Formatting the Real

J.D. Swerzenski and Brendan McCauley/ University of Mary Washington and University of Massachusetts-Amherst

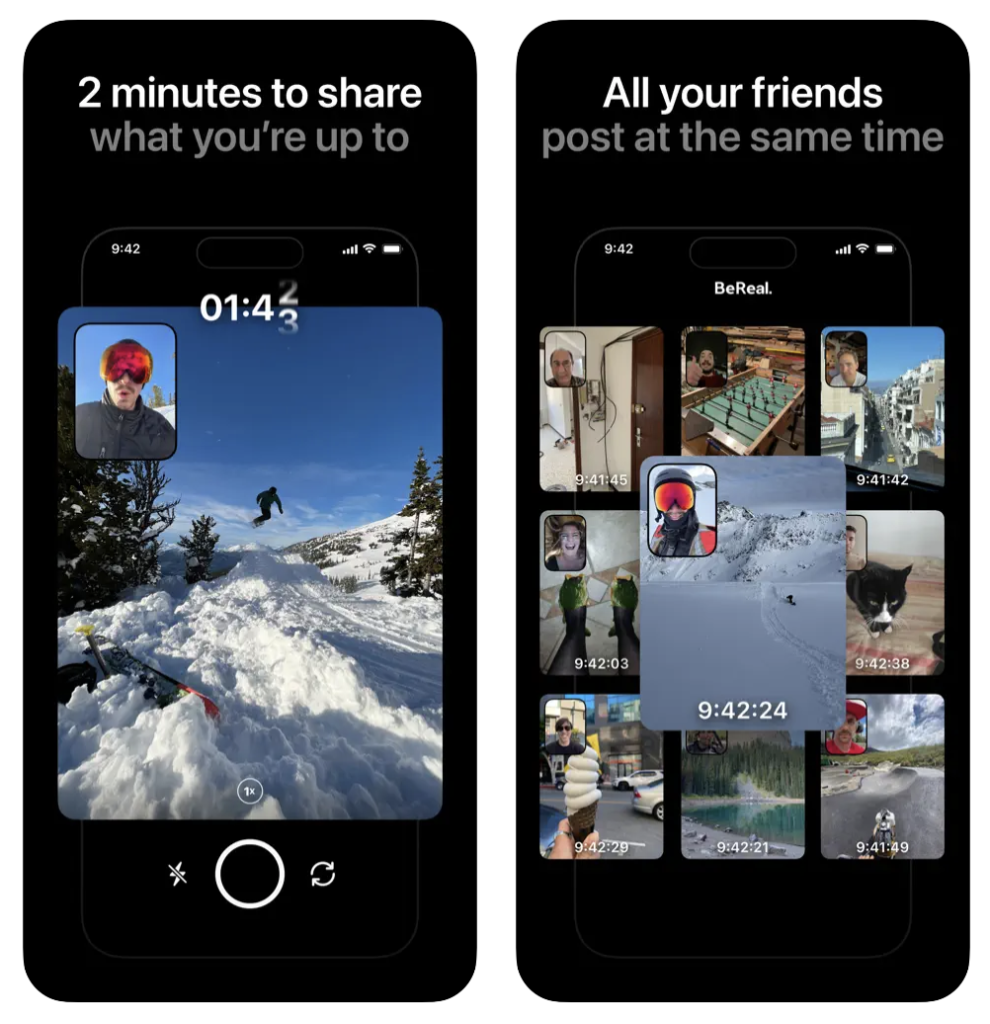

Shortly after its 2019 debut, the social media app BeReal uploaded an ad to YouTube outlining its ethos. Atop shots of dead-eyed twenty-somethings scrolling their news feeds and photo filter options, the onscreen text prompts: “What if social media were different from this?” What makes BeReal “different” from other platforms follows next: “no likes, no followers, no ads, no bullshit.” More notable than these restrictions was the app’s key affordance, outlined in the subsequent text: “Once a day, at a random time, you have two minutes to capture and share”. That one shared post is a photo, specifically two inlaid photos using the smartphone’s front and back facing cameras, typically capturing the user’s selfie with the front camera and their location with the back.

