer wrote: “… it’s not what happens to the folks on this show that is so revealing. It’s what goes on in our own minds as we watch and listen to them try to navigate the shoals of racial differences.”3

What Black. White. serves to do is to engage in and reveal the struggle of defining ‘racism’ in a post-Civil Rights era. The six participants/characters in this program offer the idea that there are at least six different ways to see — or not see — racism in American culture. And perhaps inevitably, in the mode of character identification, viewers find themselves adhering to (or abhorring) a particular political/personal view on the meaning of racism.

The first, and perhaps most prominently featured character is Carmen Wurgel, whose parents participated in the Civil Rights Movement and whose white liberalism is palpable. Her passion to “understand the Black experience” is earnest, and yet she cries often for herself when she feels her intentions have been misunderstood, for example, when she calls a young Black woman in praise: “a beautiful black creature” and people are seriously offended. Her counterpart — and if you study the publicity, you’ll see the visual and thematic mirroring of mother, father, and child in the two families4 — is Renee Sparks, a middle-class woman from Atlanta. Her general disposition is that of incredulous mother, for example, when her teen-aged son buys a $150 watch and her disciplining lecture is heard throughout the house. Renee is also incredulous as a white woman, when she meets a young white man who says that he washes his hands after shaking a Black person’s hand. And she is incredulous at some of the things Carmen says who thinks she is connecting with Black culture when she uses the phrase, “Yo bi—” with the dialect coach.

Carmen’s emotional enthusiasm is matched by Renee’s cautious level-headedness, though they are both shocked at what they learn. Carmen’s realization that people will turn away from, doubt, or reject her because of “her beingness” (when she is in blackface) is perhaps overwrought at first, but it is heartfelt. What Renee learns about the discourse of racism in 2006 is that her son, Nick, is not bothered by “the N-word.” But when it is uttered among a group of white kids and Nick says it’s okay, a sad, uncomfortable look in his eyes betrays the nonchalant façade.

Brian Sparks and Bruno Marcotulli were cast undoubtedly for their diametrically opposed views on racism: “You see what you want to see,” Bruno says, to which Brian responds, “And you don’t see what you don’t want to see.” It’s as simple and complex as that. When Brian and Bruno walk down a sidewalk together, both as Black men, a group of white women move aside which Brian interprets as fear or distaste and which Bruno interprets as a courtesy. Despite the frustrated efforts on Brian’s part, and in spite of the premise of the program to have people “trade races” and swap perspectives, Bruno is not convinced that he is treated any differently — that life is any different — as a Black man. Bruno clings to his belief about being optimistic and “moving on,” and that prejudice exists if you look for it. His position is met with the most opposition from Carmen, who remarks after they go to a Country-Western lounge as a Black couple that Bruno essentially acts like a white man while in blackface. So the question remains, is a white person in blackface really experiencing what it is to be Black? Likewise, we learn more about what it is to be white from the white characters, not necessarily from the Black characters when they go out as whites. Nevertheless, it is through this experience — of wearing/bearing the costume of another race, of coming back to the house to talk about it, and of showing it on television — that meanings of race and racism are discussed and disclosed.

While Brian works deliberately to articulate his experience of being Black, illustrated by how he is treated more hospitably and less suspiciously as a white man, Bruno is a racism-denier. My definition of a racism-denier is not a person who denies that it exists, but rather, who believes that racism does not exist in his or her world. In this regard, the young Black man and the late-40s white man share some similar ideas about racism in America.

Nick Sparks’ parents are baffled and disheartened at their son’s apparent lack of awareness. Nick expresses he doesn’t really understand why they are doing this, and moreover, he states that doesn’t think the store clerk watches him because he is Black, nor does he “pay attention to things like that.” Rose Bloomfield, however, is rather sensitive to race and racial politics, perhaps because she is a white teenager from Santa Monica. On one hand, as teens schooled on Eminem and Tiger Woods, “race is not an issue,” and on the other hand, racial mixing and crossing cultural boundaries have become a conscious practice in popular teen culture (in music, fashion, slang). Rose and Nick represent the next generation in race relations. As individuals, and at least in the context of this situation, they get along well. Rose faces her insecurities as a privileged white person and Nick’s ambivalence about school and “his future” is drawn out a bit. The two talk with each other, appreciate and learn from one another, and are able to form an alliance. This is heartening.

Still, there are shortcomings, namely, the program is noncommittal and there isn’t a strong enough frame around what happens in the show. In terms of its structure, the selection of Black or white “experiences” (going to a Black church, attending etiquette classes in Bel Air) are over-determined and remain loose if not random; and they are not tied well into a narrative or set of narratives. This looseness, perhaps part of the reality-documentary directive and certainly as part of television’s polysemic nature, leaves the social/televisual experiment hanging and the point(s) about today’s racial dynamics unclear. Furthermore, having received skeptical advance press as “a Fox show,” it is notable that Black. White. airs on the FX Network, and late at night. (It is also available through pay-per-view, marking it as exceptional and/or forbidden.) The boldness in the “broadcast” is actually only being narrowcast. We have to wonder: why exactly has the program been considered so ‘controversial,’ and by whom?

