Is Everyone Where They Should Be? Safety, Surveillance, and Diverse Students

Elizabeth Ellcessor / University of Virginia

Campus safety has been a hot topic for nearly forty years, as colleges and universities increasingly attempt to address the health, safety, and wellbeing of residential, traditional-aged students. Initially, these efforts were tied both to the need to improve pedestrian safety and to fears of sexual assault, leading to an exponential rise in blue light emergency phones. These place-bound media marked a campus a geography of ostensible safety, even though they were rarely used and generally ill-suited to addressing sexual assault, in particular (Rentschler 2003; Fisher, Daigle, and Cullen 2009). A mainstay of campus tours, today’s blue light phones are often repurposed to host multiple other emergency media systems—sirens, loudspeakers, message displays—on top of their original features.

In my recent book, In Case of Emergency: How Technologies Mediate Crisis and Normalize Inequality (New York University Press, 2022), I consider these phones alongside a range of campus safety technologies as examples of “emergency media.” These are the media technologies and systems that inform us of emergencies, allow us to inform others, and connect people to systems of aid. Ultimately, I argue that emergency media are complicit in defining emergency in opposition to normalcy, a binary that 1) prevents institutions from seeing emergencies that befall marginalized people or communities and 2) works against providing ongoing care and support. To change—not merely update—emergency media, we must look to where and how emergency is understood differently.

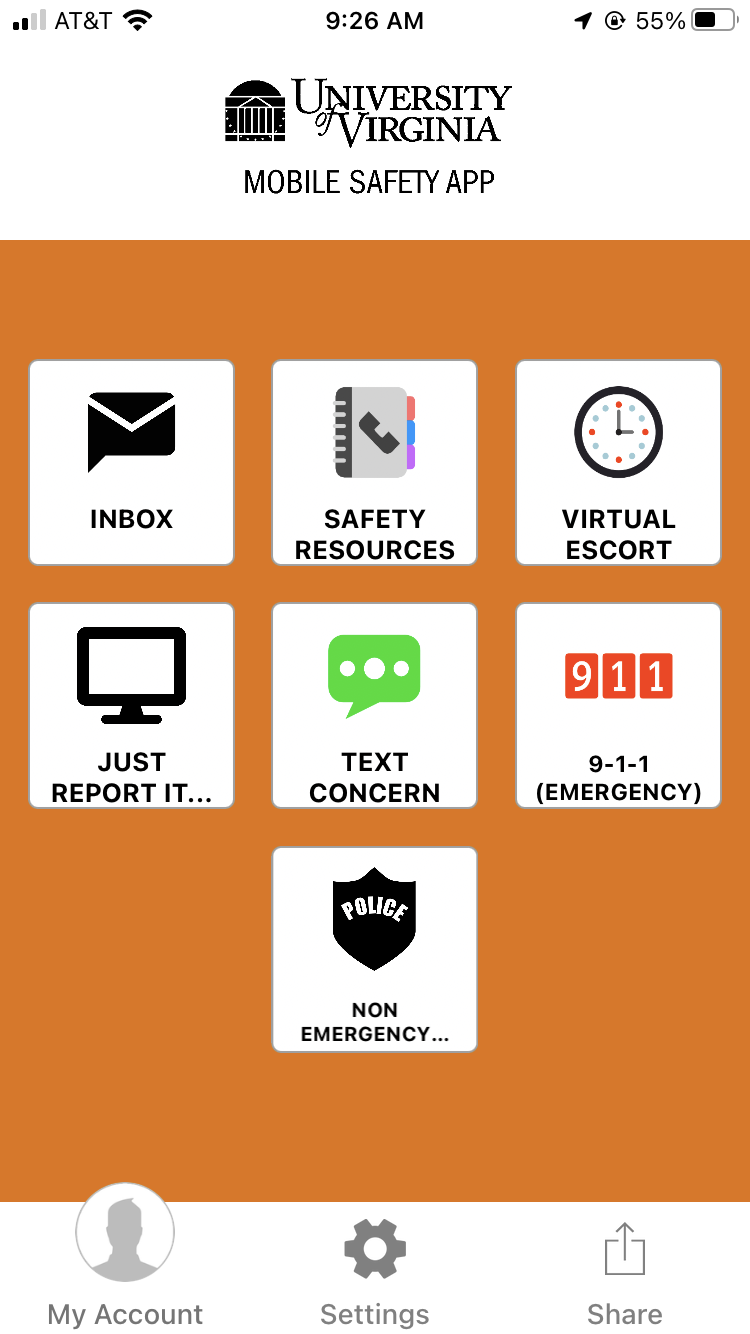

On campus, as elsewhere, the newest mediation of safety and emergency is the smartphone app (Glover-Rijkse et al. 2020). Often run on platforms provided by third parties, such as Rave Guardian or LiveSafe, these apps remediate older emergency media, such as 911 and blue light phones, and attempt to centralize a host of other resources, including information about reporting hate crimes, mental health support resources, and so on.

