By Any Platforms Necessary: The Makeshift Infrastructures of Bogota’s Public School Communities During the Covid-19 Pandemic

Andres Lombana-Bermudez / Universidad Javeriana

The crisis generated by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 continues to impact societies around the world. From culture to the economy, the public health emergency has transformed our lives and communities. One of the sectors more deeply affected by the pandemic has been public education. School closures forced teachers, students, and families to rapidly transition to diverse forms of distance learning and teaching, adapting their schedules, homes, and devices to the new dynamics of distance education.

According to the World Bank, still in 2021, more than 700 million students around the world continued to participate in some form of remote learning as schools remain closed in many countries. In Colombia, one of the most unequal countries from the Latin American region, national school closures affected more than 12 million children and youth enrolled in primary, secondary, and tertiary education. Today, the national education system completes almost 15 months of closure and its future remains uncertain as the country confronts the third peak of COVID-19. The shock of the pandemic has aggravated pre-existing education inequalities and impacted the lives of students in unprecedented ways, particularly those living in rural areas and urban poverty neighborhoods. As the Colombian Minister of Education recently announced, 243,801 students dropped out from the school system during 2020. In Bogota, the capital of the country, 34.934 students (2.5 %) abandoned their education in 2020, the majority of them (77.8 %) children and youth from low-income families (García & Maldonado, 2021).

Although the country and city governments confronted the emergency by developing several initiatives and platforms that aimed to support distance education, their top-down efforts did not work as expected, particularly in vulnerable contexts. Instead, continuing with the education of children and youth required the active participation and resilience of local education communities who deployed a grassroots and contextualized approach. These communities redefined their member’s roles and interactions, and, using any platforms and media they had in their pockets, experimented with different forms of distance teaching and learning. In this article, I reflect on how the pandemic crisis accelerated Information and Communication Technology (ICT) appropriation in Colombia, and discuss the tactics that teachers from Bogotanian public schools developed to support distance education in their communities.

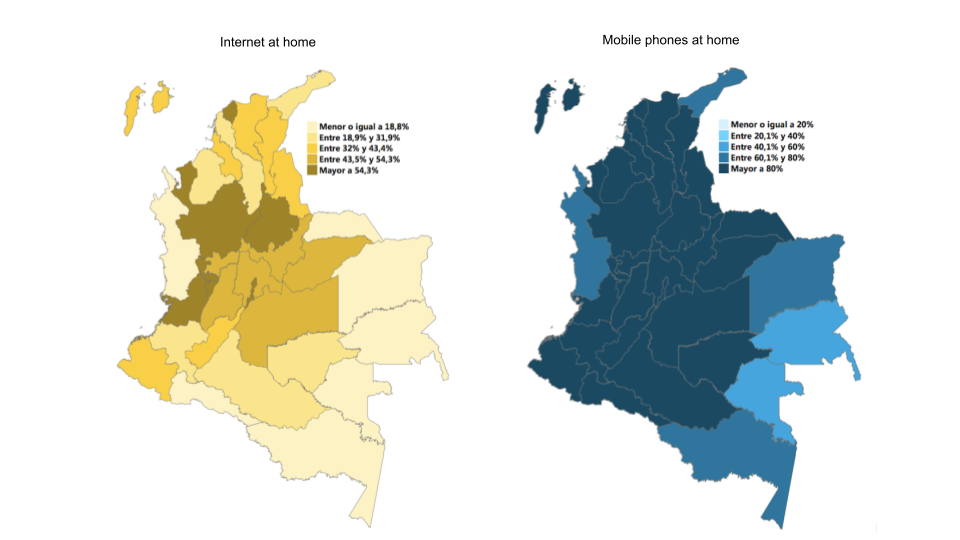

Accelerating Digital Transformation in Contexts of High Inequality

During the last decade, the Colombian national government has made several efforts to support the development of ICT infrastructure and promote its use among the population. The last three government terms have prioritized digital transformation in their development plans and designed public policies to close the Internet access gap, support ICT appropriation in the economic sector and public administration, bring computers to schools, and develop content for social impact (including educational resources). Despite the efforts, multiple digital divides (e.g. access, knowledge, participation, skills) persist in Colombia. By 2019, only 21.7 million people had Internet connectivity (43.4% of the population) and with a slow speed of 5.5 Mbps, way below the global average of 10.19 Mbps (MinTIC, 2020). The majority of connections are made through mobile phones, which are the most popular devices among Colombians. From 12.8 million 4G mobile lines in 2018, the country transitioned to have 30.9 million in 2019. However, the structural inequalities of income, education quality, and access to basic services (e.g. health, water, electricity) that have existed for a long time in Colombia, continue to shape the contours of the digital divides. For instance, the majority of people without access to ICTs live in rural areas and urban zones of extreme poverty (MinTIC, 2019).