The program indicates that race matters, and that it doesn’t matter, depending on one’s personal perspective. While different perspectives are shown, do the participants really see the world through different eyes — and for that matter, do the viewers? Halfway through the series, some of the characters are beginning to see the world with a changed perspective through their own eyes, while walking down the streets of various L.A. neighborhoods in a different skin color. And at this point in the program, a “plot twist” as arisen: Will Carmen and Bruno stay together in light of Bruno’s inability to, as Carmen says, have compassion. Compassion is a form of sympathy, of “feeling with.” Empathy is defined as “feeling into,” it is the ability to not only detect what others feel but also to experience that emotion yourself. It seems that in order for this experiment/experience to work, a person – whether a participant in the show, or a viewer of it – needs to develop empathy, to experience the feelings of another person.

Black. White. offers glimpses of breakthroughs in communication (Rose-Nick), as well as cultural impasses (Bruno-Brian), and moments of empathy (Carmen-Renee). Such set-ups may be generational and gendered, and they are certainly framed by genre. Reality television combines the seriousness of documentary with the sensationalism of “trash television.” This generic form enables race to be represented — to be representable. The cutting edge make-up techniques also make this program possible. Cutler states that Black. White. is not “some kind of make-up driven freak show” nor was he looking for “cheap conflict.” And while some critics say cosmetology is its most impressive feat, I disagree. What this program achieves is to get people talking about race in an age when they just don’t want to do it anymore.

Today’s discourse on race focuses on the debate about perceptions of racism, especially in a “post-race” era. This is “the era of Oprah Winfrey5 and Barack Obama6,” and of post-/anti-affirmative action. Depending on your personal politics, Oprah has risen to the top of the media world as an African American woman despite being Black or no matter being Black or white. While the new FX series defers to its characters and doesn’t quite shape a clear narrative about race relations, it does not promote a “color-blind” approach. After all, black and white are colors — especially on TV.

Notes

1 Black. White. on MSNBC. 27 Feb. 2006.

2 L.S. Kim, Maid in Color: Race Relations on and through American Television.

3 Nancy deWolf Smith, Wall Street Journal; Black. White. on Metacritic.

4 Bruno Marcotulli is actually Carmen’s boyfriend, and he’s also a part-time actor.

5 Incidentally, Oprah hosted the cast from Black. White. on an episode in which she also entered “the Race Machine” to see what she would look like/feel like as a white person, and Asian person, etc.) See:

“Trading Races”.

6 Clarence Page, “Trading races drama: Can we ever get out of the skin we were born in?” Chicago Tribune, 12 March 2006.

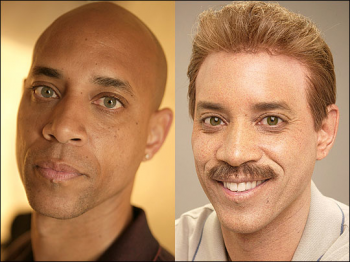

Image Credits:

1. Families Swap Race in Black. White on MSNBC

Please feel free to comment.

shades of gray and exnomination

A nicely nuanced look at the implications and shortcomings of a project largely intended to mark race relations as ‘gray’ in a post-Civil Rights era. Black.White definitely suggests that color blindness is neither an effective strategy nor a reality, but it seems equally invested in showing the world through a multi-perspectival lens that inevitably seems to reify difference. Bruno is,arguably, the series villain not because he fails to see racism, as much as for his denial of the Black experience as different from his own. By the same token, Rose is repeatedly pointed to as the most insightful white character (legitimated through the praise heaped on her by both Brian and Renee), but she is also the character most invested in reifying difference through alarmingly essentialist discouses of authenticity [though to hers and the producers credit, they do show her getting shot down for such assumptions and attempting to understand her misconceptions].

To some extent, the series is less about ‘race relations’ (though I agree with L.S. Kim’s point that inevitably this underlies all racialized interactions), than it is about learning that Black people experience the world differently than White people (a point driven home by the the non-parallel family experiences, whereby Bruno, Carmen, and Rose are repeatedly sent into unfamiliar terrains [the black poetry club, the church] or to familiar spaces wearing a different shade of skin [the dance hall], while Brian and Renee’s story has largely centered around thier efforts to teach Nick to better understand the Black experience as rooted in a history of oppression, racism, and suspicion).

While I think the show does offer occasionally insighful throw away moments that recognize how racism has changed in the post-Civil Rights era into something less overt, more institutionally-rooted in unequal opportunities for economic advancement and consumer pleasure, the show also largely fails to make whiteness more visible. Renee states in the first episode that she already knows how to act White – to some extent calling attention to the need for minorities to understand the dominant in ways that the dominant doesn’t have to ever understand itself – a privilege left unaddressed by the program – but it also inevitably naturalizes whiteness as a an easily identifiable category that all white people, and some non-whites can access at will, without ever having to investigate its make-up. Yes, the show admits, whiteness exists and it has power and privilege, but how performance and erasure play parts in maintaining power are still left invisible.

