The Visceral in Latinx Horror

Orquidea Morales / State University of New York, Old Westbury

One of the pleasures of watching horror movies is the visceral response, that adrenaline you get from being terrified from the safety of your couch of course. Bodily responses, I would argue, are necessary to define a film or a moment in a film as horrific. In this column, I demonstrate how the genre of Latinx horror can include horror and non-horror films based on the positionality of the audience and their visceral response. By this I mean that by taking into account the visceral response we have to images of violence and the death of brown bodies on screen, we can broaden our definition of Latinx horror. By doing so, movies coming from different genres and different distribution modes can be read together to help us better understand representation of Latinxs and Latinx issues such as immigration and the border. Thereby we can name the real monsters that shape and unfortunately destroy the real lives of Latinx and Latin American communities.

If horror is the evocation of a physical response along with a sense of fear and dread and this is often accomplished, as Linda Williams and other scholars argue, through identification with what we see on screen, then where does that leave us – the Latinx fans that love the genre, yet are rarely seen on screen, let alone as leads?[1] How do Latinxs watch horror movies and what do horror and non-horror movies tell us about the Latinx experience?

There are multiple ways to approach these questions that can help us rethink how we define generic categories, as well as the role Latinx audiences and creators have in horror. Here, I’ll provide a brief introduction to three approaches, as well as examples of immigration in film that help illustrate them.

Eviscerate the Gaze:

First, we can think about the long legacy of scholars that have written about how women and people of color use the gaze and learn to read against the grain. For example, bell hooks argues that there is a constant negotiation between spectator and text, where the spectator is not a passive receiver positioning themselves in the body of the “hero,” but rather they bring in their own histories and understandings of film into the conversation. The gaze, for hooks, is a site of resistance for colonized communities to color.[2]

I’ll give a personal story to explain this approach. I was born in Mexico and naturalized at age 6, so I had the privilege of crossing the border legally. Yet whenever the border patrol asked me where I was born, I would automatically say Mission, Texas. I was never taught to do this, I just instinctively knew that it was easier and there would be less questions if I lied. Even though we crossed the border back and forth at least once a week, there was and still is a visceral response to the border patrol vehicles, the border wall, and the checkpoints. Even images of these horror architectures and machines make my body react, including in non-horror films. Case in point is the movie Coco (2017), particularly the scene where Hector tries to cross the border only to be chased by the undead border patrol. When he tries to cross the marigold bridge, the petals turned into liquid dragging him down and facilitating his capture and deportation.[3] This scene was intended to be a funny and playful way to let us learn more about Hector’s character and desire to return to the world of the living. Latinx horror is about reading against the grain and feeling beyond what the text dictates by bringing in our own experiences. In doing so, that scene can be read and experienced as horrific, a reminder of the real-world policies and enforcements that cause real deaths on the border.

Eviscerate the Genre:

If Latinx characters are few and far between in traditional horror films, where can we go to for horror? Much like Williams does by placing horror, melodrama, and porn under the body genre label, I argue that to truly trace the evolution of Latinx horror films we have to look at films not traditionally considered horror and think about how these films contributed to the themes and imagery of Latinx horror.

One example is El Norte (1983) directed by Gregory Nava. It follows two siblings, Enrique and Rosa, as they travel from Guatemala to the U.S. in order to escape the ruthless violence and corruption in their hometown. Early in the film, Enrique leaves his home in search of his father, a farmworker and revolutionary in Guatemala. Enrique finds his father’s decapitated head hanging from a tree. Enrique tries to climb the tree but is quickly captured by a soldier who tries to arrest him. However, Enrique breaks free and with a machete hacks the soldier to death. The jump scenes between the machete and Enrique’s face along with the sharp music are reminiscent of many slasher films. Enrique, however, is no masked boogey man nor is this the start of a killing spree. He is a young man who has just lost his father to a gruesome death and now fears for his life.

Further, a key scene in the latter half of the film takes place in the sewers under the Mexico-U.S. border. Enrique and Rosa cannot find a way to cross the border through the checkpoints or the desert and are forced to travel through the dark and rat-infested sewers. The scene slowly and painfully draws the viewer through the sewers with the siblings. We too close our eyes in horror as Enrique begs Rosa to close her eyes and grab on to him since he does not want her to see the rats and chaos all around.

In a recent interview, Gregory Nava described the tunnel scene as “terrifying, as anything in a Hitchcock movie, or any horror movie that you’d ever seen.”[4] I argue that Nava uses horror techniques including music and lighting in these two scenes to have us identify with Rosa and Enrique. As audience members, our visceral response to the pain of their forced migration compels us to grapple with the reality of military coups, the destabilization of governments around the world by the U.S., the man-made border, and even racism and xenophobia within Latinxs.

Eviscerate the Border:

This brings us to a final approach we can take, distribution. Recently there have been a number of articles and blog posts praising the growth of political horror, horror with a purpose. However, horror films have a rich history of sociopolitical commentary, hidden behind viscera and excess of course. The idea that horror is now more polished and more relevant reflects the early dismissal of the genre as cheap and vapid entertainment. To get a fuller picture of Latinx horror we need to include movies distributed in ways that have traditionally been dismissed in academic conversations about Latinx film, like direct to video and direct to streaming.

Thankfully, the realization that these modes of distribution are a wealth of objects of study is growing. One case is the film Culture Shock directed by Gigi Saul Guerrero and released via Hulu through their Into the Dark Series. The July 4th premiere of the movie was no coincidence since the movie takes place during that celebration. The story follows a pregnant young woman, Marisol, as she attempts to cross the border into the U.S. accompanied by a coyote and fellow travelers, including criminal Santo Cristobal and young Guatemalan Ricky. As they attempt to cross, they are stopped first by the cartels, then by the border patrol. Marisol wakes up in a perfect little house wearing a pastel yellow dress and having already given birth. Of course, not everything is as it seems when Marisol slowly beings to realize that this seemingly perfect town is a detention center for immigrants. Think Stepford Wives (1975) but with immigrants.

