“Stop Treating The Protests Like Coachella”: On the Uses of Sousveillance for Social Justice

Kathy Cacace / University of Texas at Austin

Since late May, the United States has seen a sweeping protest movement against racial injustice spurred by the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade, and other Black citizens by police officers. These protests build on the Black Lives Matter movement that arose after Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Sandra Bland and others were murdered by police and videos documenting events leading up to and including these murders circulated on social media. The recording via cell phone of police violence and the subsequent sharing of these violent videos is a double-edged sword slicing Black Americans both ways. Their circulation may drive awareness in white Americans of the deadly effects of systemic racism, however painfully late that awareness comes, but they do so by inflicting trauma on Black social media users who are, by virtue of their very subjectivity, acutely aware of how the system works.

Technology theorist Lisa Nakamura, whose work on race and technology has been foundational to the field of media studies since the 1980s, spoke on Twitter during the recent protests about the relationship between technology and policing. Early in her career, Nakamura, like many others, hoped that turning the tools of surveillance on unjust institutions like law enforcement might lead to a leveling of power. Instead, it seems that as videos of police brutality proliferate, police violence continues unabated.

This explains why my black and POC students felt more empowered in the eighties than they do now, despite bodycams; there was some hope for fairness and justice, and none now. Why filming police violence has done nothing to stop it | MIT Technology Review https://t.co/nmX2KaPYPi

— Lisa Nakamura (@lnakamur) June 7, 2020

In 2003, Steve Mann, Jason Nolan, and Barry Wellman observed the integration of invisible data-gathering technology into myriad aspects of everyday life in order to collect information on behalf of organizations including, of course, institutions like law enforcement. They suggest that “one way to challenge and problematize both surveillance and acquiescence to it is to resituate these technologies of control on individuals, offering panoptic technologies to help them observe those in authority. We call this inverse panopticon ‘sousveillance,” roughly meant to invoke a sense of watching from below.[1] Their key example of sousveillance is, prescient of the current moment, George Holliday’s videotape of Rodney King’s beating by Los Angeles police officers in 1991.

Mann et al. argue that sousveillance functions through reflectionism, or using technology to hold up a mirror to an organization and asking “do you like what you see?” The difficulty, from recordings of the Birmingham Children’s Crusade in 1963 to recordings of police violence at the 2020 protests, is that law enforcement and the justice system resoundingly respond to that question by insisting: “Nothing to see here, move along.” In a short essay on the failed promise of police body cams linked in Nakamura’s tweet, Ethan Zuckerman synthesizes years of research on increased recording of police interactions and concludes that these films “have worked to bolster ‘reasonable fear’ defense claims as much as they have demonstrated the culpability of police officers.”[2] Such video might be slowed down to reveal someone murdered by police indeed was not armed, was retreating, was still, had their hands in the air. But, played at full speed, those with an investment in maintaining our unjust system of policing can and will see confusion, danger, and split-second decisions that support an officer’s choice to shoot first and ask questions later. Based on the miniscule rates of prosecution for police officers who have killed Black citizens, these recordings of racist police violence by cell phone or bodycam is more likely to exonerate police officers who commit violence than to convict them or even merely get them fired.

Police body cameras in theory fall somewhere between surveillance and sousveillance, in that they are meant to produce a purportedly objective recording of police officers and those with whom they interact. The belief that video can produce an irrefutable record of the truth in fact reenacts some of the earliest hopes about photography as it came to prominence in the nineteenth century. As Rebecca Solnit describes it, in language that fittingly echoes police procedure, photography by the 1850s was considered to be “a piece of evidence from the event itself, a material witness.”[3] Inasmuch as control over body cameras falls to individual officers, who can and do turn them off, they do not function in practice as sousveillance. Likewise, sousveillance of police via cell phone camera has not worked as technology theorists had hoped. Videos shot by witnesses can always be consumed by white supremacy and digested to produce further injustice.

