Substack Will Not Save Us

Austin Morris / University of Wisconsin, Madison

The rise of Substack is arguably the story of the year in the digital content industries, given the volume of writing done about Substack at year’s end.[1] Launched in 2017 by a combination of tech entrepreneurs and ex-journalists, the platform enables users to publish their work to the web and be sent directly to subscribers. Writers can set various subscription tiers, including paid subscriptions, that are managed by Substack, though the platform allows prospective subscribers to preview the content of the newsletter. Substack takes a 10% commission on those subscriptions.

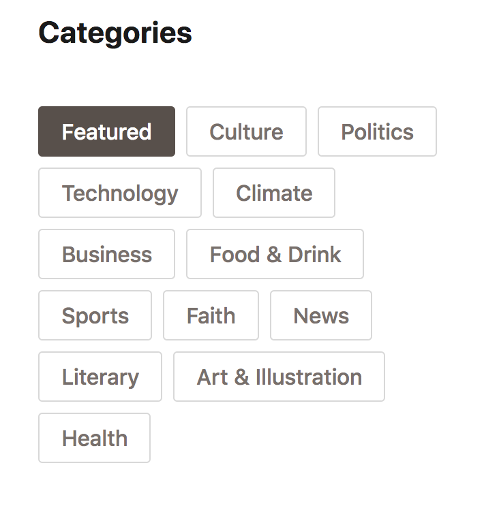

2020 saw an exodus of high-profile writers and journalists from their previous publications to Substack: food writer Alison Roman began “A Newsletter” following her extended leave from The New York Times; Hunter Harris left Vox Media-owned New York Magazine’s pop culture blog, Vulture, to start a Substack called “Hung Up”; Matt Yglesias, co-founder of Vox Media, left the company to start a Substack called “Slow Boring”; tech industry reporter Casey Newton left Vox Media brand The Verge to start a Substack called “Platformer”; Glenn Greenwald made an acrimonious departure from The Intercept to start a self-titled Substack. Some writers have been lured to the platform through substantial up-front advances (Yglesias, among others, have this arrangement), while Casey Newton publicly announced that he negotiated for a monthly healthcare stipend in lieu of an advance.[2] However, the vast majority of writers on the platform work outside of this system. Though Substack does limited editorial promotion to showcase work on the platform through its own blog or the “Featured” leaderboard on its homepage. That said, discovery must generally happen off-platform; you likely need to know the author or title of their newsletter that you’re searching for in order to find them, and you’re more likely to get there via social network links or a search engine than you are within the platform. Thus, a writer’s extant reputation within their industry, or their influence within particular social networks or online communities, may have an outsized impact on the potential value of their newsletter.

Presumably for branding reasons, Substack co-founders Chris Best and Hamish McKenzie seem interested in positioning Substack within the continuity of journalism’s industrial history, comparing his platform to the penny presses, which emerged in the U.S. in the 1830s and made advertiser-subsidized information more accessible to a greater share of the public.[3] Critic Michael J. Socolow, writing for NiemanLab, argues that the model more accurately mirrors the elite subscriber media that existed before the penny papers, given their lack of reach relative to free-to-read, ad supported digital media.[4] Substack claims that “more than 100,000 paying subscribers” constitute “early signs that we are witnessing the emergence of a new media economy,” with “top writers…making hundreds of thousands of dollars a year, and there’s a rapidly growing middle class, with writers and podcasters netting incomes that range from pocket money to high five figures.”[5] If you squint at this claim, though, it appears that a very small contingent of consumers are spending a large amount of money to support a contingent of Substack writers.[6] Still, Socolow asserts that Substack’s insistence that information and commentary should have a direct cost to its consumers is an important corrective to the advertising-driven digital media economy.[7]

