One Hundred and One Sinkholes: Notes on the Film Loop

Josh Guilford / Amherst College

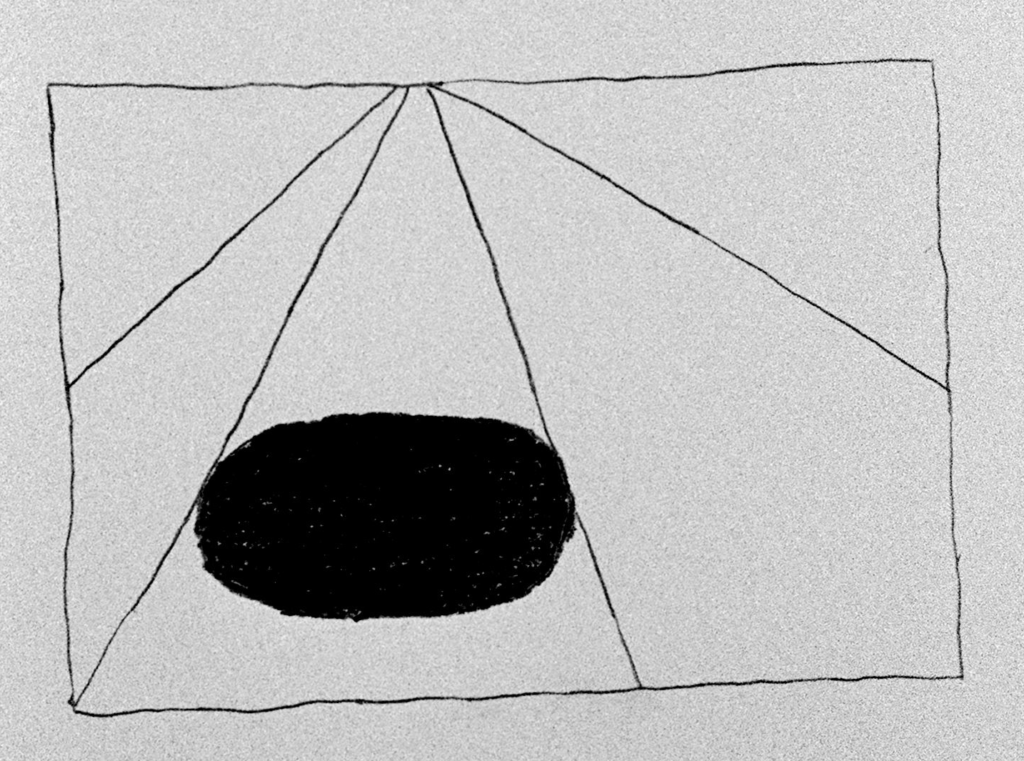

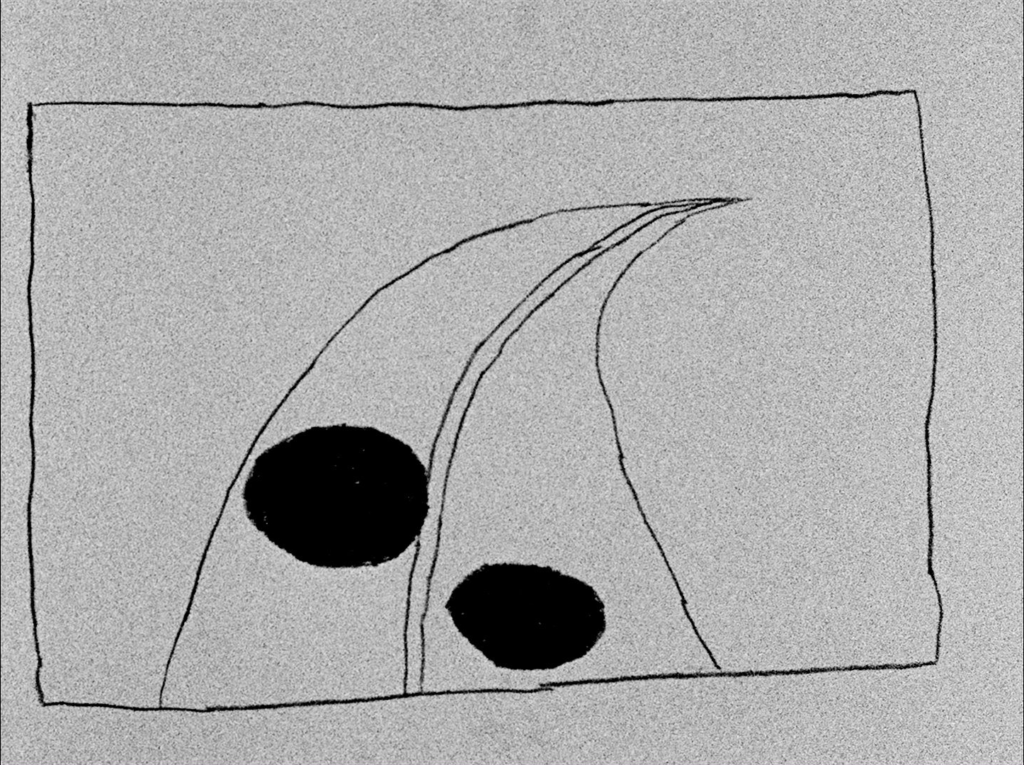

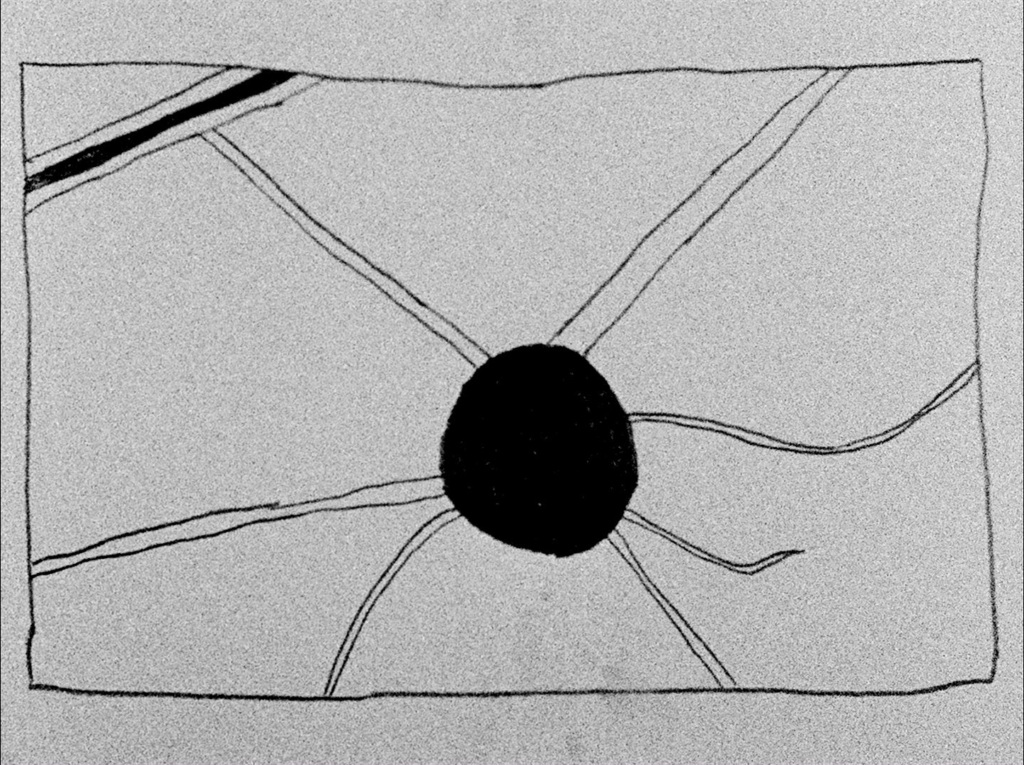

Upon entering a recent exhibition by the artist Jenny Perlin, the viewer confronts an unsettling display: a freestanding wall made to hold one hundred sinkholes. Arranged with deceptive uniformity in a ten-by-ten grid across the wall, the sinkholes are drawn in a minimal style on small rectangles of paper, monochromatic blots of colored ink that render, abstractly, actual sinkholes in the world. Many are accompanied by mysterious lines, straight or curved, which extend to suggest some arbitrary point in the built environment where a given sinkhole intervened. The blots seem to dislocate the lines, appropriating the frame and making the lines appear fragile and meager, like vague memories of a grand, infrastructural ambition, some dream of rationality dispelled by terrestrial collapse.

Stepping past the display into the dark room behind, one finds a 16mm projector modified to hold a looper with a black pool of celluloid continuously gathering, escaping from the platter on top. The film, which is thrown onto the rear surface of the wall separating these spaces, presents images of the same sinkholes rendered in graphite and arranged in a linear sequence. Each drawing emerges in steps through a process of single-frame animation, then holds momentarily as an image before giving way to the next. The runtime of the film is just over 14 minutes, but the print is joined end to end, with no title card to designate a beginning or conclusion. One after another, a hundred sinkholes cycle in an unbroken loop, surfacing relentlessly but accumulating nothing, emerging to collapse, emerging in collapsing. Through circularity, the film’s time is made to fold, returning by extending forward, progressing to return. Each new image becomes an echo and the gallery itself a sort of eddy that echoes the swirl of celluloid atop the projector. Between the viewing space and the images onscreen, a resonance arises: time as a blot suspended in the white cube.

