”Real EMO”: Mythologizing and Marketing EMO Music

Francesca Sobande / Cardiff University

Emo is back. To some, the music genre that is known for embracing emotional lyrics and equally brooding aesthetics never left. After all, as Fathallah (2020) affirms, while mainstream media interest in it may ebb and flow, emo is essentially a subculture defined by fans. Regardless of whether you have been a firm emo fan for decades, it is clear the genre is experiencing renewed attention across domains of digital, popular, and consumer culture. This has culminated in misty-eyed music festivals such as When We Were Young in Las Vegas, where fans are encouraged to embrace the genre’s “golden years” and feel “forever young”, begging the question: what messages are part of the mythologizing and marketing of emo today?

As the research of Hesmondhalgh (2008: 329) highlights, “Music is now bound up with the incorporation of authenticity and creativity into capitalism, and with intensified consumption habits”. Additionally, “[e]motional self‐realisation through music is now linked to status competition” (ibid.). Therefore, it is unsurprising that brands, including festival organizers, attempt to cash in on nostalgic notions of emo that have emerged since the genre sprung from a 1980s/90s post-punk and hardcore lineage.

Emo’s nostalgic status may be an inevitable part of time passing since the genre’s inception. Then again, as emo’s mythologizing dovetails with a resurgence in new millennium commodities, much emo nostalgia also makes a nod to the early(ish) days of the internet and the schism between then and now (Doherty 2023; Sobande 2022a). Relatedly, the playful opening of the video for “Spray Paint It Black” by emo luminaries Hawthorne Heights features them pretending to express concern about a friend (Anthony Raneri of Bayside) who is “posting these weird videos talking about NFTs and Reddit stocks…”. Such words signify that much has changed since the time that the video aesthetically harks back to via an exaggerated, thick-fringed black wig that connotes 2000s/2010s emo.

Beyond the way that allusions to the “realness” of the genre are relegated to the past and its celebrations, emo is often discussed within reductive binaries. Messages about emo and/as digital, popular, and consumer culture are reduced to discourses of praise versus periphery and by-product of the music industry versus departure from it. As Klein’s (2020) research points out, to gain a meaningful and in-depth understanding of dynamics between culture, commerce, and popular music, it is essential to move beyond narrow notions of supposedly “selling out”. Hence, it is important to acknowledge that emo’s entanglements with commercial activity are not new (Greenwald 2003; Markian 2019).

Even when emo was once viewed as marginal to the mainstream, the machinations of capitalism still contoured experiences of the genre, such as bands being (un)signed by a label (Payne 2023). Also, it is not just contemporary popular culture (e.g., TV and film) that has engaged with emo, including by fondly poking fun at it. More than a decade after its release, the horror/comedy movie Jennifer’s Body (2009) is still a relevant example of the genre’s mythologizing in recent popular culture history, as it addressed gendered dimensions of the genre’s scene and it “Captured Myspace-Emo Camp in All Its Glory” (Ewens 2018).

Put differently, nostalgic narratives of emo also often point to nostalgic narratives of digital and consumer culture – a romanticization of being online/offline before the social media sites and surveillance capitalism of today, paired with invocations of an elusive “realness” that the genre of yesteryear is discursively imbued with. Relatedly, the work of Williams (2023) on fandom practice and the internet outlines that, “[f]rom Limewire to Live Journal, street teams to stan armies, there has been no shortage of pioneering activities in the last three decades that have changed the way we think about music consumption, and in turn, youth culture”. Although the genre of emo has aged, its association with youth has stayed put, raising questions about what today’s mythologizing and marketing of emo suggests about the contentious relationship between the genre, ideas about authenticity, youth, and digital, popular, and consumer culture.

From One Tree Hill (2003–2012) (which Pete Wentz of the band Fall Out Boy had a brief role on) to Laguna Beach (2006–2010) (which Chris Carrabba of Dashboard Confessional was a guest Music Supervisor on) – there are many teen-oriented 2000s/2010s TV shows that emo music soundtracked or featured in as part of key plots. Another prime example is the Canadian teen drama series Degrassi: Next Generation (2001–2015) which, as part of the Degrassi franchise, is a nostalgic new millennium text of its own, deemed a revival of its predecessors Degrassi Junior High (1987–1989) and Degrassi High (1989–1991).

