Love Me, Love Me Not: Spectacularizing ‘Love Migration’ In Scandinavian Reality TV

Georgia Aitaki / Karlstad University

A ‘love migrant’ is someone who moves to a different country primarily due to romantic or marital motivations. Partner or family migration, as more official terms that describe the phenomenon in question, can be voluntary or forced, and can encompass various forms of relationships, including marriage, cohabitation, and dating. In the realm of entertainment, ‘love migration’ has been most straightforwardly spectacularized in TLC’s 90 Day Fiancé, an emblematic reality TV series that delves into the complexities of intercultural relationships between U.S. citizens and foreign partners. The show, both popular and contentious, grapples with issues surrounding love and conflict, but also migration, activating questions around gender, race, and social class within the context of contemporary border regimes.

The premise of 90 Day Fiancé revolves around the timeline dictated by the K-1 nonimmigrant visa, allowing the foreign-citizen fiancé(e) to enter the country and marry their U.S. citizen sponsor within 90 days of arrival. This 90-day window becomes a focal point, capturing the intense period in the couple’s life as they navigate cohabitation, intimacy, and meeting friends and family, all while planning their wedding. Through close observation of their day-to-day interactions, from tender moments to disagreements, misunderstandings to compromises, separations to reconciliations, the show sheds light on the challenges faced by couples involved in intercultural romances.

Scholarly reactions have captured the intricate dynamics of border-crossing romance, especially in terms of how 90 Day Fiancé portrays power dynamics between the U.S. citizen and their foreign partner. Previous research has argued that the show tends to dehumanize the foreign partners and frame the differences as rooted in cultural factors, such as ethnicity or nationality (Vesely, 2021). The show’s editing strategies have been discussed as fostering an atmosphere of suspicion towards the foreign partner, fueling xenophobic sentiments (Vesely, 2021). Furthermore, filming and interviewing friends and family of the U.S. citizen feeds concerns around the authenticity of the relationship, causing the latter to be viewed as a strategy to obtain a Green Card (Meszaros, 2018).

In Europe, especially Scandinavia, migration and integration have been central topics in public and media discourse for the past decade. The ‘immigration/refugee crisis’ of 2015 brought these issues to the forefront, influencing media reporting and political debates. Since then, representations of migration, integration, and social cohesion have also permeated popular culture and entertainment media, spanning dramas, comedies, and reality TV. However, research explicitly focusing on migration and integration within the context of entertainment is limited, while studies on media coverage of family/partner migration are rare and outdated (Hedman, Nygren, and Falhgren, 2009). Scholars have therefore emphasized the necessity for updated, empirically-grounded research examining the intersection of entertainment media and diverse migration forms (Eberl et al., 2018).

Interestingly, shows akin to 90 Day Fiancé have appeared in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark. In Norway and Denmark, the show in question is called ‘Love Beyond Borders’ (Kärlek Över Gränserna), while the respective Swedish production is called ‘Love Me, Love Me Not’ (Älskar, Älskar Inte). The latter, labeled by daily tabloid Aftonbladet as Sweden’s response to 90 Day Fiancé, focuses on partner migration in Sweden, exploring integration, assimilation, and various aspects of the migrant experience, from visa regulations to adapting to climate, cuisine, culture, and language, all accompanied by dramatic storylines.

Unlike 90 Day Fiancé, Älskar, Älskar Inte adopts a humanizing approach without relying on pity-inducing tactics. It presents individuals contemplating futures away from their homeland in a relatable manner, steering clear of common reality TV strategies like staged conflicts and tearful scenes. The show allows ample room for expressing frustrations about the weather, Swedish culture, food, and living costs, adding a critical dimension that empowers foreign partners to assert their agency. It highlights the option for them to return home if Sweden doesn’t suit them. Consequently, some foreign participants seem more like tourists than migrants, embodying a form of mobility associated with (more) choice and power.

