Sitcom in the Trump Era: Racially Diverse Utopias and White Dystopias

Jorie Lagerwey / University College Dublin

Taylor Nygaard / University of Denver

This essay is the third and final column for Flow mapping particular aspects of a cycle of “quality” TV comedies we call Horrible White People shows that we argue work to televisually foreground a supposedly precarious, threatened, middle-class whiteness similar to other Trump era media products, despite their often-explicit self-critical liberal framing. Our previous columns addressed mental illness and insulated female friendships as representational trends that contribute to a racial dynamic that centralizes white precarity or white fragility in these comedies. In this column we highlight the ways that sitcom — a genre fixated on representing each era’s idealized norms of family, gender roles, and domestic spaces — shifts and evolves in the aesthetics of Horrible White People shows to reflect in the very structures of the genre the white fragility represented in characters’ actions and the shows’ tones throughout the cycle.

We’re focusing on sitcoms because of the genre’s traditional focus on stable, happy (typically white) families that are reconstituted at the end of every episode. Sitcoms have historically done the ideological work of creating and sustaining the ideal structure of the American family. Horrible White People shows, in contrast, are centrally concerned with the loss of access experienced by middle- and upper-middle-class white people to the trappings of the American Dream as laid out, among other places, in classic sitcoms from the 1950s and beyond: suburban home ownership, a stable well-paying job, and lasting, secure family relationships. This cycle of programming disrupts the aesthetic and ideological conventions of the genre, creating a dark dystopian picture of hetero relationships and threatening the stable, brightly lit comfort of sitcom’s domestic spaces. These shows have bled the sitcom into darkness, seriality, melodrama, and even musical (Crazy Ex-Girlfriend) to the extent that their primary identifying characteristics seem to be their focus on family and snarky wit rather than any stylistic, thematic, or even character consistency with the classic sitcom.

The darker lighting, isolating single camera cinematography, and grimmer aesthetics of cynical white family sitcoms underscore their dystopian fantasies of failed domesticity, thus centralizing families (whether nuclear or chosen) that are unable to protect members from the outside world. When Rebecca Bunch (Rachel Bloom), the titular Crazy Ex-Girlfriend is left at the altar, for example, she nearly harms herself, pushes her entire friend family away in a cruel diatribe, and relapses into serious mental illness; her emotional state is underscored by her fleeing her apartment’s domestic comfort for a bland hostel and the blue low-key lighting that frames her as she walks away (Figure 1, top). This colder aesthetic also structures the season three finale of You’re the Worst when Jimmy (Chris Geere) abandons his girlfriend (Aya Cash) immediately after proposing marriage on top of a cliff overlooking LA at night. The dystopian last shot symbolically depicts them both in a split screen composition of individual isolated medium close-ups (Figure 2, bottom) and the entire subsequent season chronicles Gretchen’s embrace of drugs, alcohol and inappropriate sex as she, now homeless, sleeps on the couch of her friend’s tiny studio apartment, while Jimmy lives incommunicado in an upstate trailer park for several months. Yet, at the same time as HWP shows have emerged, we’ve seen a parallel cycle of more conventional utopian sitcoms starring families of color — Black-ish, Fresh Off the Boat, and One Day at a Time — that illustrate immigrant and black families as succeeding in a neoliberal framework and insulating themselves from racial prejudice via a happy family togetherness.

The bifurcation of TV comedy in the 2010s into white-cast dystopias and people of color-cast utopias creates two very different sets of norms or expectations for the meaning of home and family — one safe and secure, one grim and threatened. This is a bifurcation of genre as well, where the utopian diverse cast programs adhere much more closely to static traditional modes of sitcom, while Horrible White People comedies consistently challenge the aesthetic and structural borders of the genre. This division in genre and representation is undeniably a racialized a division. And a racialized division that renders families of color resilient and forgiving in the face of racism and white people (most often not inhabiting traditional families) sad, confused, and vulnerable. This division is key to understanding the ideological field of the entire televisual landscape contributing to the centralization of white precarity in the Trump era.

