The Hunger Games and Obama’s “Post-racial” America

Camille Debose / DePaul University

Last summer I became aware of the growing buzz surrounding The Hunger Games. It seemed to be on everyone’s recommendation list. My son, thirteen at the time, was being encouraged to read it by his peers. I was being told to read it by various adults in my community. Not being one to raise my nose at young adult novels I loaded the audio versions of the books onto my iPod and spent several days taking long walks with the baby while listening to the exploits of Katniss Everdeen. I was hooked, drawn in not by the burgeoning love triangle between Katniss, Peeta, and Gale, instead I was hooked on parsing the socio-political commentary embedded within the story of a girl who’s really good with a bow and arrow.

Huffing and puffing along the lakefront path I decided a Marxist read was too easy. This class based struggle between the hungry proletariat and the strangely glittering bourgeoisie of the Capitol (a place not unlike L. Frank Baum’s Emerald City) is glaringly apparent. The “evil-ness” with which the bourgeoisie is imbued is clearly defined. The reader (or in my case, listener) is unsettled by the Capitol’s vile taste in entertainment; children fighting to the death. Collins’ bourgeoisie is also morally and perhaps spiritually bereft indulging in gluttonous adornment and body modification for fashion fun while having no deeper consideration for the citizens in the districts beyond who will win the death match. Accompanying this discussion of class hegemony is a strong anti-war sentiment. To be clear, a Marxist read of this text is not without value. On the contrary, there are lots of little tidbits and nuggets for analysis but on my walks with the little one I decided to go further because there is something truly radical about the series that I wish to discuss. A radical Snark that begs hunting.

Katniss is female. She is a female protagonist in a post-apocalyptic, dystopian, adventure series which contains lots of weapons, fighting, and bloodshed and (spoiler alert) she is winning. She makes it clear that she never wants to fall in love and she never wants to get married and she never wants to have babies. There. Done. These assertions open the door to conflict perspective discussions of the institution of marriage, the institution of motherhood, masculine hegemony, heteronormativity, and the overall expectations linked to womanhood. Like the discussion of Class above I decided to bracket Gender. A young woman eschewing the virtues of marriage and motherhood is not radical. It is worthy of note if you are attempting to impress upon contemporary teens they are not required to marry and pop out babies. It is also useful when creating conflict in the story by setting up an inevitable reversal. Furthermore, Katniss’ stiff arm of traditionalist sex roles is not radical because it is possible and plausible in the post-apocalyptic Districts as well as our own contemporary context. So, I pushed Gender aside for another time and continued down the path toward the toddler event horizon. The point before which I must turn back toward home or risk the exhaustion of our supply of Goldfish and lemonade leading to my precious offspring going supernova.

