“Just let people be!”: The Assembly, inclusivity, and aspirational feeling

Helen Piper / University of Bristol

The Assembly is a new television talk show which stages the interrogation of the (culturally prominent) few by the (less visible) many—the latter being a “collective of autistic neurodivergent and learning-disabled interviewers”. The premise was original to the French show Les Rencontres Du Papotin (france-tv, 2022- ) and has since been adapted for at least thirteen different territories including Singapore, Poland, and Australia. Although, as Jean K. Chalaby has long since acknowledged, “formats travel precisely because they adapt to local tastes”,[1] the commercial success of every articulation is sometimes assumed to be a foregone, formulaic conclusion. Instead, I argue that creative choices about the manner of presentation achieve nuances of mood and tone which are crucial to the value an audience may derive from a programme. Additionally, like most factual entertainment formats built around unscripted encounters between contributors, The Assembly encourages feelings linked to risk—that is, to the possibility that something might, at any point, ignite, or misfire.

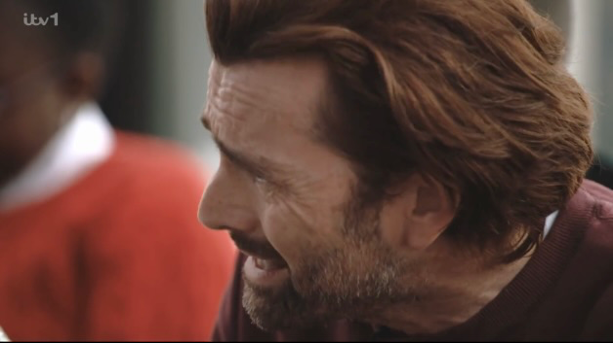

In the second episode of The Assembly UK (ITV, 2025), Scottish actor David Tennant exits a lift and walks briskly to the interview space followed by a floor manager and two visible camera operators. It is a sociable, egalitarian sort of an entrance—he is casually dressed in sweatshirt and jeans, looking right and left as he cheerfully greets the handful of people gathering in a high-rise office space, bathed only in natural light from floor-to-ceiling glass windows (Fig. 1).

This mise-en-scène-in-progress is clearly a far cry from the curated warmth (comfy chairs, ambient lighting, vibrant colour) of prime-time celebrity chat: evident, for example, in this image of The Graham Norton Show (BBC, 2007- ) on which Tennant has also been a fairly frequent guest (Fig. 2).

For the British version of The Assembly, there is no stage, no host presenter, and no voice-over, just an occasional glimpse of a facilitator who cues each interviewer to ask their question. Every episode begins with identical announcements as to the event rules: “no subject is out of bounds, no question is off the table, and anything might happen”. In practice, the interrogations which follow are eclectic, engaging, and respectful. Questions are direct, certainly, but perhaps more refreshingly, they clearly matter to those asking them. For example, Tennant is asked whether he believes in God and how he felt when he became the tenth Doctor Who. He plays out a scene from Macbeth with Luka and is taught a series of dance moves by Sophie (Fig. 3). He appears as interested in his interviewers as they are in him. When asked by Sammy about the death of his parents, Tennant responds openly, then asks her the same question, commiserating over the loss of her mother.

Reciprocity is inclusive, of course, and encourages the proceedings to move beyond a formal Q & A and become a dialogue during which speakers can freely disclose subjects close to their hearts. Essin commends Tennant on his support for the trans movement and asks about his being publicly “called out” on the topic by J. K. Rowling. A response will clearly require some diplomacy, but Tennant replies with the generality that “I hope that we can all, as a society, just let people be…just get out of people’s way!” (Fig.4). The statement is simultaneously pointed and de-politicising yet articulates an aspiration that could usefully serve as a tag line for this entire television series.

As I suggest elsewhere, television entertainment has the potential to actively produce “affective communities”, not just through on-screen representation but amongst off-screen viewership(s) who may feel affinity with others as a virtual collective drawn into being by the show itself.[2] Such imaginary communities are often conjoined by a shared aspiration to the values exemplified by a programme, uniting their members in a sense of belonging which is cultivated by aesthetic means. The multi-camera set up and uncensored energy in the space of The Assembly make it feel ‘as live’, perhaps as if it were edited inline, but as the availability of many ‘unseen’ clips makes clear, each show is heavily post-produced. This enables frequent cutaways to close-up reaction shots that guide audience appreciation: effectively aligning the home viewer with the responses of the celebrity and collective alike—whether they are laughing, drawing breath at a risky question, or shedding a tear of empathy.

