Remediating Liveness

Alyx Vesey / University of Alabama

Just imagine…. you’re standing in a big warm crowd, two songs into hearing this Waxahatchee album live, your friend wiggles back through next to you and hands you a beer, you say “thanks dog I got the next one,” you take simultaneous sips and go on vibing :’)

— Jia Tolentino (@jiatolentino) April 14, 2020

This is the second installment of a three-part series entitled “Making Music in a Crisis.” The first installment in the series can be found here.

On March 7, 2020, South by Southwest became one of the first major U.S. events to get cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Though SXSW struggles to maintain its indie roots as big tech and gentrification transform Austin, the multimedia conference and festival helps kick off tour season, which stretches from mid-March through Labor Day weekend. Soon after, my inbox swelled with postponement notices as artists were left with no place to play.

Initially, festival organizers presented SXSW’s cancellation like a hiccup that would work itself out if we held our breath. Coachella and Stagecoach were first rescheduled for October before they were eventually cancelled. But as the pandemic raged through spring 2020 and the Trump administration abdicated responsibility to state government, the virus’s impact on the live music industry grew.

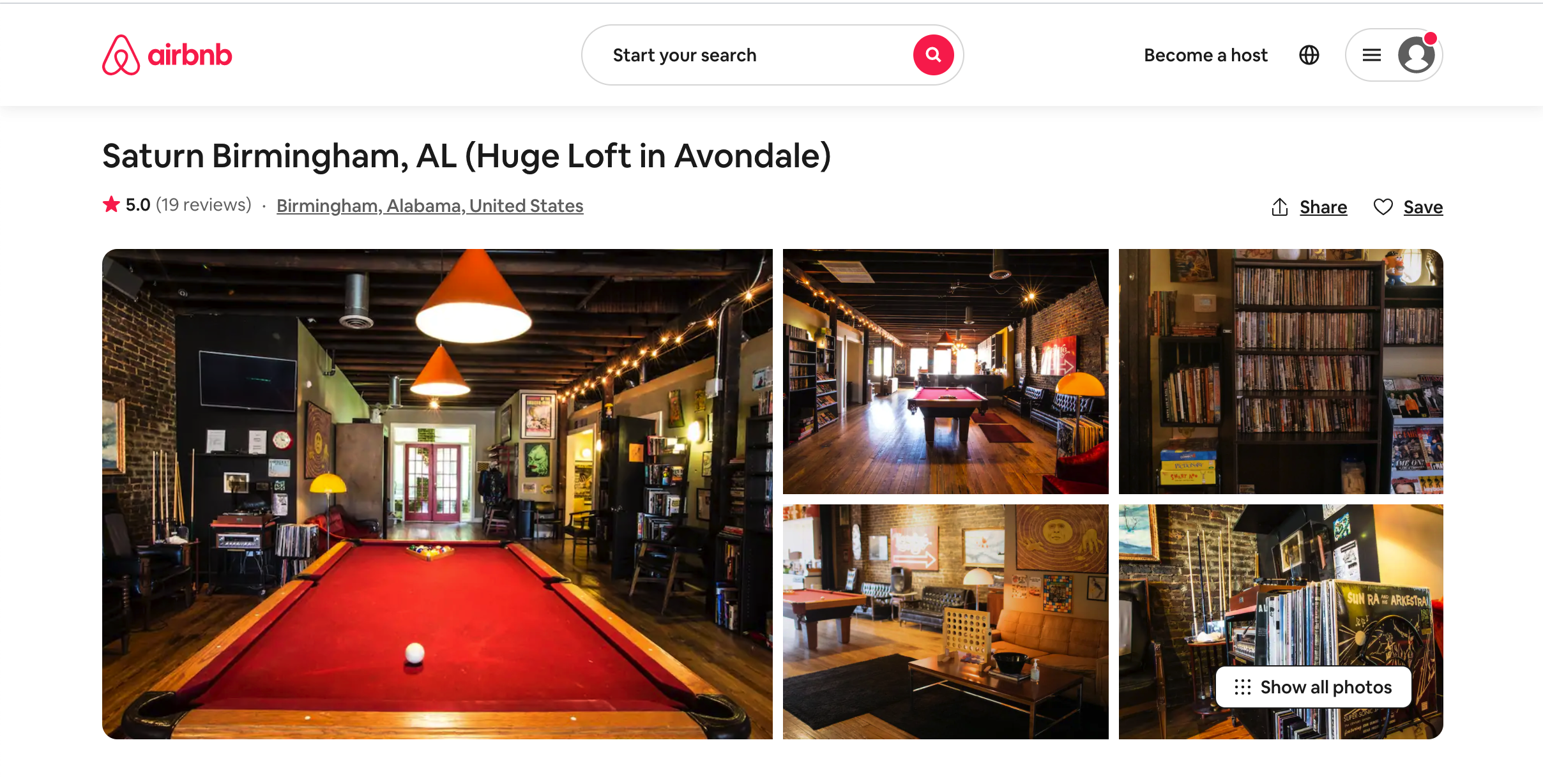

In 2019, PricewaterhouseCoopers projected that ticket sales and tour sponsorships would generate $29 billion in global revenue. The touring industry supports an entire ecosystem of live music professionals, including road crew, promoters, and venue staff. Furthermore, live music contributes to a scene’s economy. For example, SXSW 2019 brought in $356 million, including $200 million that was funneled into Austin’s clubs, bars, and restaurants. Thus, it was alarming when Pollstar estimated that the pandemic cost $9 billion in cancellations a month after SXSW’s cancellation. After the Memorial Day Weekend spike, Americans for the Arts reported that 62 percent of U.S.-based artists were unemployed. By August, independent music venues around the country had to decide whether to close, have a corporate promoter incur their debt, or support legislation like Save Our Stages, a grant program that distributed $15 billion in federal aid to venues as part of the CARES Act in December. Venues like Saturn Birmingham also offset closure costs by renting out its musicians’ loft to Airbnb.

Musicians already had to scramble to make a living before the pandemic. Artists earn roughly a tenth of a penny per stream on streaming platforms like Spotify, which pay out around 70 percent to rightsholders by dividing individual streams by a service’s total streaming number. As a result, most contemporary musicians make their living on the road and supplement their income with licensing agreements, endorsements, merchandise, and various odd jobs.