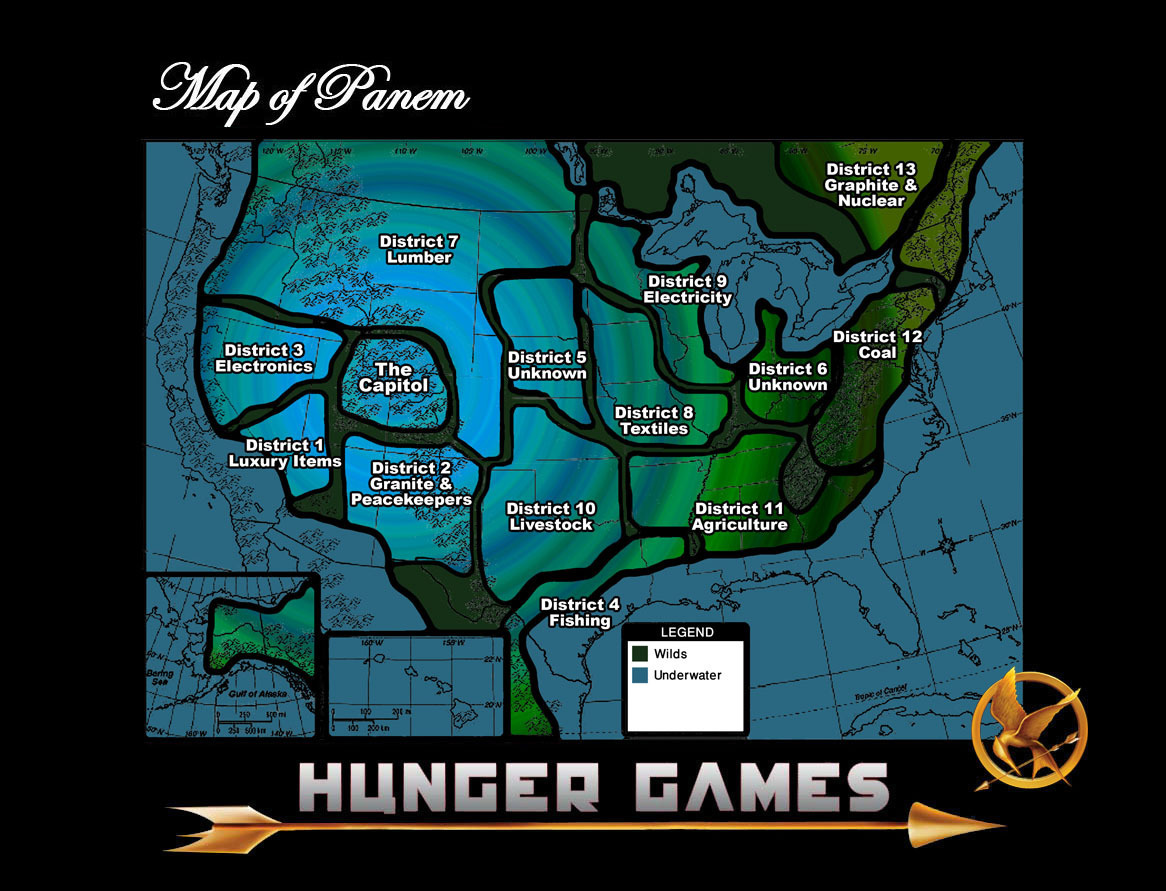

With two constructs down my thoughts turned to Race and in the distance I thought I saw the shimmering back of the beast. I’m embellishing of course. There are no beasts along the lakefront path unless you count ducks and geese. Nevertheless, if radical is the Snark then Race in The Hunger Games fits the bill. This is not pop culture’s “radical.” To borrow from Stephen King, pop culture has forgotten the face of its father when it uses the word. This is the real radical, meaning, for the espoused (post-racial) reality to exist the complete destruction and dismantling of the current structures of power must occur because power doesn’t live on the skin. It lives in the bones. In the post-apocalyptic world of The Hunger Games, Race is not tied to power. There are active structures of domination at work in Panem1 but Race does not play a role. Each of the twelve districts is inhabited by a different “ethnic” (loosely based upon phenotype) group. All twelve districts serve the capital. All twelve districts are subject to the reaping. No group is safe from the Capital’s caprice.

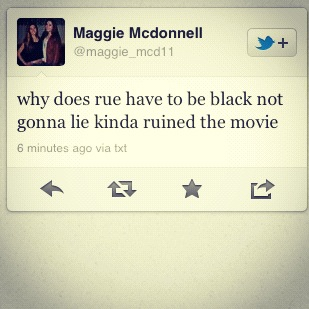

Once the games begin these groups are thrown together in a fight to the death for the pleasure of the Capital and its citizens. Our olive-skinned heroin (more on this later) forms a kinship with a little girl from District 11 named Rue. In Rue, Katniss sees a mirror of the beauty and innocence of her little sister Prim and is compelled to protect the child. Katniss is so enamored of the girl you can almost hear the faint plucking of harp strings whenever Katniss considers Rue. The author’s description of Rue is clear. Dark, brown skin. Dark eyes. I read this as “little, black, girl.” Apparently many readers of the series missed, by willful blindness or sheer stupidity, the clear descriptions of Rue and the people of District 11. Here the real and the imagined anxiously collide and one Snark meets another. After viewing the film version several of our fellow Americans took to Twitter and the Blogosphere to declare that the “surprise” casting of Rue as a black girl made her death so much less sad. Again, my only response to this is willful blindness or stupidity, but the snarky comments are worth assessing. Denby puts it plainly. “At the end of the first decade of the twenty-first century, snark sounds like the seethe and snarl of an unhappy and ferociously divided country. A country releasing its resentment in rancid jokes.”2 At a time when many have declared the U.S. post- race presenting as evidence the election of Barack Obama, The Hunger Games throws in sharp relief just how absurd such claims of post-raciality are.

