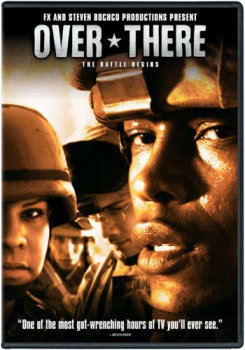

Bring the War Home: Iraq War Stories from Steven Bochco and Cindy Sheehan

FX’s Over There

American television has been telling two separate but interestingly related stories about the war in Iraq this past month. One is Over There, producer Steven Bochco’s highly touted new series for the FX cable channel which purports to be the first dramatic television series depicting a war while the country is still engaged in combat. The other is the non fictional story the cable and broadcast news shows have been telling about Cindy Sheehan, the mother of a slain American soldier who has been protesting outside President Bush’s ranch in Crawford, Texas during his rather long summer vacation. Both these stories are instructive for what they suggest about how this war is being made sense of right now. They also provide instructive comparisons to the way U.S. television handled the last war-as-quagmire into which Americans found themselves sinking.

Publicity and commentary about Over There have made much of the fact that the series depicts fictional US soldiers while their real-life counterparts are still fighting and dying. Let’s remember that M*A*S*H also debuted while the war in Vietnam raged. Of course M*A*S*H wasn’t actually about Vietnam, even though, of course, it was. However, as I’ve written about elsewhere, prime time TV, especially during the so-called “season of social relevance” of 1970/71, but to a lesser extent before that as well, did acknowledge and represent versions of the conflict, albeit largely about the “war at home” (Bodroghkozy, 2001). It took the entertainment divisions of the networks a significant number of years before they decided that they needed to take notice. Nevertheless, Over There is not as remarkable a moment in TV programming history as many observers seem to think. What is novel about the series is its attempt to portray ripped-from-the-headlines combat, and to do it without the cover of comedy or without displacing the events into an easier-to-manage past.

As sentiment about the Iraq war have been getting increasingly polarized of late, it is interesting to look at the debates that have gathered steam about whether the show is fundamentally pro or anti war in its portrayal of the conflict.

Commentary is all over the map: The show is antiwar. The show is pro war. The show is inaccurate. These conflicted and clashing readings may be exacerbated by Bochco’s insistence over and over again that the series does not take a political position about the war. Larry Gelbart, M*A*S*H’s producer, was similarly reluctant to admit that his show had a political stance about the specific situation in Vietnam (Gitlin, 1983, p. 217). In both cases, we have classic cases of the “polysemic” text, although the preferred anti-war encoding of M*A*S*H seems hard to miss, even though some viewers apparently negotiated readings that were positive about military service (Gitlin, p.217). Bochco’s series is in some ways not unlike Gelbart’s show in its representation of war and its personnel (whether soldiers or doctors). Both shows focus on daily life and “muddling through.” The grunts of Sargeant Scream’s unit do so grimly, doggedly, and humourlessly. The doctors and nurses of the 4077th did so with jokes, wild antics, sex, and an appreciation for the absurd. In both cases, the reasons for the war are largely unexplored. By focusing so closely on the “grunts’ eye view,” Over There gives us a war that is mostly about staying alive and seeing enemies everywhere since there is no defined battlefield. All Iraqis could be terrorists, much like all Vietnamese could be VC. The show’s representational strategies owe a great deal to the visual codification of the Vietnam war, especially in cinema. More generally, it’s a war with no articulated purpose, rationale, or definition of victory. A conversation between two characters (one Arab American) let’s us know that both enlisted because of 9/11; episode three gives us a jihadist terrorist to hate. But are these troops in Iraq to fight a war on terrorism? The show doesn’t tell us. In the interests on avoiding “politics” Bochco and his team have managed to give us a Vietnam-esque war, both visually and thematically. It isn’t absurdist the way that M*A*S*H’s “Vietnam” was (war on godless communism — yeah, right!), but it certainly isn’t heroic.

The series’ inability or unwillingness to posit a clear purpose for the war connects it neatly to the other major Iraq story that television and other media outlets have been following intently this summer. The Cindy Sheehan story is a narrative of the home front and one that is probably easier for television to tell than the one Steve Bochco wants to tell. (Ratings for Over There, which started very strong for a cable offering, have sagged since the premier.) The costs of the war are effectively personalized in the figure of the grieving, but strong mother. Soap opera-ish drama gets injected into the story by the continuing question of whether an emotionally callous president will meet with this lone embodiment of suffering motherhood. The story also produces great visuals of emotional impact such as the tiny crosses representing dead soldiers that Sheehan’s supporters at the Camp Casey encampment erected. The dramatic visuals were only enhanced when the crosses were mowed down by opponents of the protest. The melodramatic qualities of this story are then further enhanced with the failed attempt to “swift-boat” Sheehan. Our heroine must suffer, and suffer, and suffer some more. That Sheehan needed to attend briefly to her own mother’s medical crisis and that her husband filed divorce proceedings against her only solidifies her status as a quintessential melodrama heroine.

