Boys Love (BL) Evolving into Gay Love?: Exploring the Popularity and Transformations of BL in Contemporary Korean Media

Jungmin Kwon / Portland State University

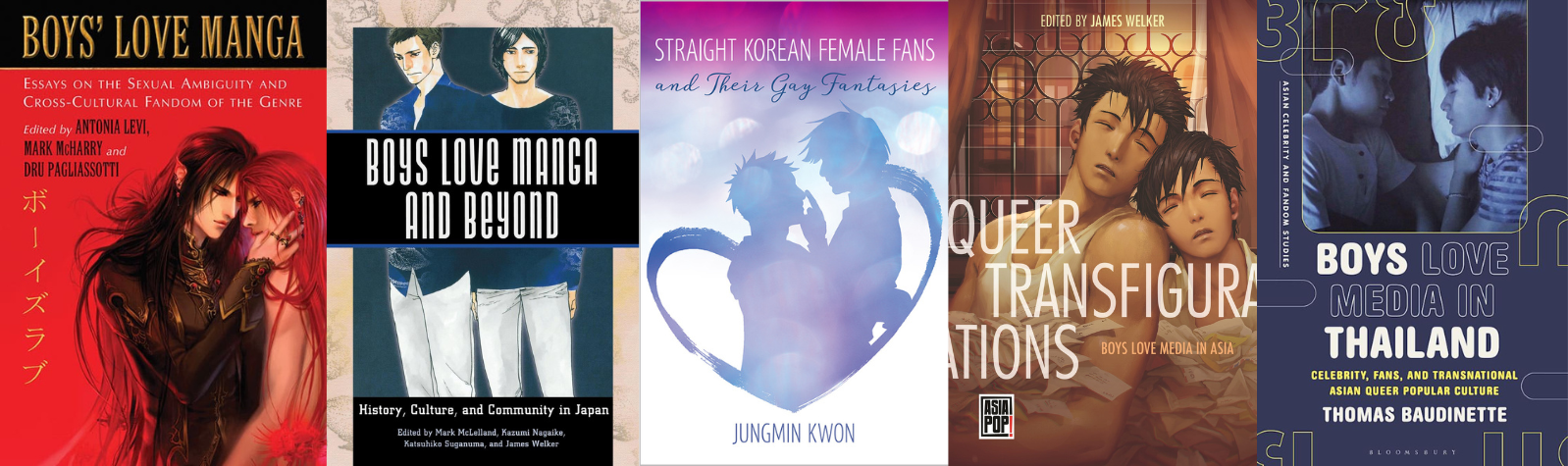

Boys Love (BL) may sound unfamiliar to people in the West, where another similar genre, referred to as slash fiction, has more cultural and academic currency. Essentially, BL is a media genre originating in Japan that features male homoerotic relationships. It started in the late 1970s with (mostly female) fan-written works, broadly labeled as yaoi, an abbreviation of yama nashi, ochi nashi, imi nashi (‘no climax, no point, no meaning’). Later, as the fan subculture was appropriated by Japanese commercial publishers, the term BL, once used to indicate commercialized gay romance narratives targeting mainly female audiences, became prevalent compared to yaoi and now functions as an umbrella term for the genre. Yaoi/BL also found its way into markets in other neighboring countries, including Taiwan, South Korea (hereafter Korea), and China, where similar subgenres, such as K-pop idol fanfic and danmei (‘indulging beauty’) are popular. Today, in Southeast Asian countries such as Thailand, the Philippines, and Indonesia, BL also enjoys a large following. Thanks to the wide distribution of digital technology, Yaoi/BL is even circulating widely in some Western countries,[1] and its fans and slash fans interact and consume each other’s texts; for example, Archive of Our Own abounds with BL-related posts. Even within Western academia, BL is increasingly taken seriously with several scholarly books in English (see figure 1) and a journal special issue published on the topic, supplemented by various symposiums, workshops, and conference panels.

As a scholar who has authored a book and several papers on BL subcultures in Korea and East Asia, I have observed a significant transformation within the BL sphere in Korea in recent years. When yaoi was first introduced to Korea in the 1980s, its circulation was restricted due to social and cultural conservatism, leading it to exist primarily within underground fan communities. The advent of dial-up internet service in the mid-90s facilitated the migration of yaoi writers and readers to online platforms. Subsequently, in the 2000s, the production and consumption base of yaoi expanded via Internet cafes, writers’ personal web pages, and BL-centric websites. Since the mid-2010s, the landscape has shifted with the rise of online commercial publishing platforms like Lezhin, Ridi, Joara, Kakaopage, Naver Series, Comico, and Bomtoon. Many BL writers have flocked to these platforms, significantly broadening readership and contributing substantially to the profits of these platforms.[2 ] As such, BL has experienced unprecedented levels of popularity and commercialization.

Various factors have contributed to the popularity of BL in Korea. Koreans, who are heavy users of mobile devices while on the move, have come to prefer content that can be consumed in a short period of time, giving rise to a new mode of media consumption called “snack culture.” Accordingly, the prominence of web content, not only webtoons and web novels but also web drama series, has drastically escalated. To respond to the demand for diverse and new content, BL narratives have emerged as a new and trendy genre. Of course, this rise can be attributed to the fact that younger people, millennials, and Gen Zers (so-called MZ sedae in Korea), who are the main consumers of snack culture, possess a more open perspective toward queer issues than the preceding generations. Consequently, BL has emerged as a cash cow for publishing platforms. As One Source Multi Use (or transmedia storytelling) is on the rise in the Korean media industry, BL web novel and webtoon-based narratives are increasingly employed within web drama series, films, books, ebooks, and commercials. For example, the 2018 web novel Semantic Error was adapted into an audio drama of the same name in 2019, a webtoon in 2020, an animation in 2021, and a TV series and movie in 2022 (See figure 2). Some of these were translated into multiple languages and well-received in other countries.

