Were You Looking at the Woman in the Red Dress? The Male Gaze in The Matrix

Nicole Erin Morse / Florida Atlantic University

In my first column for Flow, I discussed how the Magic Mike franchise—which might appear to cater to heterosexual female desire—serves as a powerful demonstration of the persistence of the male gaze in popular cinema. Now, I want to look at another potentially counter-intuitive iteration of the gaze. This time, I’ll be arguing that the male gaze is interrogated and policed in the Wachowski sisters’ sci-fi blockbuster The Matrix (1999). This claim is only potentially counter-intuitive, for although The Matrix may appear at first glance to be addressed primarily to teenage boys, it is part of a filmography that Cael Keegan has shown is powerfully and compellingly trans, queer, and feminist.[1]

Through close reading a sequence from The Matrix, I show how the film examines, mocks, and punishes the male gaze. Moreover, it does so through exploiting the very techniques that produce the male gaze in cinema: shot reverse-shot editing patterns that can be used to align the camera and the audience’s perspective with the diegetic look of the male character.[2] As a result, the film offers a feminist cinematic experience produced through, rather than against, the formal strategies of dominant, popular cinema. It also reveals the crucial importance of form in structuring—and deconstructing—the male gaze.

The Matrix accomplishes this through a sequence toward the middle of the film that takes audiences from the reality of the rebel ship to a training simulation built to resemble the oppressive artificial world that is the film’s namesake: the matrix. This sequence introduces the protagonist Neo to the infamous “woman in a red dress,” a computer simulation designed to be maximally appealing to heterosexual male desire. But this seductive character, reminiscent of Marilyn Monroe, isn’t where the sequence begins. Instead, it begins when Trinity drops off some food beside the sleeping Neo.

Initially, the sequence uses formal techniques to reveal how the male gaze is structured and to convey its disquieting sadism. Trinity leaves Neo’s room, deep in thought. As she closes the door, a shot framed from behind Trinity reveals that she is being watched by Cypher. Although the camera isn’t aligned with Cypher’s perspective, this moment encapsulates a power dynamic that is central to the male gaze: the fiction that the actress on screen is unaware of being watched by the character within the film or the audience outside the film.[3] When the looks of the character, camera, and spectator are aligned, this pretense that the actress is not aware that she is being watched permits the audience to indulge in the pleasures of sadistic voyeurism.

In this case, however, Cypher isn’t an ideal identificatory figure for the audience. Even at this point in the narrative, he is far less sympathetic than Trinity. Moreover, with the camera behind her, the audience is aware of—but not aligned with—his look.

Then Trinity notices Cypher, and her severe, unfriendly facial expression validates our sense that something about his behavior is off, before a relatively conventional shot reverse-shot dialogue sequence begins.

Cypher continues to act in ways that reinforce the sense that he is sexualizing Trinity. But the camera does not collude with his look; instead, as Cypher moves toward Trinity, invading her personal space, the shot reverse-shot dialogue transforms into a pattern of complementary two shots. Rather than looking with Cypher, the audience looks at Cypher as he looks at Trinity.

This scene is clearly about looking. And its critique of the male gaze becomes even more overt as Trinity leaves the scene. With the camera behind her, Trinity crosses the screen and walks out of the frame, leaving Cypher alone, staring after her.

Since she is no longer looking back at Cypher, the off-screen Trinity might seem to return to the position she occupied at the beginning of the scene: the object, not the subject, of the look. As the camera holds on Cypher, his eyes move up and down, presumably tracing Trinity’s form as he watches her leave.

This shot, which shows the male character looking, creates a sense of expectation that the following show will show the audience what he sees. After all, that is the classic grammar of the male gaze—and a fundamental building block of film syntax in general. A character looks, and the next shot shows what the character sees.

But The Matrix doesn’t deliver the expected image of Trinity. Instead, the sequence transitions to a simulated street by cutting to the image of a red street light warning pedestrians not to proceed.