Black and whites’ soap opera

I have to point out three things about “Black and White”. First of all, I have to say that I was never fooled by the makeup. Despite the high tech wizardry, trading races on “Black and White” appear to me as the show unsuccessful attempt to stage an April fool joke on the audience. In real life, there are many ways to recognize race besides pigmentation. Thus, reducing race to skin color in itself is a very lazy premise for a TV show about race.Second, the timing of the show is equally wrong. “Black and white” operates in a time capsule that has nothing to do with the contemporary realities of globalization. I find it fascinating that a show such as “Black and White” can still received a greenlight at the time where race relations in America is becoming increasingly complex with signposts such as 9/11 and the debate on immigration which is heating up all over the country. My experience, moreover, teaches me that racism is not simply a black and white issue. It cuts across races and classes. There are racists in every single race on earth not simply between blacks and whites. Thus, reducing racism to simply Black and white issues, might yield some insights, but in the overall issues of race relations is outdated and much uncomplicated.Third, it is the whole idea of reality TV itself that has always bugged me. Everything on that show seems staged, manipulated and insincere. This is not reality-TV but somebody’s fantasy about what race is in America which is very antiquated.Overall, I think that the show is clueless about race. It shows that a country entrenched in the ideology of liberal individualism and psychology cannot successfully address issues of race.

From what I observed from watching the show. It seemed to me that reverse predijice was more at work here. The black family seemed to have a chip on their shoulders. I had to agree with Bruno about people being treated according to their attitude they give off. If you always think that everything negative that happens to you is becuase of your race, guess what? you’ll alway’s be finding things you can turn into racism. I know there is racism out there, but what people need to understand is it’s becoming less and less all the time. And if they would not pass their negative beliefs on to their children, eventually it would just about dissapear. But we have to let go and not alway’s think every thing white people do is done in malice. Every time they dont get waited on rite away at a store, ect. Guess what? im white, and sometimes I dont feel like I get treated fair at all. Let’s all grow up and quite playing the worn out race card.

Black? White?

Unfortunately I never got a chance to see the show but from what you described above it seems like the shows portrays race wholly on the color of ones skin. The show seems to put people in a situation they are unfamiliar with creating tension and anxiety. The show mainly seems to focus on the “other”, that which is non-white.

“Black. White.,” is exploiting the issues around race and what it means to be black and white in our society. Society tends put labels on people based on their skin color but actually being part of the race is much different that faking it.

Racism does exist in our society and this show only complicates the issue. I can see how the show encourages dialogue about racism, which many people tend to not want to talk about these days but it does so in the wrong way.

The formation of race occurs through historical events, social practices, and is linked to the evolution of hegemony. From what you described above the show is doing what took hundreds of years to create. The formation of race also has to do with the destruction and well and the show is most likely destroying racial boundaries.

I think the show’s goal was to give people a chance to observe what life is like as being black and white from a different perspective however all the show did was portray what life is like as the “other”.

The ideas of empathy and compassion are all important when look at racism in society and therefore the show did have some impact on how people think about racism today.

Racism or No Racism?

I have never seen the show “Black and White”, nor had I heard of it until reading Kim’s article, but it sounds like a very interesting idea that potentially could reveal a dozen different conclusions. Kim’s emphasis on the different way the older and younger family members deal with their change in race is particularly eye opening. Rose and Nick, who represent the “post-race era”, accept each other and notice no form of racism when they are black or white. To them the world is beyond segregation and has fixed its racist habits. On the other hand, Nick’s parents, Brian and Renee, see a difference in the way they are treated when they are white and when they are black. This is probably because they grew up during a time when obvious racism was everywhere and black people had to fight for their equality. As a result they continue to see the world as a racist place. The question is, who is correct? Is racism gone from the world, as Rose and Nick would argue, or is it still here, as Brian and Renee would say? To a certain extent I believe that both are correct. The problem of racism in America has come a long way and is much better now then it was even forty years ago. But to say that it has completely gone away is untrue. Many people believe that it has because racism has gotten very good at camouflaging itself in popular media. For example, we no longer see a crazed black man trying to rape a doll-like white woman, as seen in the 1915 film Birth of a Nation, but we will see a surprisingly large number of cracked out black men and women being arrested on “Cops” (1989- present). This image, which most of us pass off as a coincidence, non-the-less creates a psychological schema in our mind that says most black people are criminals (Gray, 1995). The idea of a black person being a criminal is by no means a new stereotype, which is why we accept it and hardly notice it portrayed week after week on “Cops.” Therefore, it makes sense that Nick and Rose, who never experienced such obvious racism as their parents did, believe that racism does not exist; the media is just too good at covering it up. Nick’s parents on the other hand, know what it means to be suppressed, and notice the subtle acts of racism around them. This is why the “post-race generation” does not notice racism while their civil rights parents do.

• Gray, Herman. (1995) Television and the Struggle for Blackness. “Watching Race”