Season 4 of You’re the Worst repeatedly enacts explicit and extreme critiques of the family of origin. In one remarkable episode (S4E3), the show breaks its own ensemble format and focuses on Gretchen’s travel home for the birth of her niece. The episode begins with Gretchen stopping by her suburban family home alone. Upon entering the house, Gretchen is framed from an overhead angle, purposefully disorienting the typical establishing shot of the sitcom’s communal spaces and ultimately abstracting Gretchen from the domestic environment — a feeling underscored by Gretchen’s actions, as upon entering she quickly puts on the hood of her sweatshirt and pulls the strings tightly around her face as if protecting herself from the space around her. Retreating from the home’s communal domestic spaces, she heads to her old room, now converted to a shabby-chic guest room, perfectly staged with crossed-stitched pillows and framed signs with the Wi-Fi password. Yet, Gretchen never turns the lights on and the cold low-key lighting makes the space feel eerie and inhospitable (Figure 3).

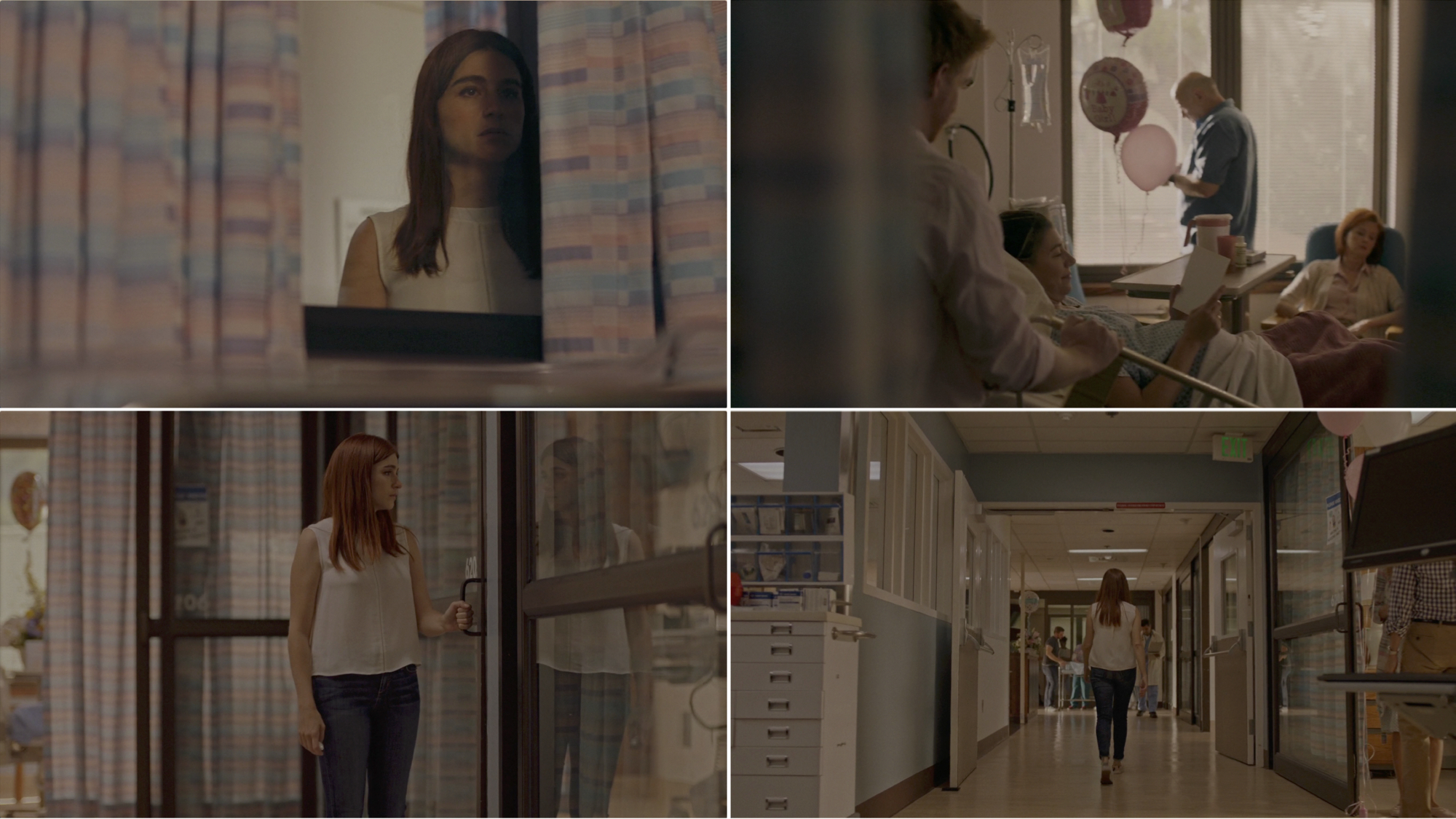

Throughout the episode, Gretchen avoids the hospital and her family, instead tracking down an old friend from high school, a digression that ultimately leads nowhere and provides no liberating understanding or character growth. The episode, instead, ends with a teary, even more disillusioned Gretchen hiding behind a curtain, her face cast half in shadow, looking into the brightly lit hospital room where her parents, brother and sister-in-law are gathered with the new baby. Gretchen makes eye contact and smiles at the baby but doesn’t enter the room or speak to anyone else; no one knows she was ever there and she simply walks away, in a move that represents her explicit rejection of or at least incapacity at fitting into this romanticized cliché image of nuclear family togetherness (Figure 4).

Illustrating similar cynicism about family, Casual and Transparent both euthanize ill fathers or father figures, killing mostly absent patriarchs in a rather overt metaphor for killing off, if not patriarchy, then an older social order that has become nonfunctional and burdensome. Yet in neither show does this serve as catharsis or offer a suggestion for any new order. Instead, the narrative simply continues, and characters return to their narcissism and ennui. So, while they lack the repetitive episodic structure of traditional sitcoms, the serialized storylines, and other vignette or sketch structures of HWP shows never enable character development. The ideological dissolution of the