The Great Society, Data Privacy, and the Law of Unintended Consequences

Jennifer holt / University of California, Santa Barbara

When considering where the locus of control over our personal data and individual privacy lies, our first thoughts should be about Big Tech and corporate Terms of Service agreements that force users to consent to a host of rights infringements as the price of access. Their platforms have normalized privacy violations and a culture of what Shoshanna Zuboff has termed “surveillance capitalism” [1] to such an extent that a privatized form of informal policy largely dictates our digital civil liberties. This was a development many decades in the making. In fact, it can be traced back to the beginnings of computerized databases in the 1960s and a cultural fear of centralized, state control weaponized by digital technology.

The U.S. government’s concern for the privacy of its citizens peaked in the 1960s. Portable recording technologies and computing began to sound regulatory alarms as their capabilities elicited new threats to privacy rights. Such worries were amplified by the Supreme Court, as Chief Justice Earl Warren stated in a 1963 opinion regarding recording devices and entrapment, “[T]he fantastic advances in the field of electronic communication constitute a great danger to the privacy of the individual…”[2] There was also a wave of writing by scholars and journalists at this time that focused on technology, privacy, and personal autonomy which helped inform public debate. In many ways this work anticipated current anxieties about the price of life under Big Tech. Vance Packard’s The Naked Society (1964), Alan F. Westin’s Privacy and Freedom (1967), and Arthur Miller’s The Assault on Privacy (1971) were among the most influential in this genre.

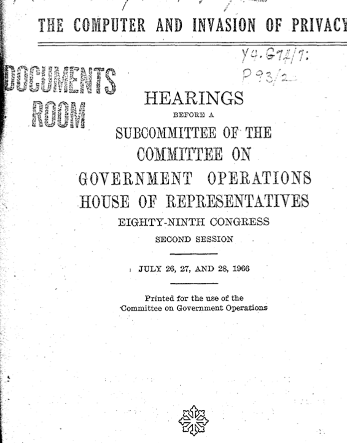

This was the context in which President Johnson proposed a federally-controlled data center called the “National Data Bank” in 1965 as part of the Great Society project. The data center was imagined as a tool for efficiency and organization that would consolidate federal databases at the dawn of computerized record-keeping. A special Congressional subcommittee on the Invasion of Privacy was established in the House of Representatives as a result. Four separate hearings were held in the House and Senate between 1966-1967 to discuss the threats to privacy posed by the computer and government control of data. They were dominated by overwhelming expressions of concern about the sanctity of individual privacy and civil liberties, with the state – aided by the yet unknown capabilities of digital technology – seen as the main potential threat.

The Invasion of Privacy Subcommittee Chair running the House hearings, Representative Cornelius Gallagher (D-NJ), introduced the investigation of the National Data Center in July, 1966 by saying, “The possible future storage and regrouping of such personal information…strikes at the core of our Judeo-Christian concept of ‘forgive and forget,’ because the computer neither forgives nor forgets.”[3] Frank Horton (R, NY) warned that “the magnitude of the problem we now confront is akin to the changes wrought in our national life with the dawning of the nuclear age… it is not enough to say ‘It can’t happen here’; our grandfathers said that about television.”[4] One of the original Internet architects, Paul Baran, alluded to threats posed by the future cloud in his testimony, noting that “A multiplicity of large, remote-access computer systems, if interconnected, can pose the danger of loss of the individual’s right to privacy – as we know it today.”[5] In his expert witness statement, author Vance Packard noted the “hazard of permitting so much power to rest in the hands of the people in a position to push computer buttons….[because] we all to some extent fall under the control of the machine’s managers.”[6]

