A Look into Digital Blackface, Culture Vultures, & How to Read Racism like Black Critical Audiences

Lando Tosaya and Ralina L. Joseph / University of Washington

Part three of this Flow series, a look into Digital Blackface, coalesces our arguments from parts one and two. Part one addresses how the NBA as a franchise performs performative activism, while individual players such as Jimmy Butler toe the line between activism and performative activism. Moultrie and Joseph describe “a simultaneous distance from and proximity to power,” that blurs activism, the intentional disruption of oppressive systems of power,[1] and performative activism, a mere guise of such disruption towards change-making,[2] as the means to speak back to hypervisible murders of countless Black bodies replayed constantly across the media. Part two of this Flow series extends this blur to Black representation, which is not a paradox of “good” versus “bad” (just as part one does not position “good activism” against “bad performative activism”) but a dialectic, particularly when it comes to the burden of representation that disproportionately falls upon Black arts. In this dialectic “audiences push back and forth in a conversation with artists and institutions to combat the burden of representation while also addressing our heightened expectations.”[3] The “critical Black audience,” to use Irwin and Joseph’s phrase, is implicit in column one, and explicit in column two. Here we interrogate the ways in which critical Black audiences illuminate both the paradoxes and dialectics of Black representation in our “dual pandemics” era by resisting the ways in which Digital Blackface is performed by “culture vultures” in a continued theft of Black creativity.

Critical Black audiences, such as the Black Twitter users whom Andre Brock (2020, 23) credits with creating “cultural commonplaces, digital affordances, and digital sociality to build out a culturally coherent digital practice,”[4] call out the appropriative overrepresentation of all things melanin in the areas of media and entertainment. The pandemic has birthed an explosion of digital TikTok videos where non-Black people borrow, or, depending on your point of view, steal, Black vernacular, dance, and the presumed ways of Black teens’ style. In the WIRED article, “Stolen Moments,” Parham (2020) discusses how, on the one hand, “TikTok is joy and creativity, is Generation Z, is the future of entertainment.” However, Parham notes, TikTok is also “the exploitation of Black Culture at its most refined and disturbing” in the evolution of digital Blackface. Critical Black audiences that have visited the entertainment platform will notice the trend where Black culture is being appropriated by what is colloquially called “culture vultures”[5]; such appropriation often flattens and sanitizes Black cultural products so that they better fit in with white entertainers and their audiences.

One of the most glaring recent examples of culture vulture via TikTok is the popularized dance routine of the Renegade. This dance was created by fourteen-year old African American hip-hop/ballet/lyrical/jazz/tumbling/tap dancer Jalaiah Harmon, but stolen by white social media persona Charli D’Amelio. D’Amelio gained almost instant fame for her parroting of the dance. Harmon is perhaps an outlier case as she eventually received her credit for the dance, by, for example, performing it at the NBA All-Star Game in 2020. There are many Black creators who will never get their due. Indeed, some creators argue that white TikTokers have gotten better at crediting Black creators for their trends simply because Black creators and their followers have held them to account. Nevertheless, Black creatives fail to receive full credit for being the “backbone of language, humor, and trends” throughout social media.[6]

Just last month, in March of 2021, the Tonight Show with Jimmy Fallon helped catapult yet another white face, social media persona Addison Rae, while in the process erasing Black creatives on Tik Tok. Fallon featured Rae on his show teaching him (Black-created) Tik Tok dances without crediting the original Black creators, or having a Black dancer illustrate the dances. Fallon’s actions – featuring perhaps his own careless anti-Black racism or that of his network – were timed at a moment in which the platform TikTok itself was trying to address its own biases. Just a few weeks prior Tik Tok made an announcement of support for Black creators through the new incubator program designed to promote and foster Black talent. Jimmy Fallon has been in the hot-seat of racial controversy in the past due to his performance in Blackface, a moment for which he recently provided a twenty-year-overdue apology.

Fallon’s apology for performing in Blackface, followed not too long after by his show’s featuring of a “culture vulture,” is evidence that a more socially-acceptable form of anti-Black racism (appropriation and failure to credit Black creatives) is still tolerated as a form of entertainment. Although Blackface is often thought of as Blackface minstrel shows of the past, a new digitized emergence of white culture vultures, alongside images, GIFs, and cosmetic-darkened personae, is the contemporary iteration. This phenomena was coined “digital Blackface” by Joshua Lumpkin Green in his 2006 master’s thesis, “Digital Blackface: The Repackaging of the Black masculine Image.”[7]

