How Art Entered the Screen Age

Anna Lovatt / Southern Methodist University

How did artists respond to the popularization of television in the mid-twentieth century, and the emergence of video in the decades that followed? What new opportunities did these media offer for making, exhibiting, and viewing contemporary art? How did artists in different parts of the world navigate culturally specific media landscapes? These are some of the questions posed by the exhibition Lines of Resolution: Drawing at the Advent of Television and Video, on view at the Menil Drawing Institute in Houston from October 4, 2025 to February 8, 2026.

An institute dedicated to modern and contemporary drawing might seem like a surprising venue for an exhibition about the early days of television and video art. But as the 2022 Research Fellow at the MDI, I began thinking about how these emergent media shaped drawing practices during the “network era”—that is, the heyday of network television from the mid 1950s to the mid 1980s. In collaboration with MDI Associate Curator Kelly Montana, I developed this research into an exhibition featuring twenty-five artists who greeted the dawn of the screen age in diverse and inventive ways.

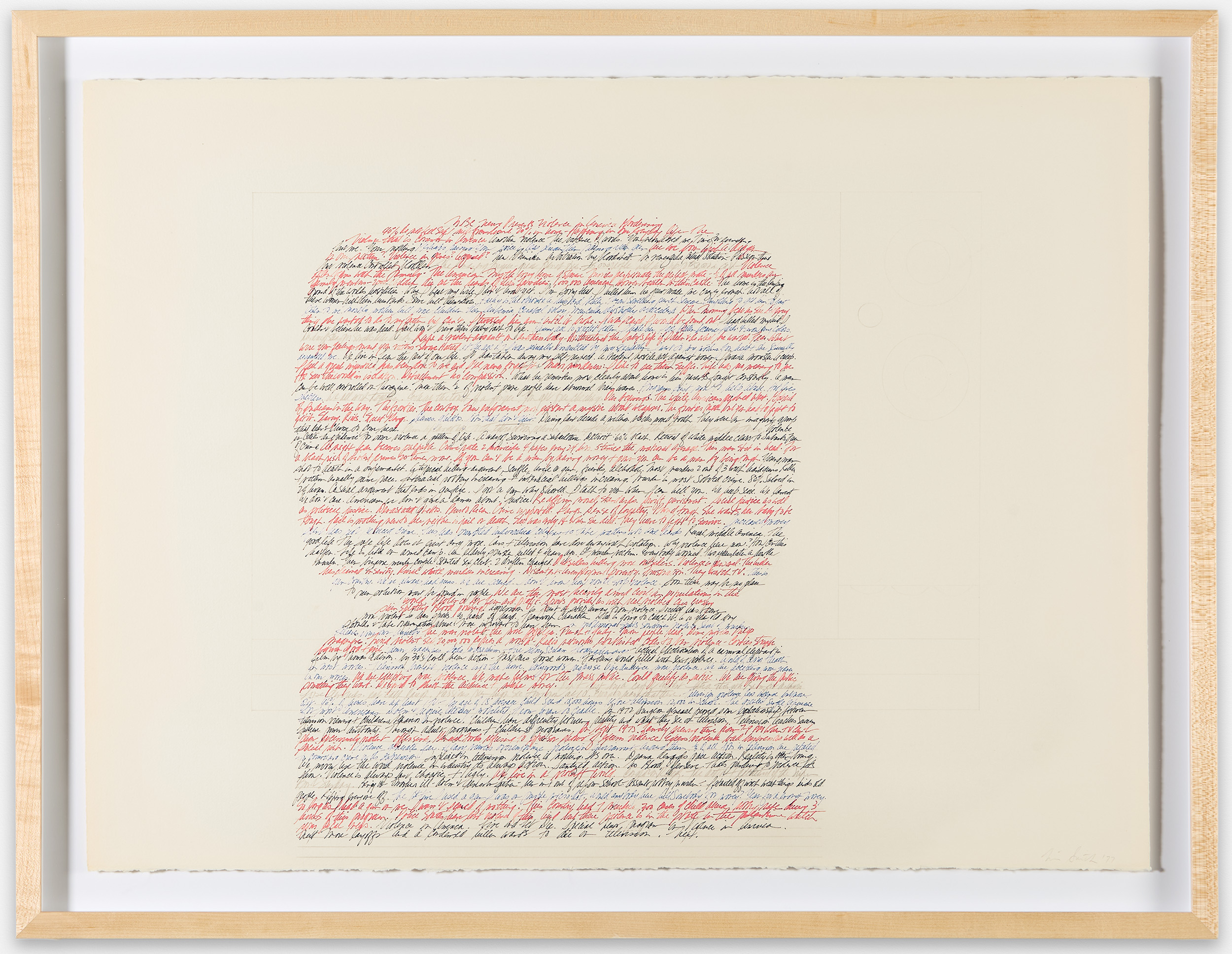

From the 1950s onwards, artists began to install television sets in their studios for the first time. Lines of Resolution includes drawings by American artists Philip Guston, Adrian Piper, and Robert Rauschenberg that are replete with televisual imagery and the boxlike form of the television set. As an artist and mother working from home in the mid 1970s, Mimi Smith found television meant that “the constant information of the world invading my studio and home was not avoidable.”[1] She began a series of “Television Drawings” where she transcribed news broadcasts into rectangular shapes with rounded corners, reminiscent of a TV screen. Violence in America, Good Evening, 1977 (Fig. 2) was based on a three hour NBC report on violence in American culture. The phrases “we live in fear” “detachment no compassion” and “shot to death in a supermarket” stand out in the barrage of information, which spills out of one screen-shape to form another below it, like the head and shoulders of a shadowy presence infiltrating Smith’s living and working space.

