Some Notes on Streaming

Wheeler Winston Dixon / University of Nebraska, Lincoln

Right now I’m working on a new book: Streaming: Movies, Media and Instant Access. So I’d like to preview it here, in my first column for Flow, to put my stamp on it, for one thing, but also to sketch out some of the recent developments in streaming technology, particularly as it applies to the moving image. Netflix built its business model on delivering DVDs to the doorstep of its customers; this effectively killed Blockbuster Video’s brick-and-mortar, “go to the store” model, just as Amazon did with books, thus wiping out a large number of independent bookstores, even large chains, throughout the world.

But on November 22, 2010, Netflix announced it would offer a streaming-only service to viewers, and simultaneously hike the subscriber price of physical DVDs that are rented through the mail. Clearly, Netflix wants to do away with DVDs altogether. As Netflix’s CEO, Reed Hastings, said in a statement of company policy on that date, “we are now primarily a streaming video company delivering a wide selection of TV shows and films over the Internet”1.

At the same time, Bloomberg News reported that “The price increase lets Netflix pass on rising postage costs and protect average revenue per customer as more subscribers choose streaming only, which is more profitable . . . The streaming-only plan, priced at $7.99 a month, had been tested in the U.S. after a similar option started in Canada two months ago surpassed expectations . . . The subscription price for unlimited streaming and one mail-order DVD at a time will increase to $9.99 a month from $8.99, Netflix said. The cost to have more DVDs at a time will also go up. The price change takes effect now for new customers and in January [2011] for existing customers”2. For a physical DVD, there are always the ubiquitous Red Box vending machines, but they stock only the most current hits.

So, what about all the classic films that aren’t available as streaming video? In essence, they will cease to exist. Netflix is banking on the fact that most people have no real knowledge of film history, and so they’ll content themselves with streaming only the most recent and popular films. This is something akin to Amazon deciding to do away with physical books altogether, and offer everything only on Kindle. No doubt Amazon is thinking about this possibility, and would love to do it, but to do so would marginalize literally hundreds of thousands of books.

After killing off all the brick and mortar stores for DVDs, CDs and books, Amazon and Netflix seem poised to do away with all vestiges of the real, and enter the digital-only domain. What will be lost in the process is not only the physical reality of books and/or DVDs, but also the fact that many titles won’t make it to Kindle or streaming video, simply because they’re not popular enough. In short, we’ll have the “top ten” classics, and the rest of film history – many superb, remarkable films – will gather dust on the shelf. If you can just click and stream, why wait for the mailman?

Wall Street predictably loved the Netflix announcement, but for those of us who love the medium of film, it’s rather alarming to realize that, in effect, vast sections of film history will now simply cease to exist for the viewer. Adventurous and difficult films will now find it that much harder to find an audience, and mainstream product will dominate the marketplace that much more. Newer films, particularly from developing countries and marginalized social groups, that use streaming technology for distribution will have a better shot at finding an audience, but for the classic films of the past, unless they have a major star or some exploitable link to current events, it’s instant oblivion.

With the switch to streaming video, a whole host or royalty, content, and distribution issues need to be addressed. As Richard Kastelein observed, “In 2010, streamed videos outnumbered DVD rentals for the first time in Netflix’s history . . . But the online move has cost Netflix at least $1.2 billion, according to CNET. That’s the amount Netflix has committed to paying Hollywood studios for the rights to stream their movies and TV shows. And it’s up from $229 million three months ago, the company disclosed in an SEC filing [on October 28, 2010]. Most of that leap comes from a five-year deal that Netflix previously announced with the Epix pay channel, which is thought to be in the $900 million to $1 billion range. But that number could jump again within the next year, when Netflix’s deal with the Starz pay channel expires”3

In addition, there is a plethora of programming designed specifically for the web. Some come and go like mayflies, and die a quick death; others build up a long-term audience, and keep coming back year after year to a cadre of loyal viewers. Web Therapy, for example, has now amassed 46 episodes, with Meryl Streep featured as a recent guest star in a three-episode story arc. Syfy Television (formerly Sci-fi, until the need to copyright the channel’s name forced the somewhat awkward switch to Syfy) has been churning out 10 minute segments of a web serial entitled Riese, with an eye to combining the sections into a two hour TV pilot for the network; and Showtime has oddly created an animated web companion for its hit live action serial killer television show Dexter, entitled Dark Echo, which offers brief (3 to 6 minute) of additional back-story on the series for its numerous devotees4.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DnQWs8o3Vp4[/youtube]

