“Life in Plastic, It’s Fantastic”: Barbie, Gendered Expectations, and the Female-Driven Blockbuster

Courtney Brannon Donoghue / University of North Texas

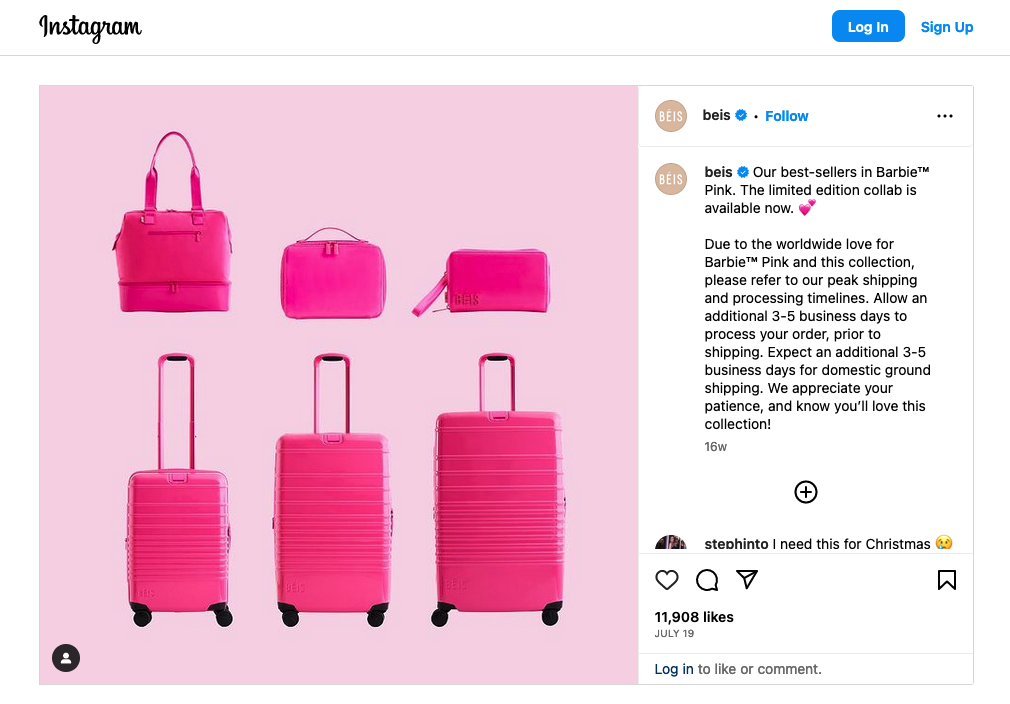

With the pink dust starting to settle from a record breaking box office summer, is now a good time to talk about Barbie? The Warner Bros. Mattel IP-driven tentpole made headlines for months after a strategic marketing rollout, strong ticket presales, and headline grabbing domestic and global theatrical returns. No matter your level of engagement or attention span this summer around the release of the female-driven blockbuster, you likely encountered Barbie’s reportedly $150 million marketing machine—internally called “Operation Barbie Summer”—costing nearly the same as the film’s production budget. The hot pink marketing campaign stretched across social media, press coverage, celebrity profiles and studio publicity, movie theater audiences, and brand partnerships from luggage to frozen yogurt. Walking into a Los Angeles theater on opening night, I witnessed a joyous crowd (a true four quadrant diverse audience) take pictures in the lobby, purchase collectible concession items, and fill the theater with a sea of Barbiecore inspired clothing and costumes.

In a traditional counterprogramming move, Warner Bros. scheduled Barbie to premiere the same weekend as Christopher Nolan’s Universal biopic Oppenheimer. Quickly deemed (and memed) across social media as “Barbenheimer,” the online fan-driven and unofficial double-feature experience drove both films to a massive domestic opening—around $162 million and $82 million, respectively. Barbenheimer premiered amidst a significant moment in Hollywood’s labor movement just as SAG-AFTRA joined the WGA in a labor strike.[1] As a result, any studio press or publicity activities could not include writers and actors from major studio releases. Trade press coverage framed the bigger than forecasted turnout for Barbie from the playful use of “legs” (an industry term to denote a longer than expected, profitable theatrical run) to zealously tracking box office milestones—Biggest opening weekend record for a female director! Highest grossing film release of the year (so far)! Biggest Warner Bros. global film release of all time! Highest grossing domestic release of all time by a female director!

