To See and Not to See: Racial Economies of Visibility and Invisibility

Roopali Mukherjee / CUNY, Queens College

More than three million viewers tuned in to a YouTube video in 2009 of two co-workers in Texas, a black man who called himself Black Desi and a white female, Wanda Zamen, testing Hewlett Packard’s new face-tracking camera. Designed to follow the object of its gaze, zooming, panning, and tilting in synchronized motion with the person being filmed, the MediaSmart webcam appeared to suffer an awkward technical flaw. Each time Black Desi entered the frame, the camera stopped in its tracks, sitting utterly still, as if unable to see him. But when Wanda, the white colleague, entered the frame, the device worked to its specifications perfectly. The bemused Black Desi noted, “I think my blackness is interfering with the computer’s ability to follow me.” “Hewlett-Packard computers,” he concluded with deadpan sarcasm, “are racist.”

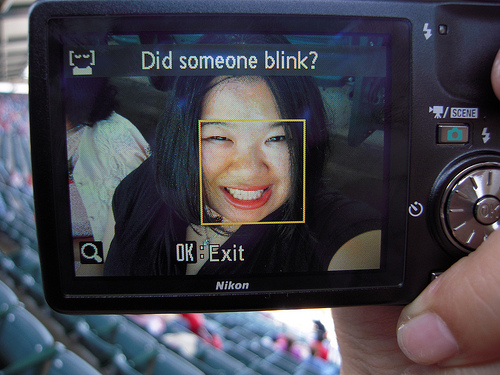

The new Nikon Coolpix S630 digital camera that Joz Wang and her brother, both Asian, had purchased as a gift for their mother appeared to suffer a similar technical malfunction. Each time the siblings took a portrait of each other smiling, a message flashed across the screen asking, “Did someone blink?” Infuriated, Wang posted a photograph of the blink warning on her blog under the title, “Racist Camera! No, I did not blink… I’m just Asian!”

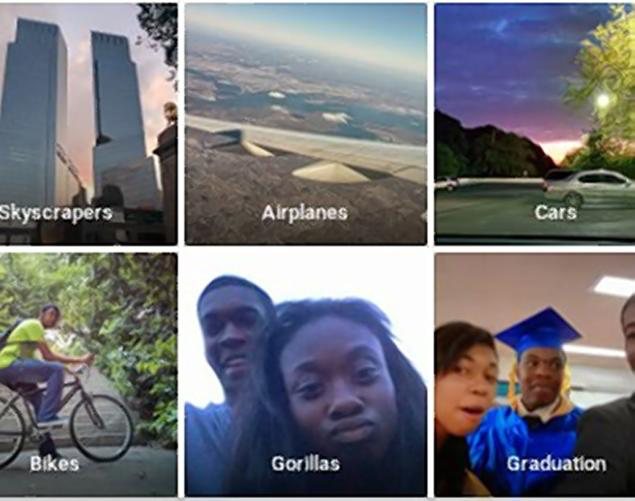

In another variant of recent technical glitches, Google’s new photo application for iOS and Android, launched in 2015, was designed to digitally “read” shapes, colors, patterns so as to decipher and catalog photographed images. User Jacky Alcine tweeted a screenshot that showed that while a number of his photographs had been accurately organized into albums like “Skyscrapers,” “Airplanes,” “Graduation,” and so on, the application had categorized photos of Alcine and a female friend, both black, as “Gorillas.”

Each of the cringe-worthy glitches in the foregoing examples specifies a malfunction, instances of blunder and misidentification, within the operating protocols of new media platforms designed to see and make visible. While they spurred a predictable rush of apologies and technical fixes from manufacturers and industry experts, these glitches reveal key modalities of misrecognition and blindness, not as malfunction but, rather, as essential to the epidermal schema of looking relations that, now, as in the past, inscribe the apparatuses of the media gaze. These are malfunctions, I want to propose, that are not malfunctions at all. Rather, key to the optic-economies of ethno-racial visibility and invisibility, they reveal everyday protocols of oversight and obscurity, of targeted seeing as well as willful disregard, that are necessary and routine within the functioning of power.