Nor is this number likely to decrease in the future, as analysts from Hudson Square Research Group note that “given that major studios are very likely to expect increasing rates to obtain streaming only rights, we fully expect Netflix’s content costs to rise further”5. Moreover, “Netflix has been aggressively acquiring streaming content.This year alone, it signed licensing deals with NBC Universal, Warner Bros., 20th Century Fox, Epix, Relativity Media and Nu Image/Millennium Films”6. The price for these deals is bound to increase in the future, and this will have to be passed on to consumers.

But Netflix is hardly alone in their quest for digital dominance. As Seitz notes, “Netflix isn’t the only game in town. Besides Redbox, Hulu just launched a premium streaming video service for $7.99 a month. Deep-pocketed companies like Apple, Amazon, Google and Wal-Mart are aiming to take a slice of the market as well.” A side effect of all of this, of course, is that DVD players – even the relatively new, highly touted Blu-Ray players – will become obsolete in an all-streaming world. The industry continues to roll out the hardware, but will the consumer demand be there, even with the added “lure” of 3D? This remains to be seen, and will be something the text examines closely here.

But while the “platform” of film may vanish, for most audiences, the “films” themselves will remain, and audiences, now adjusted to viewing moving images in a variety of different ways, will still want to see their dreams and desires projected on a large screen for the visceral thrill of the spectacle, as well as the communal aspect inherent in any public performance. Film is indeed disappearing, but movies are not. If anything, they are more robust than ever, and are shot in a multiplicity of formats that boggle the mind; analog video, digital video, conventional film, high definition video, on cell phones and pocket-size hard drive fixed focus, auto exposure cameras, and a host of other platforms now just emerging from the workshop of image making.

With more films, videos, television programs, and Internet films being produced now than ever before, and international image boundaries crumbling thanks to the pervasive influence of the world wide web, we will see in the coming years an explosion of voices from around the globe, in a more democratic process which allows a voice to even the most marginalized factions of society.

Stay tuned.

Image Credits:

1. Did Streaming Kill the Video Store?

2. The nightly line-up for the ubiquitous Red Box

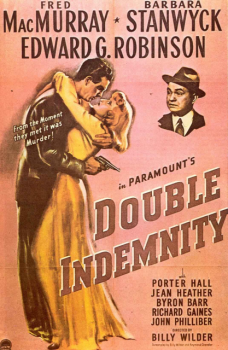

3. The End of Walter Neff?

Please feel free to comment.

- Edwards, Cliff and Sarah Rabil. “Netflix Surges on Streaming-Only Option, DVD Price Increase,” Bloomberg News November 22, 2010. Web. March 12, 2011. [↩]

- Edwards and Rabil [↩]

- Kastelein, Richard. “Netflix Streaming-Only Subscriptions in the Pipeline, But it Will Cost Them,” AppMarket October 29, 2010. Web. March 1, 2011. [↩]

- Hale, Mike. “A Parallel Universe to TV and Movies,” The New York Times, November 12, 2010. Web. February 22, 2011. [↩]

- qtd. in Hayden, Erik. “Netflix Aims to Finish Off the DVD,” The Atlantic Wire, November 23, 2010. Web. March 3, 2011 [↩]

- Seitz, Patrick. “Netflix Hits Record On Streaming Plan, By-Mail Rate Hikes,” Investor’s Business Daily, November 22, 2010. Web. March 12, 2011. [↩]

Wheeler, this is a fantastic opening salvo to your Flow contributions. My area of research has begun to shift towards questions of archives and questions of media fixity or media permanence. Book fans have begun to take notice of the devaluation of the physical artifact. Just the other day, the Internet Archive (my emphasis) began to archive physical books (H/T Boing Boing). When the digital file goes away, the physical copy stored by the Internet Archive may become the only existing item of record for a digitized book.

