On the (In)Visibility of Female Gamers

Amanda C. Cote / University Of Oregon

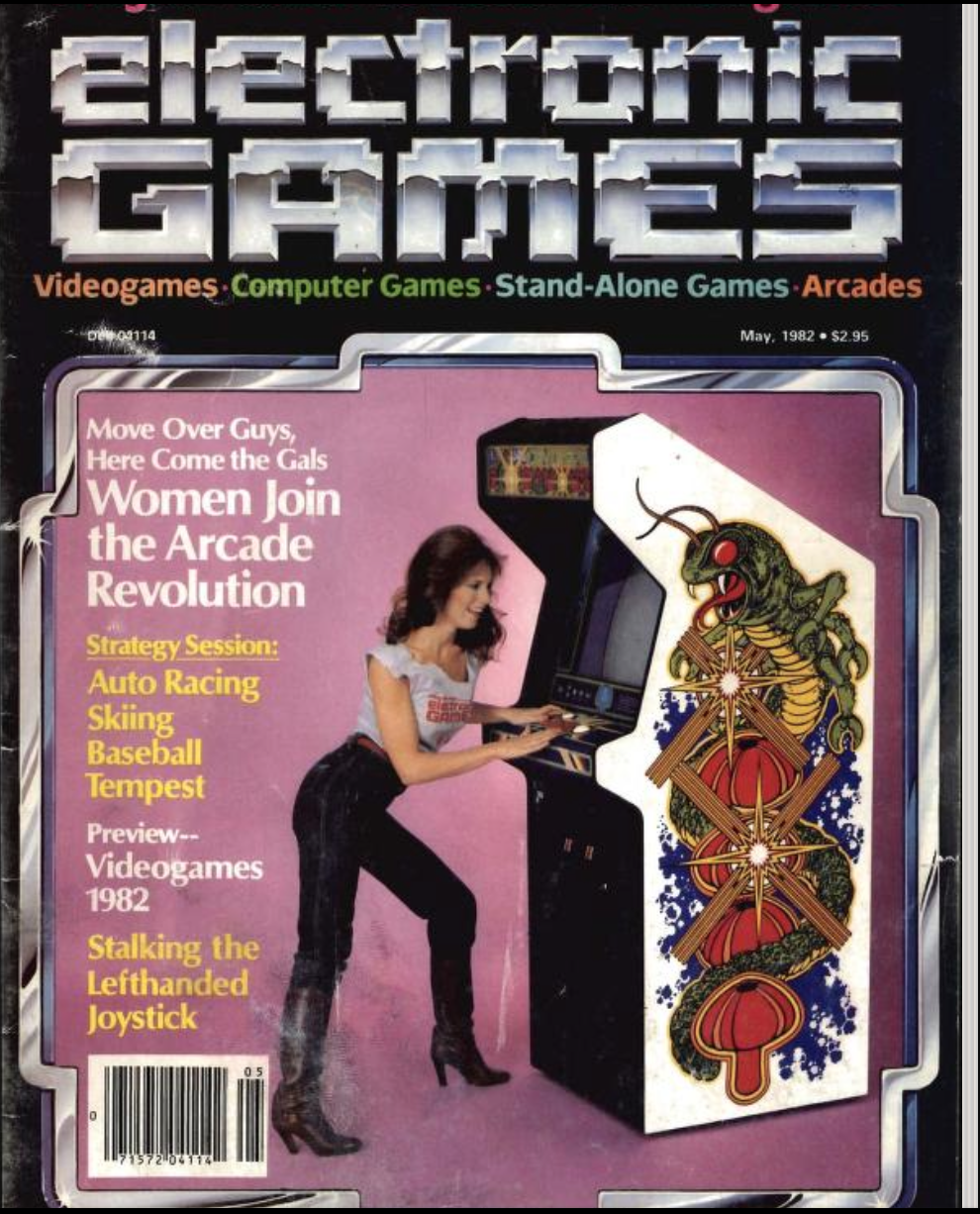

Recently, we’ve seen almost endless articles trumpeting the rise of the female gamer. From major news outlets like The Guardian, Forbes, and The Washington Post to game and tech publications like Venture Beat, the fact that women make up approximately half of all gamers seems to be everywhere. When we look back at game history, however, we can see similar narratives occurring semi-regularly. For instance, a 2000 CNN article proudly announced that women outnumbered men in online gaming spaces, while the May 1982 issue of Electronic Games declared “Move Over Guys, Here Come the Gals!”

