Camera Looks, Laugh Tracks, and TV Comedy

Michael Z. Newman / University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

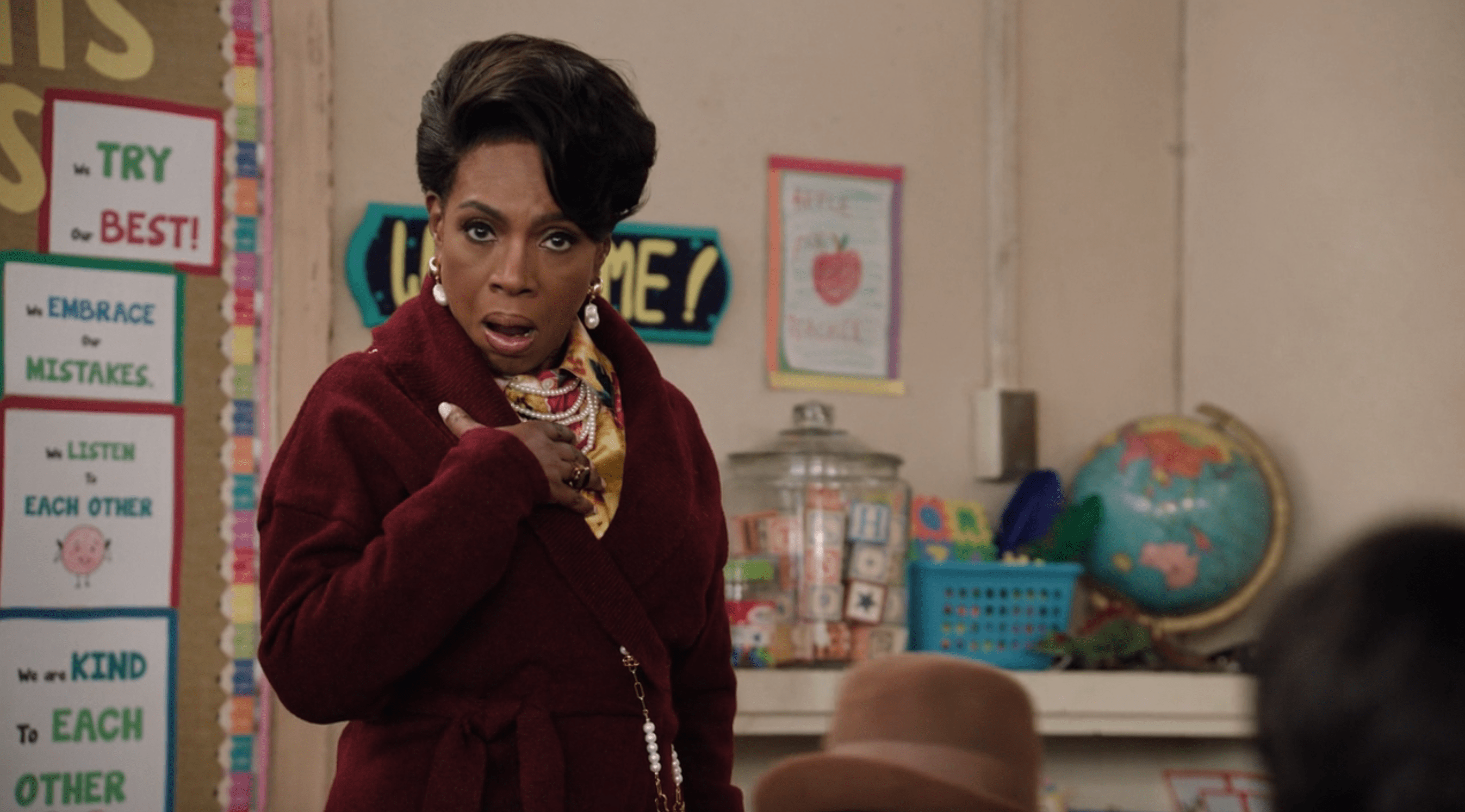

Among many of the appeals of Abbott Elementary, so far the standout US network sitcom of this decade, are its characters’ regular camera looks. They draw us in and invite our participation, accentuating the comedy captured, according to the mockumentary premise, by a fictional crew. Rewatching the recent episode “100th Day of School” (26 February), I noted twenty-one of these looks spread across the episode, an average of one a minute, and sometimes several in a single scene (figure 2). Most of the show’s main cast gets these moments, as does one of the kids in Jacob’s 6th grade class. Barbara (Sheryl Lee Ralph) is central to this episode’s plot as she learns she is going to become a grandmother and freaks out about feeling (being) old. Barbara gets seven camera looks expressing a range of reactions to the situations of her arc: discomfort, amusement, shock, irritation, satisfaction. In one scene, she glances into the lens four times, making four different faces. The camera looks in these contexts show us only one pair of eyes, but they are never solo acts. They arise from a beat of the story in relation to the other characters. They signal feelings and cue our reception. As the show’s editors have said, they often punctuate and underline moments, effectively saying “can you believe this?”