In the years since the release of that ad, BeReal has experienced a surge in popularity, garnering over 70 million downloads and receiving Apple’s app of the year award for 2022. Beyond this momentary market success, the app has introduced a particularly sticky conception of “realness” in social media spaces. Nowhere is this impact more visible than in the signature visual format of its outputs: that small portrait of a person inset into a larger image of a landscape. We argue that this visual format and the traction it has gained as a signifier for “realness” is BeReal’s most significant cultural impact, one which now lives beyond the app and will likely outlive the app itself.

Realness in BeReal is rendered through a two-step process, with the subject first documenting themselves through the inset front camera image, then locating their body in a specific space via the back camera. Unlike the typical subject/backdrop positioning of traditional photos, the BeReal format reorients the image so that we now see what the subject sees alongside them. Through the act of looking at the photo, we replicate the subject’s own looking as a way of being in the world. This visual format further creates its “reality stamp” by directly indexing a smartphone’s forward and rear-facing camera lenses as a type of dual authentication measure. It puts a particular person “in” a particular place at a particular time. Rather than only presenting a carefully curated “frontstage” image–such as one might do on Instagram–BeReal users expose the “backstage” area of the photo where construction and manipulation may occur (Larsen, 2005). This performance of transparency as visual verification is meant to characterize the user as being in a type of “real moment”.

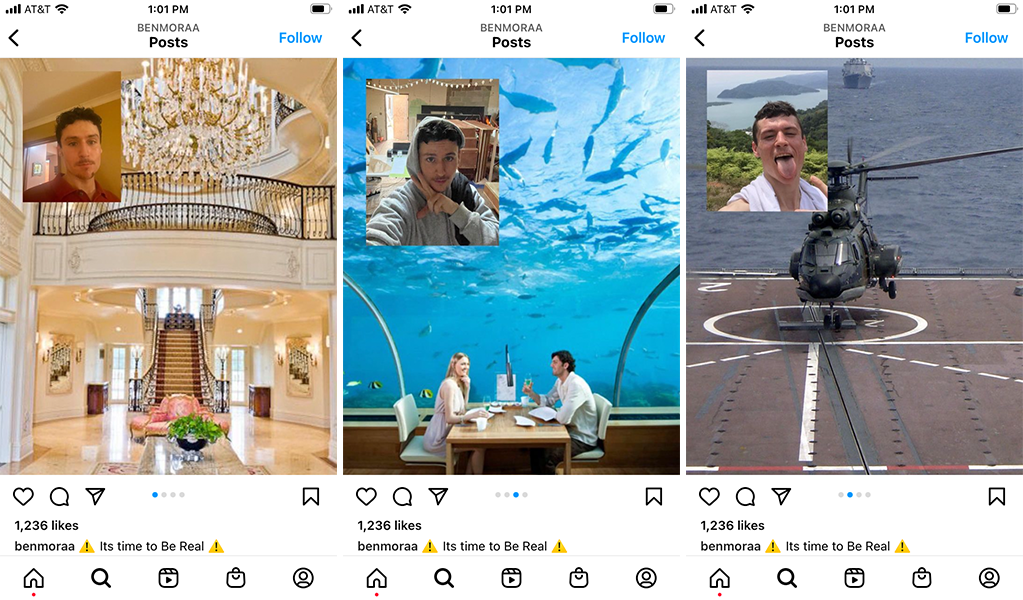

This visual structure of two inset images also creates an inherent narrative structure that converts any content within it into a story about a kind of person in a kind of place. This juxtaposition in turn produces a secondary meaning inferred from the relation between the two images. As a structure of meaning that imparts the cultural value of “authenticity” to the stories told through it, this format employs the same “hypersignification” that is characteristic of meme genres (Shifman, 2014). By highlighting the construction and staging of both front and back images, the “code” of what makes a moment real is itself on display as an operable sign. Yet in reading the resulting images as intended from the top left as “image 1 + image 2 = punchline”, the very same formatting code that constructs reality may be used to undo or critique it both on and off the app. This meme-ability has opened the BeReal format up to distribution across other discourses and platforms. Its adoption as an operable sign across online cultures allows anyone to treat “being real” just another mode of online self presentation. Instagram user @benmoraa, for example, has used the format to “place” himself within a range of unlikely locations: decadent McMansions, the deck of an aircraft carrier, underwater restaurants, etc.