The difficulty with sousveillance as a technology of equality is in the fundamentally inequitable distribution of what I will call non-optical authority, or power that is not derived from images, between the citizen and the state. A bystander may capture clear video of a police officer committing a racist murder, but the state does not get its power solely from images of just policing. That video may circulate through both social and traditional media, thereby changing public opinion toward the officer, department, or institution of policing. But the police are not celebrities; their power does not come from public opinion. At its most effective, that video might a) produce incremental change by persuading viewers to vote for political candidates interested in defunding the police and/or b) become a piece of evidence in a trial whose terms are set by the state. Data shows that district attorneys almost never bring charges against police officers who kill citizens; though more than 1,000 people are killed by police each year, only 110 have been prosecuted since 2005. Police certainly gain some portion of their power from public approval, but it pales in comparison to the deadly authority they derive from state-issued credentials, in the form of a badge, and state-issued tools of enforcement, including weapons. A citizen’s camera might be able to record the state’s bullet, but it cannot deflect it.

All this said, there are two strange angles through which sousveillance seems to be serving a purpose throughout this summer’s sustained Black Lives Matter uprising. The first occurred on Instagram. Shortly after the protests began, the popular Instagram account @influencersinthewild turned its feed away from its usual content—stealthily shot videos of Instagram influencers staging elaborate photographs of themselves in public—and focused in on white influencers staging photos of themselves at protests without meaningfully contributing to the movement.[4] A typical video (since removed), depicted a slim, well-dressed white woman in a floaty black gown and high heels. She is with another fashionable white woman who holds a camera. As a Black Lives Matter protest passes by, she steps into the flow of foot traffic holding a protest sign in one hand while arranging her garment and hair with the other. The short video ends as she assumes a pose for the camera. The caption implores her, or perhaps @influencersinthewild followers, to “stop treating the protests like Coachella” (referring to the California music festival known as much as a place to be seen as it is a place to hear artists perform).

From June 1 through June 7, 2020, @influencersinthewild published ten such user-submitted videos. This manifestation of sousveillance does not turn its camera on the traditional institutions of power, like the police. Instead, this account exposes and undermines people whose power is explicitly optical—that is, accrued through images. It uses shame to dispel power gained through social regard. Not unlike @celebface, an Instagram account that exposes digital editing of beauty photographs by major and microcelebrities on their social media accounts, @influencersinthewild interrupts the seamless presentation of self as product. Theresa M. Senft describes micro-celebrity as “a practice, rather than a person: it’s the presentation of one’s online self as a branded good, with the expectation that others are doing the same. When this presentation involves an intention to monetize, I call that person an influencer.”[5] Crystal Abidin further theorizes the appeal of internet celebrities, a more broadly conceived category than the microinfluencer, and finds that the qualities of exclusivity, exoticism, exceptionalism, and/or everydayness “each corresponds to a specific form of capital that arouse interest and attention, whether positive (i.e. out of admiration or love) or negative (i.e., out of disgust or judgement).”[6]

The white female fashion, beauty, or wellness influencer often sits at the crossroads of exclusivity, exceptionalism, and everydayness, publishing an uninterrupted, impossibly optimized self for direct consumption or as the ambassador for a brand. In its usual function, @influencersinthewild subverts these images by creating a third dimension: by filming from an unanticipated angle, the viewer sees their construction rather than their supposed naturalness. The influencer is no longer a perfect body on a beach during the golden hour. She becomes an awkward spectacle of self-promotion amid the “real” everyday. When these influencers are placed within the context of a social movement for Black lives, the exposure of the construction of a meaningless gesture serves the opposite function: revealing that no work went into the protest, no effort was made to contribute to the cause.