I’m fortunate to live in a town (Austin) that values film, particularly works that fall outside of the mainstream and languish in obscurity. A city like Austin provides access to several decades of film in various collectors archives, museums, niche video stores and special screenings. For the typical film fan in Oklahoma or Kansas, the options curated by Blockbuster used to be the only option. I share your same lamentation that the audience for film is dwindling due to the demise of the brick and mortar and the rise of the centralized service.

What are your thoughts on the effects of streaming in relation to independent filmmakers and producers?

William — thanks for your kind words. I am deeply involved in completing a new book at the moment, so my comments will have to be very limited. Nevertheless, as to your question, streaming video will certainly make indie filmmakers and producers more available on the web, and in the general marketplace of images, but the problem as always is visibility — distribution. Without a theatrical release, and the attendant publicity, films get lost. So finding a platform is the key issue here — most videos don’t go viral. You need something to stand out.

Wheeler

You might want to read Chris Anderson’s “The Long Tail” or check out Mike Masnick at the Techdirt blog for alternative perspectives on the effects of digital networking on access to cultural goods. I’m surprised that in 2011 the sky is still falling for some folks (e.g., classic films will “cease to exist”).

Once an artifact is digitized, the costs of distributing by networking are lower than putting it on a plastic disc and sending it through the mail. Streaming costs are diving. Netflix (and Amazon) have been pursuing the long tail strategy for years–that is the opposite of “top ten” or blockbuster strategy. The long tail is about exploiting the value of niche goods–goods that small audiences are interested in. Classic films have just as much a chance to find audiences today, if not more so. Their licensing costs are far lower, by the way, than more recent Hollywood fare.

By the way, have you searched for old films on YouTube lately? Stuff I only read about in grad school is there for the viewing!

Please fix the incorrect apostrophe on the second third-person possessive pronoun: Netflix built its business model on delivering DVDs to the doorstep of its’ customers

Please fix the awkward sentence that embeds two sentences directly quoted inside a compound-complex sentence structure to this: Moreover, “Netflix has been aggressively acquiring streaming content. This year alone, it’s signed licensing deals with NBC Universal, Warner Bros., 20th Century Fox, Epix, Relativity Media and Nu Image/Millennium Films.” the price for these deals is bound to increase in the future, and this will have to be passed on to consumers.

Wheeler this is an interesting and complex issue. As a media scholar and filmmaker I cringe at the thought of classics going bye bye. However, I somewhat agree with Cynthia, if we were to add the element of Print On Demand DVD’s. Amazon in particular offers this service. POD is a cheap and “easy” way for big and small studios to make content available without storage. If the digital file exists and someone decides they want to order the DVD, they’re good to go.

For me, storage, waste and manufacturing is where conflict and complexity come in. On one hand, I would love every city to have a hard copy of every book, movie, tv show and radio program of import. On the other, digital downloads and streaming media seems to (the jury is still out) save resources. I’m torn. As for the coming polivocality, it will be a blessing and a curse (as we see with the glut of good, bad and really bad videos available on youtube). Regardless, I’m looking forward to it. Good article.

“Netflix is banking on the fact that most people have no real knowledge of film history, and so they’ll content themselves with streaming only the most recent and popular films.”

This may apply to Redbox, but as Dr. Meyers indicates, Netflix’s current approach is to deemphasize new releases in favor of catalog titles. Hundreds of films that have never been released on video, from major studio films like The Secret of the Incas (1954) to Poverty Row gems like The London Blackout Murders (1943) are now available through Netflix streaming. And the studios’ manufacture-on-demand DVD programs are precursors to making entire studio libraries available via streaming. The Warner Archive program currently offers over 1,000 films and television shows from the WB, RKO, and MGM libraries (in addition to all the films Warners has released on pressed DVDs over the last fifteen years).

If anything, streaming is bringing us closer to the film historian’s utopia of instant access and comprehensive availability. There’s really never been a better time to be a fan of obscure American films. Now, whether today’s audiences are interested in classic cinema is another issue entirely…

Thanks for all your comments! Cynthia, I don’t think the sky is falling. Honestly! At the same point, I am not a fan of digital anything; Facebook, social networking, LinkedIn, iPods, e-mail; you name it. I use these technologies everyday, of course, but they’re cold and lack humanity and warmth.

