The Value of Lost, Part Two

by: Jason Mittell / Middlebury College

In my previous column on Flow, I argued for the importance of evaluative claims within television scholarship, a position I expected to be contentious among many readers and contributors to this site. Alas, controversy was lodged elsewhere that week, as Aniko Bodroghkozy’s column revisiting the political economy vs. cultural studies debate captured the collective argumentative mindset of Flow (even in meta-debates, politics trumps aesthetics within media studies yet again!).

Still, evaluative criticism seems to be not quite acceptable within most media studies paradigms, as value is assumed to be completely relative and subjective by the majority of academic critics. Thus to offer another way of valuing television, I return to my initial

claim: that Lost is the best show on American broadcast TV. In defending such a claim, I’ll try to suggest how evaluative criticism might proceed: by highlighting the criteria of value the show fulfills, and justifying such criticism within broader contexts of medium and culture.

Ultimately Lost offers an aesthetics of surprise at every turn. For a medium that is nearly defined by its predictability — of schedule, of genre, of narrative form, of character type, and of commercial rationalization —Lost dares to surprise us at nearly every turn. When the pilot debuted in Fall 2004, my own anticipation stemmed from the track record of co-creator J.J. Abrams, who had already given me three years of pure TV pleasure through Alias. He had earned my trust enough to give anything he put his name on a chance.

What I discovered as I began to watch was consistently surprising. The first surprise was the premiere’s depiction of the plane crash — few sequences I’ve seen in my years of television connoisseurship offered such unflinching intensity. My expectations were at once raised and diminished — how could this work as a series? Like many, I approached Lost with frames of reference of other deserted-on-an-island narratives, from Lord of the Flies to Survivor (or if it turned out to be a true disaster, Gilligan’s Island), assuming that the story would focus on the castaways’ struggles to escape from and survive in an isolated world. And if this were the sole thrust of the narrative, it would be disappointing, as nothing could match the intensity of the show’s opening moments.

But as with nearly every element of Lost, first impressions are misleading. The island is not what it seemed at first, just as each character and event turn out to be more than they first appeared. Thus the show’s genre is not what it first appeared to be — this is not television’s attempt at a disaster show (a genre seemingly unsuited for an ongoing situation and storyline). Ultimately the show’s genre still remains uncertain even after an entire season — is it a supernatural thriller, a scientific mystery, a soap opera in the wilderness, or a religious fantasy (or all of the above)? Unlike previously lauded genre mixtures like Twin Peaks or Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Lost refuses to wear its genre references on its sleeve, preferring to allow audiences to speculate on relevant interpretive and aesthetic frameworks, and then confound our expectations through twists and reversals.

Another level of unexpected pleasure comes from the show’s unique storytelling structure. On the face of it, the compelling narrative questions and pleasures would appear to be predicated on the suspense of what will happen to the survivors — will they get off the island or will the “Others” (the island’s mysterious inhabitants) get them first? But the show has created equally compelling narrative enigmas in the back story of each character — what were Kate’s criminal acts and motivations? How did Locke get paralyzed (and acquire his uncanny outdoorsman expertise)? What happened to the previous crash victims decades before? And why were these people brought together on this airplane and then spared in the crash? In probing these mysteries of both the past and future, Lost balances notions of fate and randomness, overdetermined causality with blind chance, a thematic richness that also keeps a rapt audience guessing.

This storytelling scope is carried out in a truly innovative discursive style, with nested flashbacks structured into the routine episodic form. Every episode foregrounds one character’s backstory, interweaving past events with the challenges of life on the island to create parallel narrative threads which resonate in often surprising ways. At its best, Lost offers intricately crafted puzzles which partially reveal themselves each week while adding new complexities and mysteries to the richly drawn characters and the snapshots of their pre-crash lives.

