The PyeongChang Winter Olympics and Korea’s Musical Modernities

Patty Ahn / UC San Diego

This year’s Winter Olympic Games in PyeongChang, South Korea featured two strikingly different soundtracks. On one hand, the sounds of K-Pop flooded the mediascape as A-list idols performed nightly at the Olympic headliner show, took the stage for numerous promotional concerts held in lead-up to the Games, and closed out the entire Olympic event with show-stopping performances. During the opening ceremony, the industry’s most famous anthems played in the background as delegations from Chile, France, the U.S., and many others marched in the ritual “Parade of Nations.” The score was meant to offer a curation of South Korea’s most popular songs from past to present with K-Pop serving as the pinnacle of this sonic progression.

These celebratory sounds, however, were met with a more somber tune. As Trump’s escalating aggression toward the DPRK [1] led many to fear that a preemptive strike by the U.S. loomed on the horizon, leaders from North and South Korea announced that they would form a unified women’s ice hockey team and march as one delegation in the opening ceremony. In a historic and much anticipated moment, athletes from both countries entered the “Parade of Nations” together, waving white flags emblazoned with a solid blue silhouette of the peninsula while the melancholic melody of “Arirang,” Korea’s national folk song, wailed in the background. The message of this profoundly symbolic gesture was resoundingly clear: the DPRK and ROK were unified in their call for peace and shared dream of reunification.

The languid and pastoral notes of “Arirang,” which served as the unified team’s official anthem, could be heard across the Games, offering a striking counterpoint to K-Pop’s more futuristic reverberations. I bring attention to these two scores because of the very different feelings they inspire about Korea. In this post, I gesture toward some of the affective structures at work within these musical registers. The dichotomous feelings captured in K-Pop and “Arirang” in many ways speak to a fundamental crisis in South Korea’s identity as a nation and the global image it projects, but I believe an important story also lies in their dissonance.

K-Pop’s trademark melange of electronic dance beats, robotic vocals, neon-laden music videos, and razor sharp choreographies has served as the defining visual soundtrack for South Korea’s postmillennial reinvention. The unexpected success that Korean pop music and television dramas found in the Asian market in the late-1990s buoyed the country’s economic recovery in the wake of the IMF Crisis of 1997. Since then, it has played a central role in supporting the government’s agenda of remaking the country’s reputation as a global leader in cultural and technological innovation.

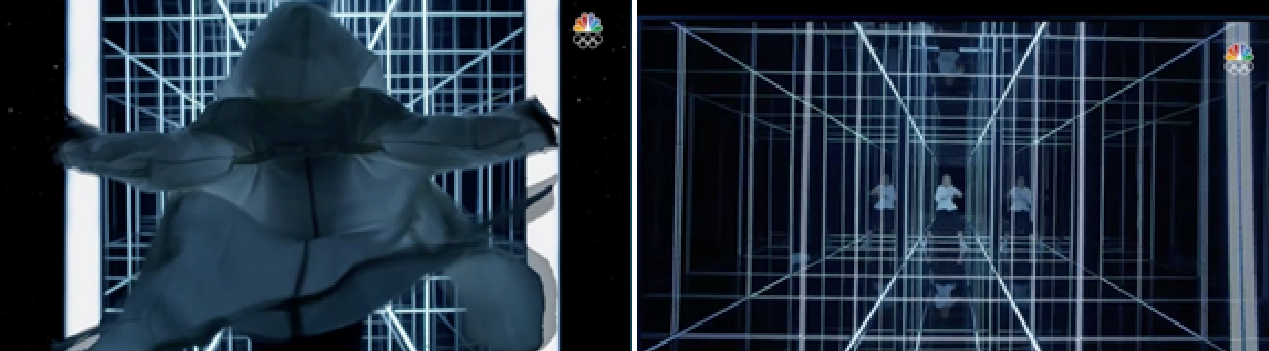

The opening ceremony at this year’s Olympics reinforced this technological narrative. The artistic segment of the program used a mix of live action performance and virtual reality animations to depict the journey of five children as they travel through Korea’s past, present, and eventual future. Their story begins in pre-modern Korea, where holograms of ancient cultural artifacts and mythologies come to life around them, and concludes at the “gates of the future” where they learn that their careers as K-Pop star, artificial intelligence specialist, urban simulation expert, hologram specialist, and doctor await them. They watch in wonder as a virtual screen appears before them playing a montage in which their future selves excitedly perform their jobs inside an illuminated grid.