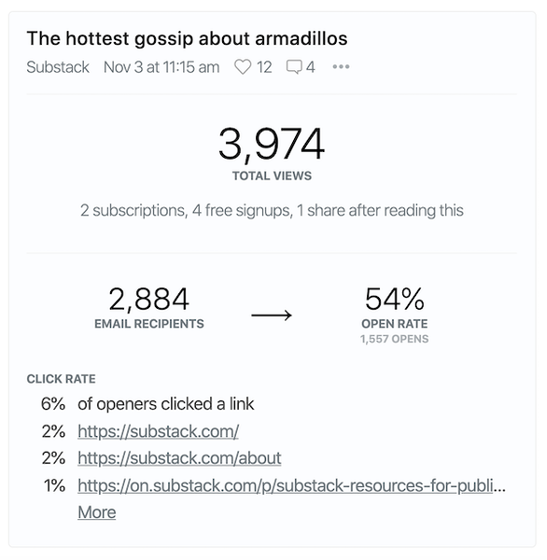

Generally, political economists critique U.S. media systems for their reliance on advertising and attendant commercial motives, which are understood to be in tension with public values.[8] These are systemic critiques, but they can also be observed in the affordances which shape the use of various platforms. For example, Substack joins many other user-generated content platforms in providing feedback to their writers in the form of metrics—a set of statistics about reader engagement with their work presented to writers. Substack also provides commentary on these metrics for their writers, giving guidance in how to interpret these metrics and how to use them to build out their business; they explain how to calculate a newsletter’s overall reach, what good engagement with individual posts looks like, and how to convert readers to paid subscribers. Despite distancing themselves from other platforms on the basis of their stance on positive content moderation–that is, accelerating the growth of viral content through algorithmic or editorial promotion, a feature that both Twitter and Facebook have implemented in different forms[9]–Substack’s instructions for considering and doing things with your metrics share key similarities to those of other user-generated content platforms, like YouTube. They are also not dissimilar from the editorial pressures facing current subscription or hybrid-subscription publications,[10] and so professional writers moving to Substack are likely familiar with these metrics and their common-sense interpretations. Newer writers, whose work Substack is publicly committed to fostering, may ultimately discover they need to do promotional work on other platforms to grow their readership and make those all-important conversions to paid subscriptions. In these ways, Substack should be understood primarily in the context of the user-generated content economy on the digital web, where social network site integration, scale thinking, and neoliberal self-branding discourses operate as relatively unquestioned industrial norms.

Substack touts itself as empowering for writers and readers, and that claim deserves to be taken seriously. Writing in The New Yorker, Anna Wiener observes that while Substack touts itself as a new home for journalism, original reported features are in the minority of what is published on the platform; instead, “the majority offer personal writing, opinion pieces, research, and analysis.”[11] For writers frustrated with low fees for freelance labor in an industry frequently threatened by layoffs, the opportunity to write for a specific audience and develop a sustainable income outside of that structure are important. But it also undeniably places the weight of success on individual writers and indicates an individualistic future for the success of digital media content. There is an entire established field of scholarly literature devoted to critiquing this neoliberal framework.[12] It is not difficult to see how sorting work published on the platform into leaderboards divided by genre while offloading the responsibility to build readership and convert readership into subscribers onto writers, Substack recreates the harmful platform dynamics that have devalued the work done and content produced by women, queers, and non-white people on other platforms. As someone who sees the struggle to build a new version of an industry that sustains a model of good, equitable working conditions as the key problem to be solved in the digital content industries, I remain skeptical that Substack is doing something substantially new that will revise or alter these inequities.

I follow the work of quite a few queer people in digital media; it did not surprise me when several of them started Substacks. Among them are “¡Hola Papi!” advice columnist and freelance writer JP Brammer, and ex-Teen Vogue, Out, and them. magazine editor Philip Picardi. Brammer’s advice column has shifted between at least three different online homes before he turned it into a free Substack. He and I both miss the “horny” illustration done to accompany the column while it was published by Out, but regardless, “¡Hola Papi!” remains one of the most affirming things to read online in any given week. Meanwhile, in the latest edition of “Fruity,” Philip Picardi’s newsletter, he lauds the successful collaboration between Rihanna and artist Lorna Simpson for the cover of the latest issue of Essence magazine, couched in dismay over Essence’s decision to furlough their entire staff on a week’s pay in September 2020. Of Essence’s troubles, Picardi writes:

One of the biggest problems plaguing Essence (which also plagues Out, The Advocate, and plenty of other “niche” media brands created by and/or for marginalized people) is that advertisers pay these magazines dust. When you work at a “niche” publication, you spend half your time as an editor (or a marketer! Or an ad salesperson!) explaining your audience to detached (and/or racist, homophobic, misogynistic) advertisers who write their financial commitments one full year in advance, always giving the same money to the same publications.[13]

