Spoilers at the Digital Utopia Party: The WGA and Students Now

The easy availability of desktop video production coupled with distribution through YouTube and Facebook has increased the ranks of students aspiring to be Hollywood directors. Enrollments in production courses and applications for film school are booming: at the USC School of Cinematic Arts about twenty-four applicants vie for each undergraduate place in production every fall. Most of them want to direct, rather than work in media in any other capacity; and most of them want to work in film, not TV. In truth, it is far more likely that they will end up working in television, not film, and in some role other than writer/director.

Of course, for decades the young have headed to Hollywood with dreams of making it. For this reason alone, it is astonishing that creative workers in film/TV enjoy collective bargaining and union representation, when union membership nationwide is at an all-time low and white collar professionals in all lines of work are an extremely difficult group to organize. The issue in the WGA strike revolves around compensation for work distributed online—which implicates the young in two important ways. First of all, the generation currently in film school eagerly gives their work away for free in hopes of being discovered. Student complaints at all the major film schools—where copyright for creative work produced in classes is held by the school, not the student—center on restrictions about posting creative work online. Second, students are accustomed to using the Internet for entertainment to such an extent that no one is sure they will miss (especially network) television if it goes away. As one showrunner put it “Kids today, you take TV away, they’ll say, ‘Big deal,’ and they’ll click on the computer.”1

It should come as no surprise that Hollywood’s creative labor strikes have occurred at critical moments of technological change within the industry. Once every generation, enough technological shifts happen within the industry that the old systems of compensation for labor need to readjust to keep pace. Just looking at the WGA strikes since the inception of television makes this clear. In 1960, television writers went to the picket lines and established the residual system that has since ensured that television writers would see a profit from the rerun. In 1988, the WGA failed in their attempt to secure fair residuals from the sales of film and television on VHS. In part, what led to the WGA giving up their fight was that television writers saw no reason to care about VHS residuals—at the time they could not imagine the future success of TV DVD sales. Now, in this latest technological cycle, the WGA is hoping to make up for what they lost in 1988. Though during the last strike screenwriters were the most vocal about their concerns about new technology, this time around it is television writers that are not only the first to be affected by the strike, but also the more critical players right now in discussions regarding digital compensation.

Calculating appropriate compensation amid the proliferation of new media outlets is far trickier than the math put forth by studio heads to the investors and the press about the booming financial success of their digital platforms. Entertainment attorney Jonathan Handel recently crunched the numbers in, “Reflections on Residuals,” but divining the future of digital entertainment—let alone calculating the bottom line on present-day media—is a complicated task.2 Marc Andreessen, founder of Netscape, suggested in his blog that writers turn to the Silicon Valley model: talent attracts venture capital, artists shares ownership with venture capital shareholders, everyone makes a fortune, and the quality of the media created is better than before. In this scenario, unions are an inconvenient feature of an anachronistic system where talent must band together and “engage in adversarial collective bargaining to try to extract a share of the ongoing economics of their output.”3 Presumably the adversarial nature of labor management relations vanished in Silicon Valley, when all “talent” became “owners.” In the Los Angeles Times, Patrick Goldstein criticized the WGA for not understanding that classic union organizing no longer works in the digital age:

“The WGA is fighting the good fight. But the glory days of Norma Rae are gone. Real change in today’s world comes from the energy and ideas of entrepreneurs, not from labor negotiations. To take control of their work, writers have to cut out the middleman.”4

Andrew Ross’s study of creative workers in new media, No Collar, has elucidated how risky, hyper-competitive, and ultimately exploitative working conditions are under the model of “entrepreneurial labor” common to Internet start-ups and advertising firms specializing in the online environment.5 The brutal workday at video game leaders like Electronic Arts is also receiving some publicity, and it is likely that unionizing efforts will be directed there.6 The young and the ambitious in the world of Web 2.0 do not need old-fashioned things like collective bargaining and unions—they will just slow you down.