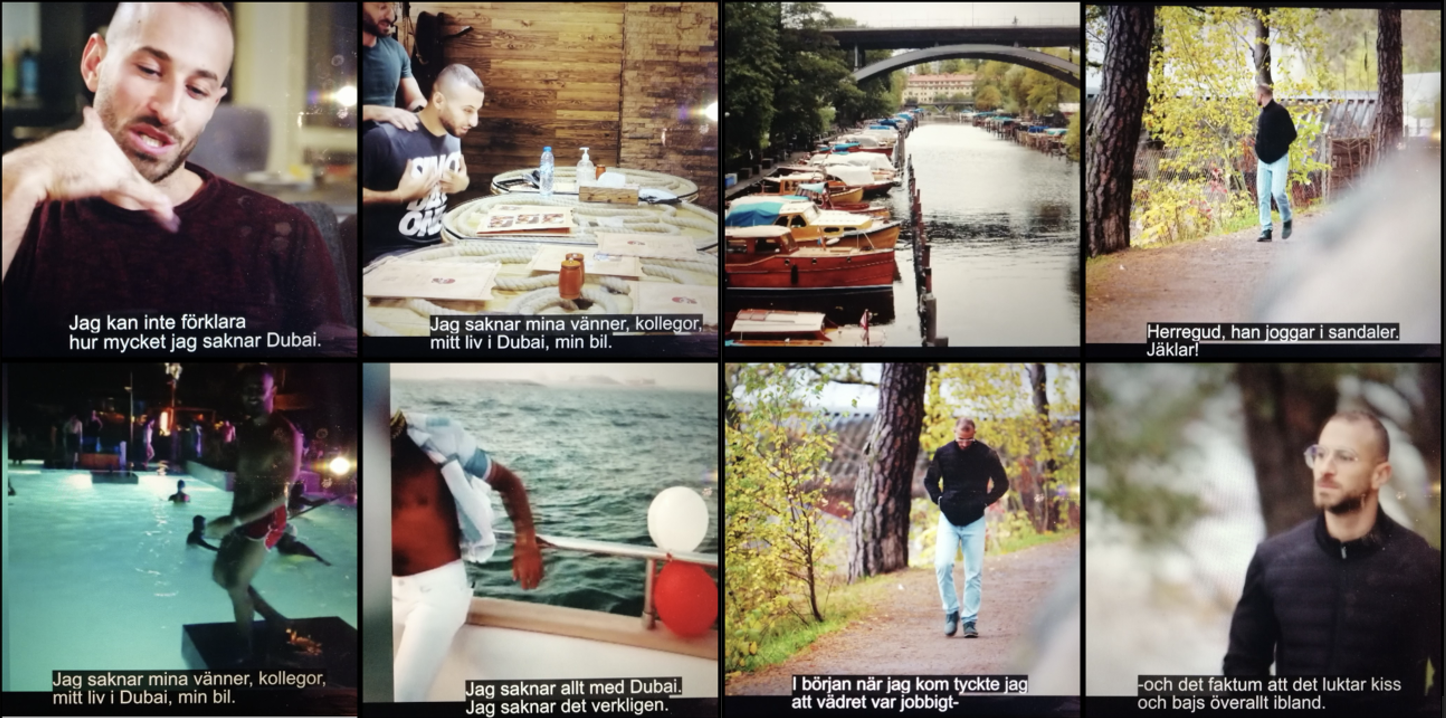

In season 2 of the show, the aforementioned representational strategy is evident in the story of Latif from Lebanon and Sabrina from Stockholm. Since arriving in Stockholm, Latif frequently contemplates returning to Dubai, where he lived and worked before coming to Sweden. In a confessional with a producer, Latif articulates his longing for his previous life – his posse, his car, his coquetries. These sentiments are further underscored by interspersed scenes captured through a smartphone, offering a glimpse into Latif’s vibrant life before relocating to Sweden. This lifestyle is contrasted starkly with his current existence in Sweden, which is marked by a more subdued and solitary atmosphere. Visually, this is registered by scenes where he strolls in Årsta Nature Reserve, in South Stockholm. Through a combination of voice-over narration and on-the-fly commentary, Latif narrates his experience as a love migrant: He finds the Swedes peculiar, noting their penchant for jogging in the rain wearing sandals; he despises the weather; he even observes a prevalent unpleasant odor of urine and feces in the area where he lives. Nevertheless, he expresses a commitment to exploring all that Sweden has to offer before deciding on his future.

