This Week on Flow (April 15, 2005)

by: Allison Perlman / FLOW Staff

This Week on Flow

The cover story in this past Sunday’s New York Times Magazine, Our Ratings, Ourselves by Jon Gertner, details some of the new Orwellian technologies developed by gurus in the ratings business, at the behest of advertisers, to fine-tune information about what we’re watching, how much we’re watching, and where we’re watching. The portable people meter (P.P.M.), for example, is worn by individuals during their waking hours and monitors all the television and radio programming they have been exposed to all day. Arbitron has developed an encoding device that all broadcast programming can be run through that can provide much more accurate information than the current use of Nielsen families. This article thus reiterates an insight of Dallas Smythe’s of so many years ago: that the main commodity in broadcasting is us, the audience itself. Seeing television as an engine of commerce, Gertner’s piece reminds us of the somewhat bleak characterization of the viewing audience: as consumers of products and as that which is consumed by sponsors.

As this week’s contributors to Flow so ably demonstrate, the above construct is but one way to answer the questions: “what is television?” and “what is our relationship to it?” Indeed, the columns in this issue illustrate the myriad ways we can define “television” and the many roles it plays in our lives, far outside of the realm of commerce. John Hartley, for example, challenges media scholars to see television not through lenses of disgust and disappointment, but as a potential productive, educational and civic site of interaction — as something to love rather than to deride. By charting the impact of an episode of “Jamie’s School Dinners,” Hartley demonstrates that television can inspire audiences to participate in the world outside of their living rooms. Functioning like a public square, television in this instance can be a spur for civic engagement and action.

In a similar vein, Jim McGuigan’s column on the British Broadcasting Corporation argues for the retention of public service broadcasting. He focuses on the recent book on the BBC by Georgina Born and her conclusions on strategies to revitalize public service broadcasting and its ancillary online services. This issue is of grave concern, according to McGuigan, because it is a necessary stopgap against the “overwhelming privatization and commodification of information, knowledge and culture.” Denying the neo-liberal logic that puts so much faith in the market, McGuigan’s work suggests that at least a sliver of broadcasting should be outside the realm of commerce so that it can provide a much needed site of public discourse. His vision, in fact, echoes that of Hartley in his piece of Flow: that of television as facilitator of public debate and action. Whereas Hartley sees this potential in contemporary commercial television, McGuigan argues for the need to divorce broadcasting from commerce in order to ensure its civic vitality.

Frederick Wasser, in line with McGuigan’s concerns over the impact of neo-liberalism on media policy, addresses a potential — and unexamined — consequence of the increased media concentration that has resulted from spiraling media deregulation: increased vulgarity and drivel on-screen. Attributing this hypothesis to FCC commissioner Michael Copps, Wasser investigates whether the growth of enormous media empires facilitates the concurrent growth of smutty and intellectually-barren programming. Envisioning television as the nexus of regulatory decisions and business practices, Wasser additionally imagines audiences as interested parties — not only in what is on-screen but in the very decisions that happen in the world of the FCC and global telecommunications.

Patricia Aufderheide, this week’s guest columnist, also addresses the issue of ownership, but from a different perspective from Wasser. While Wasser examines the impact of consolidated ownership of media companies, Aufderheide examines the ownership of intellectual property, images, songs, and video footage and the impact of copyright regulations on documentary filmmakers. She illustrates that, with growth of media consolidation–and the concurrent consolidated control over archives–filmmakers are increasingly limited in the type of films they can make. For Aufderheide in this article, televisual images (along with other forms of expressive and visual culture) have a dual and conflicted function: at once integral parts of the public’s collective cultural repository and as private legal possessions of companies.

The tact taken by Chris Anderson in addressing the question “what is television” reminds us that the impact of the television industry has a wide ripple effect that extends beyond what we see on our screens, and that the conglomerates that run the media produce not only its content, but the very technologies we use to interact with it. Specifically, Anderson focuses on the horrendous environmental and health consequences that resulted from Westinghouse’s (which merged with CBS in the 1990s) decades-long practice of depositing electrical capacitors in a landfill in Indiana. Anderson uses the case to illustrate a larger point about the growth of entertainment technologies: that their introduction not only widens or transforms our entertainment experience, but causes unseen and hidden consequences by their very manufacture.

Brian Ott and Sharon Ross, rather than focusing on the structures that control the media, examine the different pleasures that viewers can derive from it. Ott sees the appeal in Jeff Foxworthy’s Blue Collar TV a latter-day version of Rabelaisian “carnival,” or the inversion of norms of politeness and accepted social codes. While noting the irony that this challenges comes by way of a multi-millionaire on a network owned by one of the largest media conglomerates in the world (AOL Time Warner), Ott’s emphasis on the text and its appeal to a working class audience acknowledges the complex relationship between media consumers and media producers, one that allows for viewers to consume the product of the dominant culture industries while engaging in interpretive activities that subvert that values that it rests upon.

Ross writes of the pleasure for viewers of the process of unraveling mysteries on television shows like Desperate Housewives, Lost, Medium, and others. Ross maintains that allure of such shows in is getting to participate in ongoing mystery-solving, of the process of asking questions about what is happening, and not in the satisfaction of ultimately finding out. As viewers, we are actively involved in the mysteries at hand, constantly trying ourselves to solve the puzzles with which the shows tease us. Like Ott, Ross’s television viewer is actively involved in meaning-making and, indeed, it is this engagement that provides the pleasure.

Finally, Rachel Weiss’s piece investigates blogs from the vantage point of an active blogger. Weiss details the rise of the blog and its adoption by many mainstream media organizations. But at the heart of her column is a view of the impact of this new technology that is seemingly accomplishing what years of regulatory efforts, American broadcasting, and cable had failed to do: allow the media to be truly interactive and to provide a space for multiple voices to be heard. Implicitly, her article underlines some of the failures of television to create a mediated public sphere and, in turn, celebrates how the advent of new technologies has filled the gap.

To a large degree, the columns in this journal have consistently been in conversation over “what is television” and “what is our relationship to it.” This week, in particular, with the somber chords hit by the New York Times piece still so fresh in my mind, this week’s columns provide a provocative and engaging discussion of these very issues. I am inspired, at least for the moment, to turn on my television again, regardless of whether my affection for Meet the Press and the Iron Chef is being charted by faceless market researchers lurking out there, undetected.

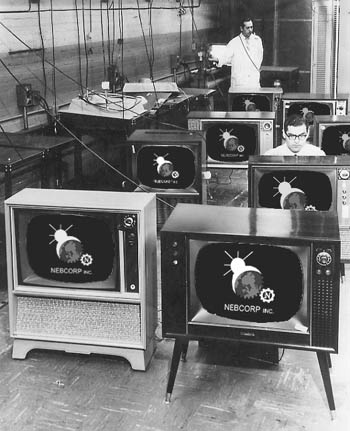

Image Credits:

1. This Week on Flow

Please feel free to comment.