For Williams “…it is not merely the silence about racism that presents problems but its aesthetic visual power as well. Thus I believe that racial representations in popular culture present a most urgent concern in a society as relentlessly bombarded with visual images as ours.”3 There was a noticeable lack of snark and complaint regarding the casting of Katniss as white when in fact she is described, as I mentioned above, as olive-skinned. I don’t know if the actress who portrays Katniss considers herself white but she ‘looks’ white and in a visual medium, which cinema is, what one looks like is quite important. We can assume the peeling away of Katniss’ “color” was not accidental and go further to suggest it as a form of symbolic violence. Seeing Katniss as white onscreen was not disturbing even though she is described with olive-skin by the author. Seeing Rue with brown skin was disturbing even though she is described with brown skin by the author. So. Is America post-racial, or not?

In the world of The Hunger Games I glimpse my Snark. Within the story world the radical destruction of North America and the reconstruction of Panem post-raciality is. Hegemony rises from Class, not Race. In Obama’s America the Snark eludes me. Tim Wise suggests “Obama’s election, far from serving as evidence that racism had been defeated, might signal a mere shape-shifting of racism, from Racism 1.0 to Racism 2.0, an insidious upgrade that allows millions of whites to cling to racist stereotypes about people of color generally, while nonetheless carving out exceptions for those who, like Obama, make us comfortable by seeming so “different” from what we view as a much less desirable norm.”4 Wise goes on to assert our confusion about being post-racial, if not precipitated by, is exacerbated by President Obama’s current and past political rhetoric. When we call for a radical shift in our collective ideologies do we know what it is we are asking for? A post-racial reality in America, even one led by a black man, would take something akin to an extinction level event, decimating current socio-political structures. I don’t know about you but I have witnessed no such event. Let us then cease with these faulty claims of post-raciality. In The Hunger Games, Panem is radical. We are not. Post raciality, for us, is a Boojum, you see.

Image Credits:

1. The Hunger Games

2. The Cast of The Hunger Games

3. A Reader-Made Map of Panem

4. One of Many Tweets

Please feel free to comment.

- Panem is the post-apocalyptic remains of North America in the Hunger Games story universe. [↩]

- David Denby, Snark (Simon & Schuster 2009). [↩]

- Patricia J. Williams, Seeing a Color-Blind Future (The Noonday Press, 1997). [↩]

- Tim Wise, Color-Blind, The Rise of Postracial Politics and the Retreat From Racial Equity (City Lights Books 2010). [↩]

Camille Debose article on Hunger Games is cogent and stimulating. Indeed this ” dystopic and post apocalyptic text can be read as an allegory for contewmporary US society. Indeed the point that this society fails to pass the post-raciality test is well argued. I consider however that there is another aspect in Hunger Games that raises the problematic of” the society of the spectacle”which Guy Debord elaborated in the 70s.In Panem power is exercised through subjecting the masses to watch a reality show in which people are killed. The myth of Tesseus and the Minotaur has been updated to signify modern societies in which killing becomes the absolute spectacle.With Fox news having played such a crucial role in the emergence and strengthening of the Tea Party, the US turning into a society of the spectacle seems a poignant allegory.

Maria. What a wonderfully intriguing addition- “…another aspect in Hunger Games that raises the problematic of” the society of the spectacle”which Guy Debord elaborated in the 70s.” While the text was/is consumed as a popular text I find it to be fertile ground for discussions of the social, the cultural, as well as the political. I will take a look at the story with a new eye using Guy Debord as my lens. Thank you.

Great post – and very intriguing! I just finished “reading” the series, also on audio book (I’l never say the word “capitol” the same way again!) I was aware of a casting controversy, but didn’t realize the extent of it! What might be interesting to consider is the level of control the author had in casting decisions — she is, after all, the screenwriter for the film!