self-sufficient neoliberal nuclear family common in this cycle isn’t replaced with anything. The contemporary visibility of anti-racist protest and emerging feminisms — for these affluent, liberal white characters — leads almost inevitably to sadness or even relapse into mental illness (as discussed in our first column): a nostalgic yearning for a family past that turns out to be misremembered or no longer available.

In stark contrast to the rejection of the heterosexual nuclear family on so many Horrible White People shows, there is a small surge of half hour TV comedies that could be fairly characterized as their exact opposite. Mass market sitcoms with non-white families are the generically conservative counterpoint to Horrible White People shows’ genre experimentation. If HWP shows’ generic experimentation signals a disruption in the genre’s classic representation of the heterosexual nuclear family, these shows’ adherence to generic norms and traditions result in an embrace of the nuclear family as the site of all problems’ solutions.

Their very traditional sitcom aesthetics help construct them as utopian families. They use multi-camera set-ups (albeit somewhat updated and more flexible than older shows in the genre) and utilize the very bright uniform lighting associated with that shooting style. All three shows rely on an abundance of shot/reverse shot conversations to set up jokes and move the plot forward. And they have almost entirely contained episodic structures (there is some serialization, but you’d be able to jump in and understand any episode in any order). One Day at a Time still relies on a laugh track, and other shows, like Black-ish, use musical cues to the same effect. These shows have limited sets with a heavy emphasis on the domestic space, especially kitchens and living rooms. Even the color palettes are bright and cheery. Importantly though, despite some clear aesthetic similarities, these diverse cast sitcoms don’t necessarily fall into the same critiques lodged at The Cosby Show for the logic of colorblindness. [1] On the contrary, these shows illustrate a certain amount of cultural specificity or even acknowledgement of racism and structural inequality. But in return, so to speak, the programs adhere to traditional sitcom aesthetics and narrative structures, often resetting their happy family premise at the end of every episode, erasing any conflict with white neighbors or coworkers by showing the whole family happily together in their home at the end of an episode and beginning the following episode as if the racial tension or conflict left no residual effects.