That these images were posted along with the caption ”time to be real” to his Instagram account acts as a meta-level of critique of the platform. The verifiability of BeReal’s picture-in-picture format is undermined by its shoddy re-construction, with the subject here placing himself in a space he clearly isn’t in. These instances not only create humor through disjunction, but subsume it back into an “Internet ugly aesthetic” that characterizes the precarious relationship between users and any form of authenticity online (Douglass, 2014).

@benmoraa’s BeReal meme speaks to a fundamental issue with BeReal’s conception of reality. The app does not in fact verify reality, but produces one: absorbing both sides of a spatial relationship with a smartphone’s screen into the format of the screen itself. Importantly, this method of producing reality means that what is captured in and asserted by any BeReal “moment” is the positioning of a smartphone in a specific time and place – not a person. It is important then to consider the centrality of what BeReal’s reality formatting omits. The superimposition of one image onto another one hides the object that lies between them: the user’s smartphone. The phone need not be seen because it is always presumed. More so than preceding photo-based social media apps, BeReal takes the smartphone for granted as ubiquitous: the only way through which the world is experienced, distributed, and interpreted.

What occurs in the visual formatting by the BeReal app and the creative memes of those who humorously critique it is the production of reality as a relationship with smartphone screens. On display across all of BeReal’s outputs is its user’s attachment to a device that stands in between them and of the mediated world that it places them into. There is nothing on exhibit in these images—no other reality—outside of this attachment that we can see. As a conveyed spatial relationship—between the smaller image and the larger one—there is an implied touch in the place of a real one, what Marks (1998) calls a haptic visuality that elicits a tactile presence between the touch of these two frames. However in all cases what is actually being touched– physically held by a hand–is a smartphone. This is true both in the moment captured by the photograph and for the moment in which a viewer encounters it. What ultimately distinguishes BeReal from other image apps is not its rejection of their particular affordances, but rather its full embrace of the smartphone as a medium and as the primary way of relating to the world.

As Light et al. (2018) remind: “Apps matter because they reflect our cultural values.” To this end, BeReal’s impact will likely be felt less by whether it will be able to offer an effective challenge to Instagram in the future than through what it says about our cultural perception of reality. As the app’s success has shown, the idea of presenting our real selves on social media is clearly an alluring one, which points in turn to a larger dissatisfaction with the stake of social media on Instagram and other established platforms. Yet more significantly, BeReal shows how our contemporary conception of “real” is always already produced by and for screens. Neither the BeReal platform nor the users posting on it can visualize any world that is not built through the affordances of a smartphone. The encoding of this particular type of reality as “being real” can then only mark any visuality outside of it as “not”.

Image Credits:

- BeReal’s 2020 promotional video “Just your Friends, for Real.” on YouTube.

- Screenshot image taken from BeReal’s Apple App Store Page.

- BenMoraa’s BeReal parody posts on Instagram.

References:

Douglas, N. (2014). It’s supposed to look like shit: The Internet ugly aesthetic. Journal of visual

culture, 13(3), 314-339.

Larsen, J. (2005). Families seen sightseeing: Performativity of tourist photography. Space and

culture, 8(4), 416-434.

Light, B., Burgess, J., & Duguay, S. (2018). The walkthrough method: An approach to the study

of apps. New media & society, 20(3), 881-900.

Marks, L. U. (1998). Video haptics and erotics. Screen, 39(4), 331-348.

Shifman, L. (2014). The cultural logic of photo-based meme genres. Journal of visual culture,

13(3), 340-358.