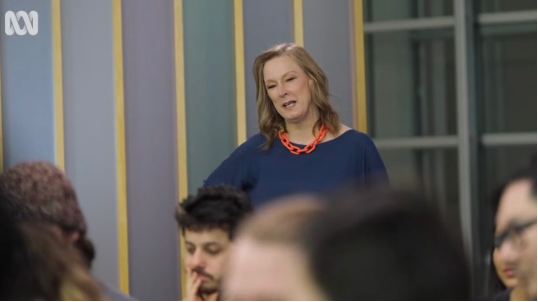

Curiously, in the Australian version of The Assembly (ABC, 2024), the mutual intimacy of the unscripted encounters is impeded by their framing as a teaching exercise. Here the assembly members sit at a more formal distance from the interviewee, having been introduced as “aspiring journos” who need to “rise to the challenge” of the situation. They have a famous on-screen mentor, current affairs presenter Leigh Sales, who doubles as the show’s host, and whose own tutorial guidance is allowed to interrupt the intimacy with the guest celebrity (Fig. 5). It is perhaps for good reason then that this particular regional version has been critiqued as inherently ableist by Australian disability commentators, including Elly Desmarchelier, who argues that the didactic premise implies a need for the neuro-divergent questioners ‘to “fit in” with neurotypical standards’.[3]

ABC’s marketing of the show also includes a number of online post-show video debriefs in which celebrity interviewees reflect on their involvement and commend the quality of the questions they were asked. However warmly appreciative the tribute, this kind of paratextual activity also seems to situate the show within a previously dominant reality television tradition, by which inexpert folk are schooled in effective personhood through expert intervention. Instead of exemplifying a shared aspiration that everyone might be allowed to simply “be”, the interviewers themselves must aspire to celebrity and tutor approval. The introduction of judgement inevitably confounds the format’s more radical potential to give unconditional voice to difference.

At the end of Tennant’s interview some of his questioners present a performance of The Proclaimers hit, ‘Sunshine on Leith’ (Fig. 6) by which he is demonstrably moved (Fig. 7).

Ending each episode with a significant musical number was a calculated decision by the disabled-led production company, Rockerdale Studios, who saw in it an opportunity to avoid some of the more “patronising” qualities they had noted in the original French version.[4] In this particular instance, the performance culminates in a spontaneous decision by the rest of the cast to join in—to sing and dance without inhibition in a celebration of pleasure and feeling. As Sara Ahmed reminds, institutional declarations of diverse inclusivity are always, and perhaps only ever, part of “an appearance of valuing.”[5] However, appearance is also one of the ways in which television can model ideal ways of acceptance and belonging for audiences. If we can accept such a capability as an internally significant end in itself, then a final impromptu expression of communality and shared experience is perhaps the most valuable of all this format’s possibilities.

Image Credits:

- David Tennant arrives for The Assembly (UK, ITV, 2025) [author’s screengrab]

- Tennant on the stage sofa for The Graham Norton Show (S:30 E:1, 2022) [author’s screengrab]

- Tennant learns a dance routine in The Assembly UK [author’s screengrab]

- “Just let people be!”, The Assembly (ITV, 2025) [author’s screengrab]

- Leigh Sales mentors the students, The Assembly (Australia, ABC, 2024) [author’s screengrab]

- Performance of ‘Sunshine on Leith’ in The Assembly UK [author’s screengrab]

- Tennant watching performance of ‘Sunshine on Leith’ in The Assembly UK [author’s screengrab]

- Jean K. Chalaby, ‘The making of an entertainment revolution: How the TV format trade became a global industry’, European Journal of Communication, vol. 26 no. 4, 2011, pp. 293-309, (p. 306). [↩]

- Helen Piper, Hopeful Vision: Entertainment on The Small Screen, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2025, p. 94-95. The phrase ‘affective community’ is repurposed from Veronika Zink’s coinage, see V. Zink, ‘Affective Communities’ in Affective Societies: The Key Concepts, ed. by J. Slaby & C. von Scheve, London & New York: Routledge, 2019, pp. 289-299. [↩]

- Elly Desmarchelier, ‘“The Assembly” misses the mark: here’s how I’d get it back on track’, The Disability Dialogue, 2024. Available at: https://disabilitydialogue.com.au/the-assembly-misses-the-mark-heres-how-id-get-it-back-on-track/ (accessed 26 August 2025). [↩]

- Michelle Singer cited in ‘Producers wanted to avoid being ‘unpleasant’ to interviewers on The Assembly’, Craven Herald & Pioneer, 23 April 2025. Available at: https://www.cravenherald.co.uk/leisure/national/25111356.producers-wanted-avoid-unpleasant-interviewers-assembly/ (accessed 26 August 2025). [↩]

- Sara Ahmed, On Being Included : Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life, Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2012, p. 59. [↩]

Nice!

he is casually dressed in sweatshirt and jeans, looking right and left as he cheerfully greets the handful of people gathering