“I Am So Thankful for My Time at Peloton”: Self-Branding on LinkedIn

Emily McTiernan / University of Texas at Austin

On February 8, 2022, Peloton’s CEO stepped down and 2,800 of the company’s employees, including 20% of its total corporate workforce, were laid off. These organizational changes were made in response to the company’s decreased financial performance as Covid restrictions subsided and gyms opened after it experienced a surge in demand of its home fitness products during lockdowns earlier in the pandemic. However, in addition to reporting Peloton’s restructure, business press also addressed how the company’s laid-off employees used LinkedIn to post about their layoff status and begin their job search. This event also received attention from LinkedIn itself, as the platform aggregated these posts from laid-off Peloton employees on a LinkedIn News page.

Protocol described Peloton’s laid-off employees as doing “the standard laid-off-employee thing” by posting on LinkedIn about their experience. Additionally, the article described these LinkedIn posts as overwhelmingly positive, ultimately characterizing LinkedIn posts after being laid off as both a normalized practice and a self-branding effort. Therefore, this event serves as a useful object of analysis to study self-branding on LinkedIn. This brief article serves as an initial exploration of a growing trend among workers in traditionally less precarious positions to use self-branding online. By “less precarious” positions, I mean full-time workers for public corporations. These positions do not include traditionally precarious elements like low pay, lack of benefits, or temporary contracts. However, an increasingly unstable global economy has decreased job security in many industries, and mainstream, neoliberal discourse promotes individual actions like self-branding as the solution to these issues. In this case, laid-off Peloton workers looked to counter instability by branding themselves online in an effort to gain employment. These posts used self-branding strategies to present former workers in professionally advantageous ways that positioned them as ideal employees in a precarious labor market.