Why are female gamers perpetually a surprise? How can we theorize their continual representation as “new” or unusual? While many researchers, myself included, have done a great deal of work on gaming and gender, this article proposes that our ongoing research could benefit from using the (in)visibility framework growing in popularity in sociology.[1] To advance this argument, I will first lay out what the (in)visibility framework entails and how it fits ongoing findings from game studies. I will then start to draw connections between games and other areas of (in)visibility research to outline the benefits of greater cross-pollination. Overall, this article is an exploratory investigation of how the (in)visibility framework could strengthen media audience research to overcome perpetual cycles of novelty, surprise, and dismissal.

(In)Visibility as a Framework

What does it mean to be visible? We often think of visibility as a good thing, a goal to be obtained. Marketing, public relations, or even political/activist campaigns often strive to “increase visibility” for a product or cause. Media studies scholars push for greater representation of diverse groups to make more people and perspectives visible in popular culture. And, of course, the rise of social media influencing, from Instagram to TikTok, rests on carefully curated forms of visibility. The Internet is packed with guides promising to help users gain visibility by strategically manipulating search terms and algorithmic rankings on these platforms.

At the same time, sociology’s (in)visibility framework suggests that visibility is not inherently positive. Rather, visibility articulates with existing power structures to be disempowering for some and empowering for others (e.g. Settles et al., 2019). Marginalized individuals, for instance, face invisibility when their contributions to an organization, community, or culture are overlooked—as, we could argue, has been the case with female gamers. For members of the dominant or majority group, however, invisibility can be a sign of power; when one is already accepted as belonging in a particular context, one does not need to be made visible. Lewis and Simpson (2010) illustrate this through a vocational example, highlighting how male managers “evade scrutiny and interrogation” with regards to their gender while female managers are “‘marked’ as gendered Other and have to work hard to manage both gender and occupational identity” (p. 2).

Visibility is also differently empowering based on these asymmetries. When one is normative for a particular context, one’s group or social identity is invisible or unmarked. This allows one to become visible as an individual. “Successes of privileged group members are therefore attributed solely to their personal efforts and characteristics (e.g., intelligence, hard work), and because they are not subject to heightened surveillance, their failures and transgressions are often invisible” (Buchanan & Settles, 2019, p. 3). Marginalized individuals, on the other hand, become visible predominantly through their axes of difference from the norm. As such, their actions, behaviors, successes, and failures can come to represent their entire group, rather than themselves as individuals. Further, their divergence from the norm risks marking them as hypervisible, subjecting them to increased scrutiny, judgment, or exclusion from others (Brighenti, 2007).

Finally, because existing power structures set the conditions of (in)visibility, marginalized individuals often have little control over their degree of visibility (Brighenti, 2007; McCluney & Rabelo, 2019; Settles et al., 2019). While many attempt to influence how others view them through impression management strategies (e.g. Bennett et al., 2019; Fernando et al., 2019; Roberts et al., 2014), these are often individualistic rather than collective. Therefore, they allow marginalized individuals to manage and work within existing systems of (in)visibility, but they do little to affect the underlying power structures that shape these forces in the first place.

(In)Visibility in Gaming

In gaming, where the normative player is still young, White, and male (among other characteristics), marginalized players, such as women, LGBTQ+ individuals, and players of color, are often encouraged to make themselves more visible, to combat stereotypes and show game companies and communities that they are meaningful audiences. Many visibility efforts exist in gaming to draw attention to how players and communities are already more diverse than stereotypes suggest.