International sporting events like the Olympics and World Cup have provided their host countries with a critical opportunity to re-make their image in the world. This year’s Winter Games in PyeongChang clearly sought to re-orient our imagination about South Korea as a hyper-technologized modernity soaring into its future and solidify the integral role that K-Pop has and will continue to play in shaping this narrative.

K-Pop has already begun to reshape South Korea’s place within the American imaginary in profound ways. Seoul and Busan have become Hollywood’s latest “techno-Orientalist” backdrop with visual motifs taken right out of a K-Pop music video.[2] Meanwhile, countless media stories dedicate themselves to unlocking the mystery behind Korean culture’s recent spate of success in the global market. At the same time, K-Pop has also performed the work of creating a historical amnesia around Korea as it pivots us toward a futurist vision of the country.

The U.S. by and large has lacked a historical framework for how to speak about Korea in spite of its commanding role in manufacturing and maintaining its division. Mainstream media rarely acknowledge North Korea’s existence, except through the occasional caricatured depiction of an erratic and hostile leader. Otherwise, the dominant story told about the U.S’s relationship to South Korea is of “an enduring and equal partnership in the face of a shared enemy,” [3] Yet, Washington has systematically thwarted numerous peace and reunification efforts in the peninsula. In addition to imposing devastating sanctions on North Korea—which have only resulted in humanitarian crises, the U.S. has backed three brutal anti-communist military dictatorships (1961-1992) and continues to maintain a military presence across the south.

Official state narratives about the Korean War (1950-present), known in the U.S. as “the Forgotten War,” has suppressed our historical memory about the nature of the U.S.’s involvement in Korea. The U.S. Cold War in Asia began in Korea, which it saw as key to maintaining a capitalist stronghold and military power in the region. However, the military campaign there, which resulted in the loss of more than 4 million Korean lives (70% of which were civilian), was perceived by and large as a failure. The signing of the Korean Armistice Agreement in 1953 installed a temporary cease-fire until a “peaceful settlement” between the north and south could be reached, but this accord has yet to be fulfilled, leaving intact a militarized border that continues to separate ten million families.

The sounds of “Arirang” at this year’s Winter Games haunted K-Pop’s technology-driven vision of Korea’s future with the ghosts of an unresolved past. The song has been sung across the peninsula for hundreds of years—long before Korea’s division into two rival nations—and has come to represent an idea and feeling of an ethnically unified Korean people. It became a rallying cry for independence under Japanese colonial rule (1910-1945). Commonly associated with a sense of sorrow, longing, and separation, it has come to serve as an expression of grief over Korea’s ongoing division and unfulfilled dream of liberation.

This year’s Olympic Games did not mark the first time the two countries appeared at an international sporting event as a unified delegation. However, it did seem to signal an important shift in mainstream American discourse about Korea. Although NBC commentators more or less universalized the message of peace at this year’s games, as Korean historian and peace activist Ramsay Liem notes, the two Korea’s unified departure from Trump’s military aggression began to destabilize the idea of the U.S. as “equal partner.”

Although we still face an uncertain future with respect to Korea, , we might continue to hold onto “Arirang” as a way of listening to these rare moments of dissonance in Korea’s soundtrack. Unlike K-Pops’s highly rationalized and vertically-integrated system of song production, “Arirang” has never been defined by a standardized set of lyrics or melodic structure. A song is called “Arirang” so long as it contains this passage, “Arirang, Arirang, Arariyo/ Arirang gogaero neomeoganda,” which simply translates as “Arirang, Arirang, Arariyo/ Crossing over Arirang pass.” More than 8,000 variations of the song exist with countless regional variations and thousands of known lyrics. Even the word “Arirang” itself possesses no stable meaning—it is simply an imagined place or feeling.

In many ways, “Arirang” is more than a song or even a feeling. It offers us a capacious and historically messy way of knowing–an entry point into those stories of Korea which might not conform to official narratives. “Arirang”‘s recall of the past pleaded for an alternative vision of Krea’s future–one oriented toward peaceful reunification, liberation, and sovereignty from foreign rule.

Image Credits:

Author’s screengrabs

Please feel free to comment!

- North Korea’s official name is the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). South Korea is officially titled the Republic of Korea (ROK). [↩]

- David S. Roh, Betsy Huang, and Greta A. Niu, Techno-Orientalism: Imagining Asia in Speculative Fiction, History, and Media (Rutgers University Press, n.d.).

[↩] - https://www.counterpunch.org/2018/02/09/south-korea-straying-off-the-leash/ [↩]

Pingback: The PyeongChang Winter Olympics and Korea’s Musical Modernities | Zoom in Korea