Yet despite the plenitude of official emergency media available, these are not the media systems that students use to ensure their own safety or that of those around them. In 2019-2020, several colleagues and I undertook a project at the University of Virginia to understand the relationship between students’ perceptions of safety and their mobile technology use. We held six focus groups and conducted several supplemental interviews. In these conversations, young adults described using Apple’s Find My, as well as family apps such as Life360, the mapping features of Snapchat and Facebook Messenger, and location-tagged Instagram posts. All of these services are technologically-enabled forms of social and geographical “safety surveillance,” allowing students to watch one another and infer safety or risk from various locations. If blue light phones tied safety to a geographical region, these uses of digital media tie safety to individuals’ locations and infer emergency or risk from seeing people in the “wrong” places.

Many students discussed location sharing as routine, sharing locations with family, friends, roommates, significant others, and members of shared religious, ethnic, or extracurricular communities. For instance, Ella, a white first year student, explained that she and her friends would turn on location sharing so that after a night out they could look “to make sure that everyone’s on the map. So at the end of the night you can be like, ‘Okay, everyone’s in their dorms. There’s no one, like, far away in a river.’” Such descriptions, though flippant, indicate that for some students the primary risks were relatively rare ones, such as abduction, rather than the more common crimes of sexual assault, car theft, or aggravated assault. High-profile disappearances, abductions, or deaths drove such discussions, especially among white female students, as these cases notably increased their parents’ concerns for their safety.

Many decisions about campus safety and the emergency media that support it have been driven by the perception of female students, particularly white female students, as particularly at-risk. This perception is strong and not unfounded, given that nearly half of all campus crimes in recent years were sexual offenses, primarily committed against women. However, responses to this threat, such as increased campus policing, do not serve all students equally; campus policing routinely targets Black men and reduces their feelings of belonging or safety (Dizon 2021). Thus, the ecosystem of campus safety is one in which perceived risks to some normative students cause institutional and technological changes that may not serve (and may actually harm) marginalized students.

Given this discrepancy, the use of media for safety surveillance looked different among students who did not feel well served by existing safety infrastructures. Students who identified as members of minority groups, including queer students, more regularly framed location sharing as a matter of care for their community. Members of close-knit communities, such as campus ethnic and religious clubs, described routinely activating locative services to be sure that they could check up on and potentially protect younger students. Location tracking worked well for this, in part, because students had strong beliefs about what were typical, or safe, spaces for them and what white-dominated spaces might be riskier or more hostile. Rather than finding safety through official emergency media systems, members of minority groups found that their sense of safety relied on “the sense of community we’ve had to really create for ourselves.” Location sharing was one way that those community bonds were expressed.

