Silicon Valley’s Human Shields

Gerald Sim / Florida Atlantic University

With the tableau of Big Tech CEOs perched at the presidential inauguration still fresh in the collective memory, the summer of 2021 feels like a lifetime ago. That June, Lina Khan was confirmed to the Federal Trade Commission with almost 70 votes in the US Senate and sworn in as chair the same day. ‘Twas truly the season. Not one but two different antitrust bills to curb the power of platform companies were making their way through Congress. The American Innovation and Choice Online Act (AICOA) sought to prevent platforms from favoring their own products, while the Open App Markets Act (OAMA) would have made it illegal to force developers into using an in-app payment system. Those were halcyon days of a bipartisan techlash, when a platoon of proto-Khanservatives fell in formation with a squad of freshly techno-literate and mildly courageous liberals.

Tech behemoths have been aggressive in both their investments and strategies in legislative lobbying for some time, armed with resources that engender more power than ever to stymie opposition to their agenda. The effort takes place on two fronts. Traditional “inside” lobbying relies on direct access to decision-makers in parties and government, whereas the “outside” game uses media campaigns to raise popular support and exert public pressure. Unlike Big Oil and Big Pharma, the most highly capitalized members of Big Tech are also media companies. This techno-media-industrial complex possesses the financial wherewithal as well as new abilities to mobilize the thoughts and actions of millions.

Television spots such as the “Harry and Louise” ads from the Clinton era are still part of messaging strategies, but they are blunt instruments with unpredictable returns on investment. A recent comprehensive study found no correlation between ad features such as “messenger, message, tone, ask, and production value” and effectiveness. Social media platforms have, however, discovered a more potent tool. They can move lawmakers’ votes with a well-crafted prompt or stoke public ire with customized incentives.

Efficacy aside, Big Tech’s outside lobbying entails media strategies for mass engagement that proffer a readable index to public understandings and sociotechnical imaginaries of data-driven technology. The industry’s writ against the AICOA and OAMA was carried in part by a slate of issue ads on cable television and streaming platforms like YouTube, produced by groups like the Taxpayers Protection Alliance (TPA, which receives funding from Google, Amazon, and Facebook) and American Edge Project (AEP, which received $34 million from Facebook during this key period). Although the video pronouncements rehearse a visually anodyne vocabulary and syntax, they reify technoliberal social relations in a manner that deserves scrutiny.

TPA ads against AICOA from 2022 feature regular people in different occupations—known to students of propaganda as “plain folks”[1]—reciting a structured script. They introduce themselves and their financial struggles, criticize Washington liberals for attacking “America’s tech innovators,” and highlight the threats posed by the bill to the economy and national security. Ominous images of the Chinese flag and military parades subsequently underline dangers from the East. As an anti-tax, anti-regs outfit, TPA veers staunchly right. The spots conclude with a directive to contact specific lawmakers, namely Republicans on the Senate Judiciary, Finance, and other Committees with purview over small business and technology.

These “real Americans” rising to the defense of tech innovators are pictured performing manual labor—a machinist turns the lever on a drill press, a rancher grips the bars of a stable stall, homemakers pump gas and put groceries away. With one exception, the cast of working people is white. The ads do not explain how AICOA would affect their livelihoods but clearly imply that the law would place the folks’ jobs and way of life at risk. “Working people like me will pay the price.”

