Algorithmic Advertising and the Perils of Personalisation

JP Kelly / Royal Holloway College, University of London

A recent and somewhat controversial example of how a promotion emphasises particular elements of a text. In this instance, Netflix’s Godless (2017) was initially marketed through posters and trailers as a female-oriented Western. However, as critics were quick to point out (as in the Tweet above), male characters enjoyed the lion’s share of dialogue in the pilot episode.

Since Netflix debuted their first original series in 2013, House of Cards, there has been a growing body of scholarship examining the implications of the company’s data-driven approach for the production, distribution, and consumption of film and television. Almost all of this work has focused on the content itself – on the programmes that have (supposedly) been commissioned through a combination of algorithms and human instinct. However, far less has been written about the SVOD giant’s promotional practices, which, as the images above indicate, are equally worthy of study even if they have somewhat gone under the radar.

This post examines Netflix’s algorithmic promotional practices, setting them in relation to a longer history of marketing in the entertainment industries. By doing so, I hope to draw out some of the key similarities and differences between analogue (for want of a better word) and algorithmic advertising, and to briefly consider some of the implications of these emerging practices for how we choose, interact with and experience content via services such as Netflix.

Thumbnails: The Art of Selection

Though Netflix has a relatively limited brand presence within traditional marketing spaces such as billboards, newspapers ads, TV commercials, etc. (in the UK at least) promotion is nevertheless at the heart of how the company operates. Indeed, we can think of the Netflix interface itself as one big promotional arena in which titles constantly vie for our attention, their arrangement and choice of artwork (thumbnails) determined by complex algorithms that rely on a vast and dynamic body of data. The process through which these promotional thumbnails are created, selected and positioned warrants critical attention not least because, as Ed Finn has recently argued, ‘the [Netflix] marketing and recommendation framework itself has become a new form of authorship’. [1]

According to Finn, this framework encourages the production of certain kinds of content (and thus constitutes a form of authorship). However, from a promotional point-of-view, the framework also encourages particular kinds of readings, specifically through the use of personalised thumbnails (more on this in a moment). As Jonathan Gray has argued, paratexts such as trailers and posters ‘play a constitutive role in establishing a “proper” interpretation for a text’. [2] Positioned as they are at the “threshold of interpretation” – to borrow Gérard Genette’s term [3] – ‘paratexts tell us what to expect, and in doing so, they shape the reading strategies that we will take with us “into” the text,’ and ‘provide the all-important early frames through which we will examine, react to, and evaluate textual consumption’. [4]