According to the International Telecommunication Union ICT Development Index ranking, Colombia ranked 84 among 176 countries in 2017, with a value of 5.36 (scale 1 to 10), below five other Latin American nations (ITU, 2017). This index measures ICT readiness (infrastructure and access), intensity (uses of ICT in society), and impact (results/outcomes of more efficient and effective ICT use) using 11 indicators. Similarly, the National Center of Consultancy (NCC) in Colombia estimated an index of digital appropriation (scale 0 to 1) of 0,20 in 2016, 0,22 in 2018, and 0,23 at the beginning of 2020. The NCC measures the index combining 46 indicators of usage and 13 of intentions and has found that the majority of Colombian people use ICT at a basic level, mainly for entertainment and social communication. The country, therefore, was not well prepared for transitioning to online education during the COVID-19 emergency. As a 2020 brief published by the Inter-American Development Bank shows, the educational system of Colombia was developed only in two aspects: the existence of a central digital content warehouse (Aprender Digital) and the development of digital resource packages, while remained incipient in the availability of connectivity in schools and virtual tutoring (Rieble-Aubourg & Viteri).

However, the disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the process of digital transformation in Colombia. According to the last NCC study, the country advanced 20 years in terms of ICT appropriation in 10 months. The digital appropriation index went from 0.23 in February to 0.39 in November 2020. The increase was caused mainly by the diversification of the uses of technology by people who already had access, and not by an increment in the number of new users and Internet connections. Hence, although more people had middle (from 27% to 36%) and advanced levels (from 6% to 19%) of ICT use, the majority of them were located in urban areas and belonged to families with middle and high socioeconomic status (CNC 2021). This fact reveals the paradoxical nature of accelerating digital transformation in highly unequal contexts. Although it can have a positive effect on the people and communities who already have Internet access and are using ICTs at a basic and middle level, it can leave behind the ones who remain disconnected and lack access to technology, deepening existing divides.

Makeshift Infrastructures: Assembling of Digital Platforms and Analog Media

The challenge of continuing education during the COVID-19 crisis was hard for everybody. Every education community around Colombia, rich and poor, rural and urban, struggled to adapt to the new modalities of distance education. While some were more prepared in terms of ICT infrastructure, uses, and skills, others had to quickly improvise with the resources and knowledge they had at hand. Given the multiple inequalities that impact public schools in Colombia, their adaptation to remote teaching and learning required a particular kind of approach in which teachers, parents, and students leveraged any platforms and media necessary to continue their educational process. The heterogeneity of tactics that public school educational communities developed shows their capacity to configure “makeshift infrastructures” (Afanador-Llach & Lombana-Bermudez) in contexts characterized by precarious internet connectivity, lack of access to computers, and basic uses of ICT. This kind of infrastructure can be understood as improvisational assemblages of platforms, tools, services, and practices that ordinary people creatively orchestrate to adapt the conditions of the dominant order to their own ends.

In a city of 7.7 million people, the Bogota public school system is composed of 400 institutions that provide primary and secondary education to children and youth (789,157 students were enrolled in March 2020). Many of these public schools serve low-income families that confront poverty, unemployment, and deficient housing among other challenges. According to recent official data, 1.1 million people live in poverty in Bogota. It is precisely among the education communities located in the most vulnerable neighborhoods around the city where we can find examples of the diverse tactics that allowed (and continue to allow) teachers, parents, and students to engage in distant learning and teaching. Their tactics combined the use of mobile phones, digital platforms—including social media, messenger apps, learning management systems (proprietary and open-source), governmental and independent content hubs—and analog media such as printed guides.