This technique of regularly punctuating TV (or movie) storytelling with moments of acknowledging the audience is both novel and familiar: a somewhat recent addition to the menu of standard sitcom devices, and a long-practiced way of establishing connections between screen performers and their public. My purpose here is to subject this old/new convention to a little bit of critical defamiliarization.

Since the successful run of The Office on NBC, which began 20 years ago, the mockumentary style of single-camera comedy has been a fixture of TV offerings, and by the time Abbott arrived in 2021, it was regarded by one influential critic as a fresh take on a format that had descended into cliché. Whether a documentary filming scenario is written into the plot to motivate the camerawork and storytelling or not, this style recalls cinema vérité conventions of cinematography, perpetually reframing and zooming. It also invokes more contemporary documentary conventions of on-screen interviews with characters addressing the viewer, often glancing just beside the camera lens, as if to an implied interviewer. But the camera looks I’m interested in occur during the observational scenes rather than confessionals. Tim on the British version of The Office and his American cousin Jim are key camera lookers, silently reacting to the antics of their bosses or coworkers, but so many other compelling glancers have emerged since then including Ben on Parks and Recreation and Guillermo on What We Do in the Shadows. Perhaps some documentaries in the vérité or direct cinema style contain such conspiratorial glances caught by kinetic cameras, but they are now much more centrally a scripted comedy convention. Fictional characters look at us routinely, multiple times an episode, as a new form of sitcom shtick growing as familiar as a favorite actor’s entrance through the front door or a signature catchphrase.

Directly addressing the camera might be regarded as taboo in most genres, but Hollywood films and network TV shows have incorporated occasional camera looks all along and motivated them in varied ways. Sitcoms like Gilligan’s Island and Three’s Company authorize particular characters (Skipper and Mr. Roper, respectively) to offer these glances. The protagonist of The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis addresses the audience directly in asides shot before a Rodin Thinker sculpture, which adds visuals to the kind of voice-over narration that gives a first-person perspective to later TV comedies like Sex and the City and Everybody Hates Chris. Clarissa Explains It All turns this technique into a kind of parody newscast with “Clarissa Update” segments. Malcolm in the Middle and Fleabag are comedies with regular asides that offer these monologues in the middle of unfolding scenes. Fleabag even chats with us in the middle of having sex, which is pretty cringe. In none of these examples is there a diegetic premise of a documentary production to motivate the looks. Movie characters do this too, e.g., in Tom Jones and Alfie.

The film tradition known as comedian comedy makes this kind of “extrafictional” direct address one of its basic techniques.[1] Drawing on a vaudeville aesthetic of affective immediacy and emotional impact, comedians from the silent era clowns like Charlie Chaplin through the Marx Brothers, Bob Hope, and Jerry Lewis look at the camera in moments of diegetic rupture (figure 3). Frank Tashlin was known for this device in both his animated and live action films.[2] Mel Brooks’s spoofs are often audience-aware, as when Young Frankenstein’s monster, preparing to greet his bride in bed at the film’s denouement, looks at us knowingly over his reading glasses. Woody Allen’s narration in Annie Hall, addressing the camera during several of the film’s scenes to discuss his life with us, the assembled moviegoers, picks up where Groucho and Hope left off.

Periodically stepping out of the frame of dramatic representation to establish a direct rapport between performer and spectator works because this kind of comedy is about establishing that the comedian and the audience are part of one space, that they are joined in the communal experience of entertainment. The most prolific camera-lookers of this tradition were probably Laurel and Hardy, vaudevillians who transitioned from the variety stage to silent and then sound filmmaking. Oliver “Babe” Hardy was particularly notable for his regular glances at the camera, i.e., at the audience, conveying exasperation or disbelief, or whatever reaction is warranted from the comical situation (figure 4). Charles Barr sorts these looks into a range of expressions that will sound familiar to mockumentary sitcom viewers: exasperated, quizzical, apprehensive, conspiratorial, and embarrassed.[3] Babe Hardy and Jim Halpert are cousins united across the decades by their performance of reactions for us, the viewers.