In One Day at a Time’s second season opener “The Turn” (S2E1), for example, the usually well-mannered Cuban American teenage son, Alex (Marcel Ruiz), gets suspended from school for punching a kid who told him to “Go back to Mexico.” The focus of the episode is a family discussion on the living room’s couch, interrogating the personal and social impact of racial slurs and stereotyping — one that takes into account intersectional differences in experiences of racism, including generation with the grandmother (Rita Moreno) and the privileges of racial passing from the daughter (Elena Alvarez). While the episode tackles a lot of the complexity of race relations in the U.S. and the lack of easy fixes, it nonetheless ends with the mom, Penelope (Justina Machado), reassuring her son of his worth and her unwavering support in him as the family comes together over ice cream, which in Penelope’s words is “the one thing that completely stops the effects of racism.”

Families of color are welcomed into this dominant generic space, then, because they carry the burden of maintaining this national ideal and repairing its historical association with whiteness. Robin James has argued that white supremacy is as inclusive as possible, right up until it becomes a bad deal for white people. Or until white people might have to relinquish some of their privilege to make room for others. [2] These sitcoms featuring families of color work in the same way: They have complexity, they have extended families, they even have a certain amount of critique of the racial order couched in comedy. But in exchange, so to speak, they support the neoliberal ideal of self-sufficient families.

There are strong parallels to be made between this recent proliferation of happy families of color and the brief abundance of black-cast sitcoms in the mid-1980s to early 1990s. As Herman Gray notes, the prevalence of black cast sitcoms coincided with a sharp decrease in broadcast network viewership. More diverse programming was a tactic of a TV industry in transition and under the strain of competition brought by new technologies. Gray writes of that earlier era, “The recognition and engagement with blackness were not for a moment driven by sudden cultural interest in black matters or some noble aesthetic goals on the part of executives in all phases of the industry. In large part they were driven, as most things are in network television, by economics.” [3].

In later work, Gray amended his argument to say the “periodic crisis in television over racial representation is less about the network’s loss of markets and audience shares than about governance and order.” [4] One does not preclude the other, however. We argue that global recession, changing TV technologies and modes of distribution, more visible racial violence and protest for racial, gender, and other types of civil rights form a specific historical conjuncture that creates both the utopian sitcoms with black, Latinx, and Asian-American families and their dystopian white-cast counterparts. The fact that this substantial cycle of sitcoms with similar aesthetic innovations and thematic concerns about dystopian white nuclear families all emerged within a few short years needs to be understood as part of a dominant cultural ethos during the Trump Era, reflecting and shaping the ideological tensions and anxieties of this cultural moment, especially that of white precarity.

Image Credits:

1. FXX Season 4 promotional image/ABC Season 1 Promotional Image

2. Top: Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, Season 3, Episode 4 (author’s screen grabs)/ Bottom: You’re the Worst, Season 3, Episode 13 (author’s screen grabs)

3. You’re the Worst, Season 4, Episode 3 (author’s screen grabs)

4. You’re the Worst, Season 4, Episode 3 (author’s screen grabs)

5. Promotional posters

6. Black-ish, Season 4, Episode 2 (author’s screen grabs); One Day at a Time, Season 1, Episode 13 (author’s screen grabs); Fresh Off the Boat, Season 1, Episode 1 (author’s screen grabs); Fresh Off the Boat, Season 3 promotional image

7. One Day at a Time, Season 2, Episode 1 “The Turn” (author’s screen grabs)

8. One Day at a Time, Season 2, Episode 1 “The Turn” (author’s screen grabs)

Please feel free to comment.

- Jhally, Sut and Justin Lewis. 1992. Enlightened Racism: The Cosby Show, Audiences, and the Myth of the American Dream. New York: Routledge. [↩]

- James, Robin. 2015. Resilience & Melancholy: Pop Music, Feminism, Neoliberalism. Alresford, Hants, UK: Zero Books. [↩]

- Gray, Herman. 1995. Watching Race: Television and the Struggle for ‘Blackness.’ Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 68. [↩]

- Gray, Herman. 2005. Cultural Moves: African Americans and the Politics of Representation. Berkeley: University of California Press, 89. [↩]