But what IS digital Blackface? Simply put, digital Blackface is a type of minstrelsy for the internet age that comes in many forms. Black cultural studies scholar Lauren Michele Jackson, who further popularized the term “digital Blackface,” describes the performance in Teen Vogue as:

“[Images that] include displays of emotion stereotyped as excessive: so happy, so sassy, so ghetto, so loud…Rarely are Black characters afforded subtle traits or feelings. Ultimately, Black people and Black images are thus relied upon to perform a huge amount of emotional labor online on behalf of non-Black users.”[8]

The “excess” named by Jackson results in an overwhelming number of the memes, GIFS, and images featuring Black people reinforcing various stereotypes. In fact, the GIF hosting site, Giphy, provides users with searchable suggestions for their stereotypes by including terms such as, “Sassy Black Lady” and “Angry Black Man.” Stereotypes are thus built into the very logic of digital Blackface. Safiya Noble (2018) discusses the ways in which similar images have also been made into controversial filters on social media sites like Snapchat, where users can metamorphosize themselves and others to resemble Black individuals and further perpetuate the idea that Blackness is to be caricatured and seen as one of entertainment.[9]

Jackson’s naming of “emotional labor” also pertains to the ways in which critical Black users engage online with everyday white racism. These images – loved by white culture vultures and a number of white corporations (we see you IHOP) – have invaded our social media spaces through digitally exporting of Black bodies, art, and culture into mass culture; all the while, digital Blackface preserves the legacies of racism while somehow remaining beyond reproach.

Digital Blackface is a rebranding of the past through contemporary text-based appropriation of Black vernacular or image-based abuse of Black celebrities. This commodification of Blackness within the digital realm is one in which “race is technology,” to borrow Beth Coleman’s (2009) phrase, where the questions of “the biological and genetic systems that have historically dominated its definition [are removed and it is] denatured from its historical roots.”[10] Critical Black audiences know that minstrelsy thrives on platforms such as TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, YouTube, and the late 2016 Vine platform.

The “denaturing” of race through technology means that histories of racism are hyperpresent but seldom explicitly discussed. And because they aren’t explicitly discussed, neither is the history of Blackface minstrelsy. The earliest American iterations of Blackface emerged in the 1830s as a form of entertainment and was endured for more than a century. Sociocultural scholar Noël Duan (2017, 94) writes that Blackface today, especially in the fashion industry, illustrates how “white privilege is blind to and also blinds the acknowledgement of white supremacy in everyday society” when it comes to the responses of digital Blackface.[11] Appreciation and appropriation seem to be muddled through social media depictions, as white culture vultures perform but rarely appear to ponder what the stakes are when their ‘white’ bodies appropriate (sometimes, but not always, claiming to appreciate) the dances, or even the skin tone, ethnic features, and hair of perceived Blackness.

Another area of digital Blackface is Blackfishing, a derivation of the term “catfishing.” Blackfishing is slang for a non-Black person pretending to be Black online — Blackfishing refers to the growing practice of white media influencers using makeup, self tanner, and even plastic surgery to attempt to resemble a Black or mixed-race individual. This phenomenon could be the result of white creators realizing that there is an entire area of social media that is not centered on them. In response, white culture vultures alter their appearances by donning dining hoop earrings, lace front wigs that resemble Black hairstyles, and darker foundation or self-tanner. Critical Black audiences push back daily against culture vultures in small and large ways. From media literacy groups to social media message boards to academics, to of course Black Twitter, critical Black audiences bring continued attention to the issues of culture vultures in digital Blackface. As communication scholars Sarah Jackson, Moya Bailey, and Brooke Foucault Wells document, a variety of minoritized people engaged in “hashtag activism” work online daily to “build networks of dissent.”[12]

Culture vultures also want to perform “hashtag activism” as Blackface minstrelsy online is not simply deployed for fashion; culture vultures want to be seen as woke too. A new particular form of performative activism meets appropriation has been generated under the guise of “keyboard warriors.” These inactivists are quick to performatively signify activism, by, for example, changing their social media profile pictures to plain black boxes with messages of support for the Black Lives Matter movement and issues plaguing the Black community during moments like “Blackout Tuesday” after George Floyd’s murder. Critical Black audiences call out the insincerity of moments inactivism as performative activism.

The implications of digital Blackface are financial as well as emotional. Culture vulture content creators appear to have realized that the quickest route to success on social media platforms is through theft of Black expression and Black culture. Currently the rise of videos on social media platforms have allowed the creators to embody Black culture and almost reduce it to a caricature. But critical Black audiences read such moments of digital Blackface caricature in a resistant fashion: Brionna Blackmon, a TikTok user, asserts, “my Blackness is not a show, it’s not something you can just turn on.”[13] Yet, despite such protests, the increase of digital Blackface has catapulted to every corner of social media.

