Of Bhakts, Deplorables and More: Posthuman Communities Performing Political Partisanship in the Age of Social Media

Sushant Kishore / BITS Pilani

The 2014 General elections in India and the 2016 Presidential elections in the USA shared a list of attributes, from two-terms of incumbent liberal governments to the rise of the extreme right to power. Both elections laid bare the complex virtual/real helix that constitutes the digital sensorium that is the contemporary world. Large numbers of netizens were called upon in both constituencies to join ranks with the candidates. In the case of India these groups appropriately called themselves, “Modi’s army”. Neither internet, nor politics has been the same since the 2014 elections. The internet emerged as a political tool where false truths, rumors, sentimentality and sensationalism could explode with a click and eclipse all opposition and politics became more internet marketing than polity. Campaign rhetoric and name-calling became hashtags and hashtags became social media communities.

Theoretically, at the intersection of the digital, the political and the performative, this column attempts to explore the changing terrains of politics with respect to the digital media and the performatives of communitas and political partisanship in the context of the 2014 General Election in India and the 2016 Presidential Election in the United States. The objects of interest are the posthuman social media communities that extensively participated, through multiple social media platforms, blogs, micro-blogs, etc., in the aforementioned election campaigns and continue to shower uncritical and absolute loyalty on the candidates for the highest administrative post in the two largest democracies of the world: India and United Sates of America.

The Digital-Political

Articulating, the mid-20th Century techno-human condition, Marshall McLuhan wrote –

