Robotic Slaves and Where to Find Them: Racial(ized) Servitude in The Jetsons

Golden M. Owens / University of Washington

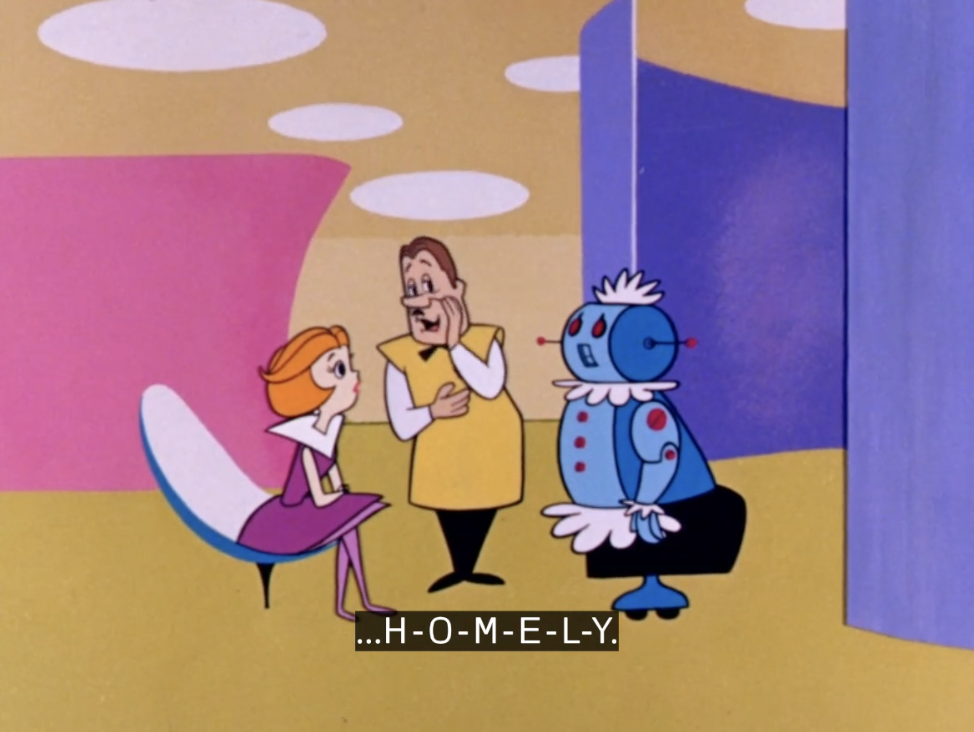

The premiere episode of The Jetsons introduces Rosey the Robot, a domestic servant ultimately employed by George and Jane Jetson and their children, Judy and Elroy. [1] Aptly titled “Rosey the Robot,” this episode sees Jane, distressed by housework, looking to rent a robot maid for assistance. Of the maids she views, Rosey stands out to Jane because of her eagerness and her sass: when the robot salesman calls Rosey “an old demonstrator model with a lot of mileage” and literally spells out that she is “H-O-M-E-L-Y,” Rosey responds: “I may be homely, buster, but I’m also S-M-A-R-T, Smart!” Liking Rosey, Jane brings her home, and the maid immediately starts working: she cleans, plays with Elroy, does Judy’s homework, and makes dinner, all in a few hours. Just after the Jetsons reluctantly dismiss Rosey, unable to afford her full-time, George’s boss—who had attended dinner and loved Rosey’s cooking—gives George a raise so the family can keep her. Rosey returns, asking how much the Jetsons will charge her to serve them, and proclaims her love for the family. The episode ends on an upbeat note, viewers left understanding that Rosey now belongs to the Jetsons indefinitely.

Rosey’s sass throughout the series, along with her large frame and immediate, joyful deference to the Jetsons, has led scholars like Gregory Jerome Hampton to dub her a robotic version of the Mammy: a Black housemaid archetype created during the U.S. antebellum to depict Black women as content if not happy with enslavement and domestic service. To Hampton’s point, Rosey is eerily similar to the Mammy: in addition to sharing sass, size, and submissiveness, both figures wear clothes that indicate their status; are older-aged; are fiercely protective of and loyal to “their” families, and are “maids of all work,” responsible for any and all domestic tasks.[2] Their dialects are also similarly othered: Rosey’s New Jersey accent is typically connoted with loudness, brashness, and lower-class status, while the Mammy’s Southern accent and so-called “Negro dialect” was long mimicked and mocked by white performers.[3]