Gallagher had a remarkably prescient grasp of our current predicament, even back in 1967.[7] His speech to the American Bar Association that year entitled “Technology and Freedom” was quite striking in its predictive accuracy. He warned, “Although the technology of computerization has raised new horizons of progress, it also brings with it grave dangers…the computer, with its insatiable appetite for information, its image of infallibility, its inability to forget anything that has been put into it, may become the heart of a surveillance system that will turn society into a transparent world in which our home, our finances, our associations, our mental and physical condition are laid bare to the most casual observer. If information is power, then real power and its inherent threat to the Republic will not rest in some elected officials or Army generals, but in a few overzealous members of a bureaucratic elite.”[8]

The final report from the House Committee was clear about the links between data privacy and democracy: “A suffocating sense of surveillance, represented by instantaneously retrievable, derogatory or noncontextual data, is not an atmosphere in which freedom can long survive…This report, therefore, charges the Federal Government as well as the computer community with a dual responsibility….they must….guarantee Americans that the tonic of high speed information handling does not contain a toxic which will kill privacy.”[9] The report further noted that “a grave threat to the constitutional guarantees exists in the National Data Bank concept,” leading to their ultimate recommendation to abandon it until privacy protections were fully explored and guaranteed “to the greatest extent possible to the citizens whose personal records would form its information base.”[10]

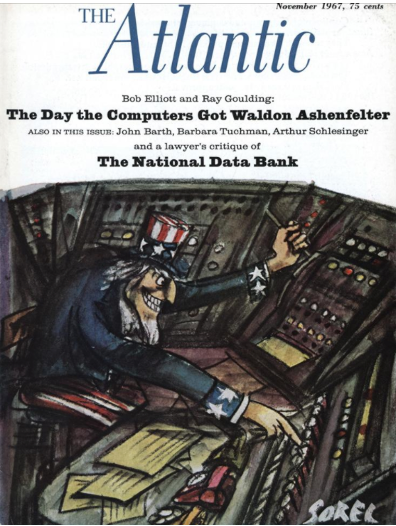

At the same time, the reporting in the popular press was highly alarmist. One representative article in Look magazine entitled “The Computer Data Bank: Will it Kill Your Freedom?” posed various questions that could easily be answered by “any snooper with a computer,” such as: “Did your sister have an illegitimate baby when she was 15? Did you fail math in junior high? Are you divorced or living in a common-law relationship? Do you pay your bills promptly? Are you willing to talk to salesmen? Have you been treated for a venereal disease? Are you visiting a psychiatrist? Were you ever arrested?”[11] The public response to these developments led to the end of all discussion about a National Data Bank by 1970.

Sadly, it would be a pyrrhic victory. The focus on protecting public data from the perceived dangers of centralized state collection and storage blinded legislators to the problems created by the alternative: putting data in the hands of private companies. Corporations ultimately filled the vacuum created by the National Data Bank’s failure, and became the chief custodians of American citizens’ private data. In Congress’s attempt to defend US citizens from experiencing a version of “1984” and “Big Brother” which were mentioned relentlessly during the hearings, they ended up creating exactly what they were trying to avoid, albeit serving a different master. I am not suggesting that government control over public data is preferable, but our current experience of private control without regulatory oversight has proven disastrous for individual and collective privacy. To his credit, Senator Long (D-MO) who presided over the Senate hearings in 1966 and 1967 did warn that if the proposals for a National Data Bank “concerned themselves only with Government interests, and if individual, private interests were ignored, we might be creating a form of Frankenstein monster”[12] but his words went unheeded. Unfortunately, history would prove him right.