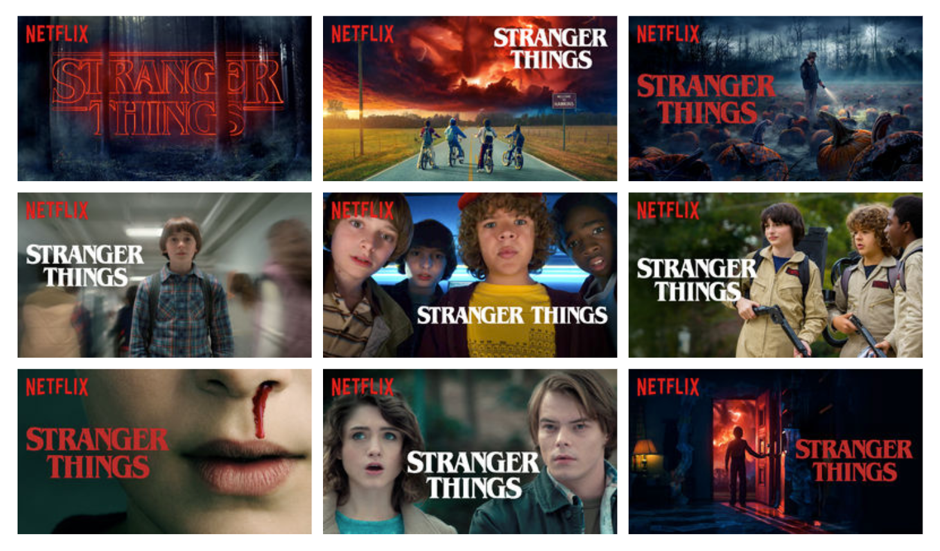

Whilst these definitions and functions of “analogue” promotional paratexts map neatly onto more conventional marketing practices, they are less effective at describing the algorithmic approach employed by Netflix. For one thing – and here is where algorithmic and analogue practices begin to diverge – there is often no single promotional thumbnail for a title. Instead, many series and films – particularly Netflix Originals – have multiple thumbnails which are selected and then displayed depending on a range of different (and largely invisible) factors. Take for example, Stranger Things, which according to a recent Netflix Tech Blog has at least nine different thumbnails.

Though many of these thumbnails reinforce genres that we might already associate with the series, such as sci-fi or horror (in particular, the top row and the bottom right image), others seem somewhat less representative of the programme. For example, the bottom-middle image (featuring Nancy and Jonathan) emphasises the relationship between these two characters, thus promoting the series through a very different generic lens (i.e. drama, teen romance), perhaps even encouraging viewers to foreground this plot over others. Other thumbnails, such as the one in which Mike, Dustin and Lucas are dressed in replica Ghostbuster’s costumes exaggerates the series more comedic elements, thereby appealing to viewers who may be less interested in sci-fi, horror, or even romance, and ultimately resulting in a different framing and a potentially different interpretation of the text.

The generic diversity of these thumbnails and the complex process through which they are selected, positioned and displayed, poses an interesting question: to what extent can these promotional paratexts still be considered to ‘play a constitutive role in establishing a “proper” interpretation for a text’ when they are clearly so diverse, highly-personalised and, at times, unpredictable? [5]

From Diverse Marketing to Hyper-Personalisation

Of course, a diversified marketing campaign that promotes different generic traits of a text in the hopes of attracting a broader audience is hardly a novel approach in the history of media entertainment. Take for example King Kong (1933), a film well-known for such a strategy. As Cynthia Erb explains: ‘its reception dynamic was a comparatively mobile, shifting one, in which distributors and exhibitors kept recalculating the terms of the campaign in an effort to re-present the film’s features in their best (and most profitable) light’. [6] This involved, amongst other things, pitching the film’s different genres – romance, action, “jungle movie”, etc. – to different kinds of audiences, often in different, gendered promotional spaces.

This approach has long been practiced within the entertainment industries and in principle is no different to the promotion of titles on Netflix, which similarly utilises a range of promotional imagery in order to appeal to different consumer interests and identities. At the same time, however, it constitutes a fundamentally different process, one that lacks the automated, instantaneous and highly-personalised characteristics of Netflix’s algorithmic model.

Though people often marvel at the efficacy of algorithms, some critics have expressed concern about their innate capacity for hyper-personalisation. As Gartner’s Martin Kihn has recently argued, algorithms (or “algos”) can be very effective at targeting consumers and tailoring campaigns, but they can also ‘build a commercial echo chamber and hone us down to our obvious features’. As he goes on to elaborate:

Every time an optimization is made, some data is discarded. Usually it’s data that doesn’t fit the model, which are exactly the features that make us unique. Our algo addiction is a hidden threat to advertising’s function as a catalyst of discovery. [7]