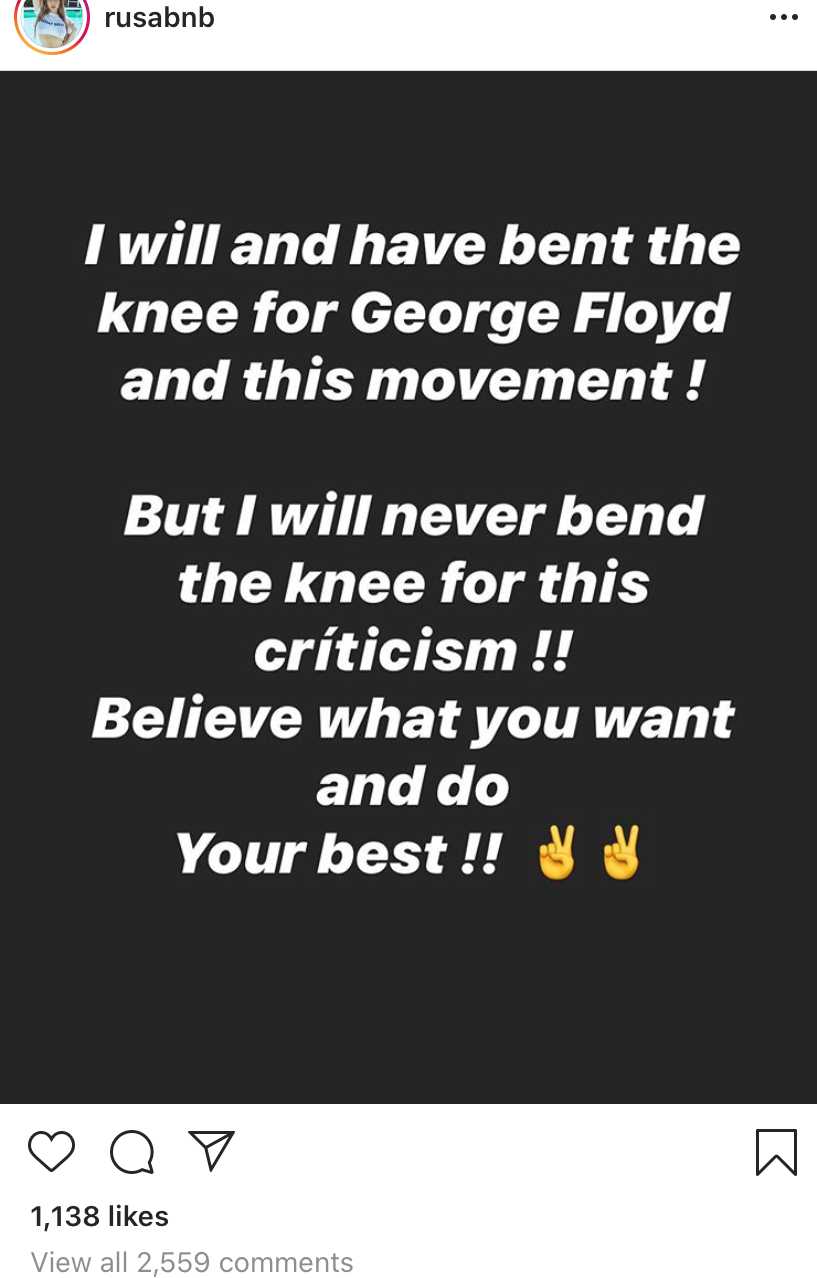

@influencersinthewild creator George Resch, known on Instagram by his pseudonym “Tank Sinatra,” is the director of influencer marketing at BrandFire, an advertising agency in New York. After posting the ten videos exposing untagged, unidentified white influencers using the protests to stage self-branding, Resch found that followers of his account were able to crowdsource both online and offline identities of the offending influencers and heap criticism on them. The woman in the black dress was revealed to be @rusabnb, a model/influencer with more than 200,000 followers. In the following days, she used her account to position herself as the victim of bullying, posting “I will and have bent the knee for George Floyd and this movement! But I will never bend the knee for this criticism!!”