To begin, the examples signal vast and everyday operations of state and corporate surveillance that are being steadily baked into the design of networked digital media. They alert us to the ever-vigilant and capillary operations of panopticism – that “state of conscious and permanent visibility,” which “assures the automatic functioning of power”. [1] These crib-to-pyre protocols of the “panoptic sort” [2] render us decipherable, our desires comprehensible and our motivations assimilable, through actuarial composites of our proclivities – for crime (lawfulness), consumerism (frugality), dependency (independence), indolence (entrepreneurialism), political stridency (quiescence), and so on. We are permanently tracked, catalogued, watched. We are always already visible.

Formations of race and racialization remain profoundly entangled with these surveillant assemblages, easing recognition, differentiation, and discrimination. [3] [4] Key to enduring optic-economies of fear and hate, the modalities of the profile – the mugger, drug dealer, terrorist, immigrant – constitute an “extended, modern, biotech version of eugenics” [5] that derive from fugitive slave laws, sterilization practices, Tuskegee experiments, and so on to tabulations of marketing information, consumer demographics, computer usage, policy statistics, airplane passenger alerts, and public intellectual and political activist blacklists. The dangers of media technologies designed for targeted seeing, but which also misread and misrecognize, highlight enduring predicaments of racialized visibility – the dangerous sensation of standing out and calling attention that Otherness specifies and spectacularizes. [6] The tired joke of “driving while black” and “flying while brown,” Stop & Frisk programs and police killings of unarmed black men and women, secret programs designed to track sleeper cells and neutralize terrorists, and open calls to hunt “illegals” and political activists whether on college campuses or within new social movements like Black Lives Matter, each highlights the racial grammar of targeted visibility, necessary for the smooth functioning of power. Technical glitches and malfunctions are neither uncommon nor do they constitute interruptions within these architectures of seeing. Rather, they serve key operations of differentiation and discrimination geared to fateful racial allocations of the unequal costs of visibility. Panopticism is designed to recognize and to misrecognize. We are, at once, grotesquely strange and familiar.

The racial orders of these economies of visibility intersect with the prolific manufacture of commoditized, branded selves – always on display, adorned and paraded to the highest bidder, endlessly churned out as “hot commodity”. [7] Against “circuit-breaker” modes of “sousveillance,” tactics used to render one’s self out of sight [8] [9], and which hold the promise of imperceptibility and opacity as modes of racial resistance, the branded self of promotional culture jostles to stand out, straining to be seen. Tracking the visual economies of commodity racism, the “to-be-looked-at” black subject capitalizes on racial currencies with endless iterations of thrilling athleticism, exotic depravity, and/or fetishized abjection. [10] [11] Enshrined within commodity circuits of voyeurism and prurience [12], these are brands that shore up profitable circuits of racialized visual pleasure – in music videos, on reality TV and the evening news, in must-see spectacles of deadly racial violence captured on cellphones, dash-cams, body-cams, and so on. Each one trades in gripping spectacles of black stigma and allure, of suffering, trauma and, indeed, of death. Invisibility equals death. If you do not see us, we cannot exist. We must always be visible.

These brand technologies of the self organize protocols of “technical management” geared to sorting those who matter while attentively weeding out those who do not. These modalities of assessment are designed to identify those that are “inferior” – the lost cause and the poor risk, the unassimilable and the unreformable – as harmful to the larger population, and as subraces that can – and must – be left to die. [13] Tracking biopolitical operations of willful disregard, these economies of invisibility order and fuel vast growth industries of triage and neglect – the out-of-sight warehousing of millions in the prison-industrial complex; dark armies of the vulnerable, the poor, the unemployed and underemployed; the ill-equipped or unwilling whose abandonment takes shape as good business (and political) sense. Far from malfunction, these modalities of disregard emerge crucial to organizing and reifying powerful epidermal schema of differentiation and discrimination. Precarity hinges on an evaluative triage. When we do not matter, we become invisible and are left to die.