As annual employment data studies like “The Celluloid Ceiling Report” illustrate, the disproportionate number of women working in above-the-line positions is astounding—women held 18 percent of directing, 19 percent of writing, and 31 percent of creative producing jobs on the top grossing 250 Hollywood films in 2022.[2] As a studio project with women in the majority of above-the-line roles, Barbie reflects one of the few female-driven tentpoles released in recent years. Writer-director Greta Gerwig’s leap to helming a blockbuster (co-penned with her partner Noah Baumbach) marks a continued ascent from personal, independent stories (Frances Ha, Lady Bird) to mid-budget prestige dramas (Little Women). As part of the small A-list class of studio star-producers with overall deals, Margot Robbie developed and co-produced the project under her company LuckyChap Entertainment. In many ways, both pre- and post-Barbie, the access, opportunities, and network to build a sustainable career make both Gerwig and Robbie outliers. Due to decades of ingrained gender inequity impacting how women are hired and promoted in above-the-line work, Gerwig’s career trajectory is not accessible to most of her peers, particularly for women of color who make up less than 2 percent of studio directors.[3]

Even amidst current studio production slates increasingly dominated by comic book, video game, and toy franchises, Barbie isn’t just any media property.[4] Created in 1959 by Mattel co-founder Ruth Handler, Barbie is a doll whose legacy carries heavy baggage for many girls and women around the world from joy and nostalgia to pain and rejection. Followed by a wave of 2010s media coverage, Mattel expanded the toy line beyond the stereotypical doll to offer more inclusive and diverse representations. On the one hand, the corporate-driven overhaul emerged from a time when sales were down and a new celebration (to use Mattel’s language) of the “power of representation” merely served to project a more modern, palatable rebranding of the polemical doll with different body shapes and heights, skin tones, hair textures, and disabilities. In Gerwig’s cinematic Barbie Land, the reality that anyone can be Barbie stems directly from the company’s twenty-first-century branding overhaul. Robbie stars in the title role as the “stereotypical” white, thin CIS-gender blonde with a somewhat more diverse ensemble of Barbies—including Issa Rae, Kate McKinnon, Alexandra Shipp, Emma Mackey, Hari Nef, Sharon Rooney, and Ana Cruz Kayne—or what one film critic called a “multicultural Barbiarchy.” Oh, and a multitude of Kens led by Ryan Gosling, Simu Liu, Kingsley Ben-Adir, and others show up too.

On the other hand, Barbie as a toy, as a brand, as an icon of childhood, and as an idealized marker of “she can be anything” womanhood functions as a mirror reflecting our society’s constructed gender identities, expressions, and expectations for women and girls. Gerwig stated in a New York Times Magazine interview “things can be both/and. I’m doing the thing and subverting the thing [with Barbie]”.[5] In trying to address politics at the structural level and nostalgia at the personal level, the film attempts to engage with and tackle the complicated legacy and contradictions of Barbie, most notably the multiple endings. Yet, in invoking the toppling of the patriarchy to pink feminism to representation matters as simplified signifiers with even simpler narrative resolutions, Barbie falls for Hollywood’s reliance on what Kristen J. Warner calls “plastic representation.”[6]

In my new book—The Value Gap: Female-Driven Films from Pitch to Premiere (2023, University of Texas Press)—I explore the multi-layered experiences of women writers, producers, and directors in the 2010s navigating Hollywood production and distribution cultures.[7] At each stage of the filmmaking process, from development to distribution, film projects by and for women face gendered expectations and limitations around their value, viability, capability, and overall perceived worth within a male-dominated media business. Female-driven stories and their female-targeted audiences routinely have been dismissed for “having no value” within Hollywood studios and the marketplace. As I argue in The Value Gap, risk in the film business is never measured equitably nor shared evenly, often breaking down along gendered and racialized lines. Industry lore long circulated in the film business—“women don’t go to the movies!”, “female-led movies don’t make money!”, and “female directors don’t have the experience (or desire) to direct big budget action blockbusters!”—operates to explain structural gender inequities and serves to reinforce and normalize studios prioritizing the male-driven status quo.

An all-too-familiar narrative circulated prior to Barbie’s release across trade press coverage, interviews, and publicity focusing on the female-driven blockbuster as a risky endeavor. Gerwig joked in a 2022 interview that Barbie “could be a career-ender,” a comment industry journalists and the trade press pounced on and circulated widely.[8] A risk to Gerwig’s career, a risk for Robbie’s bankability, a risk for Warner Bros. and its newly reorganized parent company Warner Bros. Discovery, a risk for Mattel and its new film division, and a risk for struggling movie theaters. Yes, Barbie was a potential risk for all involved (the case with most expensive tentpoles) but Barbie was also too big to fail for the women involved.