Digital utopianism threatens decades of union struggles by film/TV practitioners who have fought the endless lines of eager young people (especially those with parents who can support them indefinitely) who are willing to do anything to make it.7 The WGA radically threatens the cybertarian view of new media that has dominated the discourse of DIY, user-generated content, blogging and all things Web 2.0., by pointing out that all this media production for the Internet is unremunerated—all the videos, photos, and blogs posted on the web (and thereafter the property of the website owners). Of course, Silicon Valley could learn a thing or two from the WGA. Jaron Lanier argued in an editorial for the New York Times, “Pay Me For My Content,” that designing the Internet so that content is always free was a mistake. A computer scientist, Lanier has defected from the “Internet idealist” position because, he argues, business opportunities for writers and artists have decreased and “the only business plan in sight is ever more advertising. One might ask what will be left to advertise once everyone is aggregated.”8 Lanier plainly critiqued the YouTube model in December 2006: “The Web 2.0 notion is that an entrepreneur comes up with some scheme that attracts huge numbers of people to participate in an activity online….What is amazing about this idea is that the people are the value—and they also pay for the value they provide instead of being paid for it.”9 Maybe giving it away isn’t such a good idea after all. It brings the concerns of the middle aged, health insurance, mortgages, etc., to spoil the party of convergence media as a dazzling route to self-expression unfettered by material or economic constraints.

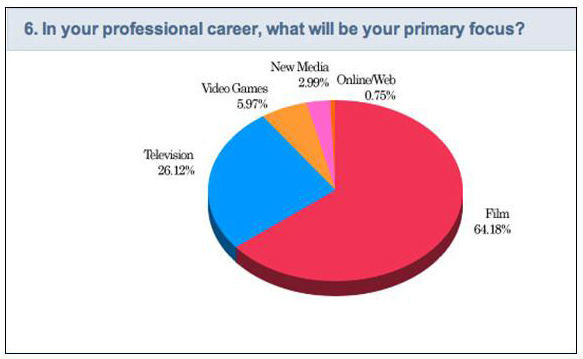

To investigate the extent to which the “entrepreneurial labor” model of the Internet has been embraced by film students, we conducted a pilot survey to assess how Los Angeles film students picture their future careers in Hollywood and the desirability of professional unions.10 The WGA strike provides an occasion to assess what young aspirants to these industries understand about labor and how much digital utopianism influences their career plans and willingness to work for free. Our preliminary research has shown that while students learn about their craft in film school, there is little explicit teaching about labor struggles for creative workers or the history of the labor movement in Hollywood. Ninety percent of the students surveyed stated that they know “little” about the entertainment guilds, even though 87% of them plan to join one of them during their career.