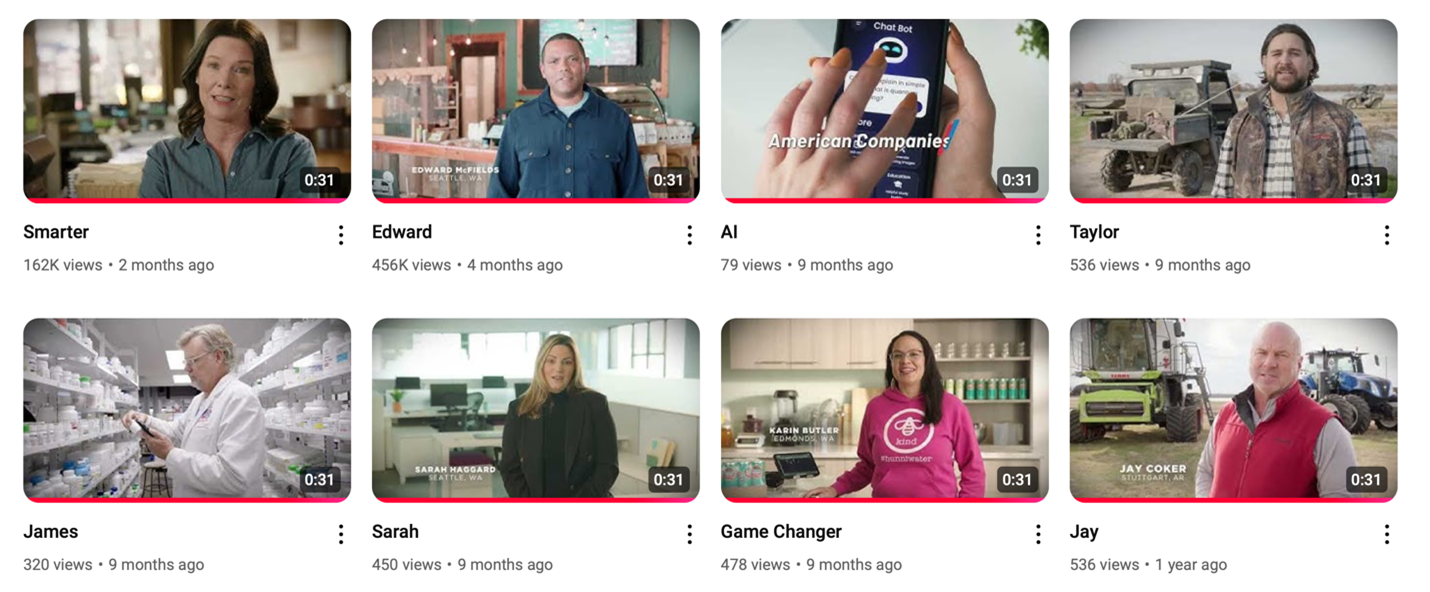

An ad that AEP released in 2021 between Khan’s nomination and confirmation to the FTC warns of the toll previously exacted from an earlier generation of working-class whites. “Powerhouse” opens with washed-out images of urban blight, hollowed factories, and abandoned homes. We see a lone forklift operator through a camera tracking backwards, moving away from him. A voiceover accusing politicians of turning their backs on American manufacturing alludes to NAFTA: “Factories closed, jobs went overseas.” The desolate location is unnamed, but the snow-covered ground makes it consonant with the Rust Belt’s decades-long decline. The 2024 election carried potentially huge ramifications for Big Tech. The fate of Merger Guidelines jointly released in late 2023 by the Justice Department and Khan-led FTC hung in the balance. The stakes for AEP funder Meta were especially high in the ongoing antitrust suit challenging the company’s acquisition of Instagram and WhatsApp. Throughout the year and into 2025, AEP released a series of ads featuring small business owners extolling the value of artificial intelligence and other “digital tools.” Unlike TPA, AEP is assiduously bipartisan. The ads don’t cite specific legislation, but decry the “misguided agenda” of Washington lawmakers who should instead be working to preserve the US’s “competitive edge” in tech.[2]

Compared with the 2022 TPA ads and the mental images conjured by “Powerhouse,” the visages in AEP’s lineup are equally homogenous. These continual evocations of white loss typify the technoliberal fantasies that Neda Atanasoski and Kalindi Vora question in their inimitably generative book, Surrogate Humanity.[3] The authors paint technoliberalism as “the political alibi of present-day racial capitalism,” projecting figurations of technological transformation that efface “uneven racial and gender relations of labor, power, and social relations” driving the current tech boom (4). To wit, “innovation” may be vital to the teachers, veterans, and entrepreneurs headlining AEP’s ads, but it can’t exist without violent exploitation of mine workers extracting conflict minerals in the DR Congo and Rwanda, content moderators in the Philippines, India, and Kenya, and Chinese iPhone factory workers.