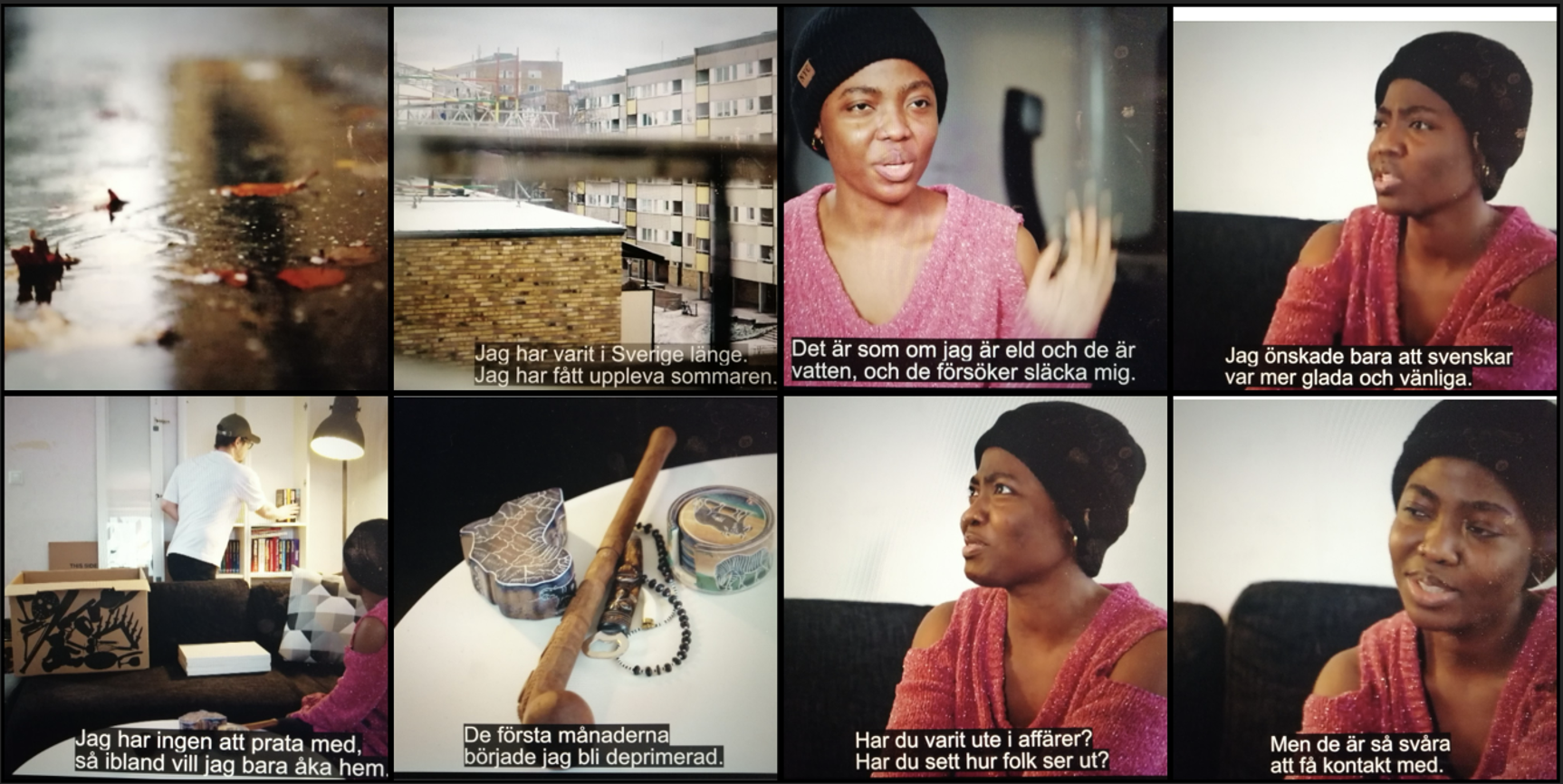

In the same season, one of the couples depicted is Rebecca from Nigeria and Micael from Kungsör. In a scene that blends the intimate, confessional format typical of reality TV with the portrayal of everyday activities, Rebecca explains that she misses her homeland and family and candidly expresses her dissatisfaction with various aspects of her new life. She discusses the social performance of Swedes as a factor preventing her integration, emphasizing the added difficulty when one doesn’t speak Swedish. She expresses a wish for Swedes to be more cheerful and approachable, noting that encounters at stores often lack friendliness. During a confessional, she describes feeling like fire with the Swedes acting as water, as if they are trying to extinguish her inner blaze. Rebecca’s insights shed light on a nuanced story of integration; it’s not solely a matter of an individual’s willingness and effort, but rather a two-way process taking place in ordinary encounters involving the local populations. Additionally, it is a long-term process that can take a toll on someone’s mental well-being, particularly if there is an increasing sense of dependence on their partner.