It’s here, you have to deal with it, but I think that streaming video degrades the entire filmic experience. With the physical demise of the moving image, an intrinsic value is lost, and that streaming videos, no matter how good their quality, can never compete with the theatrical experience. I’ll watch a film on DVD, of course, but nothing competes with the filmic image on a big screen, which is, of course, the dimensions all films up until the advent of television were designed for.

As my late friend Roy Ward Baker once said, “you can INSPECT a film on DVD; but you can’t experience it.” I agree. I’m not “platform agnostic” (to quote A.O. Scott); I want the theatrical experience, with high quality film 35mm film projection, and anything less is, well, less. In addition, with digital formats changing so rapidly, everything is going to have to be transferred to new platforms sooner than later, and to say that “once an artifact is digitized,” as if that’s the end of the process, misses, I think, the point. It’s just the beginning of a long process with no real end in sight. As for watching films on YouTube, you’ve got to be kidding! That would be worse than watching a film late at night on TNT with endless commercials.

Bradley, yes, I’m glad to see these rarer titles available on Netflix, but you have to remember that they’re available now because they’re cheaper, not because of any altruism on Netflix’s part. And again, if you don’t know they’re available, you won’t be looking for them, will you? They’ve got to be advertised as heavily as Lady Gaga to get an audience, and that’s not going to happen. Camille, VOD DVDS are indeed a good option, and I have quite a few, but at roughly $20 a pop, with no extras, and little cleanup, they’re rather expensive. Michael, thanks for the comments.

Obviously, streaming is not celluloid, nor is sitting at home sitting in a nice theatre. For people who fetishize that experience, there will be no alternative.

I’ve been impressed with Netflix’s streaming service, though, which has been, for me, the greatest addition to my movie-watching life since … well, the arrival of Netflix itself. I’ve lived much of my life in rural America, and would never ever want to go back to the days of celluloid-only. Not just because the choices for what to watch were so limited — and, indeed, in rural America were far more limited to studio fare than today — but also, I don’t particularly like sitting in theatres with people who are chewing, whispering, texting, talking, and am much happier to watch a film on the big flat-screen tv at home, with friends or family or alone. Sitting in a theatre with a bunch of strangers is, certainly, a social experience, but so is watching with friends or family or neighbors or somebody who just happens to be staring in your window. And watching a movie alone can be a marvelous and intense experience as well.

Netflix is, of course, a business in a capitalist country, so they’re going to do whatever they can to make their profits huge, but the addition of so many films to their streaming service that are otherwise unavailable has been a real boon, and it is not at all a contradiction to a successful business model — indeed, a successful business model will want to acquire as many titles as possible, because that ensures that as many people of as many different tastes will remain subscribers.

So they’re not purely altruistic; so what? “[I]f you don’t know they’re available, you won’t be looking for them, will you? They’ve got to be advertised as heavily as Lady Gaga to get an audience, and that’s not going to happen” is really missing a lot of the point — yes, certainly, obscure films aren’t going to suddenly get a million viewers. They never were in the first place. But they will will be available, and that’s the important point — and through Netflix’s recommendation algorithm and update services such as the RSS feed for all new streaming releases, it’s easy enough to know a lot of what’s there. It’s also fun to stumble on things.

These are all point that this essay seems to miss, because the author seems so stuck on an antiquated view of both business and technology. (His hatred of all digital technology is pretty telling, and I hope he knows that the “coldness” of technology is not universally perceived.) I’ll be curious to see what sort of book results from such misunderstandings of the current environment.

It’s true, though, that Netflix is not a service that allows us to project actual film in theatres.

Gee, Matthew. Guess you don’t really like film all that much, do you? “I don’t particularly like sitting in theaters with people who are chewing, whispering, texting, talking, and am much happier to watch a film on the big flat-screen tv at home, with friends or family or alone.” What a nightmare! Who would want to experience a film with other people? A large crowd of strangers? Gosh, what a terrible idea.

I’m sure that you’ll do just fine with a cellphone image. And I think that you miss the point, really — in the digital era of everything being available, most people will never hear of the lesser known titles, because the publicity machine will blot out all but the immediate present. And far from having a “hatred” of digital technology, I embrace it; I have about 10,000 DVDs to prove it, and watch them all the time. But I recognize the format for what it is. It isn’t the authentic experience; it’s a mediation.