Furthering Hampton’s assertion that Rosey is a futuristic, mechanical mammy, I find it pertinent to consider the conditions surrounding and enabling Rosey’s existence and employment in The Jetsons. In practice, Rosey’s Mammification is viable because of real-world constructs and understandings of domestic labor and the bodies best suited to perform it–a framework which predates the Mammy’s invention. This framing truly dates back to the transatlantic slave trade and justifications for African enslavement, which itself is tied specifically to Black women: in rationalizing chattel slavery, European writers described these women as beastlike, impervious to pain, and unfeminine, emphasizing their capacity for labor performance and downplaying if not erasing their humanness. Jennifer Morgan asserts that these writers marked Black women’s bodies as useful solely for “produc[ing] both crops and other laborers,” and thereby characterized these women as “mechanistic”—as machines instead of living beings.[4]

This mechanizing of Black women’s bodies enabled and arguably influenced the creation of the robot, which first appeared in the 1921 play R.U.R. As John M. Jordan observes, the word robot “derives from the Czech word ‘robota,’ or forced labor, as done by serfs. Its Slavic linguistic root, ‘rab,’ means ‘slave.’ The original word for robots more accurately defines androids, then, in that they were neither metallic nor mechanical.”[5] That the robot and its etymology are based on compulsory labor as performed by lower-class entities inevitably embeds enslavement and forced labor into the robot’s ontology. This attachment ensures that robot maids like Rosey are inevitably inflected by Black maids, free or otherwise: there is no such thing as a robot divorced from slavery or the enslaved, or from slavery’s influence on later forms of work—especially in the United States, where the term “slavery” immediately evokes America’s history of enslaving Black people. This interconnection also effectively marks Black people as robots; per Alondra Nelson, Black people are the first service instruments, service tools that are like robots, deemed to be both human and not-human. ‘The contemporary literature on robots is instructive: for them to be effective and useful (to humans), they have to be humanoid enough; we like when they have eyes and maybe the eyebrows go up and down, but they can’t be too human.’ [6]

Nelson’s words insinuate that there would be no robots without Black people, namely because Blackness (in Western societies) has always been robotized. The notion that robots cannot be too human supports this claim, evoking the ways white colonizers systematically eradicated Black people’s humanness to rationalize enslaving them.

Given this historical context, Rosey’s characterization becomes especially pernicious, recommunicating race and class-based ideas of labor and the often minoritized bodies “designed” to perform it through both her Mammification and what that symbolizes. Making Rosey a futuristic Mammy thus connects her to an extensive history of racialized labor in the United States–especially since most housemaids in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were Black women, who consequently became nearly synonymous with domestic service.[7]

The Jetsons pilot situates robot maids within this history even before Rosey appears. To show Jane prospective maids, her salesman seats her in an exhibition area and parades them before her one by one. As they stand before Jane, the salesman comments on their unique traits: he shares that the first maid, a “basic economy model” named Agnes, has a British accent because she last served an English teacher, and praises the hourglass physique and French origins of the second maid, Blanche Carte.[8] Notably, he specifically accentuates Blanche’s posterior, the maid showing Jane her backside as the salesman emphatically remarks that her engine is “in the rear, where an engine belongs.” Rosey is then similarly described, with the salesman particularly noting her old age and eagerness to work.

Presented comedically, this scene’s exhibition of robot maids eerily mirrors the auction block, where enslaved people were displayed before prospective enslavers—often in a forcibly joyful manner. Auctioneers presented Black people much like the robot salesman did his maids, highlighting their ages, physiques, physical strength, capabilities, and previous ownership. Auctioneers and prospective buyers had carte blanche to poke, prod, and otherwise interact with enslaved people as they saw fit, from forcing open their mouths to gauge their health to making sexual comments and advances—especially against women, whose hips and buttocks were often emphasized as indications of her reproductive capacity. The enslaved themselves were made to smile, speak and perform on command, and largely ignore each other, regardless of their inner feelings.[9]