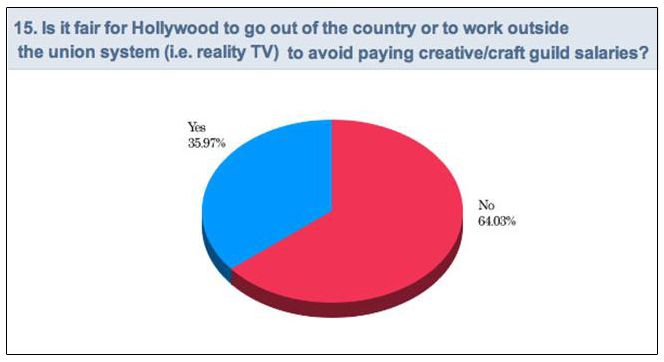

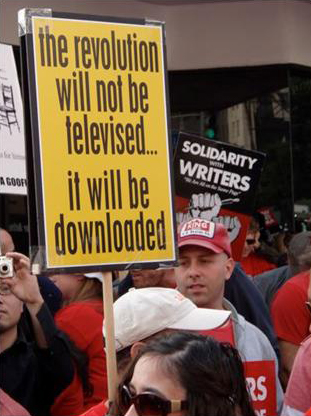

We found that the older students are more likely than their younger classmates to understand the role the guilds will play in their professional careers—and that those who plan to work in television generally think more favorably towards the labor guilds. While only 24% of the entire group surveyed believed that joining a guild was “very important,” the numbers increased dramatically among older students. Of students aged twenty-three and older, 48% say unions are “very important,” and the numbers increase to 60% for students twenty-six and older. As a whole, 64% of students thought that it was unfair for Hollywood to go out of the country or to work outside the union system to avoid paying guild salaries. But for students who plan to enter television, those numbers were even higher (85%). Those student who were interested in becoming directors were the more likely to say it is fair for studios to circumvent unions in order to keep their costs low. The stakes of the strike are high—not just for industry practitioners but for aspirants, as well. At a recent rally on Hollywood Blvd, one WGA picket sign read: “The revolution will not be televised, it will be downloaded.” It is incumbent upon media scholars and teachers to support the WGA by helping students understand the history and urgency of the strikers’ demands to all creative workers who want to survive this digital revolution.

Image Credits:

All photos by Miranda Banks.

Graphs by Ellen Seiter.

Please feel free to comment.

- Greg Garcia, writer and creator of My Name is Earl. Neely Tucker, “Reality Looms: Writers’ Strike Could Change Pace of Television,” The Washington Post (1 November 2007). [↩]

- Jonathan Handel, “Reflections on Residuals: Go Forth and Multiply,” The Huffington Post (23 November 2007). [↩]

- Marc Andreessen, “Rebuilding Hollywood in Silicon Valley’s Image,” blog.pmarca.com (12 November 2007). See also Marc Andreessen, “Suicide by Strike,” blog.pmarca.com (4 November 2007). [↩]

- Patrick Goldstein, “Come on, writers, script your futures,” Los Angeles Times (20 November 2007). [↩]

- Andrew Ross, No-Collar: The Humane Workplace and Its Hidden Costs (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2004). See also Gina Neff, Elizabeth Wissinger & Sharon Zukin, “Entrepreneurial Labor among Cultural Producers: ‘Cool’ Jobs in ‘Hot Industries,” Social Semiotics, 15 (2005): 307-334. [↩]

- Toby Miller, “Anyone For Games? Via the New International Division of Cultural Labor?” forthcoming. [↩]

- David Hesmondhalgh, “Television, Film and Creative Labor,” Flow v.7. [↩]

- Jaron Lanier, “Pay Me for My Content,” The New York Times (20 November 2007). [↩]

- Jaron Lanier, “Beware the Online Collective,” Edge 12/25/2006. Lanier’s unusual position among computer scientists is compatible with his work for Linden Labs (Second Life), which has a stake in promoting ways to monetize content. [↩]

- This survey, “Career Plans in the Media Industries,” asked University of Southern California School of Cinematic Arts students to answer a series of question regarding how they see their future careers in the film and television industry. 139 undergraduate and graduate students’ responses were collected using an on-line survey tool. [↩]

I was fascinated by how Seiter and Banks approached the WGA strike. Though many people and scholars have covered the strike, there is has been little attention focused on the far-reaching effects of the strike in relation to production students and their goals. In thinking of television shows and new media, one show that has been touted as the example of the WGA strike is Gossip Girl, the latest teen drama from the CW. Though the show has performed poorly in terms of Neilsen ratings, a large percentage of viewers watch episodes online. I’m wondering as more and more shows begin to offer episodes online, how much online viewing will affect shows’ ratings, particularly in relation to shows canceled or picked up based on audience numbers.

If you’re interested in keeping up with the WGA strike as it’s happening, please check out: http://unitedhollywood.blogspot.com/.

Also, I’d like to note that the University of Texas, which is a major film school, does not hold the copyright for students’ work produced in the Radio-TV-Film Department. Students retain the rights to their films. This has its own complications, but does avoid the complication mentioned by the authors above; students may post or screen their work at their discretion, within the parameters of rights clearances, but with no restrictions by the university.

This was an interesting and well written piece!

But as someone who is interested in copyright, intellectual property, and fair use (as it is used, or not), I am interested in the issue of who holds copyright on work produced by students in production classes.

The authors of the article seem to say that major film schools lay claim to holding those copyrights, but Jean Lauer says that isn’t true for UT-Austin.

Can someone help clarify this issue for me as to the policy at other schools (whether well known film schools or not)?