Resch responded first by posting an IGTV video in which he which he admitted that white influencers who “have co-opted the BLM movement in order to get content” are committing “the single most egregious act of cultural appropriation” but ultimately decrying the doxxing of their personal information. “My purpose was to expose the behavior, not the individual,” he explained. Resch then scheduled an Instagram Live interview with @rusabnb, a choice which was met with emphatic backlash. “The fact that you’re having a girl who stood for a photo shoot at a BLM protest as a headliner says a lot about your account,” said one commenter. “We don’t care about her struggle in the aftermath of posting. You shouldn’t be giving a voice to her. She doesn’t deserve one.”[7]

On the live forum, @rusabnb and the woman who had taken her photograph, who appeared to be some sort of handler, chalked their “mistake” up to cultural difference and lack of education, since they have only lived in the U.S. for a little over a year. @rusabnb did not apologize, focusing instead on threats and insults she has received and emphasizing instead that “you never know how people can react, and we never expected something like this,” that “everyone makes mistakes,” that critiquing her action was “detrimental to the movement,” and lamenting that her business is “ruined.” Resch then invited Black critics from among his commenters to join the Instagram live, relying on the free labor of Black social media users to clean up @rusabnb’s damage.

Resch has subsequently scrubbed his platform of any protest-related videos and @rusabnb has turned her account private. While scant evidence of these videos exists online except for Resch’s archived IGTV videos, this episode does demonstrate the effectiveness of sousveilling—through cell phone recordings and by scrutinizing their public-facing data—individuals whose power relies on optical authority. @instagraminthewild users were able to capture and identify a white microcelebrity capitalizing on the racial justice movement, and @rusabnb’s account remains private, her business effectively disrupted.

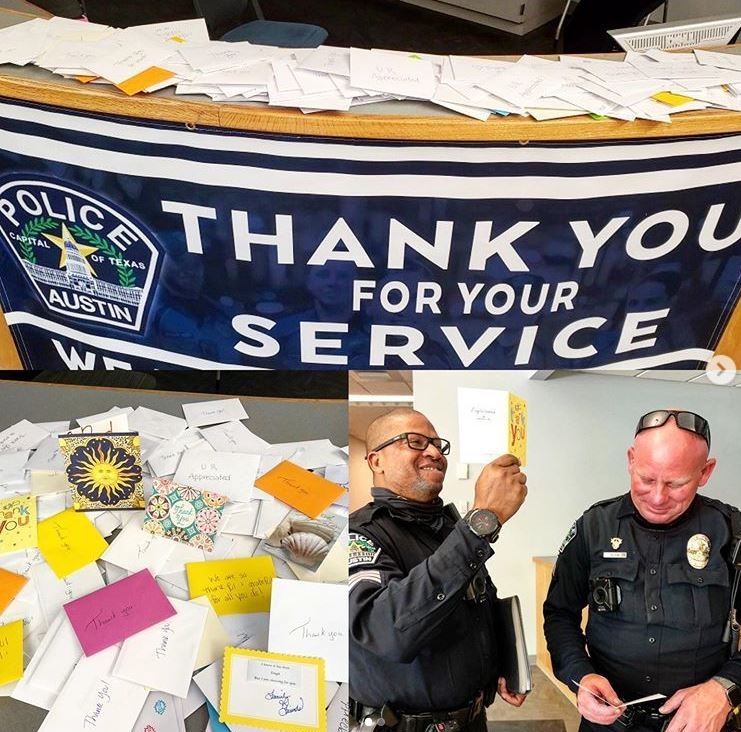

As the doxxing element of the @rusabnb episode demonstrates, sousveillance is as much about understanding the data online images contain as it is about producing counterimages. I would like to propose, then, an expanded understanding of sousveillance to include not simply “reflecting” authority, but by submitting the data produced by authority to the same sort of scrutiny to which our data is subjected. My second example of effective sousveillance emerged in Austin, Texas, when the Austin Police Department published an image of a pile of supposed thank you notes received by the department during the June protests.