In both its content and its form, Perlin’s film – 100 Sinkholes (2014), from the exhibition One Hundred Sinkholes (2014) – would seem to affirm an intriguing complicity posited by Maurice Blanchot between the artwork and catastrophe. Examining art’s pursuit of an aesthetic realm separate from reality, Blanchot writes of the work of art as an unworldly thing, an alien arrival summoned by that which “puts the world into question.” “[E]verything that surpasses, denies, destroys, threatens the body of relations that are stable, comfortable, reasonably established, and anxious to remain,” he explains, “work[s] for art, open[s] the way for it, call[s] it forth.” The work of art, Blanchot contends, thrives on interruption, on forces of destabilization that “shatter the validity of the common world.”1

In this short article, I would like to propose the film loop as one such world-destabilizing force. If “world” is conceived in both concrete and imaginary terms, as “that space of practical life but also of truth as it is expressed, of culture and significations,” then the loop’s capacity to disturb routine modes of practice and habitualized modes of perception does render it a potential threat to the world2 . The loop can facilitate experiences with the moving image that allow one to stretch or fray the practical and psychic fabric of daily life, opening a seam through which to glimpse other forms of living and relating.

Given the loop’s resurgence as a privileged exhibition form within contemporary art, and the central role looped projection has played in what Erika Balsom has referred to as the “increasing spectacularization of the museum space,” it may seem naïve to argue for the loop as an interruptive technology3 . When viewed from the galleries of the late capitalist museum, the loop appears as a decidedly worldly phenomenon, a medium of perceptual intensification thoroughly embedded in the financial and attentional economies that undergird contemporary exhibition cultures. But the loop harbors a potential to disturb these economies. It offers a strange, abrasive time that erodes the temporal ground of the common world, providing an occasion for the viewer to slip away from the experiential continuum of daily reality. This erosive temporality – constant, repetitive, mechanical – renders the loop a sort of slow expulsive force, one capable of putting the viewer not violently, but gradually “outside the world, outside the security and intelligence of the world…”4

The temporality of looped projection can facilitate an alternative viewing practice that swerves from conventional modes of relating to the filmic image. Looped installations organize the time of filmic exhibition as an open, durational expanse structured by perpetual repetition. They evoke a “forever repetition,” as the artist Shambhavi Kaul recently remarked – a temporal form that suggests “a cinema playing for nobody.”5

This open, recurrent, and seemingly inhuman temporality contrasts markedly with the linear and singular structure of traditional cinematic screenings. Unlike the standard moviegoer, who arrives to the theater at a set time, attends to the film as it unfolds, and leaves when it concludes, visitors to a looped installation may choose to view a given work multiple times in a single sitting. This makes the loop a rare context for repeat engagements with films that can be difficult to access, let alone view repeatedly. By providing such a context, the loop can encourage a nuanced appreciation of a film’s internal structure, which often passes unnoticed on an initial viewing.6 But it can also catalyze a distinctly pleasurable attunement to the polyvalent character of the moving image, allowing the viewer to wait and watch as a film shifts over time, revealing itself as a complex nexus of different readings, problems, gestures, balances: a sort of tangle laden with opacities to be teased out and let loose, resumed, mulled over.

The loop’s capacity for repeat viewing may seem to align it more closely with the private and domestic viewing practices facilitated by electronic media technologies. As Laura Mulvey has noted, these technologies do cater to an enduring “repetition compulsion” provoked by the cinema, easing the viewer’s ability to replay privileged moments within a film and thereby attain a sense of mastery over the image.7 But as Kaul’s remark suggests, the practice of sitting inside the “nobody cinema” opened by looped projection must be distinguished from such personalized and domesticated experiences of repetition. Whereas users of such devices perform repetition themselves, affirming self-possession via a possession of the image, the viewer who chooses to remain with a loop relinquishes control, subordinating her or his time to that of the apparatus. Rather than a user, this viewer is closer to a visitor, with all the connotations of externality this term implies. Such a visitor engages in a practice of being-with, a sitting-alongside in a time of estrangement, the yield of which is strangeness itself.