This is the kind of war story that television knows how to tell. This is the kind of war story that audiences may find more compelling. Like Over There, the Cindy Sheehan story begins with the premise that there is no clear rationale for the war. The problem with Bochco’s series is that it takes this as given and then proceeds with the assumption that the narrative doesn’t need to grapple further with this matter. Sheehan’s story is a “successful” one because it doesn’t accept the “muddle through” theme. Sheehan’ story is a quest to find meaning and truth: why did her son die? That her quest galvanizes large numbers of supporters who either join her vigil or who support her with candle lit vigils from afar only increases the poignancy of the story. Over There just cannot compete with the legible “moral occult” Sheehan’s Iraq story constructs.

The Bochco series and the Sheehan story share another similarity: both focus entirely on the Iraq war as a story about military personnel: soldiers and their families. American civilians and those not in some way connected to military life are irrelevant to the story. Over There‘s major home front story involves a member of the squad whose leg was blown off by a roadside bomb. In episodes to date, we see him struggling with the VA hospital and his diminished sense of masculinity, while his loving and supportive wife provides nurturance. Other home front stories also concern themselves exclusively with the loved ones (faithful and not) of the troops overseas. Sheehan’s story is remarkable for the emphasis on “Gold Star Families” as the representatives and activists of this new antiwar movement. Those who have joined Cindy at Camp Casey and make the news are mostly other military moms. Those who are trotted out to provide a counterbalance to Cindy’s arguments are also mothers of soldiers.

These narratives suggest that both the fighting of this war and the protesting against it are jobs for non-civilians and their loved ones. The role of civilians (either those who may support the war or those who oppose it) is a vicarious one: you can watch.

The war in Iraq has been an odd kind of non-event for most Americans. Unlike World War II, the Iraq war has not resulted in total war mobilization by the entire population. Unlike Vietnam, all able-bodied young men (and their families, girlfriends, and wives) don’t need to confront the prospects that they may be drafted to fight this war. The war is already rather fictitious to most Americans. Aside from news coverage (which one can avoid and which gets easily knocked off the headlines by natural disasters like the tsunami or Hurricane Katrina or by human disasters like Michael Jackson), little in Americans’ daily lives forces them to confront, engage with, or acknowledge that there’s a war going on. I suspect that there may be a certain amount of unease about that. Shouldn’t we be sacrificing something for the war? Aren’t we supposed to be doing something? If we support it, shouldn’t we be participating? If we oppose it, shouldn’t we be protesting in the streets?

To some extent Over There and Cindy Sheehan’s narratives provide a simulated way by which Americans can use their TVs to pretend to be involved with this war. Consider the audiences for the Bochco series. Why would anyone want to watch a relentless, graphically violent fictionalization of a war that, especially recently, has generated significant up ticks in the number of U.S. casualties? I’m wondering to what extent watching this show allows some viewers to experience emotionally and viscerally a war that otherwise is largely a nonevent in most Americans’ experience. Bochco’s series gives audiences something to do: they can go to Iraq vicariously with the troops. They can identify and empathize with these fictional stand-ins for the real troops and feel patriotic doing so. In a hyperreal war fought on television (although not cleanly and according to a predetermined script, a Baudrillard’s Gulf War), and fought by a professionalized military not needed a civilian population to assist, what else can the folks back home do to feel involved?

And what about those who oppose this war? Considering how quickly the war has become unpopular and considering how widespread the dismay and disillusionment has spread about both the reasons for the war and its winnability, the lack of an activated grassroots protest movement seems odd. However, if the war, for the majority of Americans, is a hyperreal conflict fought on television, then perhaps it makes sense that when antiwar activity finally does erupt, it does so as a made-for-TV soap opera. And because the majority of Americans really aren’t involved, our antiwar activists could only be those connected to the institutions of militarism. Those of us who hate the war, but really aren’t affected by it, align ourselves with Cindy and turn her into our heroine. She and the other grieving Gold Star mothers become our televisual surrogates. They organize a hyperreal antiwar movement made up largely of military families, the only Americans actually impacted by the growing carnage in Iraq.

Will this hyperreal antiwar movement centered around one melodramatic heroine develop into an actual movement with grassroots mobilization among citizens not directly connected to the military? Or will it remain a media event like the professionalized war it protests? I suspect we will mostly remain spectators, voyeurs, tricking ourselves into believing that we are actually engaged with and involved in this awful drama of human slaughter.

Bibliography

Baudrillard, Jean. The Gulf War Did Not Take Place. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1991.

Bodroghkozy, Aniko. Groove Tube: Sixties Television and the Youth Rebellion. Durham, NC. Duke UP, 2001.

Gitlin, Todd. Inside Prime Time. New York: Pantheon, 1983.

Image Credits:

1. FX’s Over There

Links

Over There homepage

Cindy Sheehan website

Please feel free to comment.