Substack frames itself as a disruption of the political economics of digital media generally and journalism specifically, but it merely removes itself from one set of systemic issues and creates an environment where it is an individual’s responsibility to contend with the various problems faced by marginalized people creating content for marginalized people; advertiser influence is but one expression of more fundamental social problems that new platforms cannot solve. Substack is a stopgap measure which will inevitably, perhaps predictably, be more lucrative for some writers than others. Individual responsibility cannot be blamed for a lack of broad and substantial investment in politically leftist and majority-minority media content while right-wing media spinoff Substacks themselves generate investments comparable to those in Substack itself.[14] Substack’s investment in a set of up-and-coming writers on the platform through its Fellowship program is notable, but makes a change in the material conditions of freelance work only for its ten beneficiaries, and broader systemic change to the value and values of digital content production, distribution, and consumption remains critical.

Image Credits:

- Mehmi / Tenor GIFs

- Eloise Bridgerton reads the scandalous newsletter from “Lady Whistledown” in Netflix’s Bridgerton [2020] (Liam Daniel for Netflix).

- An example of the metrics page available to Substack writers, from a fictional Substack.

- Substack from their homepage: a list of the categories of Leaderboards; only the “Featured” page is explicitly curated by the platform, while others are the most-subscribed newsletters in their category.

- In addition to those cited or linked here, you might also read pieces on Substack from NPR or Columbia Journalism Review. Media industry reporter Peter Kafka called Substack one of the two biggest stories of the year in digital media, alongside continued consolidation of ownership, in a November interview with BuzzFeed and HuffPost Media CEO Jonah Peretti. [↩]

- Anna Wiener (2020) “Is Substack The Media Future We Want?” The New Yorker. Condé Nast. Dec. 28, 2020. Last accessed Jan. 15, 2021. [↩]

- Chris Best and Hamish McKenzie (2017) “A Better Future for News: Why We’re Building Substack.” Substack Blog. Substack. Jul. 17, 2017. Last accessed Jan. 15, 2020. https://blog.substack.com/p/a-better-future-for-news [↩]

- Michael J. Socolow (2020) “Substack Isn’t a New Model for Journalism — It’s a Very Old One.” NiemanLab. Nieman Foundation. Dec. 7, 2020. Accessed Jan. 15, 2021. https://www.niemanlab.org/2020/12/substack-isnt-a-new-model-for-journalism-its-a-very-old-one/ [↩]

- Hamish McKenzie (2020) “What’s Next for Journalists?” Substack Blog. Substack. May 18, 2020. Accessed Jan. 15, 2021. https://blog.substack.com/p/whats-next-for-journalists [↩]

- Clio Chang, writing for Columbia Journalism Review, suggests that the number of paying subscribers on the platform is now north of 250,000. Even at this number, and with the growth this suggests between May and December of last year, I think this point stands. [↩]

- Socolow (2020) [↩]

- See, for instance, Robert McChesney (2014) Digital Disconnect: How Capitalism Is Turning The Internet Against Democracy. New York: The New Press. [↩]

- Chris Best, Hamish McKenzie, and Jairaj Sethi (2020) “Substack’s view of content moderation.” Substack Blog. Substack. Dec. 22, 2020. Last accessed Jan. 15, 2020. https://blog.substack.com/p/substacks-view-of-content-moderation [↩]

- See, for instance, Angélé Christian (2020) Metrics at Work: Journalism and the Contested Meaning of Algorithms. Princeton UP: Princeton, NJ. [↩]

- Anna Wiener (2020) [↩]

- For instance: Brooke Erin Duffy (2017) (Not) Getting Paid To Do What You Love: Gender, Social Media, and Aspirational Work. New Haven, CT: Yale UP; Gina Neff (2012) Venture Labor: Work and the Burden of Risk in Innovative Industries. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [↩]

- Philip Picardi (2021) “How I Ended Up Crying on the Sofa Watching Gilmore Girls.” Fruity. Substack. Jan. 18, 2021. Last accessed Jan. 18, 2021. https://fruity.substack.com/p/how-i-ended-up-crying-on-the-sofa [↩]

- “The Dispatch,” a Substack from former editors of The National Review and The Daily Caller, recently received a $6 million round of investment. Substack’s first round of investment garnered $19 million from private equity firm Andreesen Horowitz, notable investors in Lyft and other gig economy companies (Wiener 2020). [↩]