Furthermore, musicians are also responsible for cultivating their own followings on social media. Tim Anderson, Jeremy Morris, and Nancy Baym argue that such conditions necessitate musicians to involve their fans in their work through crowdfunding and recruiting them to make production and packaging decisions for their projects while shouldering the administrative and emotional burden of managing networked communication (2014; 2014; 2018). Baym describes these professional expectations as “relational labor,” or musicians’ “ongoing, interactive, affective, material, and cognitive work of communicating with people over time to create structures that can support continued work” (19). In a year when concerts could not happen in person, musicians’ online performances serve as instructive forms of relational labor.

In the pandemic’s first few months, most musicians remediated venue space by figuring out which part of their home was most conducive to staging performances on Zoom. One illuminating site for such negotiations is Tiny Desk Concert. Originally launched in 2008, Tiny Desk has the makeshift charm of a house party that invites fans and musicians to squeeze together and peruse the host’s well-appointed bookshelves. On March 24, 2020, Soccer Mommy became the first musician to record a Tiny Desk (Home) Concert from her Nashville home to make up for her cancelled SXSW appearances and her postponed tour for her new album.

As the pandemic burned through 2021, Tiny Desk (Home) Concert domesticated the concert while giving viewers intimate glimpses of musicians’ relational labor. Guests perform in living rooms, on porches, in backyards, bedside, in cars, and across time zones. Production values vary widely and illustrate artists’ divergent circumstances and priorities. Between-song banter also helps musicians contextualize their music by meditating on and advocating for sociopolitical change during a summer shaped by civic resistance against white supremacist police brutality, a fall defined by one of the most consequential presidential elections in U.S. history, and a winter pockmarked by another outbreak and the Capitol insurrection.

Tarriona “Tank” Ball of New Orleans soul group Tank and the Bangas demonstrated artists’ ability to turn limited resources and existential dread into art. She delivered a lively solo set at the end of March 2020 while freestyling over beats she made with a coat hanger, a pen, a suitcase, a cassette tape, a cocoa butter jar, and a Korg app she played with on her iPad. Ball’s resourcefulness was born of necessity. New Orleans’ mayor LaToya Cantrell had just issued a stay-home mandate that disallowed her band from gathering. But her performance also reveals how adaptive and inventive musicians have to be. It was amid this fit of unplugged chaos that Ball created “Don’t Go Out to the Cookout,” a quarantine anthem that shaped safety protocols into a memorable pop song and expressed the necessity of precaution from a Black woman’s perspective as it was revealed that the coronavirus was disproportionately impacting Black communities.

While NPR’s Tiny Desk series showcased a range of production aesthetics, other concert series sought to emulate the Before Times live experience. Furthermore, while Tiny Desk prioritizes inclusive eclecticism in its booking decisions, such strategies disallow NPR to showcase one specific genre or style. Thus, a productive counterpoint to Tiny Desk is Verzuz, a battle series that producers Tim “Timbaland” Mosley and Kasseem “Swizz Beatz” Dean launched on Instagram Live in late March to center R&B and hip-hop acts.