I’m certainly not fetishizing the the theatrical experience; but, just for a moment, can you imagine watching a DVD of a production of Wagner’s Ring cycle,for example? Do you think it would communicate 1/10th the power it does on stage? The Met, and other opera companies, have long been streaming their performances to theaters around the United States, but what you get is merely live television of the dullest nature; master shots, close ups, and that’s about it. No, there’s a barrier there, and not to acknowledge it is again, to miss one of the points of my essay.

Similarly, with DVDs and streaming, you get a simulacrum of the experience. You don’t get the experience itself.

As for “Netflix’s recommendation algorithm and update services such as the RSS feed for all new streaming releases,” please. I have yet to receive a useful suggestion from this source, or from Amazon’s recommendation mechanism, either. Did you ever hear of the term “digital cleansing?” Every so often, it’s good to take a nice step back from the computer, and see what the real thing is like. In a theater. On a screen. With lots and lots of other people.

Interesting discussion! At first I was frustrated with Netflix’s putative move to “all streaming” because, really, they have not streamed many of their titles. For example, of the 367 disks currently in my queue (this does not include “saved” disks with availability that is “unknown”–which is generally how Netflix indicates that it simply has not acquired a title that is available), 90 are streamed. For a few months, however, I did enjoy watching certain titles on my laptop–particularly recent TV shows, which were originally created with the idea that they would be streamed. Then I purchased a large plasma TV from which I could watch Netflix titles streamed. I found that, blown up to 50 inches, many titles looked like absolute crap, though, still, many recent TV programs shot on high-def video were fine. Quality of films varied widely, with some poorly masked, many containing very poor quality blacks and grays, and the image generally better than VHS but not as good as DVD, and certainly not as good as Blu-ray. (For a great example of a deeply disappointing streaming experience, see Netflix’s streamed version of The Third Man.) Then DVD titles started to disappear from my queue as they became “streaming only.” This means that Netflix is increasingly not allowing me to watch reasonable quality (if far from 35mm quality) versions of films. So my frustration has started to shift from “not enough films are streamed” to “too many films are streamed only.” I briefly paid Netflix extra for Blu-ray, only to find that I could watch new releases on Blu-ray, and a few classics, but little else. While one-quarter of the items in my queue are available via streaming, only 10% are available on Blu-ray.

This probably all sounds like a bit of a rant, but what I am pointing to are some of the real practical difficulties of “acquiring content” at home (or elsewhere) rather than watching films in a theater. I love watching theatrically, and would not describe myself as platform agnostic. At the same time, I am receptive to other platforms, and I particularly enjoy watching Blu-rays on a plasma TV, or projecting disks onto a large pull-down screen. Of all the different ways of enjoying film, TV, and other kinds of media (e.g. entertainment never designed to appear on TV, like Dr. Horrible’s Sing-Along Blog), it is streaming that has consistently been most disappointing to me. It is really neat when you can find clips from obscure films on YouTube, but such clips are often pixillated. Even if they are not pixillated, when you blow them up to fill your computer screen, they go a bit blurry. In other words, we’ve gone digital, only to find that much of our viewing is of equal or lesser quality than VHS was. I use YouTube frequently as a research tool, to check a quotation, for example, but I rarely feel that I have actually “watched” something on YouTube because the sound and image are not satisfying. One obvious exception is content created at low-resolution, specifically for online viewing–see, for example, Guy Maddin’s Nude Caboose (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z3l09oxeYTE).

People often state as a fait accompli that DVD and Blu-ray are dying, short-lived, etc. Given the number of cinephiles interested in aesthetically gratifying viewing experiences, and the fact that increased availability of titles via Netflix, especially in the DVD-only days, has only fostered that diverse community of viewers, I believe that DVDs and Blu-rays will soldier on, simply because many cinephiles (or videophiles, if you will) are turned off by the insufficiencies of streamed images and are willing to buy DVDs and Blu-rays. DVD and Blu-ray will in effect become a “boutique market,” since so many people are comfortable with a lesser audiovisual experience. That said, DVD and Blu-ray are far from perfect, and I am not the first to lament that some Blu-rays have been created so as to remove the grain of the film completely, so much so that certain titles look like they were shot on video.