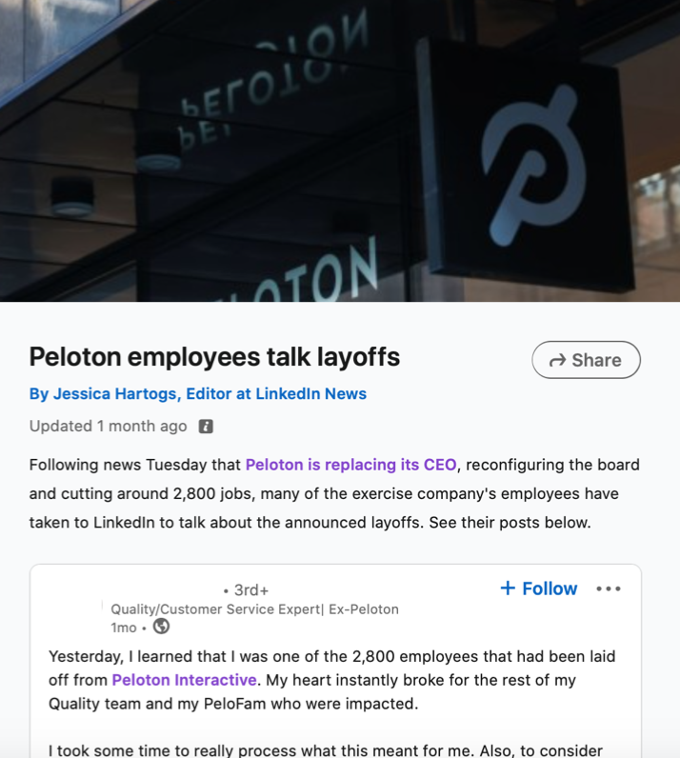

To find these posts, I used LinkedIn News, a way that LinkedIn aggregates professional news to its users. By aggregating these posts into a LinkedIn News page titled “Peloton employees talk layoffs,” LinkedIn deemed the posts from former Peloton employees relevant professional news for other LinkedIn users. Workers generally structured their posts into three parts: first, they told the news that they were part of the employees that were laid off, then spoke positively about their experience at Peloton, and ended by saying they were looking for new opportunities. Many posts began by clearly acknowledging the layoffs and often situating the worker’s status within the larger event. Most posts were either made the day of or day after the layoffs, and were expressed through statements like, “Today marks my last day at Peloton Interactive. After three years, I was laid off this morning along with thousands of other teammates and friends.” These opening statements showed how these posts balanced professionalism with authenticity, an often-used strategy in self-branding (Marwick, 2013, p. 196). These statements were often the only part of the posts that were negative in any way. Several posts described the layoff in emotional terms such as, “yesterday was a heartbreaking day” or “today has weighed heavy on my heart.” Including a brief discussion of the negative aspects of being laid off allowed the posts to serve as self-branding by enhancing the worker’s most lucrative aspects and underplaying those that don’t further their branding objectives (Khamis et. al, 2016, p. 199). Workers could be seen as “authentic” by expressing the negative emotions associated with being laid off while underplaying other negative emotions that could have been expressed like anger towards Peloton or worry about being unemployed. Describing the layoffs were the only time that these posts framed the event in any way negative, and the rest of the post was framed in positive, professional terms to brand and commodify this moment to find new employment.

In contrast to the negative emotions associated with being laid off, the majority of the post framed the worker’s experience at Peloton in positive terms. Focusing on lucrative, professionally advantageous aspects, this part of the post exemplified self-branding and served as a narrative of the worker’s experience that presented their idealized self (van Djick, 2013). Many workers described their time at the company using strongly complimentary terms like, “life changing,” “too good to be true,” or “dream job.” Workers also often talked about how much they accomplished during their time at Peloton. They framed their holistic Peloton experience as successful and positive by saying things like, “I felt I accomplished almost everything I wanted to over the past 4 years.” These statements were clearly framed to self-brand the worker in professionally lucrative ways. Another common theme was expressing thankfulness or gratefulness for their experience at the company through statements like, “I am so thankful for my time at Peloton. It’s been a dream come true!” The posts as a whole were largely positive because of their focus on the worker’s past experience with Peloton rather than the fact that they were currently unemployed. Workers positioned themselves as grateful to have had the chance to work for the company at all. In doing so, workers used self-branding to commodify their experiences and position themselves as ideal employees in an unstable labor market.

Most workers ended their posts by saying they were looking for a new role, and specifically asking their LinkedIn network to help with potential new employment. In doing so, workers explicitly expressed that their purpose of posting on LinkedIn was to obtain a new position. Through these statements, workers most obviously looked to turn self-branding into tangible, offline rewards (van Djick, 2013, p. 202). In doing so, these statements use self-branding as a way to gain personal control in an unstable job market that has shifted job security onto the individual (Khamis et al., 2013). This requires workers to use these posts to personally find their own employment. In doing so, these posts framed potential employment opportunities in idealistic terms, often using phrases like “next chapter,” “next adventure,” or “next challenge.” Workers framed being laid off as an opportunity and often said their next job was something that they were “excited about” and “looking forward to.” Again, the tone was positive overall because the focus was not on being laid off but the positive opportunity this situation provided. For example, one post stated, “I’m open and excited for new career opportunities. Please feel free to reach out if I may be a fit.” Workers also often stated their potential next role in positive terms asking their connections for companies that would be “a great fit” or the “next right opportunity,” where they could “make an impact” and “be a part of something great.”

An underexamined social media platform, LinkedIn has the potential to tell us a lot about how workers navigate changes in the labor market, including increasing worker precarity. This piece has addressed precarity in corporate workers and self-branding on LinkedIn, but perhaps most usefully serves as an exploratory study of LinkedIn’s role in an increasingly precarious labor market. Hopefully this initial exploration serves as a call for other scholars to uptake this important area of study as the labor market continues to rapidly change.

Image Credits:

- While Peloton faced financial troubles, its laid-off employees went to LinkedIn to secure new employment.

- Peloton’s and LinkedIn’s background photos on the platform. (Author’s screen grabs)

- LinkedIn News page aggregating Peloton employee layoff posts.

Khamis, S., Ang, L., & Welling, R. (2017, Aug 25). Self-branding, ‘micro-celebrity’ and the rise of social media influencers, Celebrity Studies, 8:2, 191-208, https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2016.1218292

Marwick, A. E. (2013). Status update: Celebrity, publicity, and branding in the social media age. Yale University Press.

van Dijck, J. (2013, Mar 14). ‘You have one identity’: Performing the self on Facebook and LinkedIn. Media, Culture & Society, 35(2), 199–215. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443712468605