The One Where the Media Scholar Watches the Most Popular Show on TV

Emily West / University of Massachusetts Amherst

The New York Times recently reported on the success of the CBS hit show NCIS (2003-present) on streaming platforms. Countering the conventional wisdom that streaming thrives on serialized entertainment that challenges audiences and deals in shades of grey, NCIS, and many episodic police procedurals like it, do very solid numbers in non-linear formats. The article reports, “In 2022, “NCIS” was more watched than “Ozark” and the film “Encanto,”” based on Nielsen estimates of streaming audiences.

This reminder of the evergreen popularity of not just police procedurals, but of NCIS in particular, has led to some scholarly soul-searching on my part. I am a media studies scholar who until last week had never watched an episode of the primetime hit NCIS, which stands for the military police service it depicts: Naval Criminal Investigative Service. No media scholar can watch everything, least of all in the age of “peak TV.” But NCIS is in its 20th season, debuting on September 23rd, 2003,[1] making it the 6th longest running scripted show on American television.

Even more than other long-running shows, like The Simpsons and Law & Order, NCIS has been a huge hit, for a long time.[2] It has been a top 5 show since Season 6, the number one most popular scripted television show since Season 7, and was the number one most popular program on television, beating even reality and sports phenomena like American Idol and NBC Sunday Night Football, in Season 10. That same year, it was the most watched television drama in the world.

And what do the journal articles, monographs, and edited volumes that focus on this long-running hit show explain, about its meaning, its reception, its staying power? While there are meaningful insights in the extant scholarship, these publications are very few in number. NCIS is hard to find in the titles of media studies publications in both books and journal articles.[3] I found only two publications with NCIS in the title, Thomas Gallagher’s “Sins of the Father: NCIS and the Family at Work” from 2016, and Molly Ann Magestro’s chapter on NCIS in a 2015 monograph on sexual violence in primetime drama. In a 2016 article Yvonne Tasker examines NCIS and The Blacklist as exemplars of how action, including the “action” of forensics and surveillance, has been hybridized with the crime genre.

Discussion of NCIS does appear in research on patterns in content across prime time (Bilandzic, Hastall & Sukalla 2017; Conrad-Perez, Chattoo, Coskuntuncel & Young, 2021; Garner, Kinsky, Duta & Danker 2012), within the broader genre of police procedurals (Applebaum 2019; Bernabo 2022; Dirikx, Van den Bulck & Parmentier 2012; Parrott & Parrott 2015; Tasker 2012), and in research examining the effects of viewing crime programming on attitudes towards violence and policing (Donovan & Klahm 2015; Hust, Marett, Lei, Ren & Ran 2015). Considering NCIS within a larger pattern of media messages makes sense within effects traditions, which argue that individual texts are less influential than the accumulation of media representations. Qualitative media scholars also favor analysis across texts, in order to establish ideological patterns in representation (Bernabo 2022; Lotz 2004). But even within this type of analysis NCIS is not included as part of the sample as often as its popularity might suggest. There’s room for establishing patterns across media and zeroing in on particularly popular texts. Certainly, other long-running shows like The Simpsons, Grey’s Anatomy, and fellow crime shows like Law & Order, CSI, and The Shield have enjoyed considerably more focused scholarly attention than NCIS.

Whether as an influence on audiences or an indication of what pleasures and worldviews they gravitate towards, this lacuna in critical scholarship about NCIS suggests that it is seen, broadly by the field, as too obvious or mainstream to warrant investigation. But interrogating the popular and demonstrating that it is never as simple as it seems is precisely at the heart of critical media studies and cultural studies’ projects.