This flow of imagery from the outside world into the artist’s studio was not unilateral. In the 1960s and 70s, public television in Europe and the United States offered opportunities for artists to show their work to large and diverse audiences. In Germany, art broadcast pioneers Gerry Schum and Ursula Wevers directed a “television gallery” that organized exhibitions in the form of thirty-minute broadcasts made up of short videos by contemporary artists.[2] The exhibition Land Art, 1969, showcased inscriptions on the land by artists working in Europe and the USA including Walter de Maria, Jan Dibbets, Michael Heizer, Richard Long, and Dennis Oppenheim; while Identifications, 1970, featured twenty artworks including drawing-based actions by Alighiero Boetti, Gary Kuehn, and Mario Merz. In the U.S., Argentine-American artist Jamie Davidovich established the Artists Television Network in 1976 and went on to produce and host “public access Dada cabaret,” The Live! Show on Manhattan Cable Television’s Channel J from 1979 to 1984.[3]

As well as using broadcast media to expand the audience for contemporary art, Davidovich was one of several artists including the Korean artist Nam June Paik and the American artist Howardena Pindell who used the television set as a drawing tool. Lines of Resolution features Blue, Red, Yellow, 1974 (Fig. 1), which sees him covering a static-filled TV screen with rolls of blue, red, and yellow adhesive tape—flickers of light still visible in the gaps between the opaque strips. These lines mimic the raster pattern of the electron beam in a cathode ray tube, which reconstitutes the image on an analog TV screen by scanning from top to bottom and left to right. In analog television and video systems the image was captured, transmitted, and displayed in lines, with the phrase “lines of resolution” referring to the amount of detail a system could resolve.

In addition to the television set, the video camera offered a transformative tool for artists interested in themes of performance, interaction, and surveillance. Fifty years ago, Nina Sobell invited visitors into a living-room environment at the Contemporary Arts Museum in Houston. Working with two participants at a time, she attached electrodes to their scalps, recording the electrical activity of their brains with an electroencephalograph (EEG) and an oscilloscope located in a separate room. The participants focused on the monitor, where they could see a live video feed of themselves overlaid with two intersecting lines representing their brainwave frequencies.[4] Rather than watching television, participants controlled the video tape recorder on the coffee table in front of them to archive these collaborative “BrainWave” drawings, examples of which are on view in Lines of Resolution.