Verzuz drew headlines with new jack pioneers Teddy Riley and Babyface’s face-off and rematch and neo-soul icons Jill Scott and Erykah Badu, which garnered over 500,000 viewers. But while the first wave of guests filmed themselves from their laptops, eventually the battles were filmed on stage at local venues. Verzuz also brought in Apple Music and Cîroc as sponsors to help cover production and promotional costs. Brandy and Monica’s late August match-up attracted over a million viewers and featured a voting PSA from Vice Presidential candidate Kamala Harris.

Verzuz followed this event with Patti LaBelle and Gladys Knight’s auntie master class. Recorded at the Fillmore Philadelphia near LaBelle’s home, the face-off showcased the singers’ easy rapport and unflagging professionalism and even made room for burgeoning Twitter sensation Dionne Warwick to end their battle in a draw by leading them through a rendition of “That’s What Friends Are For,” a nod to the trio’s 1986 HBO concert film, Sisters in the Name of Love.

While LaBelle and Knight’s Verzuz was a display of diva solidarity, its promotional campaign for Instagram ginned up a playful rivalry that favored LaBelle’s savvy navigation of digital-age relational labor as an influencer and lifestyle brand. Knight kicked off the campaign with a 30-second video of her singing “Midnight Train to Georgia” to herself while making a banana pudding. LaBelle upstaged Knight by preparing a multi-course meal that included a sweet potato pie from her Good Life food line while singing her 1986 ballad, “Finally We’re Back Together.” Verzuz also recruited LaBelle superfan James Wright Chanel to make an explainer video for how to watch the show on Apple Music while wearing Gladys and Patti drag. While both women use Instagram, LaBelle is a more active presence with a larger following that she supplied with cooking videos and other quarantine content after cancelling her 2020 concert dates.

While Verzuz recently drew big crowds and generated millions of streams for Ashanti and Keysia Cole’s face-off and the D’Angelo showcase, the series still has to contend with the health risks built into live performance. Babyface delayed his original appearance because he tested positive for COVID-19, a grim reality for many working musicians. As a result, some artists have used virtual concerts to mitigate the physical demands of touring in a post-human future.

In August, the Weekend held TikTok’s first virtual concert. The Weeknd Experience drew over two million fans and helped promote the singer’s fourth album, After Hours, a nihilist synth pop suite released during the pandemic’s first stage. In some ways, the Weeknd is uniquely well-suited to the virtual format. The Weeknd has made a career out of ambivalence, bending his mournful falsetto above malevolent ballads about late-night hedonism. He externalized his turmoil on After Hours by using plastic surgery as a metaphor for celebrity self-promotion that echoes Michael Jackson’s monstrous transformations. He also likes to hide behind technology. He began his career by uploading songs with cryptic key art on YouTube and declining interview requests once critics seized on his narcotized sound. He also collaborated with Daft Punk, a French electronic duo who dressed like robots to avoid showing their faces in public.

But it is unclear if the Weeknd Experience is predictive for musicians’ relational labor as concert performers. Artists staged concerts on Fortnite and Minecraft before the TikTok event. The Weeknd leveraged the concert’s success by booking Pepsi’s Super Bowl Halftime Show. What may be more predictive is TikTok’s recent licensing agreement with Universal Music Group as the last member of the Big Three to partner with the video-sharing app. The deal gives TikTok users access to UMG’s catalogue, which includes the Weeknd’s discography through Republic Records. This may serve as another revenue stream for artists, though I fear TikTok and UMG will unevenly benefit from this arrangement. For now, I’ll hold out hope that I get to see Bikini Kill in November.

Image Credits:

- Tweet from @jiatolentino, April 14, 2020.

- The Airbnb listing for the Saturn Birmingham musicians’ loft. (author’s screengrab)

- Tarriona “Tank” Ball’s Tiny Desk (Home) Concert.

- The Patti LaBelle vs. Gladys Knight Verzuz battle.

- Patti LaBelle’s promotional video for her Verzuz event.

- The Weeknd’s performance of “Blinding Lights” from his TikTok concert.

Anderson, Tim J. Popular Music in a Digital Economy: Problems and Practices for an Emerging Service Industry. New York: Routledge, 2014.

Baym, Nancy. Playing to the Crowd: Musicians, Audiences, and the Intimate Work of Connection. New York: New York University Press, 2018.

Morris, Jeremy Wade. “Artists as Entrepreneurs, Fans as Workers.” Popular Music and Society 37, no. 3 (2014): 273-290.