Much like the ways in which a critical Black audience reads moments of digital Blackface as Blackface minstrelsy for our dual pandemic era, culture vultures and their supporters must examine the images they share as daily instantiations of anti-Black racism.

Image Credits:

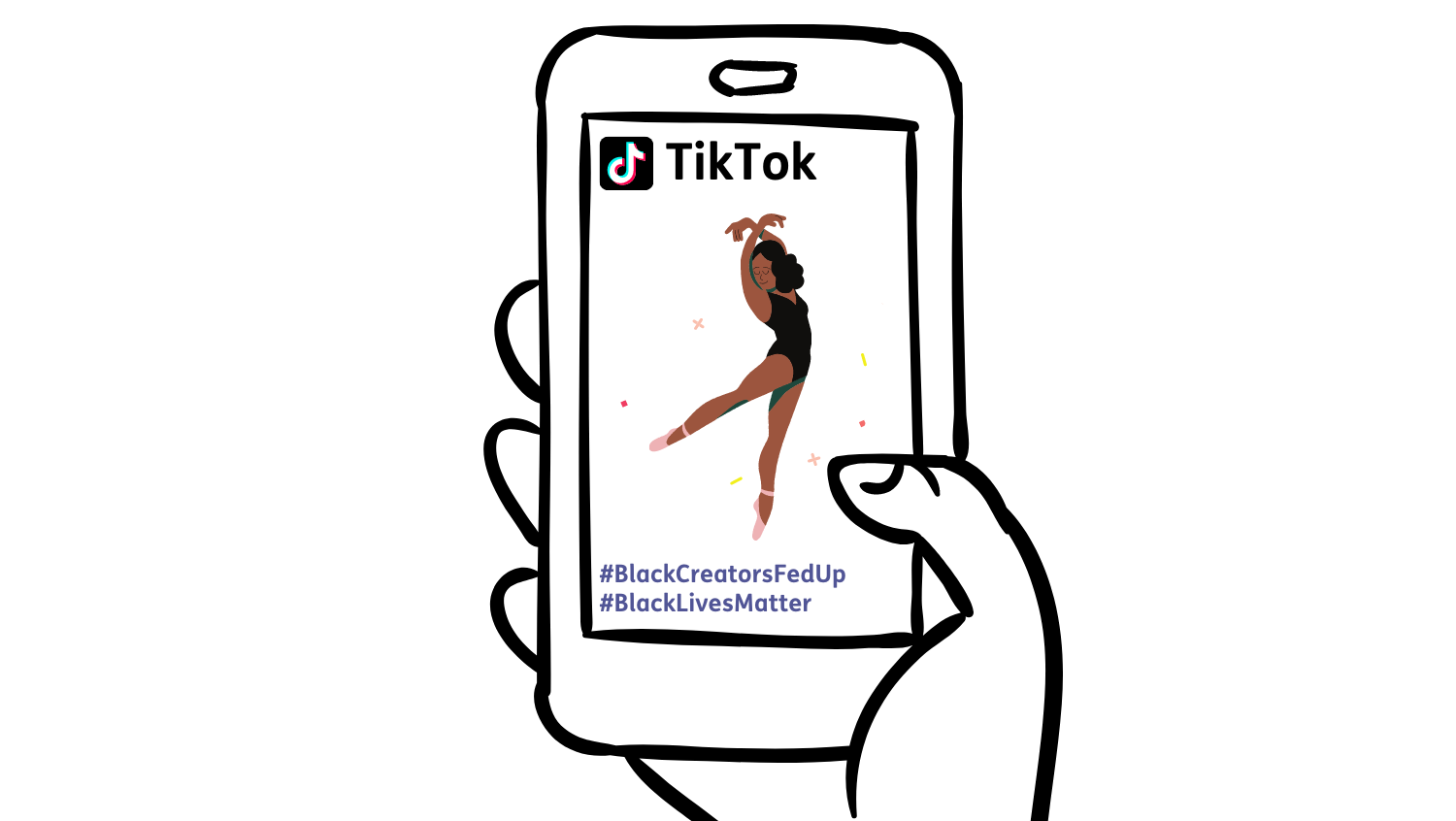

- Hashtags bring attention to Digital Blackface.

- Hashtags found on TikTok.