China is of course a major part of the conversation, both as a national security threat and rival in the AI race that America cannot afford to lose. Anti-antitrust ads constantly cite the nationalistic “China Argument” that impinging on Silicon Valley’s free reign risks American AI supremacy. It’s a useful boogeyman and cudgel, but beware every denunciation of foreign adversaries like China that “believe in oppression and censorship, and … want to dominate and use tomorrow’s technologies against America.” Not long before Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg changed his tune, he was showing off Mandarin skillz to audiences in Beijing, asking Xi Jinping to name his firstborn, and assenting to that very “oppression and censorship” for China’s 1.4 mouthwatering billion potential Facebook users.

All the same, Chinese comms strategy may not be very different even if the conscripts are racially diverse. TikTok wages the public relations war over its US ban by touting self-commissioned economic studies that demonstrate the app’s benefit for small businesses, especially those owned by women, older adults, and racial minorities. The reports are linked from TikTok webpages that depict the Obama coalition in all its postracial glory. And when the company staged an astroturf protest outside the US Capitol for CEO Shou Zi Chew’s congressional testimony in 2023, it curated an identical spectrum of more than two dozen influencers for the cameras.

Uber and Lyft adorned themselves with the same colors when they framed the vote for Proposition 22 as a fight for social justice. The California law took away employment rights from platform workers and allowed the companies to treat them as independent contractors, which are unprotected by state work laws.[4] This follows “Uber Presents: Da Republic of Brooklyn,” a series of five aspirational shorts directed by Spike Lee that profiles a majority-minority group of young borough residents funding the pursuit of their dreams with an Uber hustle.

The variation exhibited by these ads, in how far they turn the color dial, or how they address audiences that lean red or blue, belie an ideological consistency. Whether funded surreptitiously through super PACs, or co-branded as a Spike Lee joint, they nurture a technoliberal postracialism that disavows technology’s reliance on gendered and racialized labor. And should you otherwise believe that there’s still work to be done on racial inequality, technology is promised as the means to achieve utopia.

Currently archived on YouTube, these ads might already be relics. Emboldened by direct access to power, and newfound willingness to do whatever’s necessary to maintain it, does Silicon Valley still need to care what we think? If not, it is time to let them know that we see through these gauzy images of people who are supposed to be just like us, that we won’t be distracted by a new Red Scare, and that neither our aspirations nor our anxieties are to be weaponized against the primary means we have to keep Big Tech at bay.

Image Credits:- Photo by Maria Oswalt on Unsplash.

- “Tell Senator Cotton to Reject S.2992 – 30 secs” 2022

- “Rancher David Luther urges Sen. Thune to Stand Up for American Tech and Security” 2022

- “Powerhouse” 2021

- Screenshot from American Edge Project YouTube channel video menu. Accessed 2025

- Screenshot from “Rancher David Luther urges Sen. Thune to Stand Up for American Tech and Security” 2022

- “Uber Presents: Spike Lee (Trailer) | Da Republic of Brooklyn” 2018

- Alfred McClung Lee and Elizabeth Briant Lee, The Fine Art of Propaganda: A Study of Father Coughlin’s Speeches. Institute for Propaganda Analysis (Harcourt, Brace and Co, 1939), 92-94. [↩]

- The irony of wanting to maintain a “competitive edge” by thwarting antitrust laws should not be lost here, or for what it’s worth, the willingness of the CCP to crack down on tech monopolies like Alibaba. [↩]

- Neda Atanasoski and Kalindi Vora, Surrogate Humanity: Race, Robots, and the Politics of Technological Futures (Duke University Press, 2019). [↩]

- Veena Dubal, “The New Racial Wage Code,” Harvard Law and Policy Review 15 (2021): 513, 515. During early fights for market share, Uber also positioned itself as an antidote to racist taxi-drivers. [↩]