Comedy is one key genre for this appeal to the camera/audience, but musicals also incorporate this device routinely and from a similar place of bringing stage conventions to screen arts. Some of these looks are similar to comedian comedy asides, which makes sense considering that “musical” was originally short for “musical comedy.” Maurice Chevalier’s lascivious looks are in this vein, and it’s not hard to imagine his characters doing the same kind of direct address as in One Hour With You or Gigi from the lip of a stage. Topol’s camera looks in Fiddler on the Roof, adapting the storytelling role of the Broadway original, marry comedian comedy and the first-person narration of the Sholem Aleichem short stories from which the musical was adapted. But we also get camera looks when singers deliver their songs directly to us, as in “We’re In the Money” from Gold Diggers of 1933 (figure 5) and the “Broadway Melody” sequence of Singin’ in the Rain. Again, the stage musical tradition authorizes this style of singing to a crowd, and the performers (in these examples, Ginger Rogers and Gene Kelly) had been Broadway stars en route to becoming movie stars. Comedies and musicals are genres in which the direct appeal to an audience is conventionalized to the point that looking at the camera just makes more sense than avoiding looking at the camera. Stage performance conventions run concurrently with the emergence of screen entertainment in the first decades of the twentieth century. Comedians and singers address the audience, whether on a theater stage or a movie soundstage.

There are many other kinds of camera looks. Point-of-view editing motivates some looks, as in several Hitchcock films. A look at the camera can provide emphasis or flourish, juicing a reaction and giving the audience a little jolt, as happens in the Jaws scene in which Hooper discovers a shark victim underwater and expresses his shock directly at the lens. The look at the camera can also mark a moment when characters step outside of the storytelling situation to comment or reflexively acknowledge the artifice of drama. This is done in a comedic register when it’s Groucho Marx or Bob Hope, or when Ferris Bueller urges us to go home at the end of the credits, but has a different tenor in Fight Club’s direct address segment.

The discourse these days invariably labels all such moments “breaking the fourth wall,” and YouTube and other user-generated content outlets are a bottomless source of roundups of the greatest moments when movies, TV shows, and video games violated this standard of decorum. Practically any look at the camera during a scripted/fictional screen representation is now sorted under “fourth wall,” which makes it super easy to find all kinds of examples. (This montage is particularly well done.) My students all seem to know this bit of modernist theaterspeak. But it’s a relatively recent thing to call all camera looks “breaking the fourth wall” – many sources of pre-internet criticism that cover this topic don’t use that phrase. Entire books were written about Laurel and Hardy that make no mention of walls.[4] Steven Cohan’s book chapter on the Hope/Crosby “road” movies catalogues their numerous self-reflexive devices without mentioning the fourth wall.[5] The most cited essay on the topic of camera looks is Marc Vernet’s “The Look at the Camera” from 1989.[6] Again, no walls.

The premise of naturalist drama being constituted out of an illusion of private scenes performed in public spaces gives us “fourth wall” logic, which is also central to classical narration in film and television. But the conventions of dramatic naturalism are in a relationship of friction and unease with those of much comedy, in which performers are expected to establish a rapport with an audience that leads to amusement and laughter. And some kinds of comedic live performance, like vaudeville and later standup, are premised on direct address. If vaudeville even had a fourth wall, according to one of its recent historians, it was among its basic premises that this wall be regularly penetrated by performers who “set out to engage, terrify, or startle” the people in the audience.[7] The origins of sitcoms are in vaudevillian performances like The Jack Benny Show that mixed direct address and dramatic scenes (on radio and then TV).[8] Comedian comedy in movies and television sitcoms have a common ancestor in variety stage traditions.

The sitcom studio audience with its audible laughter that is so central to the aesthetic of multi-camera shows from the 1950s onward retained some of the elements of stage comedy while dispensing for the most part with direct address, despite the occasional song or dance number snuck into programs like The Dick Van Dyke Show (and much more recently, Mid-Century Modern). But the audible audience, or the recorded simulation of one, maintained a sense of communal experience. Derided as “canned laughter” for its whole history, this sitcom convention would pop out more as a tired, old trope once single-camera comedies arose to challenge the old style in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

The durability of the mockumentary sitcom – despite the waning of a cartoony post-Simpsons single-camera style epitomized by Scrubs and 30 Rock – might seem like the ultimate rejection of the proscenium/laugh track multi-camera aesthetic. The point I’ve been working up to here is that the celebrated, fourth-wall-breaking sitcom camera look functions in a similar way as the vaudevillian audible audience, that most recognizable and often unwelcome element of the classic sitcom style.