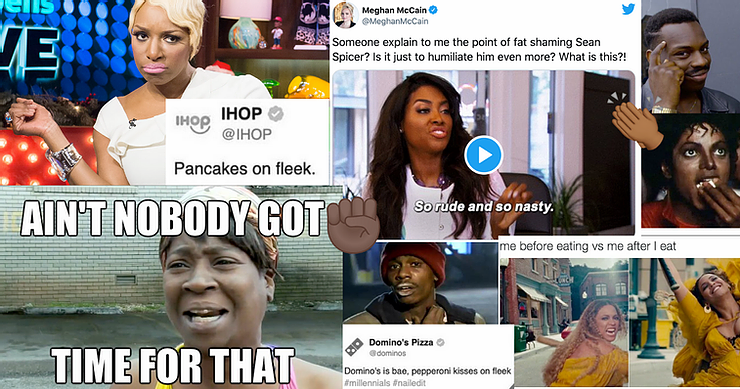

- Examples of Digital Blackface memes.

- Blackface in 1900 vs Blackfishing in 2020.

- Digital Blackface Meets Performative Activism. (authors’ screen grab)

- Cooper, J.N., Macaulay, C., and Rodriguez, S.H. (2019). Race and Resistance: A Typology of African American Sport Activism. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 54(2), 151–181. [↩]

- Hoskin, M.N. (2020, June 10). Performative Activism is the New ‘Color-blind’ Band-aid for White Fragility. Zora. Retrieved from https://zora.medium.com/performative-activism-is-the-new-color-blind-band-aid-for-white-fragility-358e2820a4e1. [↩]

- Irwin, L. and Joseph, R. (2021, February 3). Watching WOKE: An Exercise in Restraining Our Burden of Representation. Flow Journal. Retrieved from https://www.flowjournal.org/2021/02/watching-woke/. [↩]

- Brock, A. (2020). Distributed Blackness: African American Cybercultures. NYU Press. [↩]

- Parham, J. (2020, September). Stolen Moments. WIRED, 32–43. [↩]

- Rosenblatt, K. (2021, February 9). Months after TikTok Apologized to Black Creators, Many Say Little has Changed. NBCNews. Retrieved from https://www.nbcnews.com/pop-culture/pop-culture-news/months-after-tiktok-apologized-black-creators-many-say-little-has-n1256726. [↩]

- Green, J. (2006). Digital Blackface: The Repackaging of the Black Masculine Image. (Electronic Thesis or Dissertation). [↩]

- Hotlon, A. (2020, December 7). Digital Blackface: What It Is, Why It’s a Problem, and How to Avoid It. ACM Strategies. Retrieved from https://www.acmstrategies.com/post/digital-blackface-what-it-is-why-it-s-problematic-and-how-to-avoid-it. [↩]

- Noble, S. (2018). Algorithms of Oppression. NYU Press. [↩]

- Coleman, B. (2009). Race as Technology. Camera Obscura, 24(1), 177–207. [↩]

- Duan, N. (2017). Black Women’s Bodies and Blackface In Fashion Magazines. Critical Studies in Fashion and Beauty, 8(1), 65–98. [↩]

- Jackson, S., Bailey, M., and Focault, B. (2020). #HashtagActivism: Networks of Race and Gender Justice. MIT Press. DOI https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/10858.001.0001. [↩]

- Parham, J. (2020, September). Stolen Moments. WIRED, 32-43. [↩]

I’m so excited to see this topic being discussed. It is important that although Digital Blackface is being spread on social media, people should be aware of the negative aspects of this “trend”.

It is so refreshing to see a 2021 perspective of what someone of my age of 65 had to live through from TV shows to commercials and it makes me so proud

I am a white male that grew up in the midwest. This is a awesome to have it written this way. This is and has been way past due. This shows how much people look at race and not the heart. This is very educational and an eye opener for many. thank you, for writing this awesome report.

This topic is so relevant right now! I hope this reaches audiences that need to see the problems behind these videos and images.

Hot Damn! I can’t wait to share this.

Decided to wait and read this article when I had the time and I wish I had read it sooner. I’m anxious to see if this topic will be talked about in the areas of the beauty industry and how natural black hair is seen as “unprofessional”. Thanks for the great read.

This is awsome and refreshing at the same time this something the world needs to see and understand a clear pic at what this world vibes on great stuff cant wait for the movie….

This is an amazing and informative article that covers so much ground. I did not realize that digital Blackface is a term that is so succinct in its understanding, but captures the variety of racism found throughout mainstream and social media.

It always amazes me when I see a topic like this come across my newsfeed. This is what should be taught to our children, so they can learn from the repeated offenses in history. Kudos to the authors.

Pingback: Annie Agar – 3/3/24 – TikTok and the Evolution of Digital Blackface – Comm 3328-1 Media, Culture, and Technology