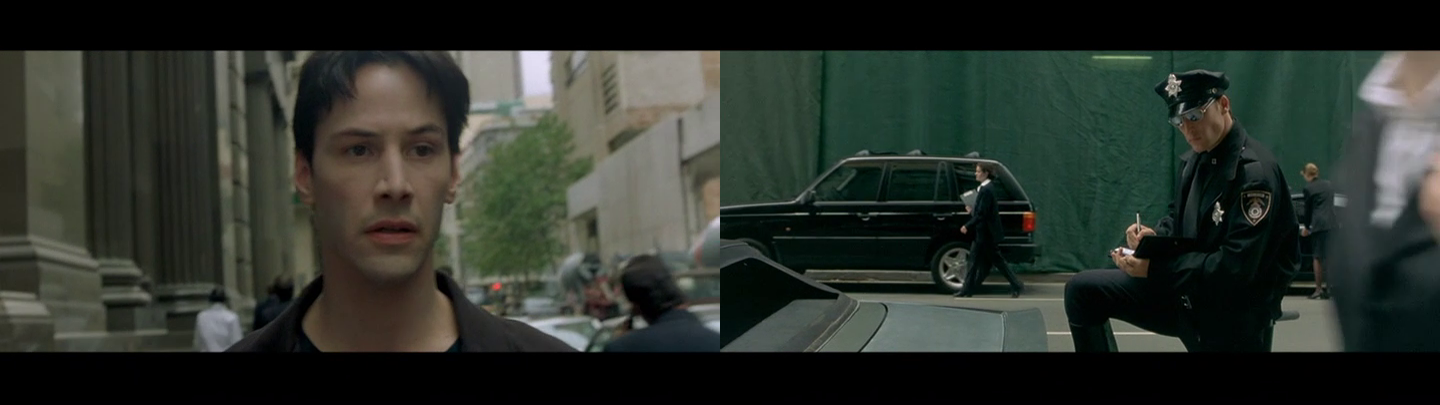

After this playful visual trick critiques Cypher and the male gaze, the red silhouette quickly turns green as Neo follows Morpheus across a street within the simulated world. The camera work is chaotic as Neo struggles to keep up with Morpheus amid the jostling crowd. But it becomes slower and steadier twice—each time, using shot reverse-shot editing to show Neo looking at a figure who looks back at him.

First, Neo locks eyes with a police officer.

The shot of the police officer tracks right while holding the officer in the center of the frame, moving with Neo as he walks, aligning the three looks of the camera, audience, and character. As the sequence returns to Neo, this shot reverse-shot structure would be a paradigmatic example of the male gaze—except its object is a man, and moreover, a representative of the law.

Moments later, however, this same pattern is repeated, but with a seemingly more appropriate object of the gaze. Once again, Neo looks, and the frantic rhythm of the scene is interrupted by a shot that allows the audience to see what he sees in slow motion: a blonde bombshell in red.

As Neo turns to watch her walk away, Morpheus asks Neo if he was paying attention, or if, instead, he was “looking at the woman in the red dress.” Embarrassed to be caught in this moment of voyeurism, Neo tries to respond, but Morpheus interrupts him and tells him to “look again.”

The cut reveals that the woman in the red dress was actually Agent Smith all along, not a sexy screen siren but, similar to the police officer, another representative of the law. The symbolism here is almost comically on the nose, for the male gaze is designed to diffuse the anxiety provoked by the image of the castrated woman. Here, the red silhouette and red dress evoke the bloody specter of castration and are eventually superseded by a phallic symbol: the gun.

Like the earlier cut, there’s a playfulness to this moment generated from the audience’s knowledge of how the male gaze is supposed to work. When we see the male character looking, we expect to see what he sees. We anticipate indulging in the visual pleasures of narrative cinema.

Instead, The Matrix gives us something very different—a set of symbols deconstructing this formal device and warning us to think carefully about how we look.

Image Credits:

- A classic screen siren distracts the protagonist in The Matrix (1999) (author’s screen grab).

- Something catches Neo’s attention, and the film cuts so we see what he sees (author’s screen grab).

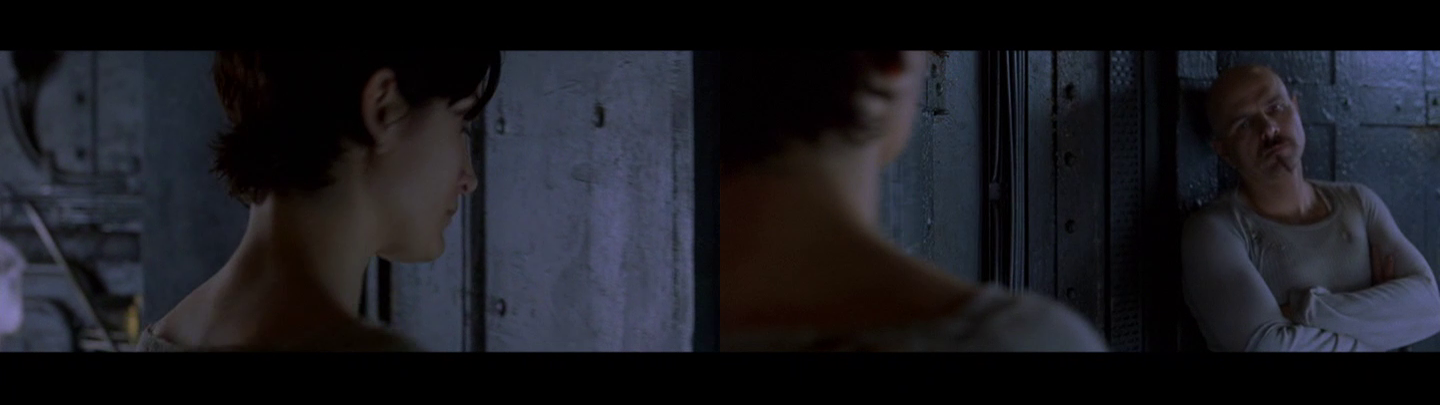

- Trinity closes the door, revealing Cypher (author’s screen grab).