The exhibition also foregrounds the work of second wave feminist artists who performed the act of drawing for the camera, including Sanja Iveković in the former Yugoslavia, Suzy Lake in Canada, and Letícia Parente in Brazil. In Preparação 1, 1975, Parente stands in front of a bathroom mirror and brushes her hair, before applying strips of tape to her mouth and eyes, using makeup to draw her facial features on top of this tape. Blindfolded and gagged, she ruffles her hair, pats her face and smooths her sweater before leaving the room. Parente described this work as a commentary on “the oppression and censorship of lucidity and speech,” referring to the military dictatorship then governing Brazil.[5] What might initially appear to be an uncanny makeup tutorial is, in fact, a poignant commentary on processes of concealment and silencing operative in the media and in everyday life.

Lines of Resolution ends in the mid-1980s, when the “multichannel transition” saw the proliferation of cable channels, increased use of videocassette recorders, and invention of the remote control—systems and devices that allowed viewers to build their own viewing schedules, loosening the grip of the big television networks.[6] The year 1986 also saw the introduction of the first digital video cameras, which produced higher quality images that could be reproduced without degrading.[7] Combined with the increasing affordability of video-editing software, these developments led to higher production values in video art of the 1990s and 2000s, paving the way for the technologically complex, multichannel video installations now ubiquitous in international exhibitions of contemporary art.[8] Yet the early engagements with television and video showcased in Lines of Resolution prefigure developments like the touchscreen as a drawing surface or the makeup tutorial as activist gesture. In works like Parente’s, they show how the appropriation and reconfiguration of televised messages can offer a means of resistance and critique.

Image Credits:

- Fig. 1. Jaime Davidovich, Blue Red Yellow , 1974

- Fig. 2. Mimi Smith, Violence in America, Good Evening

- Fig. 3. Nina Sobell, EEG Video Telemetry Environment

- Fig. 4. Letícia Parente, Preparação 1, 1975

- Mimi Smith, statement accompanying the “Television Drawings” on the website of gallery Luis De Jesus

Los Angeles, https://www.luisdejesus.com/index.php/artists/mimi-smith/series/television-drawings. [↩] - See Ursula Schum-Wevers, ed., Ready to Shoot: Fernsehgalerie Gerry Schum, Videogalerie Schum (Düsseldorf: Kunsthalle Düsseldorf; Cologne: Snoek, 2004). [↩]

- Ava Tews, “Jaime Davidovich’s The Live! Show (June 25, 1982), https://features.eai.org/video-features/jaime-davidovichs-the-live-show-june-25-1982. [↩]

- Christina Albu, “Intimate Connections: Alternative Communication Threads in Nina Sobell’s Video Performances and Installations (1974–82),” Camera Obscura 35, no. 1 (May 1, 2020), 39-41. [↩]

- Parente cited in Kelly Montana, “Drawings for the Video Camera: Resolving the Self,” in Anna Lovatt and Kelly Montana eds., Lines of Resolution: Drawing at the Advent of Television and Video (Houston: Menil Drawing Institute/Distributed by Yale University Press, 2025), 43. [↩]

- Amanda Lotz, The Television Will Be Revolutionized, (New York: New York University Press, 2007), 25. See also Lotz, We Now Disrupt This Broadcast: How Cable Transformed Television and the Internet Revolutionized It All, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2018). [↩]

- Whereas analog video transmits information as a continuous signal, digital video converts it into a binary code of zeros and ones. [↩]

- On the emergence of video installation in the late 1980s and early 1990s, see Barbara London, “The Rise of Installation,” in Video Art: The First Fifty Years (London: Phaidon, 2020), 159–180. [↩]