Your Mascot Could Never: The Effectiveness of Benny the Bull on Tiktok

James Bingaman / University of Delaware

In an article identifying the biggest sports media trends, global marketing giant, Nielsen, listed “capturing the attention of Gen Z” (Nielsen Sports, n.d., para. 8) as one of the trends to watch out for in 2020. Gen Z — affectionately named “zoomers” — are those born after 1996 (Parker & Igielnik, 2020) and are often associated with having their heads buried into their phones or taking part in the latest dance trend. Currently, a lot of discourse surrounding Gen Z is related to their use of TikTok, which is currently the top downloaded app of 2020, and the 6th largest social media site (Sehl, 2020). With almost half of all users being below the age of 24 (Sehl, 2020), TikTok has almost become a necessity for creators, brands, and organizations to reach out to this younger generation. Sports organizations are no different. Effective communication via social media is integral to the success of sports organizations (Siguencia et al., 2016) so being able to successfully navigate this new social media environment should be one of the main goals for every sports organizations’ media strategy in 2020 and beyond. This short essay will focus on the innovative way that the Chicago Bulls have utilized TikTok by focusing less on sports and instead focusing on an often underappreciated source: their mascot, Benny the Bull.

Benny the Bull

Beginning in the late 1960s, Benny the Bull became the National Basketball Association’s (NBA) first mascot and has enjoyed unrivaled national and international popularity ever since (Borrelli, 2019). Already a success on other social media platforms, Benny the Bull has transcended the sports realm and has become somewhat of an influencer on TikTok, partaking in collaborations with some of the platform’s biggest stars (e.g. Charlie D’Amelio). Mascots having social media accounts is not a new phenomenon as teams will often use mascots online to increase emotional connectivity with fans (Wandel, 2018), especially through TikTok. Benny the Bull has already led other teams to use their mascots more frequently on TikTok (Moran, 2019). However, Benny stands out from the rest. By the end of August 2020, Benny had 2.9 million followers and 46.6 million likes, whereas the Chicago Bulls had just shy of 400 thousand followers and 1.6 million likes. There are several reasons why Benny has thrived on TikTok, however, this piece will look at three main reasons: the influence of dancing on TikTok, the difference in how the platform is used, and the formation of parasocial connections between Benny and users.

@bennythebull @charlidamelio @dixiedamelio @addisonre

♬ Bagaikan Langit(cover) – _ucil👑

LeBron James won’t “renegade”

According to Siobhan Burke (2020) of The New York Times, “TikTok has become a wildly popular global platform for dance, especially among teens, with tools that make it easy to film yourself dancing to music, integrate special effects and share the results” (para. 5). Although TikTok is a platform that welcomes creators from all backgrounds and styles, overwhelmingly, dance has taken over as the predominant art form. Knowing that these short little dance routines thrive, it’s easy to see why a mascot could be successful in this kind of environment. We are used to seeing mascots dance. We see it in stadiums, arenas, and on our televisions when we watch sporting events. Even the official Benny the Bull website (Benny the Bull, n.d.) lists “dancing” as Benny’s number one activity. Although the identity of Benny the Bull is kept under wraps, the most recent performer to don the red fur was Barry Anderson (who has since retired after 12 years as Benny), a former theater and dance student at the University of Montana known for his high-flying routines (Borrelli, 2019). The Chicago Bulls took this high-flying, dancing red bull virtual and found a new, niche home that catered towards that kind of act.

@bennythebull ‼️NEW DANCE‼️ Who do you want to see do it next? ##BullsBMOChallenge ##dance

♬ Benny Dance Challenge – chicagobulls

Despite his presence in a viral video from 2013 of the Miami Heat taking part in the Harlem Shake trend, along with some of the goofy antics with his family that he posts on Instagram, it’s hard to see LeBron James — or any major athlete for that matter — taking part in weekly dance trends on TikTok (like the video shown above). The renegade dance routine, created by Jalaiah Harmon, went viral on TikTok earlier this year and was even featured during NBA All-Star weekend (Madu, 2020). Sure, athletes could post a video of themselves doing the renegade on their personal accounts, but official sports accounts often use footage from games, interviews, or clips from extended pieces that are posted across all social media platforms, so taking the time to teach LeBron routines like the video above or to ask him to give up time to dance seems unlikely. Likewise, front office members that might have the time to dedicate to dancing on TikTok won’t grab the same attention of an audience as a professional athlete would. On a platform where dancing thrives, the only logical answer is to use the mascot, not only because they have a history of dancing, but because this is a more casual way to engage with fans rather than getting a professional athlete involved.