Last year, as part of the Hablatam project, I had the opportunity to interview teachers from low-income public schools located in the south of the city. They told us that the government emergency plan of online classes, learning platforms, and content hubs did not work for their communities given their barriers of connectivity and access to computers. Instead, they had to rapidly create their own contextualized plan in collaboration with school administrators, parents, and students taking into account their particular conditions of ICT access, their skills, and media practices. They built hybrid and temporary infrastructures that relied on mobile phones as the main device for connecting all the actors of the community and supporting remote teaching and learning. Moreover, their infrastructure also included the printing of paper guides that were picked up by parents at the schools every month. Mobile phones (shared among family members) allowed students and parents to interact with teachers, submit their assignments, receive feedback, and access content online. Although the main platform used for the interactions was the proprietary messaging application WhatsApp—which allowed the easy exchange of texts, PDF files, photographs, audios, and videos at low data rates—students also interacted with content that teachers created and uploaded to YouTube, Facebook, personal blogs, and Google Classroom. For instance, one of the teachers from the Bosa public school created a personal blog for his robotics class with tutorials for online activities. Another teacher from a school in Usme leveraged his music production knowledge as a hip-hop MC to create an audio podcast series for a social science class. He interacts on WhatsApp with his students sharing the podcast files and collecting audio assignments that the students complete recording their voices.

Education Innovation from the Margins

The tactics developed by Bogota public school teachers during the COVID-19 emergency illustrate how vulnerable communities have been able to build and use “makeshift infrastructures” leveraging the platforms, media, and skills they have at hand. I have mentioned just a couple of examples, but many others need to be documented, analyzed, and shared. Although the pandemic has amplified inequalities in all societies around the world, it has also opened opportunities for innovation from the margins. Particularly in education, the early evidence from Bogota public school communities reveals the emergence of new modalities of remote and distance learning that are diverse, and innovative despite their limited access to Internet connectivity and computers. The formats, pedagogies, and interactions that have been developed during the crisis in vulnerable contexts have the potential of transforming the future of public education, schools, and communities.

Image Credits:

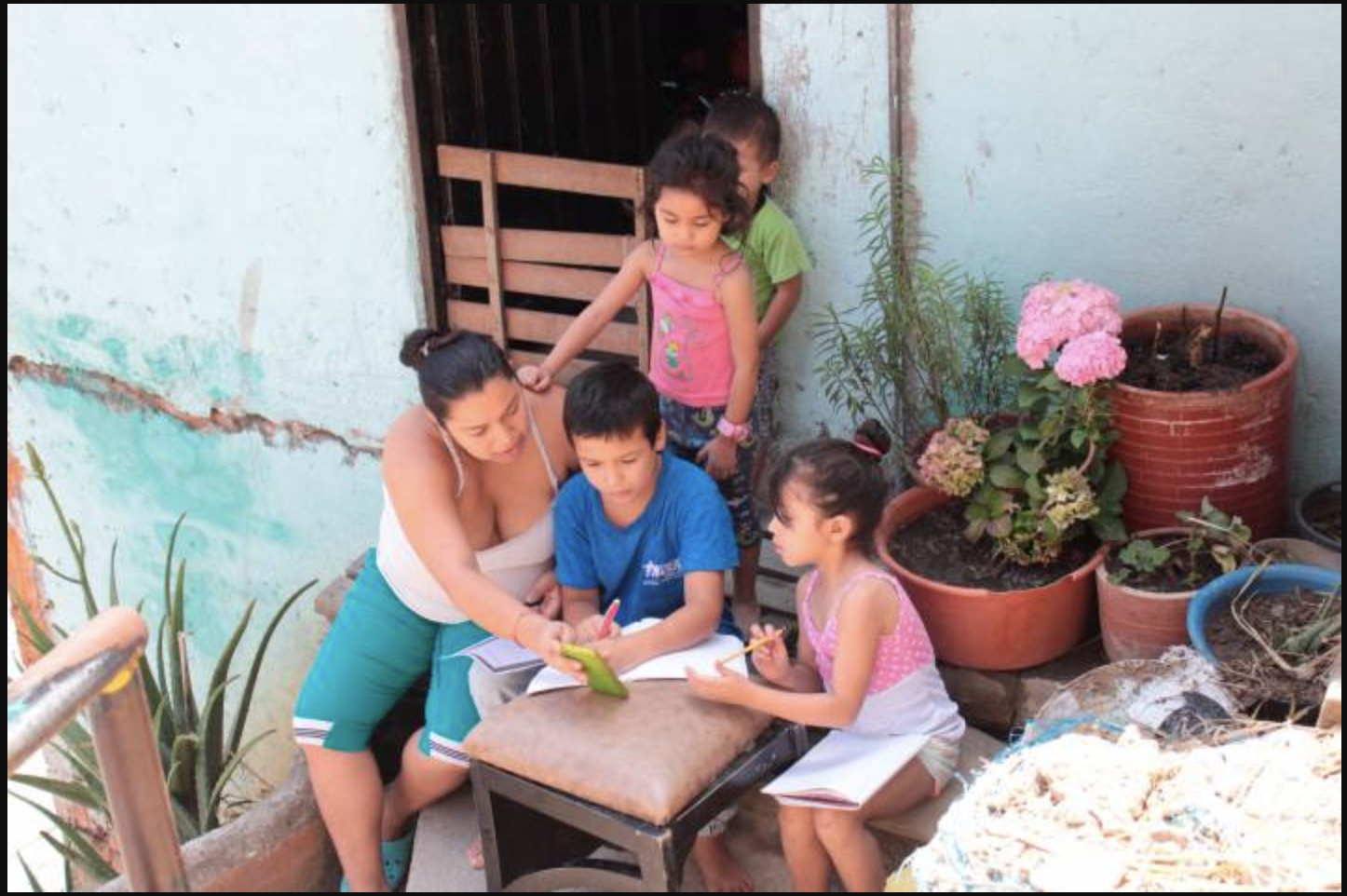

- Children using a mobile phone, with the assistance of an adult, to continue with their education during the pandemic in Colombia. From La Vanguardia.

- Maps of ICT access in Colombia. Right: proportion of homes that have Internet at home. Left: Proportion of homes that have at least one mobile phone home. From Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística (DANE) Boletín Técnico: Indicadores básicos de tenencia y uso de tecnologías de la información y comunicación.

- Basic digital conditions of Latin American Educational Systems. Measures by the IDB’s Educational Management and Information Systems (EMIS) study using data collected by the IDB’s Education Division. From Inter-American Development Bank.

- WhatsApp has become one of the the main platforms for educational communities living in contexts of precarious ICT access. From Somos Periodismo.

- A Bogotanian public school teacher created a podcast he distributes on WhatsApp to continue teaching his social science class. YouTube video.

Afanador-Llach, M. & Lombana-Bermudez, A. (forthcoming 2022) “Developing New Literacy Skills and Digital Scholarship Infrastructures in the Global South: A Case Study.” Global Debates in the Digital Humanities. University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis.

CNC – Centro Nacional de Consultoría (2021) El Salto Digital. Study presentation. Bogota, Colombia.

García, S. & Maldonado, D. (2021) COVID-19 y Educación En Bogotá: Implicaciones Del Cierre De Colegios Y Perspectivas Para El 2021. Alianza ProBogotá – Escuela de Gobierno, Universidad de los Andes.

ITU (2017) Measuring the Information Society Report 2017: Volume 1 and 2, ITU, Geneva.

MinTIC (2020) Boletín Trimestral de las TIC. Bogotá, Colombia, abril de 2020. Minister of ICT website. Bogotá, Colombia.

MinTIC (2019) La mitad de Colombia no tiene internet. Minister of ICT website. Bogotá, Colombia.

Rieble-Aubourg, S. & Viteri A. (2020) COVID-19: Are We Prepared for Online Learning? CIMA Brief #20. Centro de Información para la mejora de los Aprendizajes. Inter-American Development Bank.

This article and the statistics collected here I think will be very useful!

It was interesting for me to read everything and go even deeper into this topic.

I think everything related to covid will be studied for a long time to come. This is the first time we have encountered this and mistakes just need to be found and worked through!

For this reason, we would like to offer you a much better alternative. Take a break from studying. You have deserved it. You can focus on something else now. Do what you enjoy. In the meantime, one of our highly qualified writers will be working on the task of writing a discussion paper especially for you.