As vigilant visibility meets biopolitical imperatives for a selective and attentive blindness, the racial labors of these looking relations, always on the move, shore up fantasies of the “post-racial,” the willed unseeing of race as a consequential mode of inequality and oppression. This is an invisibility that renders absurd the means to articulate ethno-racial grievance, and to organize redress against its burdens. We face an untenable enforced opacity. We are, at once, spectacularly visible and assiduously unseen.

These economies of visibility and invisibility embed visual grammars, which, far from neutral to the question of race, are themselves “a racial formation, an episteme, hegemonic and forceful”. [14] Marketizing fear and commoditizing vigilance, branding allure as well as stigma, their protocols of attention, and, indeed, of malfunction, reveal enduring epistemic logics of surveillance as a racial practice.

Image Credits:

1. Technical flaw in Hewlett Packard’s face-tracking camera

2. Nikon Coolpix S630’s erroneous blink warning

3. Google photo application misreads images

Please feel free to comment.

- Foucault, Michel. 1977. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage. [↩]

- Gandy, Oscar. 1993. The Panoptic Sort: A Political Economy of Personal Information. Boulder CO: Westview. [↩]

- Ahmed, Sara. 2004. “Affective Economies.” Social Text, 22(2): 117-139. [↩]

- Browne, Simone. 2015. Dark Matters: On The Surveillance of Blackness. Durham NC: Duke University Press. [↩]

- Puar, Jasbir K. 2011. “‘The Turban is Not a Hat: Queer Diaspora and Practices of Profiling.” In Patricia Clough and Craig Willse, eds. Beyond Biopolitics: Essays on the Governance of Life and Death. Durham NC: Duke University Press, 65-105. [↩]

- Fanon, Frantz. 1967. Black Skin, White Masks. New York: Grove, 109-140. [↩]

- Bauman, Zygmunt. 2007. Consuming Life. Oxford: Polity. [↩]

- Deleuze, Gilles. 1995. “Control and Becoming.” In Negotiations, 1972-1990. New York: Columbia University Press, 169-176. [↩]

- Mann, Steve, Nolan, Jason and Wellman, Barry. 2003. “Sousveillance: Inventing and Using Wearable Computing Devices for Data Collection in Surveillance Environments.” Surveillance and Society, 1(3): 331-355. [↩]

- Diawara, Manthia. 1993. “Black Spectatorship: Problems of Identification and Resistance.” In Manthia Diawara, ed. Black American Cinema. New York: Routledge, 211-220. [↩]

- Mulvey, Laura. 1975/1999. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” In Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen, eds. Film Theory and Criticism: Introductory Readings. New York: Oxford University Press, 833-844. [↩]

- Hartman, Saidiya. 1997. Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-making in Nineteenth-century America. New York: Oxford University Press. [↩]

- Clough, Patricia and Willse, Craig. 2011. “Beyond Biopolitics: The Governance of Life and Death.” In Patricia Clough and Craig Willse, eds. Beyond Biopolitics: Essays on the Governance of Life and Death. Durham NC: Duke University Press, 1-16. [↩]

- Butler, Judith. 1993, “Endangered/Endangering: Schematic Racism and White Paranoia.” In Robert Gooding-Williams, ed. Reading Rodney King, Reading Urban Uprising. New York: Routledge, 15-22. [↩]

Thank you for tackling this increasingly relevant topic. All of the examples of technical glitches above were completely avoidable before the product releases, and so on some level “routine within the functioning of power” as you describe. Does the panoptic gaze classify people of color as dangerous or irrelevant or both? And if I were to put on my social sciences hat for one more question: how do we attempt to avoid the continuation of such racial formations?

I’m wondering about the extent to which people of color were actually involved in creating these technologies, and whether increasing the number of black people in tech would help stop these sorts of oversights.

Pingback: Hologram—Pepper’s Ghost | yc777blog

Pingback: Are Motion Tracking cameras “Racist”? – Social Aspects of Gaming