TikTok is not like any other platform

TikTok is not like other social media platforms. Other social media platforms like Twitter are used to build relationships and share information with others via text (Wang & Zhou, 2015). In what could be seen as a competitor, Instagram relies on users sharing pictures (Waterloo et al., 2018) that fall within eight categories — friends, food, gadgets, captioned photos, pets, activities, selfies, and fashion (Hu et al., 2014). While users can also post videos on Instagram, TikTok is different in that it’s entirely predicated on being a video platform. Unlike photos, video can increase immersion and interaction, ultimately extending the experience for users (Dinhopl & Gretzel, 2014). Mobile videos that are shot in the first-person are more engaging as they increase immersion, social presence, and entertainment for users (Wang, 2020). Fans engaging with Benny the Bull on TikTok are not just doing so through photos (Instagram) or text (Twitter) but are instead absorbed into a world where, for just a moment, mascots are not people in costumes but are performers and characters they can connect with.

Individual vs. Team

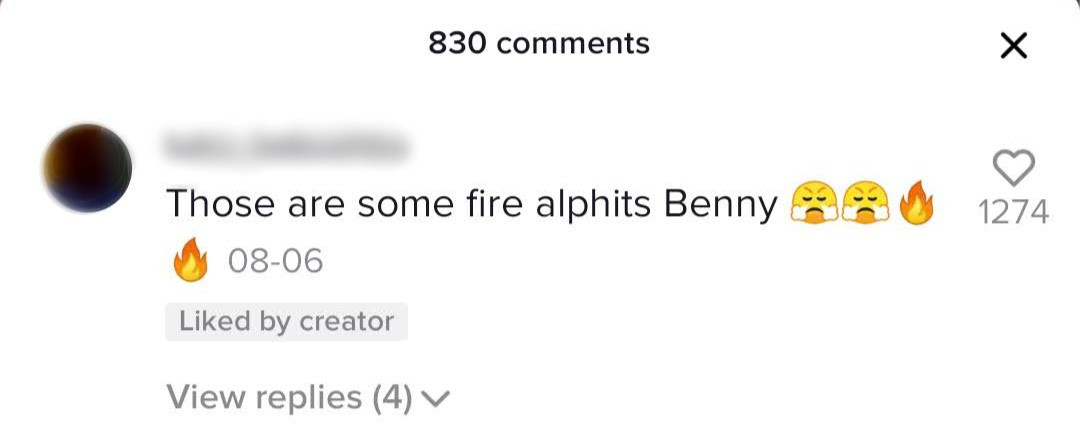

Parasocial interaction refers to the perceived one-way relationship that exists between a viewer and a media figure that can be analogous to real relationships (Weiss, 1996). Social media has afforded users with new avenues to connect and engage with their favorite media figures (Pegoraro, 2017) including athletes or other sports figures (Kim & Song, 2016). There is no reason to leave mascots off this list. If people can become connected to fictional characters on television, there is no reason they cannot become attached to a mascot. As demonstrated with the image below, other users respond to Benny in a similar way that they would to other creators. This is not the type of comment you would see with a branded account, but rather a social interaction that is common among online friends and followers. Having an individual, even if it’s a mascot, to respond and connect with makes it much easier to form these parasocial relationships. This is where immersion is important. Although Benny has other social media accounts, none afford him with the immersive experience that TikTok does.

Having people connect with Benny is smart for the Chicago Bulls. Firstly, with the official account showing multiple players on a day-to-day basis, it would be harder for fans to form a parasocial bond. That kind of attachment and identification with the team looks more like fandom than a parasocial relationship. Secondly, the Bulls don’t have to inundate fans of Benny the Bull with highlight clips or sport-specific content. Instead, they just let Benny do his thing, yet still reap the benefits of the Chicago Bulls branding, social media engagement, and potential crossover of new and younger fans. The Benny the Bull TikTok account allows the team to connect with fans at a parasocial level, which is something that’s difficult to do as a sports team.

Final Thoughts

Although Benny the Bull is associated with the Chicago Bulls, the account itself is not as sports-focused as the primary TikTok account of the Bulls, expanding the potential for users not interested in sports to become connected to the character. Mascots have always been used as a form of branding (Vrabel, 2017), and with TikTok offering a new platform for sports organizations to foster existing relationships, promote their brand, and appeal to new fans (Su et al., 2020), mascots have a new and exciting outlet. The dance-focused, sometimes silly TikTok platform, is perfect for characters like Benny the Bull to successfully transition from being obscure relics of the in-stadium sports experience to being integral for continued success among Gen Z and social media sites dedicated to creativity. With sports organizations poised to use TikTok as part of their media strategy, don’t be surprised to see your teams’ mascot dancing along to the newest trend.

