From “Relevance” to “Reckoning” or, Channeling Black Lives Matter on TV — Part One

Brandy Monk-Payton / Fordham University

On July 30, 2020, cultural critic Wesley Morris opined that “The Reconciliation Must Be Televised.” The New York Times piece suggested that the United States must confront and atone for the sins of slavery and enduring systemic racism through a truth and reconciliation months-long forum broadcast as must-see television. Morris says that the event must be televised, both with live and recorded elements, on all available channels from NBC to Netflix. If a national therapy session is in order, it must also include beloved TV personalities like Oprah Winfrey who will guide viewers at home not just to look and listen, but to witness. The widespread transmission could be a fruitful endeavor, like the groundbreaking mini-series Roots (ABC, 1977) before it, to attend to this new yet centuries old “Moment,” this present movement for black lives.

For almost ten years as both a scholar and spectator, I have been interested in how the medium of television, in its claims to immediacy and relevance, navigates the current climate of anti-black violence. The murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Minnesota on May 25, 2020 and the global protests that summer solidified television’s still lucrative role in creating and disseminating messages around social and political unrest. As I asked that summer, “What do we want and need from television right now? What are the limitations and possibilities of the medium in addressing and redressing anti-black violence?” As a commercial medium, TV has seemed to shift from the discourse of promoting racial “relevance” to that of practicing an active “reckoning” with race at the level of the industry, text, and audience. This is the first of two columns that I will devote to exploring what I am conceptualizing as Black Lives Matter television or “BLM TV.”

The term BLM TV explicitly calls to mind Sasha Torres’s (2003) rendering of “King TV” to denote the cycle of non-fictional and fictional programming connected to the beating of Rodney King and the subsequent uprisings in Los Angeles in 1991. These texts, from news coverage to drama series like L.A. Law (NBC, 1986-1994) and Doogie Howser, M.D. (ABC, 1989-1993), worked together to construct ideas around TV’s mediation of the racial politics of law and order during the early 1990s. The infamous video footage of King being pummeled on the ground by law enforcement circulated on screen in a similar fashion to contemporary cell phone recordings of Black individuals like Michael Brown and Philando Castile shot and slain by police officers. In my “Television, Race, and Civil Rights” undergraduate class, we discuss the resonances between journalistic accounts of rebellion connected to racial violence from the early nineties to our current demonstrations thirty years later. In the rest of this piece, I want to analyze not news reporting but the broader formation and significance of BLM TV. The cycle begins in 2013, the year that the hashtag #blacklivesmatter became a rallying cry in response to the acquittal of George Zimmerman for the killing of Trayvon Martin. Since then, television programs have remarked on this history of violence in explicit and implicit ways. It is important to note that not every program that centers black people today can and should be considered Black Lives Matter TV. Rather, BLM TV is an amalgamation of non-narrative and narrative approaches to interrogating structural racism and anti-blackness on- and off-screen.