Weakly motivated as a glance at the crew, the stronger motivation for these camera looks is as establishing a connection to the viewer. The diegetic documentary is a flimsy pretext of questionable relevance.[9] Abbott Elementary is supposedly constituted out of footage being shot for a documentary about public education. As LaToya Ferguson regularly notes in reviews for Episodic Medium, this long ago ceased to be a credible premise. Beginning with the pilot, the camera crew has gone places where it should never be going, such as following children into the restroom in the pilot episode scene where Gregory and Janine first meet-not-cute. These offscreen documentary filmmakers have followed the characters to bars at night, shown up at Janine’s apartment on Christmas Eve, and set up at an airport hotel conference room where Ava sidehustles as a motivational speaker. The power of the mockumentary sitcom today is not its self-reflexive satire of documentary pretensions, if it even ever was. The jerky camera and confessionals are so conventionalized that no one can be buying these shows as pastiches anymore. The style is effective because it affords verisimilitude, direct address, and comical emphasis.

The laugh track and the camera look function in much the same way. According to one Laurel and Hardy critic, the camera look also functioned for them as a prompt to laughter, with the look affording a pause for the audience to react. The filmmakers, by this account, clocked audience laughs during preview screenings to determine how long to hold the shot of the look.[10] However much it’s understood in relation to the mockumentary frame, the camera look in a show like Abbott places the viewer into a relationship with the performance and performer, reestablishing a community of co-presence that film and television drained away from comedic performance mediated by cameras and screens. The camera look is an indication of comedic intent and gives us a nudge to see and feel the moment as the characters do. It also retains a trace of fun transgressiveness that is antithetical to the predictability and banality of the laugh track, but this serves to hide the common appeal of both devices, which is to bring us into an imagined space of contact with the comedian and guarantee our pleasure.

Image Credits:

- Sheryl Lee Ralph as Barb in Abbott Elementary. (author’s screen grab)

- The 21 camera looks in the Abbott Elementary episode “The 100th Day of School.” (author’s screen grab)

- Groucho Marx in Duck Soup. (author’s screen grab)

- Oliver Hardy in The Fixer Uppers. (author’s screen grab)

- Ginger Rogers in Gold Diggers of 1933. (author’s screen grab)

- Steve Seidman, “Performance, Enunciation and Self-Reference in Hollywood Comedian Comedy,” in Hollywood Comedians, The Film Reader ed. Frank Krutnik (Routledge, 2003), 21-41. [↩]

- Ethan de Seife, Tashlinesque: The Hollywood Comedies of Frank Tashlin (Wesleyan UP, 2012). [↩]

- Charles Barr, Laurel and Hardy (U of California P, 1968), 68-69. [↩]

- Barr, Laurel and Hardy; John McCabe, Mr. Laurel and Mr. Hardy: An Affectionate Biography (Robson Books, 1976). [↩]

- Steven Cohan, “Almost Like Being at Home: Showbiz Culture and Hollywood Road Trips in the 1940s and 1950s,” in The Road Movie Book, ed. Steven Cohan and Ina Rae Hark (Routledge, 1997), 113-142. [↩]

- Marc Vernet, “The Look at the Camera,” Cinema Journal 28.2 (1989), 48-63. [↩]

- David Monod, Vaudeville and the Making of Modern Entertainment, 1890-1925 (U of North Carolina P, 2020), 59. [↩]

- Steve Neale and Frank Krutnik, Popular Film and Television Comedy (Routledge, 1990), 211-219. [↩]

- Jason Middleton, Documentary’s Awkward Turn: Cringe Comedy and Media Spectatorship (Routlege, 2016), 19, makes a similar point about The Office and other mockumentary sitcoms, arguing that “In effect, the documentary filmmaker’s camera both is and isn’t there.” [↩]

- McCabe, Mr. Laurel and Mr. Hardy 142. [↩]

Takipteyim kaliteli ve güzel bir içerik olmuş dostum.

I truly appreciate your technique of writing a blog. I added it to my bookmark site list and will

I am truly thankful to the owner of this web site who has shared this fantastic piece of writing at at this place.

You’re so awesome! I don’t believe I have read a single thing like that before. So great to find someone with some original thoughts on this topic. Really.. thank you for starting this up. This website is something that is needed on the internet, someone with a little originality!

I completely agree about the mockumentary style becoming purely conventional rather than satirical. When I watch Abbott Elementary, I rarely think about the supposed documentary crew – those camera looks just feel like natural moments of connection with characters. It’s fascinating how this evolved from laugh track prompts to something more intimate. The style has definitely transcended its original mockumentary premise to become its own storytelling language.