Their Twitter/Instagram post was intended to work on the plane of images to rehabilitate the public perception of the APD after seriously injuring a number of protesters with so-called “less lethal” rounds, including shooting a pregnant Black woman in the abdomen. Social media users were quick to notice that all the thank you notes were written in the same handwriting and had no stamps on them. When asked by the press who sent the cards, the department was unable to come up with a coherent response, citing first a “kindergarten class” (though no Austin schools are currently in session) and later “a group of kindergarteners.” Further reporting by Texas Monthly procured images of many of the cards through an open records request, which only compounded the suspicious appearance of these artifacts. Comedians like Nathan Fielder quickly seized the opportunity to mock such an obvious stunt.

I know how it feels! I can’t express how grateful I am to serve my fans. I’m overwhelmed by how many people took the time to make my day a little brighter. https://t.co/rFMkVlt4ae pic.twitter.com/KjIw2xa7zl

— nathan fielder (@nathanfielder) June 10, 2020

If the intention of the APD was to minimize civil unrest and convince social media users that they enjoy broad public favor, subjecting their image to civilian scrutiny had the opposite effect. Sousveillance here is not about producing a counterimage—say, photographing a police officer churning out a hundred phony thank you notes—but instead in recognizing the information embedded within images the APD has produced of itself to gain optical authority. Other examples of this expanded notion of sousveillance might include using police promotional images to associate violent officers with names, badge numbers, or other data by which they might be held accountable for crimes against citizens. This would approximate the sort of inspection that facial-recognition technology applies to images of protestors and subject police images to it.

Mann et al. concede that widespread sousveillance may not be an “act of liberation,” but instead “only serve the ends of the existing power structure” by “fostering broad accessibility of monitoring and ubiquitous data collection.”[8] My argument here is not that sousveillance should be as ubiquitous as surveillance. Many during the recent uprisings have in fact cautioned against citizens widely documenting the protests on social media because such images can be used far more easily by police than by fellow citizens, and resistance may best be accomplished in these situations through other means. Rather, I submit that sousveillance should be understood as a tactic to be applied most forcefully where white supremacy and other forms of oppression seek to garner power through images—and where that power can most effectively be crushed.

Image Credits:

- Instagram model/influencer @rusabnb stages a photograph during a Black Lives Matter protest. This image has since been deleted from @influencersinthewild.

- @Lnakamur’s post from June 7, 2020.

- Police body cameras can be thwarted by officers who turn them off or hide their badge numbers.

- One of @rusabnb’s responses to criticism for using a Black Lives Matter protest to create content. @rusabnb has since made her account private.

- @rusabnb tearfully talks to @influencersinthewild, emphasizing that “everyone makes mistakes.” This video still is from the @influencersinthewild live forum on the protests, now archived on that account’s IGTV section.

- The original image posted by the Austin Police Department on June 6, 2020.

- @NathanFielder’s post from June 9, 2020.

- Steve Mann, Jason Nolan, and Barry Wellman, “Sousveillance: Inventing and Using Wearable Computing Devices for Data Collection in Surveillance Environments,” Surveillance and Society 1, no. 3: 332. [↩]

- Ethan Zuckerman, “Why filming police violence has done nothing to stop it,” MIT Technology Review, June 3, 2020, https://www.technologyreview.com/2020/06/03/1002587/sousveillance-george-floyd-police-body-cams/ [↩]

- Rebecca Solnit, River of Shadows (New York: Penguin Books, 2003): 17. [↩]

- All videos have since been removed by the account owner. Descriptions have been constructed from the author’s screenshots, contemporaneous transcriptions, and where necessary, memory. [↩]

- Teresa M. Senft, “Fame, Shame, Remorse, Authenticity: A Prologue,” in Microcelebrity Around the Globe, ed. Crystal Abidin and Megan Lindsay Brown (Bingley: Emerald Publishing, 2018): xiv. [↩]

- Crystal Abidin, Internet Celebrity: Understanding Fame Online (Bingley: Emerald Publishing, 2018): 19. [↩]

- Author’s transcription of a screenshotted comment on a since-deleted post. [↩]

- Mann et al, “Sousveillance,” 347. [↩]