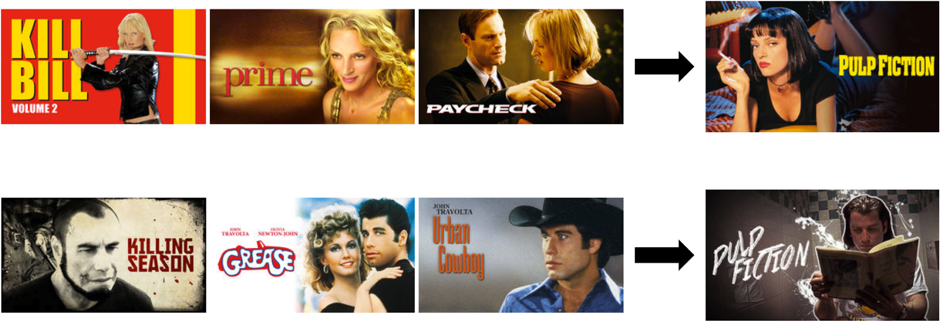

In the case of the Netflix interface, not only does this mean that we are perhaps more likely to be offered the same kinds of content that the algorithm thinks will appeal to us (thereby diminishing the possibility of serendipitous discoveries), but that the promotion of these titles is increasingly personalised in such a way as to appeal to and further reinforce our generic preferences. Moreover, as scholars such as Genette and Gray have demonstrated, paratexts such as these produce certain kinds of framings and interpretations of a text, as per the Stranger Things thumbnails above or the Pulp Fiction examples below.

To be fair to Netflix, the company has publicly acknowledged the limitations of algorithmic curation on more than one occasion via their Tech Blog, with several posts [1, 2] detailing the various measures they have taken in order to avoid creating the kind of algorithmic echo chamber as described by Kihn. Nevertheless, the development of highly-personalised, algorithmically driven promotional thumbnails does suggest that we are now at a new frontier of marketing, one that has profound implications not just for what the promotional machine allows us to discover (or not to discover), but also in terms of how it increasingly encourages us to view the same texts through very different and highly-personalised promotional lenses.

Image Credits:

1. Godless tweet

2. Godless Thumbnails (author’s screen grab)

3. Stranger Things Thumbnails

4. King Kong Promotion (author’s screen grab)

5. Pulp Fiction Thumbnails

6. House of Cards Thumbnails (author’s screen grab)

Please feel free to comment.

- Finn, Ed (2017) What Algorithms Want: Imagination in the Age of Computing. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. [↩]

- Gray, Jonathan (2010) Show Sold Separately: Promos, Spoilers and Other Media Paratexts. New York: NYU Press. [↩]

- Genette, Gérard (1997) Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [↩]

- ibid. 26. [↩]

- ibid. 49 [↩]

- Erb, Cynthia (1998) Tracking King Kong: A Hollywood Icon in World Culture. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press. [↩]

- Kihn, Martin (2017) ‘The Perils of Algorithmic Advertising’, Gartner, May 2nd. Available at: https://blogs.gartner.com/martin-kihn/the-perils-of-algorithmic-marketing-2/ [accessed Jan 12th, 2017] [↩]

“…[B]ut that the promotion of these titles is increasingly personalised in such a way as to appeal to and further reinforce our generic preferences.”

In response to this particular point in the article concerning Netflix boiling its viewers down to their most generic selves, I don’t believe the company would see this as a negative. Case in point, the changes made to their rating system in early 2017. Users previously had been able to rate titles from one star to five stars, and for shows or movies that hadn’t been rated, Netflix would guess what the user would grade a title based on their previous ratings. Now, a user can select thumbs up or thumbs down for a title as opposed to the five-star system, and Netflix will learn from that and predict the user’s percentage of interest for other titles.

In my personal experience, the rating system went from being highly effective, in regard to knowing how I would respond to a title, to providing extremely generic and/or inaccurate predictions. The thumbs up or down system is conducive to a mindset of ‘watch or don’t watch’ rather than one that is sensitive to nuances in personal taste and interest, and Netflix has to be aware of that. I do not believe they care how much I am enjoying a program, as long as I am watching something. And they want to sell viewers, more than anything, their original programming. This is easier to accomplish when they generalize recommendations and view people in their most generic form.

Pingback: IT’S NOT FATE, IT’S PROGRAMMATIC ADVERTISING. – THE WORLD OF DIGITAL MARKETING

Pingback: Digging Into The Unique Business Model of Netflix – Elizabeth Kinnison

Indeed its awesome movie, I have watched it recently

Thanks for sharing that.

Pingback: Coronacinema: TIFF 2020 in Reflection - Nouvelle News

Netflix earn more than any other network during this coronavirus season. Thats show how much strong their marketing policy is. Anyway thanks for the sharing.

I watched some movies recently, they are great.

The Badr vs. Benny fight was initially expected to take place at the Ahoy Arena in Rotterdam, Holland in June, serving as the headliner of

This is really great things

Thanks for the blog filled with so many information.