Image Credits:

- The Chicago Bull’s Mascot: Benny the Bull

- @bennythebull’s TikTok, 2/15/20

- @bennythebull’s TikTok, 1/14/20

- TikTok users have formed a parasocial relationship with Benny (Author’s screengrab)

Benny the Bull. (n.d.). About Benny. http://iwantbenny.com/about-benny.html

Borrelli, C. (2019, March 30). Benny the Bull has accompanied a mayor to China, topped a Forbes list and been arrested at the Taste of Chicago: And that’s only part of his story. Chicago Tribune. https://www.chicagotribune.com/sports/bulls/ct-spt-bulls-benny-the-bull-history-20190330-story.html

Burke, S. (2020, April 29). Some pros let it go on TikTok: ‘Is this the future?’ The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/29/arts/dance/tiktok-dance-challenges.html

Dinhopl, A., & Gretzel, U. (2015). Changing practices/new technologies: Photos and videos on vacation. In Tussyadiah I., Inversini A. (Eds.), Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2015. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-14343-9_56

Horton, D., & Wohl, R.R. (1956). Mass communication and para-social interaction: Observations on intimacy at a distance. Psychiatry, 19, 215-229. https://doi-org/10.1080/00332747.1956.11023049

Hu, Y., Manikonda, L., & Kambhampati, S. (2014). What we Instagram: A first analysis of Instagram photo content and user types. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, ICWSM 2014 (pp. 595-598). (Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, ICWSM 2014). The AAAI Press. https://www.aaai.org/ocs/index.php/ICWSM/ICWSM14/paper/viewFile/8118/8087

Kim, J., & Song, H. (2016). Celebrity’s self-disclosure on Twitter and parasocial relationships: A mediating role of social presence. Computers in Human Behavior, 62, 570-577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.083

Madu, Z. (2020, February 17). The NBA invited Jalaiah Harmon to perform ‘renegade’ and showed how to address appropriation. SB Nation. https://www.sbnation.com/nba/2020/2/17/21141239/renegade-dance-nba-all-star-game-jalaiah-harmon-cultural-appropriation

Moran, E. (2019, November 29). How The Chicago Bulls’ Benny The Bull inspired a TikTok movement. Front Office Sports. https://frontofficesports.com/benny-the-bull-tiktok/

Nielsen Sports. (n.d.). Nielsen sports 2020 commercial trends. https://nielsensports.com/nielsen-sports-2020-commercial-trends/

Parker, K, & Igielnik, R. (2020). On the cusp of adulthood and facing an uncertain future: What we know about Gen Z so far. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/essay/on-the-cusp-of-adulthood-and-facing-an-uncertain-future-what-we-know-about-gen-z-so-far/

Pegoraro, A. (2017). Sports fandom in the digital world. In P. M. Pederson (Ed.), Routledge Handbook of Sports Communication. Routledge.

Sehl, K. (2020, May 7). 20 important TikTok stats marketers need to know in 2020. Hootsuite. https://blog.hootsuite.com/tiktok-stats/#:~:text=TikTok%20has%20a%20reputation%20for,of%20the%20app’s%20user%20base

Siguencia, L. O., Herman, D., Marzano, G., & Rodak, P. (2017). The role of social media in sports communication management: An analysis of Polish top league teams’ strategy. Procedia Computer Science, 104, 73-80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2017.01.074

Su, Y., Baker, B. J., Doyle, J. P., & Yan, M. (2020). Fan engagement in 15 seconds: Athletes’ relationship marketing during a pandemic via TikTok. International Journal of Sport Communication, 13(3), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsc.2020-0238

Vrabel, J. (2017). Lions and tigers and bears (and zips and banana slugs and purple cows) — oh, my! NCAA Champion Magazine. http://www.ncaa.org/static/champion/mascots/

Wandel, T. L. (2017). Brand anthropomorphism: Collegiate mascots and social media. In R. Garg, R. Chhikara, T. K. Panda, & A. Kataria (Eds.), Driving customer appeal through the use of emotional branding. IGI Global.

Wang, Y., & Zhou, S. (2015). How do sports organizations use social media to build relationships? A content analysis of NBA clubs’ Twitter use. International Journal of Sport Communication, 8(2), 133-148. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsc.2014-0083

Wang, Y. (2020). Humor and camera view on mobile short-form video apps influence user experience and technology-adoption intent, an example of TikTok (DouYin). Computers in Human Behavior, 110, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106373

Waterloo, S. F., Baumgartner, S. E., Peter, J., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2018). Norms of online expressions of emotion: Comparing Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and WhatsApp. New Media & Society, 20(5), 1813–1831. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817707349

Weiss, O. (1996). Media sports as a social substitution pseudosocial relations with sports figures. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 31(1), 109-117. https://doi.org/10.1177/101269029603100106

The only natural option on a platform where dancing flourishes is to employ the mascot, not only because they have a history of dancing, but also because it is a more informal method to communicate with fans than bringing in a professional athlete.