- A reverse shot shows Trinity noticing Cypher watching her (author’s screen grab).

- Cypher and Trinity speak, as the scene cuts back and forth between them (author’s screen grab).

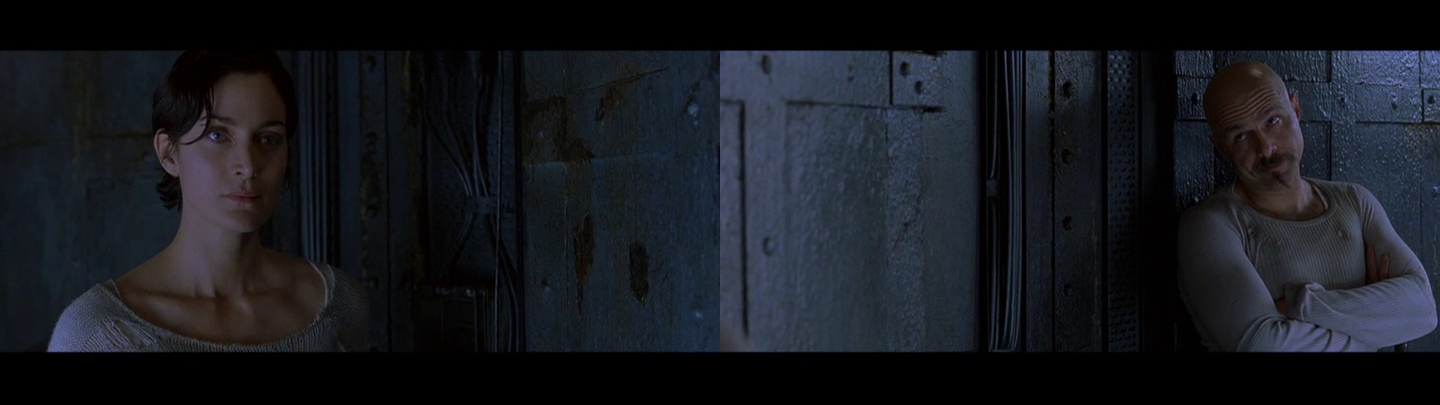

- Cypher and Trinity continue speaking in two shots (author’s screen grab).

- Cypher is in focus as Trinity’s exit functions as an in-camera wipe effect (author’s screen grab).

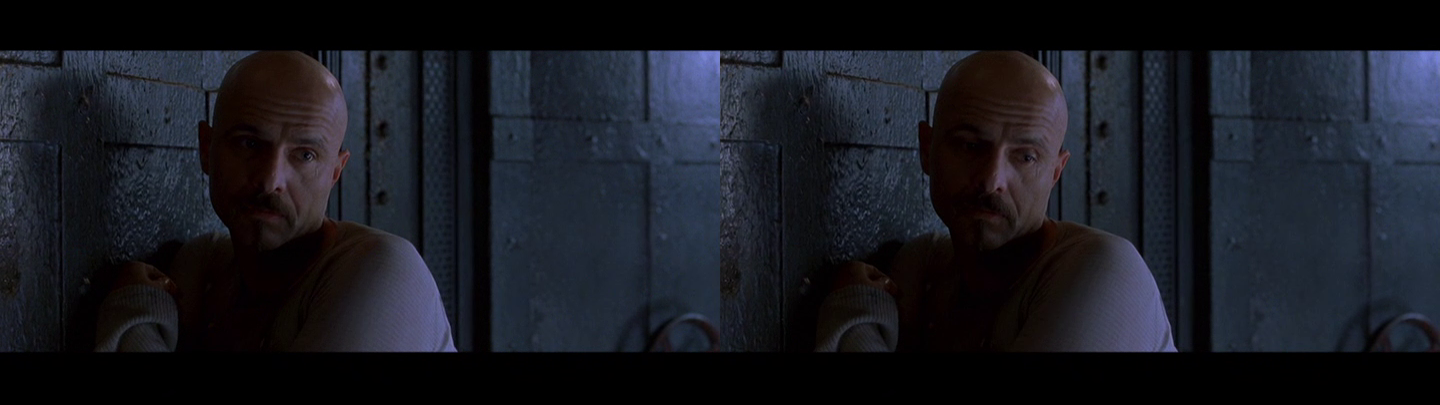

- Cypher’s “elevator eyes” emphasize how he objectifies Trinity (author’s screen grab).

- A false eyeline match suggests that this symbol for “stop” is what Cypher sees (author’s screen grab).

- Neo looks, and in the next shot the police officer returns his look (author’s screen grab).

- The woman in the red dress walks past Neo, also locking eyes with him (author’s screen grab).

- Neo looks, and the Agent’s gun points directly at the camera, aligning the three looks (author’s screen grab).