Access to large numbers of titles is great, and I would never want to go back to the pre-home-video days, when you were completely at the mercy of late night TV schedulers if you did not live in a big city with a lively revival theater circuit. At the same time, streaming is often a deeply dissatisfying experience.

Indeed, Heather.

As you note, “I purchased a large plasma TV from which I could watch Netflix titles streamed. I found that, blown up to 50 inches, many [streamed] titles looked like absolute crap, though, still, many recent TV programs shot on high-def video were fine. Quality of films varied widely, with some poorly masked, many containing very poor quality blacks and grays, and the image generally better than VHS but not as good as DVD, and certainly not as good as Blu-ray. (For a great example of a deeply disappointing streaming experience, see Netflix’s streamed version of The Third Man.)”

And more ominously, “then DVD titles started to disappear from my queue as they became “streaming only.” This means that Netflix is increasingly not allowing me to watch reasonable quality (if far from 35mm quality) versions of films. So my frustration has started to shift from “not enough films are streamed” to “too many films are streamed only.” I briefly paid Netflix extra for Blu-ray, only to find that I could watch new releases on Blu-ray, and a few classics, but little else. While one-quarter of the items in my queue are available via streaming, only 10% are available on Blu-ray.”

This is why, since we don’t live in the best of all possible worlds, I buy as many DVDs as I can, because once they go streaming, they don’t come back. Many DVDs are on the market for a matter of months before they go out of print — permanently. If course, you also miss the notes, the extras, etc. when a film goes streaming only.

I wish, I really wish I could agree with you, Heather, that DVDs will “soldier on” in a streaming world, but all you have to do is look at Amazon’s book sales section, and you’ll see that many titles are no longer available in print, but only in Kindle.

What can I say: I like books. You know, with no batteries, screens, with print on the page. The kind you can loan, Xerox, mark up, put bookmarks in, and all of that.

The good side of this is that when you can get hardcover copies of many books on Amazon, often first editions, they’re going for pennies, plus shipping. The downside is that when they’re gone, it’ll be Kindle only. So I buy as many hardcover books as I can, and I find them very useful. It’s the same with DVDs; I buy as many as I can, because all too often, when I look for a title I’ve wanted, but passed over, suddenly it’s gone. I’m afraid this is the future of the moving image.

I don’t live in a major metropolis either, although we do have an excellent art house here, the Mary Riepma Ross Film Theatre, and in Omaha, Film Streams. I love the convenience of DVDs, but as I say, it’s not the same as 35mm. And as you note, Heather, streaming quality is highly variable.

So, in this real world we live in, I say stock up on as many DVDs as you can — now. They may not be a permanent platform, but they’re better than an all-streaming world, in which people who don’t really care about films, but rather only about the bottom line, offer us only one option.

Thanks for your comments, Wheeler. Of course, you are totally correct that once things go out of print, they are gone, and you can forget about high-quality home access. As professors, this will eventually put us in a bind, insofar as Netflix and other streaming services tell us that we can’t use streamed content for any use other than personal. (Despite the FBI warning at the beginning of DVDs, they ARE legal for classroom use.) So how do we teach without DVDs? Certainly, in the future schools will have to work out some kind of contracts for streaming use in classrooms–which one can imagine could be prohibitively expensive–or they will simply have to look the other way and expect us to break the law.

In any case, I said I thought DVD and Blu-ray would persist because there is a “boutique market” for them. Criterion has been slowly but surely growing its Blu-ray list, while continuing to release new titles on DVD as well. So what I see for the future is continued release of films as objects to home consumers who want a high-quality product (and who want interviews, etc.–the lack of extras for streamed Netflix films is a huge flaw for many cinephile consumers), but outside of specialty lines like Criterion, the number of new titles actually available for sale will shrink. Mercifully, some studios have been doing a good job at burning disks on demand, as I believe you mention in your original post. While it is expensive for studios to do a full release of a picture on DVD, on-demand is cost-efficient, which may well ensure its future.