Culture Shock has rightfully received great critical and fan reception. It parodies the immigration system in the U.S. and presents a glimpse into a dystopic future of immigration control. Other films, including shorts that have been distributed via streaming and direct to video or tv, such as El Chupacabra vs. The Alamo (2013), From Dusk till Dawn 3: The Hangman’s Daughter (1999), and Ay Mis Hijos: Encounters of la Llorona (2013) all dealt with the U.S.-Mexico border in one way or another. This is a small sampling of what is available outside of mainstream and theater distribution. To better understand Latinx horror as a genre and the complexity in which movies deal with difficult issues, we need to expand our approach to other modes of production and distribution.

Latinx Horror as Process:The three films discussed here are separated by time, genres, and distribution among other things. However, in this brief analysis, I have shown how they all deal with issues of migration and the border through horror. Again, if Latinxs are fans of horror and yet historically excluded from roles in front of the screen, we have to find other ways to constitute this genre and to find our place and voice not only as fans but as creators of it. By reading these three films together, for example, we can see how Latinx horror films serve as battlegrounds for important Latinx issues such as immigration and the border. We still need stronger representation in front and behind the screen in Hollywood horror films. While we fight for that to happen, however, I suggest we mine the rich terrain of Latinx horror that already exists and begin mapping and cementing it as an important object of study.

Image Credits:

- Still from Culture Shock (2019) directed by Gigi Saul Guerrero. (author’s screengrab)

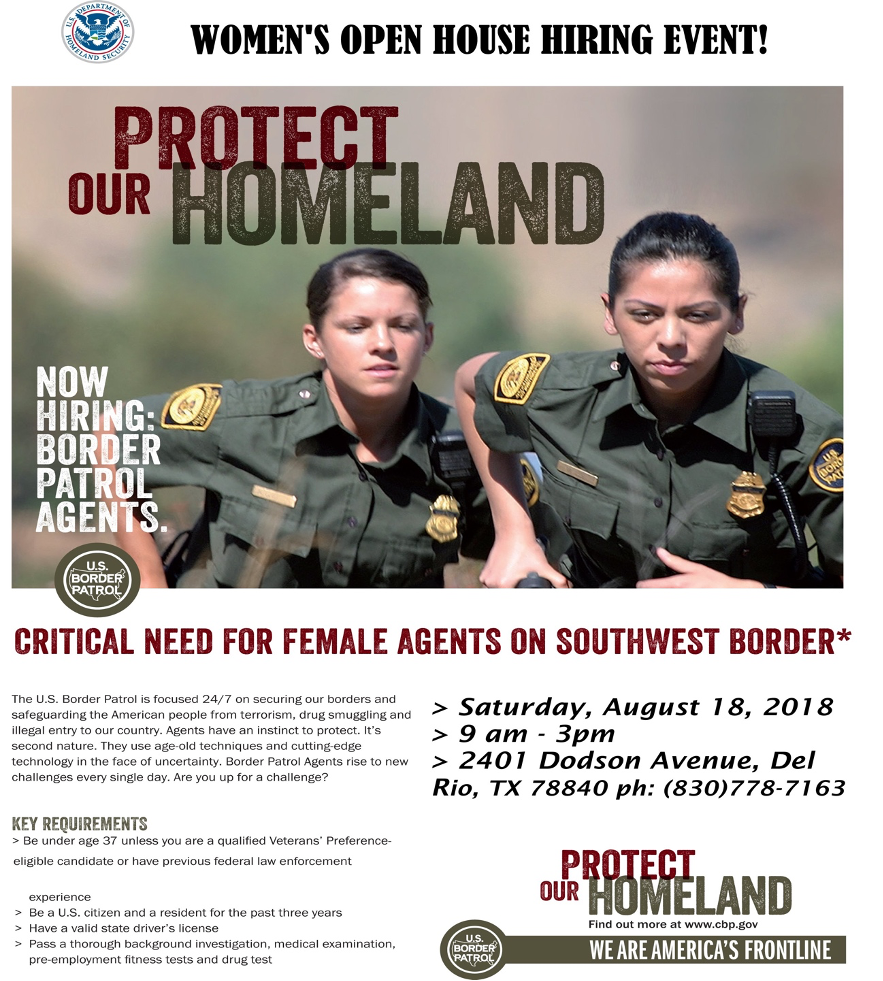

- Flyer distributed by U.S. Customs Border and Protection Agency to recruit more women in south Texas. Shared by @CBPSouthTexas on July 10th, 2018.

- In Coco (2017), Hector is shown drowning in the marigold bridge after attempting to cross the border without documentation. (author’s screengrab)

- Still of Enrique and Rosa in the sewers crossing from Tijuana to San Diego from the film El Norte (1983). (author’s screengrab)

- Marisol and Santo Cristobal after breaking out of the detention center in Culture Shock (2019). (author’s screengrab)

- Stills from the short film Ay Mis Hijos: Encounters of la Llorona (2103) directed by Fabian Arroyo. (author’s screengrab).

- Williams, Linda. 1991. “Film Bodies: Gender, Genre, and Excess.” Film Quarterly, 44(4), 2-13. [↩]

- hooks, bell. 1992. Black Looks: Race and Representation. Boston: South End Press. [↩]

- In my article “Horror and Death: Rethinking Coco’s Border Policy,” I further explore the horror aspects in the film. [↩]

- Aguirre, Jessica Camille. 2019. “‘The Border Is Its Own World’: Immigration Milestone El Norte, Revisited.” Vanity Fair, Sept. 12. [↩]