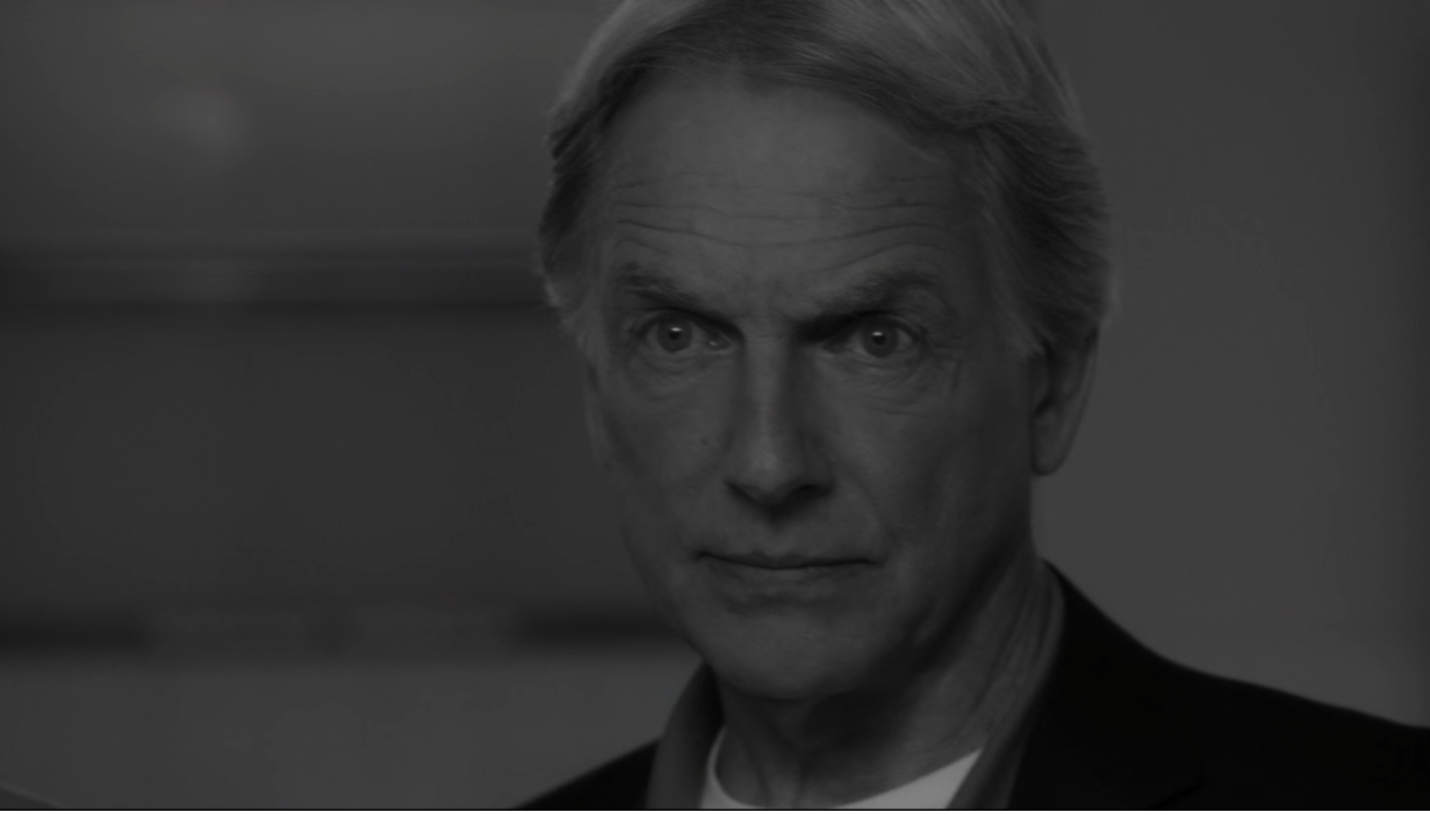

We should be clear-eyed about how the subject positions and tastes of media scholars, writ large, influence how we train our scholarly lenses. NCIS is broadcast television. It’s on CBS, and like the network as a whole skews to older, rural audiences. It’s conservative (I think it’s safe to assert). So what did I learn as I finally got around to watching the most popular show in America? That it’s a “feel-good” show about law enforcement. NCIS wraps societal violence, its investigation, and resulting punishments into a warm and fuzzy, light-hearted workplace drama that is pre-occupied with the inner lives and personalities of its ensemble cast to an extent reminiscent of soap opera. While soap operas are known for their lingering reaction shots on characters, NCIS plays with this convention with black and white stills that highlight a main ensemble character’s reaction to something dramatic or surprising (see Figure 4). This device illustrates how the driving force of the show is emotion and personality. The affective emphasis of the show helps explain (although not excuse) the way its frequently melodramatic plots are not overly invested in plausibility nor do they meaningfully grapple with the significant issues that the show’s premise brings into play—such as the impact of military service on mental health, sexual assault in the military, or what happens when police abuse their power. It’s jarring to see these themes embedded in a show whose vibe is what I would describe as, overall, cute.

The paucity of critical media scholars among the target audience for NCIS has likely contributed to its under-examination in the literature, a taken-for-grantedness that feels like a mistake when societal attitudes towards policing are such an urgent issue. In the wake of George Floyd’s murder by a Minneapolis police officer in May 2020 (and even before), public