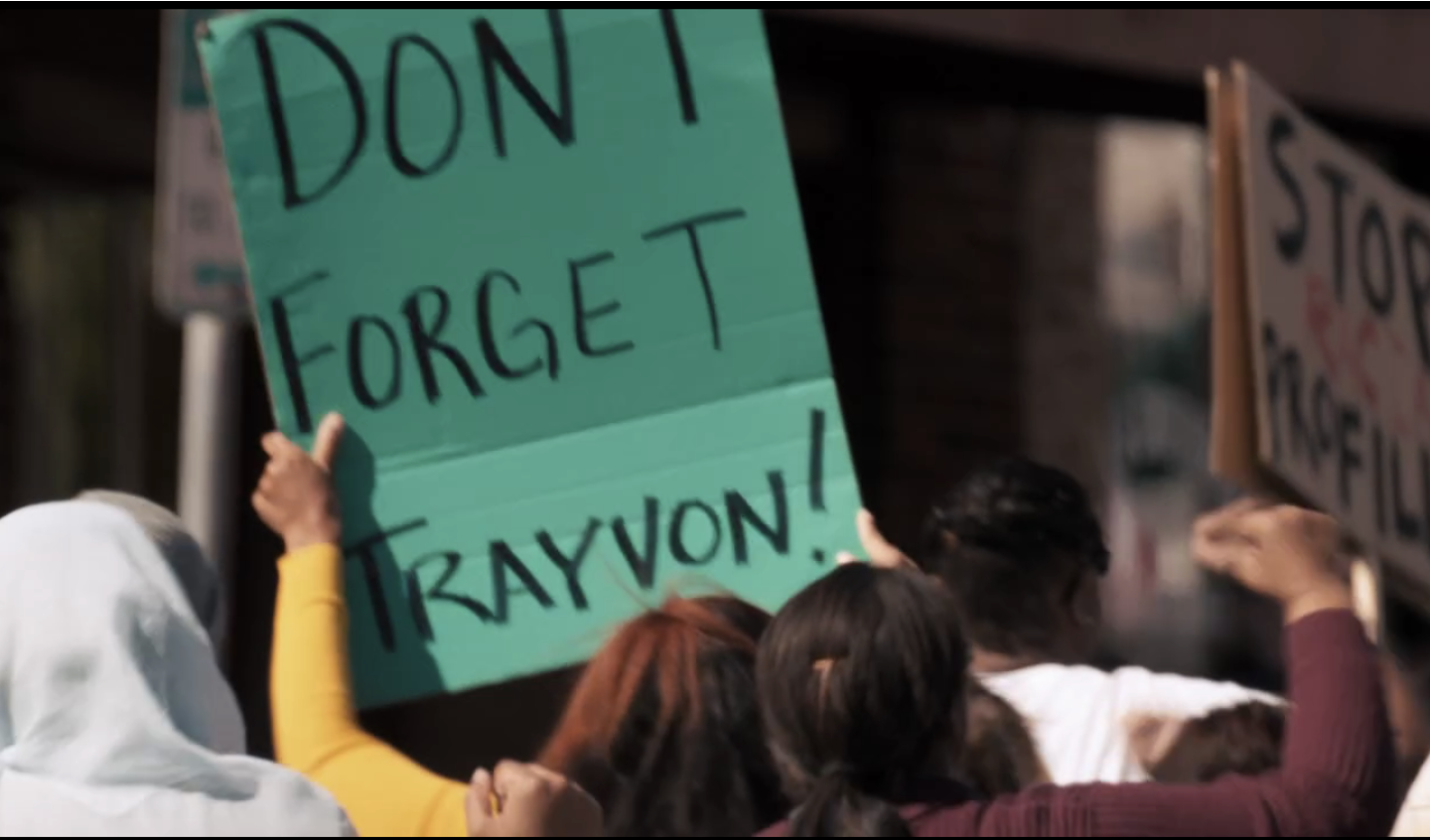

First, BLM TV includes, but is not limited to, the variety of series that feel compelled to produce the “very special episode” (VSE) on police brutality that is common nowadays. The VSE can be an efficient and effective way to contend with crisis with its pedagogical purpose. In their new edited collection, Very Special Episodes: Televising Industrial and Social Change, Jonathan Cohn and Jennifer Porst (2021) argue that such episodes have “become an important way for the television industry to respond to and shape social change, cultural traumas, and industrial transformations.” (3) Fittingly, it was Law and Order: Special Victims Unit (NBC, 1999-present) and its “ripped from the headlines” logic that first depicted a Black Lives Matter rally in the aftermath of the killing of Trayvon Martin in 2013. After Brown’s death in Ferguson, Missouri, Scandal (ABC, 2012-2018) responded with “The Lawn Chair” in which Olivia Pope, the black female professional fixer, could not “fix” state-sanctioned violence against African Americans. The 2015 episode represented one instance in which showrunner Shonda Rhimes felt compelled to respond issues of racial injustice, with the writer of the episode Zahir McGhee stating that Rhimes even came up with the fictional protestors’ chant: “Stand up, fight back, no more black men under attack.” Indeed, as Jade Petermon and Leland Spencer have argued: “BLM has reached a level of cultural familiarity such that drama television series on networks like ABC devote entire episodes to the movement…drama series’ representations of BLM matter in the ways they narrate the movement’s politics and its history.” (340) They further state that “Mainstream representations of BLM often erase the identities of the many queer Black women who have been foundational to the movement.” (352) Thus, the stories that these popular programs tell about BLM in particular have been criticized in their appropriation and exploitation of the cause, which also serves to obscure the fundamental intersectionality of its origins indebted to the activist work of Alicia Garza, Opal Tometti, and Patrisse Cullors.

BLM TV exists across different genres of programming on broadcast, cable, and premium channels, as well as streaming platforms. In her interview with Kenya Barris, Christine Acham (2018) discusses how the current social and political environment impacted the sitcom Black–ish (ABC, 2014-present), even resulting in a second season episode called “Hope” in which the Johnson family reacts to the non-indictment of a police officer accused of killing a young black man. I would argue that Academy Award winner John Ridley’s foray into prestige television American Crime (ABC, 2015-2017) is the first series that is wholly in and of the Black Lives Matter movement. During the initial development of the program, Ridley recounts then-President of ABC Entertainment Group Paul Lee approaching him to create a “bold” project in the wake of Trayvon Martin. Other programs like Reggie Rock Bythewood and Gina Prince-Bythewood’s short-lived police drama Shots Fired (Fox, 2017) and the limited series Seven Seconds (Netflix, 2018) soon followed in their depictions of black communities disrupted by the violent behavior of corrupt law enforcement officials.

Programs that enter into a conversation around BLM do not have to be premised on policing and police brutality. Atlanta (FX, 2016-present) is what Taylor Nygaard and Jorie Lagerwey define as a “diverse quality comedy” that plays with both realism and surrealism in black urban culture. Its characters’ fates are attached to the “intractable part of the racist governance of contemporary America.” (160) A legal drama like The Good Fight (CBS All Access, 2017-2020; Paramount+, 2021-present) tackles the racial politics in the workplace of an all-black law firm in the Trump era. In reality television, BLM TV manifests with renewed calls for diversity, equity, and inclusion both behind and in front of the camera. The debacle surrounding the first black Bachelor, Matt James, compelled participants of color to speak out against the franchise’s racial biases and discrimination, which ultimately resulted in the removal of longtime TV matchmaker Chris Harrison as host. The most recent season of Big Brother (CBS, 2000-present) follows black contestants who have successfully strategized to form an alliance—aptly titled the “Cookout”—in order to ensure the first black winner of the competition. Experimental programs like Terence Nance’s collaborative artistic endeavor Random Acts of Flyness (HBO, 2018-present) in its desire to “shift consciousness” provides a different contour to the matter of black life.