Each time a female-driven film proves to be a financial success, the film immediately takes on the impossible weight of carrying the future of female filmmakers, female-driven projects, the major studio, the movie theater business, and the entire US economy! One of the most striking examples of gendered expectations appeared in a Los Angeles Times editorial declaring Barbie “a billion-dollar milestone for women in Hollywood” and highlighted the female-driven hit “showed the world that women directors can make blockbusters.” [9] How in the year of 2023 is Barbie the first indication or evidence that women can make blockbusters?! Looking back more than a decade, as I discuss in The Value Gap, similar gendered valuation circulated around the risk and recognition of female-driven hits from Twilight (2008) to Wonder Woman (2017).[10] Too often female-driven success was framed as an exception, a one-off triumph of hard-fought gains too quickly forgotten. Once the emergence of another female-driven blockbuster, and women’s value at the box office is re-discovered, the cycle begins again, what I call the “amnesia loop.”

Whatever your feelings about Barbie as an example of powerful women ruling popular culture, Hollywood’s short-sighted tendency towards plastic representation, a contradictory lesson in popular feminism, or a corporate-driven pink fever dream, Barbie is an undeniable and unprecedented commercial hit made by and for women. And yet, because of Hollywood’s faulty memory for women’s success, and for valuing their work and experiences, the question remains what lessons will Hollywood learn and what the major studios will remember from Barbie’s successful global release beyond the plastic ones.

Image Credits:

- Barbie in Barbie Land. Source: Author’s screenshot from the Warner Bros. trailer.

- Example of a Barbie brand partnership with Béis luggage. Source: Author’s screenshot.

- Mattel’s “We Are Barbie” diversity language. Source: Author’s screenshot from Mattel’s website.

- New York Times Magazine Greta Gerwig Barbie profile. Source: Author’s screenshot from NYT.

- Example of discourse around Barbie as a record-breaking female-driven film. Source: Author’s screenshot from Twitter/X.

- Miranda Banks and Kate Fortmueller, “Unity will determine if the Hollywood writers strike is successful,” The Washington Post, June 22, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/made-by-history/2023/06/22/wga-strike-hollywood-unions-solidarity/. [↩]

- Martha M. Lauzen, “The Celluloid Ceiling: Employment of Behind-the-Scenes Women on Top Grossing U.S. Films in 2022” https://womenintvfilm.sdsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/2022-celluloid-ceiling-report.pdf. [↩]

- Stacy L. Smith, Katherine Pieper, and Sam Wheeler, “Inclusion in the Director’s Chair: Analysis of Director Gender and Race/Ethnicity Across the 1,600 Top Films from 2007 to 2022,” USC Annenberg Inclusion Initiative, January 2023, https://assets.uscannenberg.org/docs/aii-inclusion-directors-2023.pdf. [↩]

- The film is not only IP-driven but IP-dependent on Mattel’s participation, specifically their new film division, Mattel Films. The company has long held big ambitions for Barbie across various media iterations—Barbie and the Rockers: Out of This World (1987) television special to home video release, animated straight-to-DVD movies, numerous videogames, and multiple Netflix animated series. As early as the 2000s, Mattel reportedly tried to develop a live action, feature film with various studios (Universal, Sony) and creative talent (Diablo Cody, Amy Schumer, Anne Hathaway) attached at different points; James Hibberd, “Barbie Had a Long Hard Road to the Big Screen,” The Hollywood Reporter, July 21, 2023, https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-news/barbie-rejected-movie-ideas-1235541234/. [↩]

- Willa Paskin, “Greta Gerwig’s Barbie Dream Job,” New York Times Magazine, July 11, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/11/magazine/greta-gerwig-barbie.html. [↩]

- Kristen J. Warner, “In the Time of Plastic Representation,” Film Quarterly, Vol. 71, Number 2 (2017), pp. 32–37. [↩]

- Courtney Brannon Donoghue, The Value Gap: Female-Driven Films from Pitch to Premiere (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2023). [↩]

- Dua Lipa: At Your Service podcast, Interview with Greta Gerwig, November 25, 2022, https://www.service95.com/dua-lipa-at-your-service/; Ryan Gajewski, “Greta Gerwig Says She Worried That Barbie Could Be Her ‘Career-Ender,’” The Hollywood Reporter, November 25, 2022, https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-news/greta-gerwig-barbie-career-ender-1235269803/. [↩]

- The Times Editorial Board, “Barbie is a billion-dollar milestone for women in Hollywood,” August 8, 2023, https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2023-08-08/editorial-a-milestone-for-women-in-hollywood [↩]

- Courtney Brannon Donoghue, “Gendered expectations for female-driven films: risk and rescue narratives around Warner Bros.’ Wonder Woman,” Feminist Media Studies, Vol. 22, Number 3, (2019): pp. 485-501. [↩]

thank you for share with us.

So beautiful!