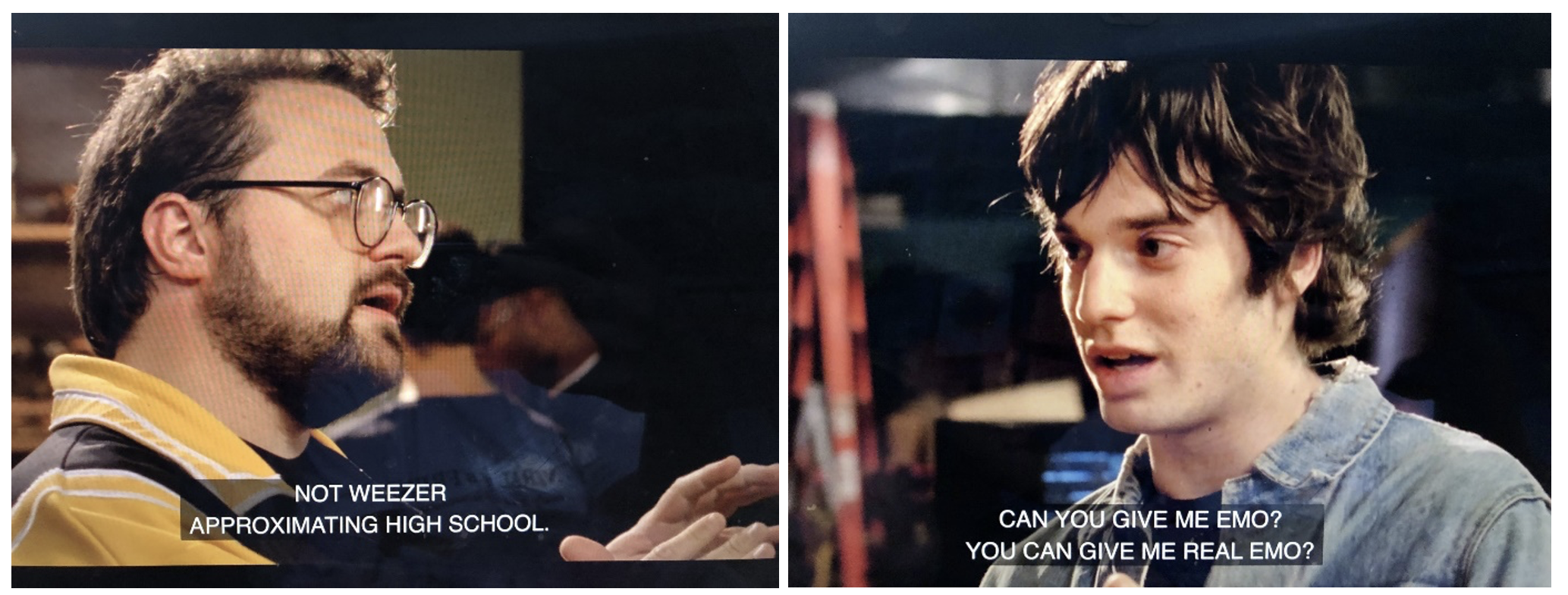

Degrassi: Next Generation includes a guest appearance from Taking Back Sunday, and features songs by Red Jumpsuit Apparatus and Silverstein in the background of various scenes. However, episode 20 of season 4, “West End Girls” (2005), might take the title of ‘peak emo’ in the series and offers a glimpse of messages about emo, youth, and authenticity that made their way onto the small screen in the 21st century. In that episode, featuring American director and producer Kevin Smith as a fictionalized version of himself, a teen protagonist and musician Craig Manning (played by Jake Epstein) is encouraged by Kevin to “Give me something high school, dude. Real high school. Not Weezer approximating high school. Can you give me emo? You can give me real emo?”.

In response to Kevin, Craig simply states: “I can give you real emo”. The brief exchange is an on-screen representation of some of the tensions that have surrounded emo – a genre that is both alternative and mainstream, both high school (young) and approximating high school (aging), both marketed and real.

In the decades since that episode of Degrassi: Next Generation aired, emo has experienced an ascent that has resulted in its mythologizing by brands that stand to gain from being in the business of marketing emo as an experiential commodity (e.g., an expensive and digitally documented festival experience). Beyond the fact that they are entwined with emo’s cultural zeitgeist status, digital, popular, and consumer culture have also resulted in the remixing and memetic historizing of the genre, whereby visual signifiers, such as throwback emojis and avatars, become a shorthand for emo “realness”. More recently, the viral memetic coverage of when NBA player Jimmy Butler “went full emo” brought attention to the ways that ideas about who and what is emo continue to play out in digital and popular culture, including via Black digital culture.