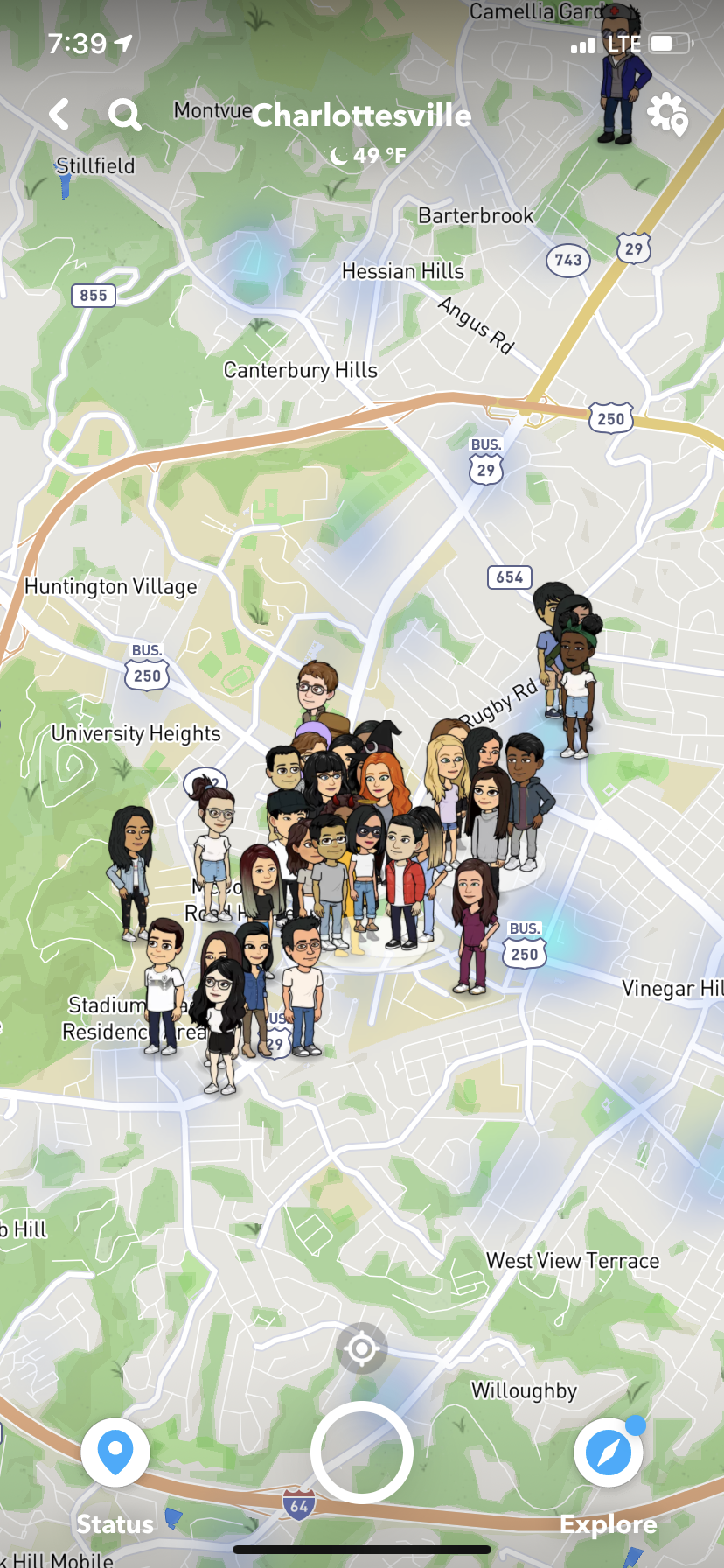

Furthermore, while most students talked about safety surveillance from the perspective of watching others, some students from marginalized groups discussed how they used these media to reassure themselves of their own safety. One interviewee—Roxane, a Muslim woman who wore hijab—explained that she only began using SnapChat maps to observe her friends after coming to college, but that she appreciated being able to see who was around in her neighborhood because “it makes me feel safe, too, if I see more of my friends around the area.” Just as safety surveillance provided reassurance of others’ safety, so it allowed her to reassure herself by mapping out where she was among friends and could feel safe at an institution where she was a highly visible member of a minority group.

While the media technologies have changed, the central purpose of most campus emergency media systems remains the cultivation of a feeling of safety, aimed particularly at white women and their parents. By contrast, the uses of surveillant commercial technologies by other students can reflect very different understandings of what constitutes “safety” or “emergency.” In these community-driven uses of media as systems of care, students elevate the risks of racism, harassment, or hate crime to the status of emergencies, as deserving of attention as more familiar matters of campus safety. If these were the core problem at hand, we might ask, how would campus safety infrastructures and emergency media work differently?

With thanks to my faculty and student collaborators on the “Does your phone make you feel safer?” project, funded by the 3 Cavaliers Project at the University of Virginia.

Image Credits:

- A multipurpose blue light phone, Fayetteville State University, 2018 (courtesy of Chuck Tryon) (author’s personal collection.)

- An appified aggregation of emergency media systems, 2022 (author’s screen grab.)

- Screenshot from interviewee Roxane, showing friends’ locations on her SnapChat (author’s personal collection.)

Dizon, Jude Paul Matias. 2021. “Protecting the University, Policing Race: A Case Study of Campus Policing.” Journal of Diversity in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000350.

Fisher, Bonnie S., Leah E. Daigle, and Francis T. Cullen. 2009. Unsafe in the Ivory Tower: The Sexual Victimization of College Women. SAGE Publications.

Glover-Rijkse, Ragan, Melissa Stone, Megan Alyssa Fletcher, and Gayas Eapen. 2020. “Mediating Precarity Through Mobile Apps.” AoIR Selected Papers of Internet Research, October. https://doi.org/10.5210/spir.v2020i0.11121.

Rentschler, Carrie. 2003. “Designing Fear: How Environmental Security Protects Property at the Expense of People.” In Foucault, Cultural Studies, and Governmentality, edited by Jack Z. Bratich, Jeremy Packer, and Cameron McCarthy, 243–72. Albany: State University of New York Press.