The popularization and commercialization of BL material has contributed to shifting its authors and audiences beyond the traditional fan base of heterosexual women, who were believed to be at the core of BL subcultures traditionally. Here, I would point to the diversification of BL content makers as a particularly significant development. BL has long been criticized for engaging in misogyny and the objectification of gay people. Despite women being the main producers and contributors, female characters rarely appear in BL, or are plot devices included only to drive male-male romance narratives. However, since the Feminism Reboot movement began in Korea in the mid-2010s, the number of fans leaving the BL subculture has increased and criticism toward misogynistic tendencies has intensified, expediting critical discussion and self-reflection within BL communities.[3 ] Also, the longstanding queer critique of the creation of glamorized male same-sex romance narratives for consumption by straight women is at an interesting juncture as gay media producers are joining the BL industry. For many years, the Korean gay community had constituted a proportion of BL consumers. As BL became more known, gay audiences have become more engaged and some gay media content makers now often venture directly into production.

For instance, established gay film producer/director Kim-Jho Gwangsoo and gay director So Joon-moon, who previously created films related to gay life and rights, recently released BL drama series named The New Employee (2022) and Love Mate (2023), respectively.

When I interviewed So Joon-moon and Kim-Jho’s partner, Dave Kim from Rainbow Factory (a film studio and distributor for queer cinema), for my book project in 2021, they disclosed their BL productions. They explained that through BL as a platform, they were aiming to foster new possibilities for gay representation. Notably, they both independently stated that the idealized world depicted in BL, where gay people were not discriminated against and could display their sexuality without hesitation, might help to showcase the possibility of BL as a “progressive genre” representing the future that gay individuals are striving to realize.

Those accusing BL of depoliticization and ignorance about gay reality may want to consider the generational shift regarding what kind of realities younger gay media consumers in Korea aspire to see in media. In conducting interviews with younger gay audiences in 2021, I noticed their increasing desire for media content conveying more mundane and lighthearted narrative themes than dark realities and political matters. In my 2019 book, my gay interviewees addressed that they could relate to some of the stories in Antique (2008) directed by a cishet male director, a movie adaptation of a Japanese BL comic, but found No Regret (2005), directed by a gay film director, unrealistic and uncomfortable.[4 ] Many gay people in their twenties and thirties that I interviewed exhibited considerable openness towards BL, and all of them declared that they did not have any issue with non-queer people producing queer-related content. In this sense, BL content can sometimes appeal to the sentiments and desires of the younger gay population in comparison to media that delves into bleak and unfortunate narratives about gay life.

Here I by no means mean to claim that BL is a beneficial fiction genre orientated toward gay people. It is not even BL’s primary purpose. Instead, I simply share the observation that BL production and consumption are evolving to embrace diverse voices and identity positions while acknowledging critical perspectives and responding to them. BL had already established itself as a distinct media genre, albeit largely hidden from mainstream audiences. In the era of digital transmedia storytelling, it serves as an expanding genre for exploring new possibilities and seeking new solidarities. BL, while occasionally lacking ethical sensitivity or relevance to feminist advocacy, has the potential to serve as a platform for progressive representation of marginalized minority groups in mainstream culture, fostering solidarity among these communities as it is becoming an integral part of the contemporary media landscape in Korea. In this context, anyone, not least feminist or gay BL content makers and audiences, should and could leverage this trend to promote progressive and relatable ideas if they desire.

Image Credits:

- Scholarly books on Boys Love (Boys’ Love Manga: Essays on the Sexual Ambiguity and Cross-Cultural Fandom of the Genre, ed. Antonia Levi, Mark McHarry and Dru Pagliassotti; Boys Love Manga and Beyond: History, Culture, and Community in Japan, ed. Mark McLelland, Kazumi Nagaike, Katsuhiko Suganuma, and James Welker; Straight Korean Female Fans and Their Gay Fantasies, by Jungmin Kwon; Queer Transfigurations: Boys Love Media in Asia, ed. James Welker; Boys Love Media in Thailand: Celebrity, Fans, and Transnational Asian Queer Popular Culture, by Thomas Baudinette)

- Covers and posters for versions of Semantic Error (web novel, audio drama, webtoon, animation, TV series, film)

- BL drama series The New Employee (2022) and Love Mate (2023)

- Posters for Antique (2008) and No Regret (2005)

- Paul M. Malone, “Transplanted Boys’ Love Conventions and Anti-‘shota’ Polemics in a German Manga: Fahr Sindram’s ‘Losing Neverland,’” Transformative Works and Cultures 12 (March 15, 2013), https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2013.0434. [↩]

- Sung-hee Park, “A Study on Domestic Inflow and Genre Specialization of BL (Boys’ Love) Adult Cartoon” (Seoul, South Korea, Sejong University, 2017). Over the past several years, specialized platforms and apps focused on BL content, such as BLancia, QToon, and Heavenly, have opened, and some of them ceased operations. [↩]

- Hyojin Kim, “Rethinking the Meaning of BL in the Feminist Era: Online Discourse on “Leaving BL” in Late-2010s Korea,” Feminism and Korean literature, no 47, pp. 197-227 (2019). [↩]

- Jungmin Kwon, Straight Korean Female Fans and Their Gay Fantasies (Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa Press, 2019). [↩]

This is really interesting! As a professional webtoon translator, I was wondering about this topic but in this country. I always found papers and investigation about BL/Yaoi but in Japan, but seems that the BL field in Korean is still young.

Thank you so much for the references and this great article.