To be sure, the loop’s invitation to duration is generally declined. As Laura Marks observes, the typical viewer of a moving-image installation stays “just long enough to get ‘an idea of it,’” wresting some minor cognitive reward from the work installed before moving on to something else. Whether prompted by the call to mobility conveyed by the museum’s expansive architecture, the anxiety of completion this architecture induces, or the poor viewing conditions it tends to provide, the distracted museumgoer enacts a viewing practice that tends to reduce the loop’s durational form to a mere “idea of duration,” a potentiality that is largely unutilized in practice.8

But duration is there in the loop if you want it. And looped projection can encourage extended viewings that contrast with the distracted itineraries promoted by the museum, drawing viewers into a mesmerizing, vertiginous engagement with the moving image that few other media technologies can approximate. This is most clear when a linear work made for theatrical exhibition is projected via the non-linear form of the loop. Here, the viewer, who inevitably enters the film in some indeterminate middle zone, watches the film conclude and begin again, projecting this beginning backwards in time to imagine how it would read when positioned before the conclusion, while looking forward to a middle whose moment of arrival is unknown. When this point of entry does return, it returns with a difference, now recontextualized and renewed, invested with a new significance, made to signify differently. It concludes one’s viewing of the work but fails to function as a conclusion, instead giving way to the return of the conclusion, itself different again and somehow incomplete without reviewing the beginning.9

In such cases, the loop’s structure generates a complex, heterogeneous temporality that facilitates a disorganized viewing experience mediated as much by projection and retrospection as by the presentness of perception. When given the time, this temporality can catalyze a deliberate unraveling of the imperative to immediacy at the heart of contemporary culture. If the latter is increasingly guided, in Jonathan Crary’s terms, by a “hallucination of presence” that envisions human life as “an unalterable permanence composed of incessant, frictionless operations,” the loop can help to blot out this vision, allowing the viewer to puncture the operational surface of communication and sink into the “victorious strangeness” of an otherworldly time.10

* This article originated as a paper presented at “Codes and Modes: The Character of Documentary Culture,” a conference held at Hunter College, City University of New York, November 7-9, 2014.

Image Credits:

All images courtesy of Simon Preston Gallery, New York.

- Maurice Blanchot, “The Museum, Art, and Time” in Friendship, trans. Elizabeth Rottenberg (Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 1997), 23. [↩]

- Ibid. 33 [↩]

- Erika Balsom, Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art (Amsterdam: Amsterdam UP, 2013), 31. [↩]

- Blanchot 33. [↩]

- “In Conversation: Shambavi Kaul with Jordan Cronk,” Brooklyn Rail, 3 May 2016, http://www.brooklynrail.org/2016/05/film/shambhavi-kaul-with-jordan-cronk. [↩]

- Other experimental filmmakers have sought to utilize this aspect of repeat viewing in works designed for theatrical exhibition by repeating an entire film multiple times on a single exhibition print. Peter Kubelka is most notable here for making works such as Adebar (1957) available for distribution on reels containing an individual film two or five times, and for requesting that such films be viewed at least twice in sequence. For Kubelka, repetition serves, somewhat paradoxically, both as a means of memorization, where the spectator is encouraged to get to “know [a film] by heart,” and as a reminder of nature’s basis in perpetual change, where one’s constantly varying perception of a repeated occurrence is valued for its ability to provoke ecstatic dream-states. See the Film-Makers’ Cooperative’s online catalogue at http://film-makerscoop.com/rentals-sales/search-results?fmc_author=438; and Peter Kubelka, “The theory of Metrical Film” in The Avant-Garde Film: A Reader of Theory and Criticism, ed. P. Adams Sitney (New York: NYU Press, 1978), esp. 154. [↩]

- See Laura Mulvey, “The Possessive Spectator” in Death 24x a Second: Stillness and the Moving Image (London: Reaktion Books, 2006). [↩]

- Laura U. Marks, “Immersed in the Single Channel: Experimental Media From Theater to Gallery,” Millennium Film Journal 55 (Spring, 2012), 21. [↩]

- This viewing experience is not exactly novel. As Stanley Cavell reminds us, it was relatively common before cinema adopted the theater’s more regimented exhibition structure. Writing in 1971, he complains of the negative impact that the formalization of moviegoing was having on both the private and public dimensions of cinematic experience: “One could say that movie showings have begun for the first time to be habitually attended by an audience, I mean by people who arrive and depart at the same time, as at a play. When moviegoing was casual and we entered at no matter what point in the proceedings (during the news or short subject or somewhere in the feature—enjoying the recognition, later, of the return of the exact moment at which one entered, and from then on feeling free to decide when to leave, or whether to see the familiar part through again), we took our fantasies and companions and anonymity inside and left with them intact. Now that there is an audience, a claim is made upon my privacy… I feel I am present at a cult whose members have nothing in common but their presence in the same place” (Cavell, The World Viewed, enlarged edition [Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1979], 11). [↩]

- Jonathan Crary, 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep (New York: Verso, 2013), 29; Blanchot 23. [↩]

Incredible movie to watch.

A friend just passed this along. So interesting!