The intertextual depiction of emo on screen(s) demands further scholarly attention, particularly at a point in time when 2000s/2010s popular culture texts are being revisited, remixed, and rebooted at a rapid rate. As a genre that has never shied away from irony and satire, it makes sense that emo is taken up as part of marketing and branding activity that is in on the joke, but who ultimately benefits from such messaging? As the waters between the mythologizing, marketing, and making of emo music stay muddy, the potential for the genre to be reframed in revisionist ways looms large. So does the potential for brands to repel fans by corporatizing the DIY and communal spirit of emo, critiques that have been levelled at festivals such as When We Were Young.

Emo endures for many reasons beyond its potential to turn a profit for corporations. These include the sense of catharsis, contemplation, and comfort that it can provide fans, such as when recalling or learning about older emo eras, while also enjoying rerecorded, rereleased, and new music (Sobande 2022b). As its renaissance in present day digital, popular, and consumer culture suggests, enjoying emo is not simply about yearning for the time when music file-sharing platforms were still new. Still, nostalgia continues to be at the core of much of the mythologizing and marketing of the genre, suggesting that “real emo” is ultimately a contested construct of mediated remembrance, based on both fact and fantasies of the past.

Image Credits:

- When We Were Young Festival Entrance. Festival entrance sign, October 23, 2023, photograph by Francesca Sobande; festival entrance sign in the distance and the backs of festival attendants in the foreground, October 23, 2023; photograph by Francesca Sobande.

- Music video for “Spray Paint It Black” by Hawthorne Heights.

- Megan Fox and Kyle Gallner in Jennifer’s Body. Jennifer’s Body “I am going to eat your soul” GIF, @Lulu on Pinterest; Jennifer’s Body “Well, I’m glad you didn’t die” GIF, Tenor.

- Kevin Smith and Craig Manning (played by Jake Epstein) in Degrassi: Next Generation. Screenshots from season 4, episode 20 (“West End Girls”), taken by Francesca Sobande.

- Lyrics from “Smashed Into Pieces” by Silverstein, written on the sidewalk near the venue of When We Were Young. GIF created from a photograph by Francesca Sobande.

Doherty, Kelly (2023) “How AbsolutePunk.net helped emo fans find an online community from the early ’00s-2010s”. Alternative Press, February 14. Available at: https://www.altpress.com/absolute-punk-dot-net-history/

Ewens, Hannah (2018) “‘Jennifer’s Body’ Captured Myspace-Emo Camp in All Its Glory”. Vice, November 6. Available at: https://www.vice.com/en/article/qvqd3q/jennifers-body-bisexuality-00s-myspace-emo-essay

Fathallah, Judith (2020) Emo: How Fans Defined a Subculture. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press.

Greenwald, Andy (2003) Nothing Feels Good: Punk Rock, Teenagers, and Emo. New York: Griffin.

Hesmondhalgh, David (2008) “Towards a critical understanding of music, emotion and self‐identity”. Consumption Markets & Culture 11(4): 329–343.

Klein, Bethany (2020) Selling Out: Culture, Commerce and Popular Music. London: Bloomsbury.

Markian, Taylor (2019) From the Basement: A History of Emo Music and How It Changed Society. Coral Gables: Mango Media.

Ozzi, Dan (2021) Sellout: The Major-Label Feeding Frenzy That Swept Punk, Emo, and Hardcore (1994–2007). New York: Dey Street Books.

Payne, Chris (2023) Where Are Your Boys Tonight?: The Oral History of Emo’s Mainstream Explosion 1999-2000. New York: Dey Street Books.

Sobande, Francesca (2022a) “Welcome to When We Were Young’s Big Tech Parade”. Paste Magazine, October 27. Available at: https://www.pastemagazine.com/tech/when-we- were-young/when-we-were-young-festival-big-tech-netflix-googl

Sobande, Francesca (2022b) “Why emo endures: the comforting nostalgia of emo on vinyl”. The Vinyl Factory, November 9. Available at: https://thevinylfactory.com/features/emo-on-vinyl/

Williams, Jenessa (2023) “Tracing music fandom practice through the internet”. Museum of Youth Culture, September 1. Available at: https://museumofyouthculture.com/tracing-music-fandom-practice-through-the-internet/

Emo endures for many reasons beyond its potential to turn a profit for corporations. These include the sense of catharsis, contemplation, and comfort that it can provide fans, such as when recalling or learning about older emo eras, while also enjoying rerecorded, rereleased, and new music (Sobande 2022b). As its renaissance in present day digital, popular, and consumer culture suggests, enjoying emo is not simply about yearning for the time when music file-sharing platforms were still new. Still, nostalgia continues to be at the core of much of the mythologizing and marketing of the genre, suggesting that “real emo” is ultimately a contested construct of mediated remembrance, based on both fact and fantasies of the past.