The branding of BLM TV on streaming platforms occurs through algorithmic logics; categories dedicated to purported anti-racist content frame viewer encounters with blackness by catering to the popular notion of “wokeness.” Laura Irwin and Ralina L. Joseph explain in a previous Flow column that Hulu’s program aptly titled Woke (2020-present) about a black male cartoonist who awakens to the systemic use of excessive force after his own incident with the cops “falls flat, succumbing to the burden of representation” in its navigation of “heightened expectations” on the part of some audiences for black art to index astute radical politics. They rightly assert that there is a disconnect between the promise of such content’s engagement with social justice and what it actually delivers. Creatives and their politically aware programming increasingly culled for the BLM TV market can be didactic and outright offensive. Look no further than the ill-conceived horror program Them (Amazon Prime, 2021), which still reproduces a kind of white imagination of black terror and suffering under the guise of critical commentary.

The messages that are conveyed in the most generative of such BLM TV programs are not solely focused on grappling with the material and psychic violence of anti-black racism. Rather, they also have the tendency to combine expressions of trauma and joy, striving to depict the complexity and fullness of black experience. In this way, there is a degree of commitment to the goal – if perhaps rarely achieved – of cultivating what Tina M. Campt (2021) has described as a “black gaze.” By this, she means not just a black perspective, but an attentiveness to a “politics of looking with, through, and alongside another…a gaze that requires effort and exertion.” (8)

Finally, I suggest that BLM TV is fundamentally concerned with the idea of reparations. Previously, I have written about televisual reparations as an ontological question for the medium that has aesthetic, political, and ethical implications with respect to racial blackness. Sometimes the insistence on compensation is literalized in storytelling: Sci-fi/fantasy series Watchmen (HBO, 2019) named them “Redfordations”; and, indeed, the first episode of Fox’s new family melodrama Our Kind of People executive-produced by Lee Daniels is actually titled “Reparations.” We might also think of the 2018 Emmy Awards ceremony, in which comedian co-host Michael Che participated in a Saturday Night Live-esque recorded sketch to give out what he called “Reparation Emmys” to African American small screen legends that have gone largely unnoticed by the TV industry. Some of the icons lost to mainstream (read: white) memory who appear in the sketch include Marla Gibbs, Jimmie Walker, and Jaleel White. The final conversation between Che and now-deceased Black actor John Witherspoon brings up the often-cited idea that reparations is defined by the promise of receiving “40 Acres and a Mule”—the payment of property (land and livestock) that would have gone to former slaves after their emancipation. The sketch fantasizes how Che might right the wrongs of the Television Academy with respect to racial inclusion. Here, there are the beginnings of a mandate for TV to pay its debts—at the level of production, distribution, exhibition, and overall recognition—to black performers, producers, and programs. The rhetoric of reparations has even caught on to the upper echelons of black media making: founder of Black Entertainment Television (BET) and black billionaire Robert L. Johnson also recently came out in support of the economic demand.

What I have just outlined above is not an exhaustive list of the characteristics of the BLM TV phenomenon, yet I hope this brief entry provides a starting point for how we might think about the function of Black Lives Matter for television culture.

Image Credits:

1. Still from American Crime Season 1, Episode Eight (author’s screen grab)

2. Black Lives Matter protest at CNN Headquarters in Atlanta, GA on May 29, 2020

3. Still from American Crime Season 1, Episode Eight (author’s screen grab)

4. Still from the 70th Primetime Emmy Awards on September 17, 2018 (author’s screen grab)

References:1. Campt, T. (2021). A Black Gaze: Artists Changing How We See. MIT Press.

2. Cohn, J. and Porst, J., Eds. (2021). Very Special Episodes: Televising Industrial and Social Change. Rutgers University Press.

3. Irwin, L. & Joseph, R. (February 3, 2021). “Watching Woke: An Exercise in Restraining Our Burden of Representation.” Flow Journal. Retrieved from https://www.flowjournal.org/2021/02/watching-woke/

4. Monk-Payton, B. (2017). Televisual Reparations. Film Quarterly, 71(2), 12-18.

5. Nygaard, T. and Lagerwey, J. (2020). Horrible White People: Gender, Genre, and Television’s Precarious Whiteness. New York University Press.

6. Petermon, J. & Spencer, L. (2019). Black Queer Womanhood Matters: Searching for the Queer Herstory of Black Lives Matter in Television Dramas. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 36(4), 339-356.

7. Torres, S. (2003). Black, White, and in Color: Television and Black Civil Rights. Princeton University Press.