commentary as well as industry critique turned to the role that entertainment about policing has played over time in cultivating a deferential attitude among the public to law enforcement institutions that so regularly display the cruelty, authoritarianism, and impunity observed in Floyd’s murder—“copaganda,” it’s been coined. In this context, it would be valuable to have an in-depth examination of racial representation on the most popular show in America, where, just for starters, for many of its seasons the only African-American character in the ensemble plays the boss, with not a lot of screentime—a seemingly classic case of tokenism.

My argument is not against scholarly attention to fan favorites or “quality” entertainment or cutting-edge shows that push the boundaries of what can get made in commercial media and are meaningful to under-served audiences. Rather, it’s a reminder (very much including myself) to simultaneously keep our disciplinary eye on the popular mainstream, as part of our collective professional responsibility. We teach our students that ideology frequently works through its very taken-for-grantedness, becoming almost invisible as part of common sense. The longstanding popularity of NCIS even in a changing world and media landscape is a striking example of something that scholars should approach as a puzzle that requires theorization and explanation, rather than letting its ubiquity become part of the wallpaper.

Image Credits:

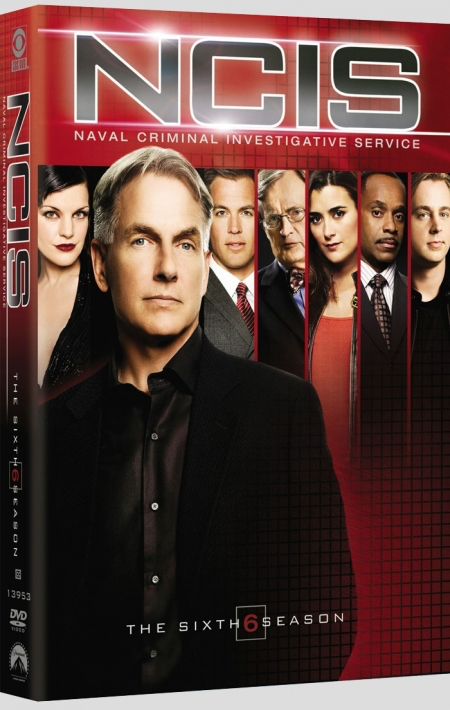

- Figure 1 – “DVD Ncis Season 6 Zone 1” by louisvolant is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

- Figure 2 – “nielsen” by mrmatt is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

- Figure 3 – “Police Show Logo” by BRICK 101 is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

- Figure 4 – Screenshot from Season 15, Episode 5, “Trapped,” of Mark Harmon as Leroy Jethro Gibbs.