Lost’s level of narrative innovation and complexity follows other programs which tried to create dense webs of paranormal mystery, but eventually collapsed under the weight of their own ambitions and infinitely delayed resolutions, most notably Twin Peaks and The X-Files. Interviews with co-creator Damon Lindelof acknowledge this debt, but also reassure fans that Lost learned the lessons of its ancestry, promising that not only will the show regularly deliver on (at least some) answers to central enigmas while maintaining ongoing suspense, but also that the creators have a master plan for the over-arching narrative — reportedly having mapped out a six year plan, if the Nielsens hold out!

Confidence in the producers’ control of the complex narrative is evidenced in the show itself, as nearly every episode pulls off at least one moment of storytelling bravado that leaves me gasping on the couch. For a show with such a high-budget and elaborate visual style, the most impressive special effects are accomplished within the writing itself — sophisticated and surprising twists, reveals, and structures offer what we might consider storytelling spectacles, a contemporary “television of attractions” that asks viewers to marvel at the sheer bravado of the creators. From the reveal of “the numbers” on the hatch to the finale’s capture of Walt, these moments awe us with the audacious demonstrations of how original and surprising a television show can be.

An exemplary episode is “Walkabout,” a fan favorite which certainly was the hour that catapulted the program into my personal canon. The episode focuses on John Locke, the island’s resident shaman/safari guide, whose expertise knows no bounds — a role that’s confounded when flashbacks reveal that before the crash, Locke was a cardboard box salesman with a penchant for phone sex. On the island we learn that Locke traveled with a suitcase full of hunting knives and can hunt wild boar; the flashbacks reveal that Locke was bound to a wheelchair and denied a chance to go on an Australian walkabout, the reason he’s on the doomed flight in the South Pacific. The island’s first manifestation of seeming paranormality, the reveal of Locke’s earlier disability and subsequent healing, is breathtaking, visually intricate and heightened by the power of the Terry O’Quinn’s hypnotic performance.

Lost’s dense narrative complexity is coupled with a robust sense of character depth — without the engaging richness of the castaway’s personalities, the twists and suspense would grow tiresome or predictable (see 24), or lack emotional connection beyond the narrative gimmicks (see Desperate Housewives). Each character has a seemingly infinite past, comprising rich backstories that add resonance to island scenarios. In sculpting the castaways’ pasts, the show draws upon a range of generic traditions, including melodrama (Sun & Jin), comedy (Hurley), crime stories (Kate and Sawyer), medical drama (Jack), military drama (Sahid), and family saga (Walt & Michael, Shannon & Boone). This adds to the show’s effect of surprise, as viewers have a wider horizon of expectations to draw upon than any other program, and thus moments that may be somewhat conventional within one genre, such as Sun and Jin’s tearful reconciliation in “Exodus,” resonate as more honest and effective due to their unpredictability and freshness in contrast to the show’s wide ranging tonal palette.

Plus Lost looks and sounds better than anything else on the air, with an eerily effective musical score, bold and beautiful cinematography, and stunning use of the on-location setting of Hawaii. Watching Lost both plays to the strengths of the television medium — serial structure, ongoing narrative and character depth, ritual engagement — and overcomes many of its typical weaknesses — flat visual style, generic predictability, repetitive formulas. We could look at these textual elements with pseudo-objectivity, effacing value judgments for by using coded terms like “richer” and “more nuanced,” but in considering television’s aesthetic practices, we should be honest with what we mean: the show is better than its peers.

By understanding what makes Lost so much better than most television (a success that’s thankfully been borne out by the show’s ratings), we can get a stronger sense of how the medium’s norms typically operate and may be transcended, the range of televisual practices that engage audiences, and the potential for innovation within a traditionally risk-averse industry. Lost’s value is in pointing out both what television at its best can be, and what we television scholars can learn by acknowledging and engaging with the concept of “best.”