Great piece Camille. I must confess that I am among the three people on the planet who has read nor listened to these books, but am well-aware of the hullabaloo over casting a black actor in one of the roles. But I wonder how far we can trace this notion of Racism 1.0 to Racism 2.0 Wise discusses. In some ways, Sut Jhally and Justin Lewis assert that some white viewers saw The Cosby Show as having transcended race because they were “our kind of people,” yet were still considered apart from the rest of the undesirable black people who were victims of Reagan’s economic policies. But a wonderful analysis! Thanks for the contribution.

I agree Taylor. I wonder if there was ever a consideration of casting an actor with darker skin as Katniss. I suspect not. Diversity which works in a novel won’t necessarily translate well to screen due to audience considerations. As for the flap over the casting of Rue, well, that wasn’t so much controversial as ridiculous.

Alfred, your point is very, very interesting. To push Wise’s theory to 2.5 or even 3.0 forces greater nuance in the consideration of a willful blindness or bracketing of “color.” Hmmm.

Pingback: By the Book: The Hunger Games | Stars in Her Eye

I’m about half way through the last book Mockingjay and love the whole series, I’ll be very sad to see it end. I did not pick up on a race issue in the story, but I think people can superimpose whatever class distinction they are most sensitive to. What makes the book very real to me, is that I just finished a book called Half the Sky: Turning Oppression into Opportunity for Women Worldwide. The PBS show Independent Lens will have a related documentary airing early October, http://www.pbs.org/independentlens/half-the-sky/

Reading Mockingjay after finishing Half the Sky, I’m convinced its the same message. How can people of privilege, such as us in the USA, ignore the plight of others suffering to provide us the luxuries we enjoy (gold, precious metals, electronics, clothes)? Well this isn’t the actual focus of the Half the Sky book, but the connection is stark to me. I am wondering if anyone has that connection?

A thought-provoking piece Camille. Thanks. The shift to a more ‘racialised’ discourse once the story is made visual was very interesting.

I also read and watched The Hunger Games with an eye on the racial politics. In fact, I saw the film first, unaware of the controversy over Rue’s casting and just supposed the book made it clear that she was black. Which indeed it does, but without much weight given to the fact. I’m sure there’s plenty we could invent about why Panem has ended up with different racial groups in different, separated districts (that doesn’t seem very post-racial). But more to the point, there was a few difference between book and film that made race stand out as problematic for me.

One such interesting (arguably necessary) divergence is the cut in the film to general rioting in Rue’s district after she has died. While in the book, told as it is from Katniss’s point of view and in the present tense, we don’t learn of any such rioting until book 2, and then only as hearsay, in the film, Katniss’s heroisation of Rue as she lays her dead body to rest surrounded by flowers acts as a symbolic ritual that sparks angry rebellion in district 11. Although if you’ve read the books you might assume this will prove to be the opening battle of an ensuing revolution, in the context of the film (and specifically in the fleeting, unexplained and generic way in which it is filmed) the riot appears as unthinking, angry chaos. Compared to the controlled and (literally) contained violence of Katniss in the arena (i.e. war), district 11 bears a striking resemblance to un-military, unofficial and un-watched and black(ened) violence of recent real-world ‘rioting’. It resounds with the imaginary nightmare of ghettoised cities out of control. The abandoned New Orleans’ state of lawlessness after Katrina or, for a British viewer, the riots in poor and ‘black’ areas of London and other cities in the Summer of 2011 (still fresh in the memory when the film was released here a few months later). These events are most unsettling for the more privileged onlooker because of their inability to be shown – sketchy news footage from helicopters far off in the sky, politicians unwilling to enter the scene of chaos, the rioters themselves doing nothing for show, but for personal gain or to settle grievances against an equally faceless authority. The riot in district 11, we must presume, is not so selfish, but it is, after all, precisely unseen by Panem (unlike the Games), and is barely seen by us the audience, as we’re given a few shots to leave us in no doubt that black people are rioting, but nothing much beyond that. While the furore over casting Rue as black does indeed seem absurd, the addition of that scene, giving the audience a glimpse of the violent black stereotype, but allowing it no further explanation or identification than a foreshadow of the main revolutionary event (which will be multi- and therefore non-racial), seems to play on racist expectations that are very much part of the current, real-world climate.