Wheeler and Heather,

In my view we are indeed facing the death of film culture. As you note, Wheeler, many films have yet to be released on home video (think many of the prewar films of Max Ophuls), and will face increased resistance not only from Netflix and their ilk but the Blu-ray transition. Film as an art form has always been treated with marginal seriousness in the U.S., and business demands have eroded what seriousness existed. To my eyes, streaming video is an abomination. We can hope that Criterion, Kino, and these MOD archives will soldier on, but the data do not offer many consolations.

Dear Chris and Heather:

Thanks both. Forecasting the death of film culture is too apocalyptic even for me, Chris. I feel that film will always be with us, and that boutique DVDs will be with us certainly for the immediate future. Heather, the issue of streaming use in the classroom is vitally important; I wasn’t aware of this.

I would, however, point to CDs as yet another example of the trend towards streaming only content. Does anyone buy CDs anymore? No, they buy individual song downloads from Amazon or iTunes, so no matter who provides the content, there are only two major outlets. Streaming audio has solid sound quality for the average listening, but serious audiophiles continue to wish for a better quality signal, and are dissatisfied with digital downloads.

I guess my major concern is that since Netflix and its allies are so bottom line driven, they won’t care if the quality of the image is terrible, just so long as they make money. Most customers won’t mind poor quality in older titles, because they won’t notice it, or rent the films in the first place because they’re only interested in current hits. But despite all this, I’m not ready to throw in the towel. I just wish that streaming video had higher quality, and that a Criterion streaming service, for example, would emerge, with the highest possible technical standards.

I think Mr. Dixon’s main point is a potent one, the accessibility based on what rights survive, are available and considered to be “worth” pursuing and continue to pass hand to hand. Indeed we have already seen many films fall off Netflix’s catalog, first from the physical discs and then the streaming options.

Every time we move to a new format/medium we lose 25 – 66% of what was available before. Many titles on VHS never made the shift to DVD, and many titles on DVD/Blu-ray will never make it to streaming. New content will replace the lower-selling titles and those with confused or unknown rights/provenance.

In a future without physical media (either consumer or production masters) archiving will be a major issue. POD discs have a lifespan of 5 years. That will not ensure long life for many of these unknown titles.

Fascinating discussion of the issues of access (which is increasing through services like Netflix and YouTube) versus quality (which is decreasing via digital compression, etc.). We may have different views of which is more significant: the loss of filmic quality or the gain of easier access. As someone who values technical quality too (and have stormed out of movie theaters because of poor projection!), I certainly share the sense of loss expressed here. But my views have evolved. If forced to choose, I have come to value access over quality. Why? Because the significance and persistence of a cultural artifact, such as a film, depends more on its reaching an audience than on its technical quality.

Consider the generation of viewers whose primary exposure to pre-1948 film was on independent broadcast TV stations in the 1960s-70s: terrible resolution, cut up with commercials, entire scenes chopped. Horrible. But did that prevent those viewers from connecting to, enjoying, and persisting in watching those films? I’d argue it’s possible that their dissemination on a technologically inferior platform helped sustain interest and popular memory of those films (Wizard of Oz, anyone?). People today roaming YouTube may make similar discoveries.

So while it is true that many cultural artifacts will disappear during this vast digital transition, we, the audience, have more tools at hand today than we had before to prevent those disappearances. And that, I believe, is the key.

In Lost in the Fifties, Wheeler Dixon wrote about all the movies that have already disappeared for all intents and purposes. He definitely knows of what he speaks. His article should serve as a wake-up call to all of us who care so we can, as a first step, create an “endangered species” list of movies to save.

Surely there is a foundation or two out there willing to underwrite this process?

Streaming is the next big thing on Web.In fact all the IPL 4 matches were streamed via Youtube and it was a great success.In future people will watch movies on Online Streaming Store.No body will rent or buy DVD’s two years down the line.

Pingback: Daily Links from the Selectism Staff | Selectism.com

Pingback: Selectism | Around the Web | Ashton Kusher

Pingback: THE ARCHIVIST’S MANIFESTO | HALF/FILMS

Pingback: How Long Will it Last, and Do You Really Own It? Wheeler Winston Dixon / The University of Nebraska, Lincoln | Flow