Image Credits:

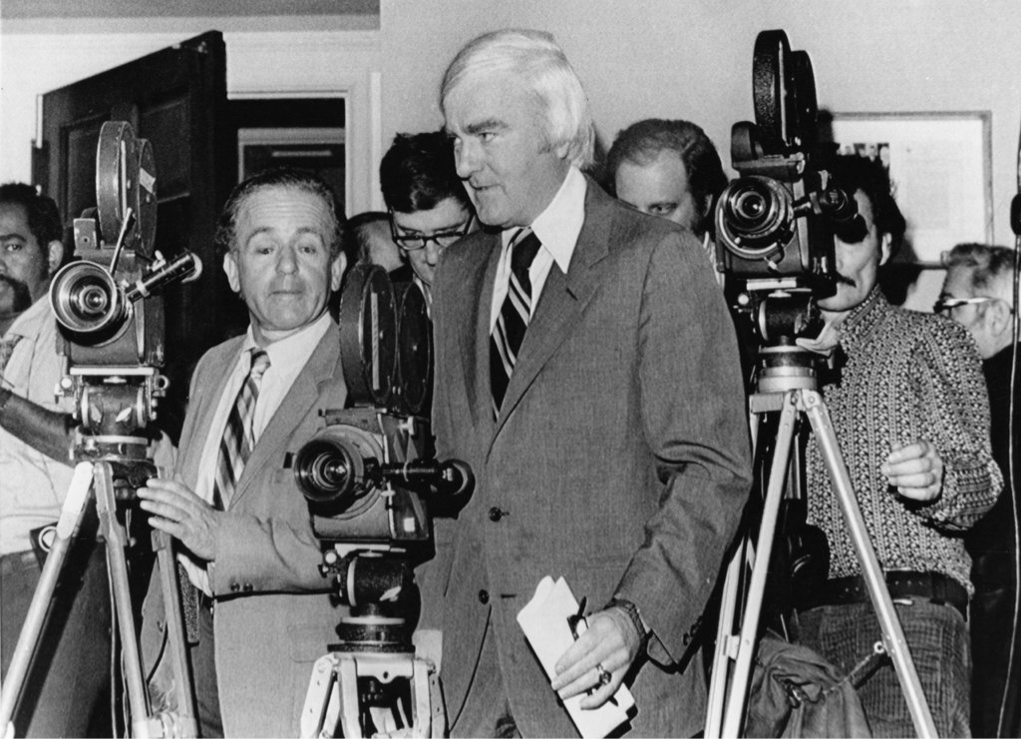

- Representative Cornelius “Neil” Gallagher, 1972. New York Times.

- Computer and Invasion of Privacy Hearings Document, 1966. Credit: “Congressional Special Subcommittee Holds Hearings on the Computer and Invasion of Privacy (PDF).” (author’s personal collection)

- Cover of The Atlantic November, 1967.

- Zuboff, Shoshana. 2020. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. First Trade Paperback Edition. New York: PublicAffairs. [↩]

- Chief Justice Warren, Concurring Opinion, Lopez v. United States, 373 U.S. 427, 441 (1963). https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/373/427/#tab-opinion-1944364 [↩]

- “The Computer and Invasion of Privacy,” Hearings before the Special Subcommittee on Invasion of Privacy, House Committee on Government Operations, 89th Cong., July 26, 1966. P. 3. [↩]

- Ibid, Pp. 5-6. [↩]

- Ibid, p. 125. [↩]

- Vance Packard Testimony, House of Representative Hearings on “The Computer and Invasion of Privacy,” July 26, 1966, Pp. 11-12. [↩]

- This could be from his many years of being persecuted and having his own privacy violated by J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI. See Ron Felber, The Privacy War, Montvale, NY: Croce Publishing, 2003. [↩]

- Quoted in Felber, P. 176. Also see the statement of Professor Arthur R. Miller, “Computer Privacy,” Hearings before the Subcommittee on Administrative Practice and Procedure, Senate Committee on the Judiciary, 90th Cong., March 14, 1967. Pp. 72-73. [↩]

- U.S. Congress, House Committee on Government Operations, “Privacy and the National Data Bank Concept,” July, 1968. P. X. [↩]

- Ibid, p. 6. [↩]

- Jack Star, “The Computer Data Bank: Will it Kill Your Freedom?” Look, June, 1968. P. 27. [↩]

- “Computer Privacy,” Senate Hearings, P. 1. [↩]