At the same time, many of the female gamers I have spoken with for research revealed that rendering their identity as female gamers visible—through the use of voice chat, for instance, or through their physical presence in a game store—meant they instantly became hypervisible; others in the space would single them out for extra attention. This attention could be positive or negative in intent, but regardless of tenor, it would mark the female gamer as unusual, abnormal, or out of place. As my participant Helix told me during interviews for my recent book Gaming Sexism, being a female gamer is “like wearing a Halloween costume when most people aren’t, to work or to class or something. You’re not doing anything against the rules and a lot of people will think you’re cool for doing it, but other people will judge you and look down on you—and EVERYONE will notice you.” Thus, female gamers become trapped in (in)visibility’s double bind. On the one hand, their difference from the norm serves to minimize their presence and contribution to game communities. On the other hand, it subjects them to greater scrutiny and pressure.

Many female players opted to hide their gender to avoid this attention. The strategic management of (in)visibility was thus a way for female gamers to try to regain control or power in the face of challenges, and it correlates well with the impression management strategies (in)visibility researchers have discovered in sociology. Like those strategies, however, remaining invisible is at best an individual protection, doing little to change the overarching power systems that structure visibility in the first place. Other game researchers have found similar results. For instance, when large game publisher Blizzard Entertainment proposed a “RealID” system, which would link game identities to offline ones in an attempt to decrease toxic behavior, players protested extensively, arguing this policy would decrease their control over when, how, and to whom they revealed their identity (Albrechtslund, 2011). They were also specifically concerned for marginalized players, for whom invisibility could be a form of protection. In the face of player protests, Blizzard opted to make RealID voluntary, not mandatory. The unanswered question, of course, is if this decision prioritized short term, individual protection over long-term cultural and structural changes.[2]

The Benefits of Cross-Pollination

My research into (in)visibility frameworks is nascent, but even these small examples show how this approach offers many fruitful opportunities for both theorizing gaming and connecting to other fields.

Through greater cross-pollination between media and sociological studies of in(visibility), we can first and foremost dismiss the idea that issues in games don’t matter because they’re “just games.” Gaming is far from the only space in which individuals have to battle the competing pressures of (in)visibility. A growing body of organizational and vocational research also engages with how identity characteristics like race and gender influence one’s (in)visibility and power. In 2019, for instance, the Journal of Vocational Behavior published a special issue on “Managing (in)visibility and hypervisibility in the workplace” (Buchanan & Settles, 2019). The issue’s twelve articles cover fields from engineering to music composition to cleaning and housekeeping, exploring how gender, race, and sexuality, as well as the intersections between these, all affect individuals’ lived experiences of visibility. Issues of (in)visibility, inclusion, exclusion, and power permeate many aspects of society and culture, and addressing these in gaming can only strengthen efforts in other areas.

Further, as stated above, individuals facing (in)visibility challenges currently manage these largely on their own. Greater attention to systemic responses across different fields could allow these to propagate more widely and increase their efficacy. Finally, recognizing that the root of (in)visibility issues is the same regardless of area (persistent, unequal structures of powers), managing this issue on multiple fronts simultaneously can hopefully encourage greater, faster movements towards equity.

The battle over (in)visibility is only likely to increase in gaming spaces. The rise of live-streaming services like Twitch, for instance, bring a unique set of challenges that marginalized gamers have to manage (see Uszkoreit, 2018). The increasing popularity of esports—competitive multiplayer gaming—also places more gamers in the spotlight, if they want to compete at high levels. To steal a line from Brighenti (2007), then, “the argument developed here is meant to show that the issue of visibility can be treated as a single field, and that there would be much to be gained by taking such a new viewpoint.” (p. 325).

Acknowledgements: Thank you to Dr. Wai Yen Tang for directing me to the Journal of Vocational Behavior’s special issue on (in)visibility and to Dr. Maxwell Foxman for providing feedback on an early draft of this article.