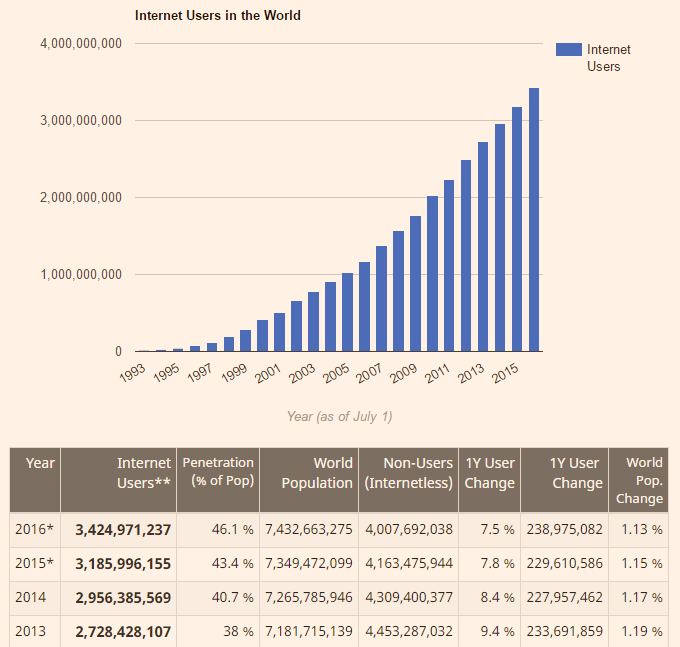

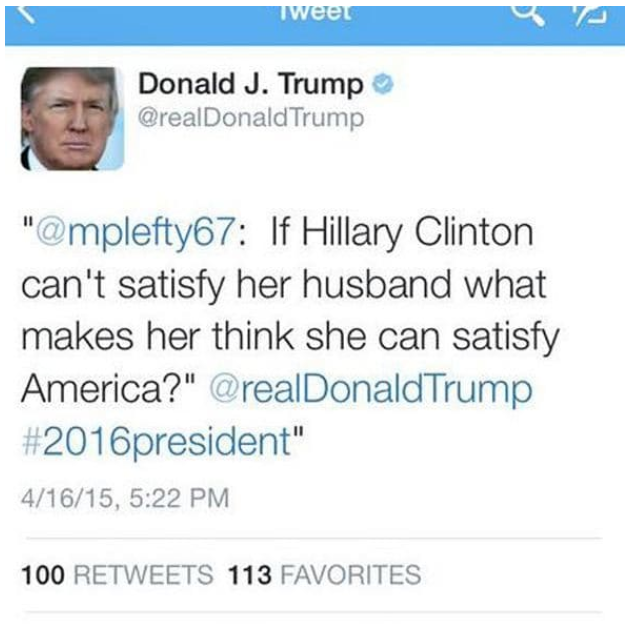

This was in the 1960s when the electronic medium had started gaining traction in the west, the television and radio had become common household furnishing. The computer had just reached its adolescence and internet was yet to be conceived. In the contingent milieu McLuhan foresaw what the future of technology had in store for humans. With the internet boom, the McLuhanian the digital sensorium expands to envelope all aspects of quotidian life. The internet is growing exponentially and covers over forty-six per cent of the world population. If technology was the extension of the central nervous system in 1960s, the internet embodies the prosthetization of consciousness itself (another Mcluhanian prophecy). A consciousness that is rhizomorphic – networked and hyperlinked with infinite others, virtual and built/stored on inconspicuous corporate servers yet personal and quantifiable with a cornucopia of information – facts, fictions, news, rumors, data, memory – easily retrievable through keyword searches. 2 These attributes that make the silicon consciousness remarkably seductive and widely accessible to all, also evoke an impression of democratic rapture where a user has the luxury of disembodied presence and disembodied unreasoned voice. Any individual can set up a blog or a website at minimal cost and with minimal skills and social media removes even these hurdles. Social media allows and encourages (with Twitter’s 140 words microblogs) instant, knee-jerk reactions to be posted to the world without any inhibition and/or fear of intellectual confrontation. The episode of the first presidential debate best illustrates what I mean by the “luxury of disembodied presence.” Donald Trump confessed he refrained from bringing up Bill-Lewinsky because he saw Chelsea Clinton in the audience but he could uninhibitedly do so, about Hillary and several other women, on Twitter.

Very often the social media does indeed give “legions of imbeciles the right to speak, when they once only spoke at a bar after a wine, without harming the community.”3 Within seconds the post snowballs with likes, comments, retweets, shares, reposts of like-minded individuals until the unreasoned impulsive argument/opinion starts to “#trend”. Manufacturing consent becomes easier in this digital prosthetization of the consciousness where users, through their Twitter feeds, Whatsapp, Facebook walls, and more, are constantly bombarded with information/misinformation and search engines literally froth with content manipulated with keywords, backlinks and shock-value. This is the picture – this constant wrestle of attention and distraction – that informs politics in the age of social media. Our ability to assess political candidates and make political decisions has become impetuous, conforming to the configurations of the digital milieu. “Once scuba diver[s]…. Now… [we] zip along the surface like a guy on a Jet Ski.”4