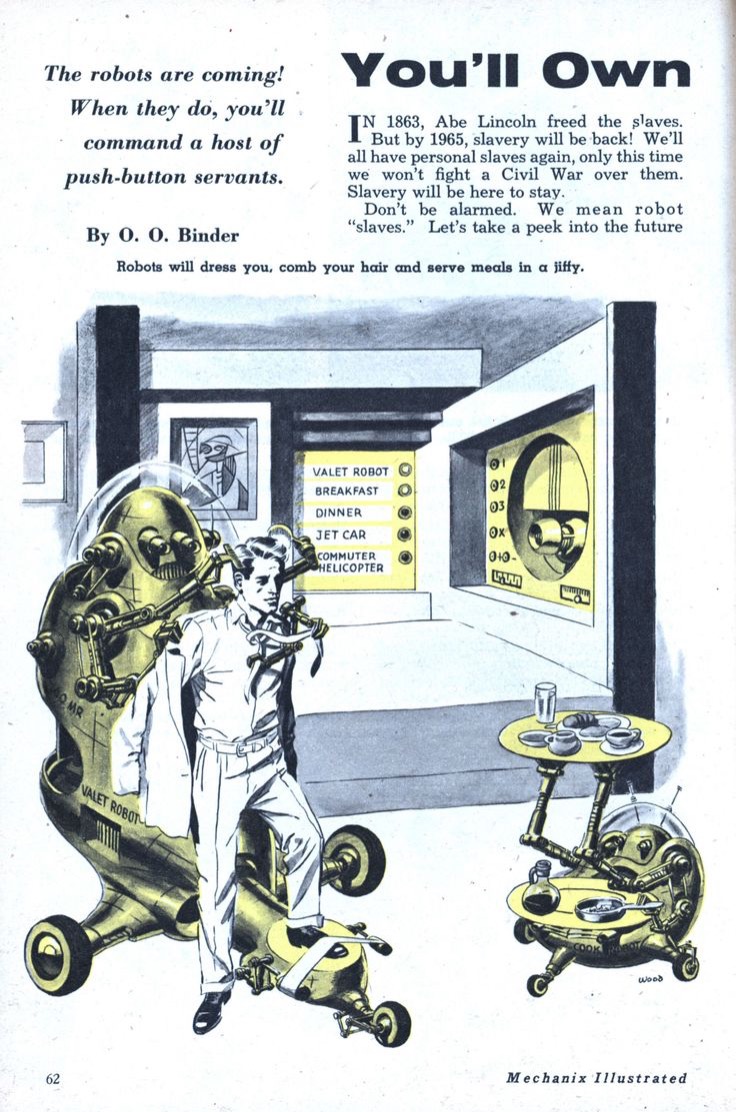

That the auction block is alluded to even before we meet Rosey demonstrates that the show’s allusions to racialized labor extend far beyond her: instead, they are central to the society Rosey exists in and the role robotic servants are meant to play within it. Far from being fun futuristic versions of human housemaids, Rosey and her ilk educe and reproduce the kind of master/slave society many wished to re-establish, particularly in the mid-twentieth century. Such desires are evidenced through ads like this (also included below), which assures (white) readers that owning robot servants will be akin to owning slaves.

By evoking the past while portraying the future, Rosey and The Jetsons demonstrate the intrinsic connections between past and present service technologies. As I argue in other work, nonhuman devices that perform domestic and domestic-adjacent tasks in the real world are similarly inflected and haunted by Black housemaids. As a mechanized servant clearly redolent of the Mammy, and thereby of the history of Black women as mechanized servants and slaves, Rosey helps elucidate how similar parallels can exist between Black women servants and our everyday servant technologies. Interrogating these parallels can foster deeper considerations of mundane technologies and their capacity to re-disseminate harmful ideals. Such considerations feel both relevant and critical in the present sociopolitical moment–especially as it attempts to recreate the past.

Image Credits:

- Warner Bros. Entertainment

- Photo by Bettmann Collection/Getty Images

- Screenshot from Episode 1 of The Jetsons

- Mechanix Illustrated (1957)

- In season one of The Jetsons, Rosey’s name was spelled as written in this article. The spelling was changed to “Rosie” in season 2. [↩]

- Not all housemaids were “maids of all work”; some only did 1-2 specific domestic tasks, often requiring households to hire more than one servant. For more on maids of all work, see Katzman 1978; Sutherland 1981; Clark-Lewis 1994; and Koman 1997. [↩]

- The “Negro dialect” long assigned to Black characters was based on white Americans’ perceptions of how Black people spoke. This dialect often incorporated poor diction, incorrect grammar, and misused words. For more on this dialect, see Stoever 2016; Eidsheim 2019; and Fuller-Seeley 2017. [↩]

- Jennifer L. Morgan, Laboring Women: Reproduction and Gender in New World Slavery (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), 14; “Mechanistic | English Meaning – Cambridge Dictionary.” https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/mechanistic. [↩]

- John M. Jordan, “The Czech Play That Gave Us the Word ‘Robot,’” The MIT Press Reader, July 29, 2019, https://thereader.mitpress.mit.edu/origin-word-robot-rur/. [↩]

- Niela Orr, “An Interview with Alondra Nelson,” Believer Magazine, January 31, 2020, https://www.thebeliever.net/an-interview-with-alondra-nelson/. Emphasis mine. [↩]

- Dill 2014; Jones 2010; Katzman 1978. [↩]

- The “joke” of Blanche’s name is not lost on me, and is alluded to in my discussion of the auction block. [↩]

- For more on the horrors of the auction block, and the forced performances leading up to it, see Hartman 1997. [↩]