Applebaum, Robert. (2019). “The Aesthetics of Terrorism and the Temporalities of Representation.” Contemporary Aesthetics, Special Volume 7. https://contempaesthetics.org/2019/10/31/article-876/

Bernabo, Laurena. (2022). “Copaganda and Post-Floyd TVPD: Broadcast Television’s Response to Policing in 2020.” Journal of Communication, 72 (4): 488–496. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqac019

Bilandzic, Helena, Matthias R. Hastall, and Freya Sukalla. (2017). “The Morality of Television Genres: Norm Violations and Their Narrative Context in Four Popular Genres of Serial Fiction.” Journal of Media Ethics, 32(2): 99–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/23736992.2017.1294488

Conrad-Perez, David, Caty Borum Chattoo, Aras Coskuntuncel, and Lori Young. (2021). “Voiceless Victims and Charity Saviors: How US Entertainment TV Portrays Homelessness and Housing Insecurity in a Time of Crisis.” International Journal of Communication 15: 22. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/16781

Dirikx, Astrid, Jan Van den Bulck, and Stephan Parmentier. (2012). “The Police as Societal Moral Agents: “Procedural Justice” and the Analysis of Police Fiction. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 56 (1): 38–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2011.651187

Donovan, Kathleen M., and Charles F. Klahm IV. (2015). “The Role of Entertainment Media in Perceptions of Police Use of Force.” Criminal Justice and Behavior, 42 (12): 1261–1281. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854815604180

Gallagher, Thomas. (2016). “Sins of the Father: NCIS and the Family at Work.” The Journal of Popular Culture, 49 (4): 875–896. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpcu.12434

Garner, Johny T., Emily S. Kinsky, Andrei C. Duta, and Julia Danker. (2012). “Deviating from the Script: A Content Analysis of Organizational Dissent as Portrayed on Primetime Television.” Communication Quarterly,60 (5): 608–623. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463373.2012.725001

Hust, Stacey J.T., Emily Garrigues Marett, Ming Lei, Chunbo Ren, and Weina Ran. (2015). “Law & Order, CSI, and NCIS: The Association Between Exposure to Crime Drama Franchises, Rape Myth Acceptance, and Sexual Consent Negotiation Among College Students.” Journal of Health Communication, 20 (12): 1369–1381. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2015.1018615

Lotz, Amanda D. (2004). “Using “Network” Theory in the Post-Network Era: Fictional 9/11 US Television Discourse as a “Cultural Forum”. Screen, 45 (4): 423–439. https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/45.4.423

Magestro, Molly Ann. (2015). ““She Got Herself Raped and Killed”: Victim-blaming and Silencing on NCIS. In Assault on the Small Screen: Representations of Sexual Violence on Prime Time Television Dramas. New York: Rowman & Littlefield.

Parrott, Scott, and Caroline T. Parrott. (2015). “Law & Disorder: The Portrayal of Mental Illness in US Crime Dramas.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 59 (4): 640–657. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2015.1093486

Tasker, Yvonne. (2016). Sensation/Investigation: Crime Television and the Action Aesthetic.” New Review of Film and Television Studies, 14 (3): 304–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/17400309.2016.1187027

Tasker, Yvonne. (2012). “Television Crime Drama and Homeland Security: From Law & Order to “Terror TV”.” Cinema Journal 51, (4): 44–65. doi:10.1353/cj.2012.0085

- NCIS is actually a spin-off of the show JAG, also a military-themed show dealing with law enforcement, that aired from 1995–2005. [↩]

- Its success led to three spin-off series: NCIS: Los Angeles (2009–2023), NCIS: New Orleans (2014–2021), and NCIS: Hawaii (2021–present). [↩]

- Based on searches in Google Scholar, Communication and Mass Media Complete, and WorldCAT. [↩]

Yes, that tracks with what I’ve seen so far on the show. Although I’d be interested to hear what fans, who have followed the show for longer, think as well. Thanks for your comment!