Image Credits:

- A 2014 PBS story announces, “Adult female gamers have unseated boys under the age of 18 as the largest video game-playing demographic in the U.S.” (Pullian-Moore, 2014). Similar articles started appearing in other publications around this time and have persisted to today.

- The cover of Electronic Games’ May 1982 issue, with the feature article “Women Join the Arcade Revolution.” Image via the FEMICOM Museum. The full feature article is available on the Old Game Mags Tumblr.

- A Google search for “social media visibility” returns over 5 million hits for videos alone. Screenshot collected May 2021.

- The Esports Observer launched their “Visibility In Esports” section in 2019 to highlight women’s contributions to esports. Screenshot of the column’s landing page as of May 2021.

- Female Twitch streamers often discuss visibility’s benefits and challenges, as in this piece from The Guardian.

- Albrechtslund, A.-M. (2011). Online Identity Crisis: Real ID on the World of Warcraft Forums. First Monday, 16(7). https://journals.uic.edu/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/3624/3006

- Bennett, D., Hennekam, S., Macarthur, S., Hope, C., & Goh, T. (2019). Hiding gender: How female composers manage gender identity. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 113, 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.07.003

- Brighenti, A. (2007). Visibility: A category for the social sciences. Current Sociology, 55(3), 323–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392107076079

- Buchanan, N. T., & Settles, I. H. (2019). Managing (in)visibility and hypervisibility in the workplace. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 113, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.11.001

- Cote, A. C. (2018). Curate Your Culture: A Call for Social Justice-Oriented Game Development and Community Management. In K. L. Gray & D. J. Leonard (Eds.), Woke Gaming: Digital Challenges to Oppression and Social Injustice (pp. 193–212). University of Washington Press.

- Fernando, D., Cohen, L., & Duberley, J. (2019). Navigating sexualised visibility: A study of British women engineers. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 113, 6–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.06.001

- Lewis, P., & Simpson, R. (2010). Introduction: Theoretical Insights into the Practices of Revealing and Concealing Gender within Organizations. In P. Lewis & R. Simpson (Eds.), Revealing and Concealing Gender: Issues of Visibility in Organizations (pp. 1–22). Springer.

- McCluney, C. L., & Rabelo, V. C. (2019). Conditions of visibility: An intersectional examination of Black women’s belongingness and distinctiveness at work. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 113, 143–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.09.008

- Roberts, L. M., Cha, S. E., & Kim, S. S. (2014). Strategies for managing impressions of racial identity in the workplace. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 20(4), 529–540. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037238

- Settles, I. H., Buchanan, N. T., & Dotson, K. (2019). Scrutinized but not recognized: (In)visibility and hypervisibility experiences of faculty of color. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 113, 62–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.06.003

- Uszkoreit, L. (2018). With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility: Video Game Live Streaming and Its Potential Risks and Benefits for Female Gamers. In K. L. Gray, G. Voorhees, & E. Vossen (Eds.), Feminism in Play (pp. 163–182). Springer.

- Various forms of visibility research exist across many fields. For instance, visual culture studies is attentive to how power structures visuality/ways of looking (e.g. Mirzoeff, 2011), modern media landscapes encourage what Banet-Weiser (2018) refers to as an economy of visibility, and visibility politics undergird many activist movements, such as the fight for LGBTQ+ civil rights. This article focuses on the sociological in(visibility) framework not to replace these other traditions, but as a possible means to draw many of them together, given its breadth and attentiveness to both individual experiences and institutional power structures. [↩]

- Forcing marginalized players to reveal themselves is of course not a solution to in-game toxicity. But only relying on individualized strategies is also what my participant Emily described as “a Band-Aid” rather than a cure. More structural changes are needed to address inequality in the long term. See also: Cote, 2018. [↩]

Great essay, Amanda! I didn’t realize your book was out – congrats, I will get my copy today.

Really interesting use of the “(in)visibility” framework here; appears to suit your research and analysis very well, and offers real insights into the issues regarding gender and gaming that you explore so well. Really interesting work.