It will be interesting to see what happens to race in the films as the revolution itself unfolds. What race(s), for example, might comprise the population of district 13?!

Sam I agree wholeheartedly. I’ve reserved discussion of the riot scene because I’m curious to see how this will impact/manifest in the second film. I have no doubt the first film was adapted with an eye toward the second. If we combine what we see of district 11 in the film with what we know occurs in the second book, it could be (this is a leap, I know) that we’ll see the valorization of district 11. They will be the first district to rise up in defense of the fallen child and the other districts will follow suit. Rue is given such symbolic value that she is worth revolution. So the jury is out.

Your final point is indeed interesting. What will happen when suddenly the groups are mixing and mingling? Also, will the bodies we see be proportionate to the size of the prior district or will we predominantly see white bodies in district 13? I guess we’ll all stay tuned. Thank you for your comment.

Pingback: Dystopian panem et circenses | Life as Improvisation

Hi there.

I am a fan of both the books and the movie. I have yet to finish the third book, but I still consider myself very involved with the series including the motion picture. As the series continues, I will continue to follow the motion pictures as I am a film student and am very connected with the characters in the story.

So let me start off. I am a 3rd year Film Student attending a University here in the United States. I am 21 years old. I am not sure if it is our generation or not, but I know that my friends and I were very surprised to see all of the uprise about the casting in the Hunger Games film. I was completely unaware it was even an issue, and many of my fellow students and I had never even considered the issue as we watched the film in the first place in theaters months ago. The thing is, our generation is different. It is changing. We consider the entire “race” and “racism” thing, a thing of the past. I have never, in my entire life, judged someone on the color of their skin and I have continued this attitude for my entire life. I never even notice it anymore. People are: people. That is it. End of story. That is how many if not all of my friends and family have acted since I was a young kid and I look down upon others who are racist. That being said, on screen controversies such as this one always seem to raise an eyebrow. I didn’t even notice the color of Rue’s skin when I watched the movie in the first place because like I said, people are people. Now that I take a second look at the scene, I can see where people would be offended, but I am sure this was not the intention of the writer or the director. As stated in the article, the book even said she was darker skinned so it was not a surprise when Rue was dark skinned in the movie. The Hunger Games is supposed to be a fictional story of what our future (which it hopefully doesn’t turn out to be) could look like with all of the hostilities of class and money. As portrayed in the book and movie, Panam is a country solely based on that fact, not race in any way.

In conclusion, it is only true to say that Rue was selected just the way everyone else in the movie was casted. As a person. Not as a symbol of something that is raciest. That was not the point of the story. The point was to prove that later racism and power COULD turn into who has the most money, and prejudice based on race is a thing of the past- which it is already becoming.

Very interesting article.

You argue that “the peeling away of Katniss’ ‘color’ was not accidental.” I would argue that the choice to cast Jennifer Lawrence as Katniss had less to do with intentionally stripping away racial characteristics than with the fact that Jennifer Lawrence was very in demand, and was actually very good for the part (as her performance in Winter’s Bone would indicate).

The Hunger Games takes place in a future dystopia, where everyone seems to have been stripped of any cultural aspects of of modern racial identity. There are no mentions of Latinos, Blacks, Arabs, Asians, etc. The only thing that might hint at what cultural heritage the characters are descended from is the mention of their skin color. So, in a future where everyone is essentially wiped clean of any specific racial identity outside of their District identity, does it really matter what color the actors are that portray them? Perhaps it might violating authorial intent, but a lot of small changes were made in the adaptation process.

But it does raise the question: Is it really worth looking at The Hunger Games through a modern racial lens? Or does doing so cause us to see patterns where there are none?

The book says that Rue has brown skin, so I don’t understand why anyone was upset in the first place. Many Black people have brown skin. I’m amazed by the low reading comprehension skills of most people.