The final example comes from the third season of the show, featuring Viktor from Vetlanda and Caro from Nairobi. In an iconic scene, the couple visits the charming town of Gränna, a trip that provides ample opportunities for Caro to activate her tourist gaze, strolling through picturesque streets, enjoying Swedish candy, and attending a local celebration for the National Day where the Swedish national anthem is sung. Caro, not yet proficient in Swedish, turns to Viktor for an explanation of the lyrics and he clarifies that the song conveys the sentiment of desiring to live and ultimately pass away in the North. Caro looks at Viktor, clearly puzzled, and asks why. Viktor, failing to grasp her confusion, reiterates that these are the lyrics being sung. Caro then adds a touch of humor to the scene, asking, “Why would anyone want to live and die in the North? It’s cold” – emphasizing cultural disconnection as part of the migrant experience.

In closing, Älskar, Älskar Inte diverges from 90 Day Fiancé by granting foreign partners more agency and voice. The representation of love migrants varies, showing different levels of dependence and stakes. Humor, particularly in challenging and sometimes ridiculing Swedishness, plays a significant role. The Swedes are generally portrayed as less skeptical toward migration. It could also be argued that the show stands out for allowing considerable space for complaining about various aspects of life in Sweden, empowering foreign partners to explore their options, even rejecting Sweden. A comparison with the Danish and Norwegian counterparts could potentially uncover interesting shared tendencies or distinctions.

Broadly, addressing the central question of where ‘love migrants’ stand on the mobility continuum is crucial and entertainment television could be a powerful platform where such understandings are produced. Is this kind of mobility closer to the privileged mobility of tourists or the less privileged and less accepted mobility of immigrants, refugees, or asylum seekers? Exploring this further can contribute to a deeper understanding of how partner or family migrant mobility shapes world ordering, including dynamics of power and space.

Author’s note:

The author would like to thank the Centre for Geomedia Studies at Karlstad University, Sweden for financially supporting the overall research project, as well as her colleagues at Karlstad University, University of Gothenburg, and Jönköping University for commenting on this study’s preliminary findings.

Image Credits:

- The 90 Day Fiancé franchise (US, 2014-). Source: Author’s screenshot from Discovery+ Sweden.

- Scandinavian romance-based reality TV with a focus on ‘love migration’. Source: Author’s collage based on promotional material available at Discovery+ Sweden.

- The visual contrast between Latif’s playboy lifestyle in Dubai and subdued life in Sweden. Source: Author’s collage based on screenshots from Discovery+ Sweden.

- Rebecca complaining about Sweden and the Swedes: “It’s like I am fire and they are water, and they are trying to extinguish me”. Source: Author’s collage based on screenshots from Discovery+ Sweden.

- Caro looking puzzled by the lyrics of the Swedish national anthem – why would someone want to live and die in the North? Source: Author’s collage based on screenshots from Discovery+ Sweden.

Eberl, J.-M., Meltzer, C. E., Heidenreich, T., Herrero, B., Theorin, N., Lind, F., Berganza, R., Boomgaarden, H. G., Schemer, C., & Strömbäck, J. (2018) The European media discourse on immigration and its effects: A literature review. Annals of the International Communication Association, 42(3): 207–223.

Hedman, H., Nygren, L., & Fahlgren, S. (2009) Thai‐Swedish couples in the Swedish daily press – Discursive constitutions of “the Other”. NORA—Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research, 17(1): 34–47.

Meszaros J. (2018) Race, space, and agency in the international introduction industry: How American men perceive women’s agency in Colombia, Ukraine and the Philippines. Gender, Place & Culture 25(2): 268–287.

Vesely L. M. (2021) Media portrayals of binational couples in 90 Day Fiancé. Continuum 35(4): 571–584.