Links

Official Lost Site

Unofficial Fansite for Lost

Image Credits:

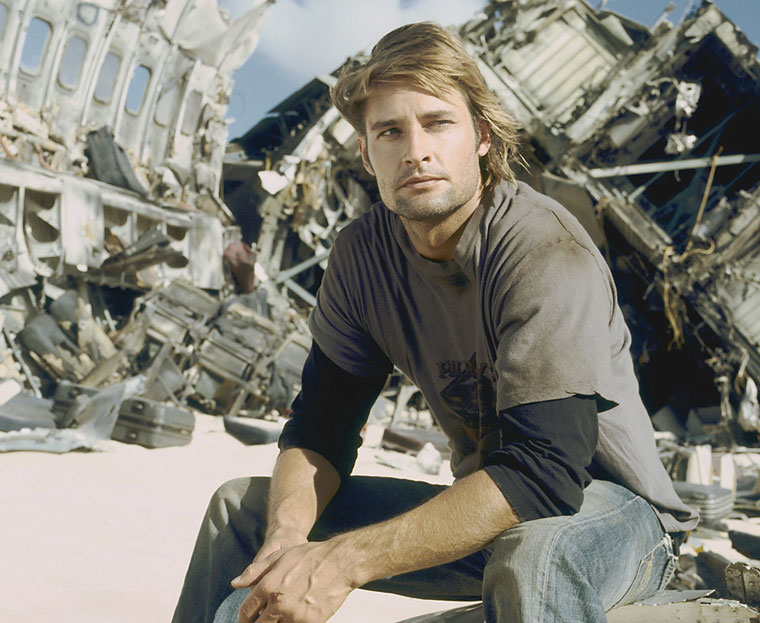

1. Plane crash

2. The cast of Lost

Please feel free to comment.

valuing television

I have greatly enjoyed these commentaries on Lost. As with you, I make no apologies about using my position as teacher, to introduce interesting–and often challenging– programmes to my students. Some in my Year Two “Television: Medium, Narrative & Audience” course have already found a number of these–Lost, Curb Your Enthusiasm, Jon Safran vs God (Aust), Little Britain (UK), Brass Eye (UK), Desperate Housewives + Six Feet Under etc . Regarding your earlier comments about the dearth of dialogue regarding ‘quality’ in television studies, there is some work going on. I have just sent off a chapter (on the notion of quality on New Zealand television) for an upcoming book–“Defining Quality Television”, co-edited by Kim Akass (London Metropolitan Univ) and Janet McCabe (Manchester Metropolitan Univ). It has an American publish + numerousAmerican contributors and will be out next year.

best wishes from Down Under.

I just thought I’d let you know know that I think You are right LOST is the best! I love the suspense and them not answering questins so that I can imagian what will happen next. THANKS

Audience, complexity and superiority

I, too, have greatly enjoyed these articles, even though I haven’t seen a single episode of Lost. That’s a testament to how cogent and, dare I say it, objective the critique is. If someone tells me they love a show because “it’s good,” that’s the end of the conversation. Here, I think we’ve got a common language.

I’d like to come up with a clearer idea of what the aesthetic frameworks audiences bring to a show like Lost might be. I think that’s as important, as much a part of the equation of determining what makes for pleasurable, rewarding television, as textual analysis. Perhaps there’s a group of people (puzzle solvers) who are predisposed to shows with such ambiguity and complexity. To me, “complex” isn’t necessarily good, nor is it universal. Different audiences have different levels of generic literacy, and the highest levels of pleasure come when an audience is challenged but not confounded. This is mere speculation on my part, but I’d just like to think about complexity, enjoyment and aesthetic superiority as they relate to different clusters of people with definable, predictable tastes (or, if you like, varying levels of literacy).

Pingback: FlowTV » Teen Choice Awards: Better Than The Emmys?

Pingback: FlowTV » What is Lost?

Pingback: FlowTV » The Los Angeles Misanthrope

Pingback: FlowTV » Exchanges of Value

Pingback: FlowTV » We Are So Screwed: Invasion TV

Lost has Value

Lost definately is one on the best shows on television these days. The fact that it has such a great storytelling structure is captivating. I also like the fact that it isn’t limited to just one genre, it actually have a number of genres that allows the viewer to get a taste of the genre of thier choice. This article is great in explianing “why” Lost is the best show on television.

Pingback: Course Information « Pop Culture E2043