2014/2016 – Performing Political Partisanship

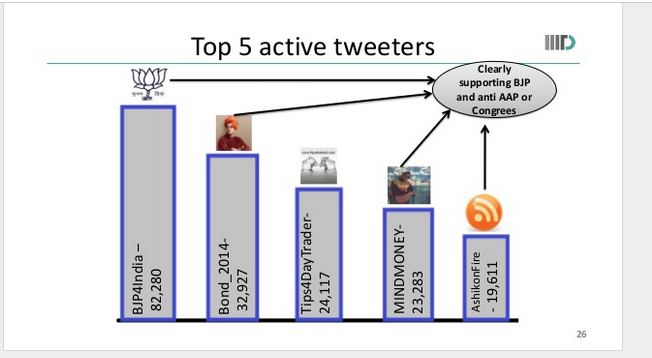

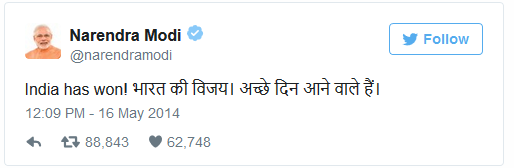

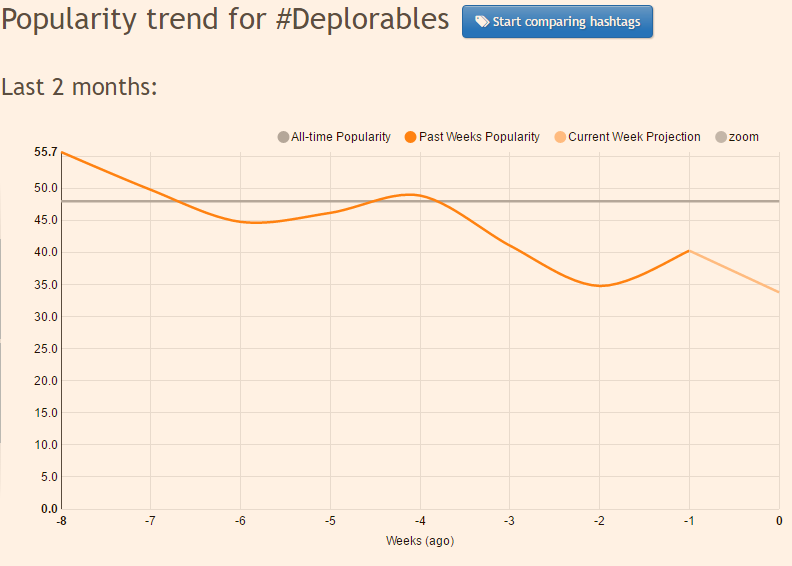

Performativity in this disembodied virtual space is reduced to profile pictures, tweets, retweets, blogs, posts, likes and shares. Political assemblies transform into social media communities, and political rhetoric transforms into hashtags. “Bhakts” and “deplorables” became the highest trending ‘tag’ that were used against any candidate in both constituencies. Bhakt is a Sanskrit word which means devotee. In the context of the 2014 General Elections in India, it connoted the apotheosis of Narendra Modi – the Prime ministerial candidate for the Hindu Right party, Bharatiya Janta Party (Indian People’s Party). His campaign team had mobilized an army of Twitter accounts (mostly fake) to campaign for their candidate and slander and heckle politicians and/or supporters of other parties. In a snowball effect, many supporters took the cue and took to social media to glorify their leader and bracket every other alternative as traitor, Muslim-appeaser, pseudo-secular and/or anti-national. The trend has continued even after the elections and dissenters are subjected to frequent online abuse. In November 2015, BJP’s Twitter army launched a campaign against a popular Bollywood actor who expressed his views on rising religio-cultural intolerance in India. The campaign asked people to boycott his films and the products that he endorses. Being a Muslim made his situation worse. It led to the termination of his advertising contract. Several others who have disagreed with governments policies or questioned its objectives have faced similar flak at the hands of these swarms of devotees. The situation would be reiterated with every activity. 5 On 16th May 2014, Modi posted what would be the Golden Tweet of the year and the most retweeted tweet ever in India.

While the keyboard wars were largely tilted in one direction in India, the Presidential Elections in the US witnessed widespread digital campaigns. Although Donald Trump was unbeatable in his bullying and name-calling (despite a limited vocabulary), Clinton’s prognosis of Trump’s followers as “a basket of deplorables”. shocked people but quickly started trending. After a long campaign that Trump ran on lies, fear and hate, no other word could describe the people who continued to support him as one after another skeleton popped out of his closet.

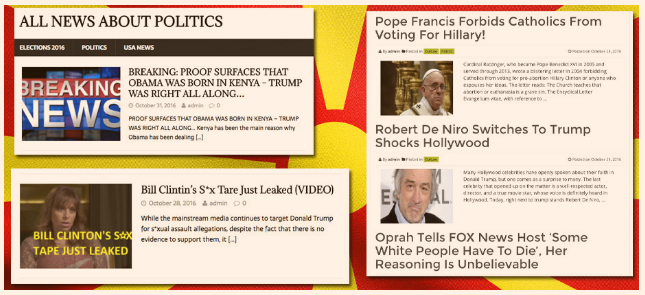

Filtering through claims of sexual harassment, misogynist statements, unfounded theories on migration-crime, blatant generalization of ethnic groups as criminals and terrorists, of women as sexual objects who “should be treated like shit”, the only sections of the demography Trump did not abuse in his campaign were uneducated working class/middle class white men. There were pro-Trump automated Twitter handles consistently tweeting false news and to their advantage there were groups of teenage content writers with absolutely no interest in the U.S. elections accept the attention economy it was generating. 6 Thus, Macedonian teens would spin and publish scandalous and sensational stories that would be picked up by Trump supporters and extensively retweeted or shared.

It appears in both cases that in an abundance of information and a decadence of research or critical thinking, people filter information based not on ideology or interest but on a certain kind of inertia that this information highway affects. More than creating bubbles of self-interest or self-preservation the propaganda creates communities and cults of a leader. The two years since the General Elections in India have witnessed a number of radical policy changes, some quite progressive and others outright blunders of management. The notion of dissent as akin to anti-nationalism still dominates social media discourse and the fickle nature of the medium prevents any intellectual debunking of these views. What turn will politics take once Donald Trump assumes office is still unpredictable. Unlike India, partisanship might dwindle once he starts backing out of his poll promises. On a lighter note as a cyborg completely incorporated within the Twitter ecosystem, his quips on China don’t bode well for diplomacy.

Image Credits:

1. Modi Trump

2. Internet Penetration

3. Trump’s Sexism

4. Top 5 Tweeters

5. Modi’s Victory Tweet

6. #deplorables

7. Macedonian Content Writers

Please feel free to comment.

- McLuhan, M. (1964). “Introduction.” In M. McLuhan, Understanding Media : The Extension of Man. London: The MIT Press. [↩]

- Lyman, Peter and Hal R. Varian, “How Much Information”, 2003. Retrieved from http://www.sims.berkeley.edu/how-much-info-2003 on 07 December 9, 2016 [↩]

- Il Messaggero. (2015, June 12). Umberto Eco attacca i social: «Internet ha dato diritto di parola agli imbecilli». Retrieved December 7, 2016, from Il Messaggero: www.ilmessaggero.it/societa/persone/umberto_eco_attacca_social_network_imbecilli-1085803.html [↩]

- Carr, N. (2008, July). “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” The Atlantic http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2008/07/is-google-making-us-stupid/306868/ [↩]

- Pal, J. (2015). “Banalities Turned Viral: Narendra Modi and the Political Tweet.” Television and New Media, 16(4), 377-386. [↩]

- Tynan, D. (2016, August 24). How Facebook powers money machines for obscure political ‘news’ sites. Retrieved December 8, 2016, from The Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/aug/24/facebook-clickbait-political-news-sites-us-election-trump [↩]